Astronomy:Maya calendar

|

| Maya civilization |

|---|

| History |

| Preclassic Maya |

| Classic Maya collapse |

| Spanish conquest of the Maya |

The Maya calendar is a system of calendars used in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and in many modern communities in the Guatemalan highlands,[1] Veracruz, Oaxaca and Chiapas, Mexico.[2]

The essentials of the Maya calendar are based upon a system which had been in common use throughout the region, dating back to at least the 5th century BC. It shares many aspects with calendars employed by other earlier Mesoamerican civilizations, such as the Zapotec and Olmec and contemporary or later ones such as the Mixtec and Aztec calendars.[3]

By the Maya mythological tradition, as documented in Colonial Yucatec accounts and reconstructed from Late Classic and Postclassic inscriptions, the deity Itzamna is frequently credited with bringing the knowledge of the calendrical system to the ancestral Maya, along with writing in general and other foundational aspects of Mayan culture.[4]

Overview

The Maya calendar consists of several cycles or counts of different lengths. The 260-day count is known to scholars as the Tzolkin, or Tzolkʼin.[5] The Tzolkin was combined with a 365-day vague solar year known as the Haabʼ to form a synchronized cycle lasting for 52 Haabʼ called the Calendar Round. The Calendar Round is still in use by many groups in the Guatemalan highlands.[6]

A different calendar was used to track longer periods of time and for the inscription of calendar dates (i.e., identifying when one event occurred in relation to others). This is the Long Count. It is a count of days since a mythological starting-point.[7] According to the correlation between the Long Count and Western calendars accepted by the great majority of Maya researchers (known as the Goodman-Martinez-Thompson, or GMT, correlation), this starting-point is equivalent to August 11, 3114 BC in the proleptic Gregorian calendar or September 6, in the Julian calendar (−3113 astronomical). The GMT correlation was chosen by John Eric Sydney Thompson in 1935 on the basis of earlier correlations by Joseph Goodman in 1905 (August 11), Juan Martínez Hernández in 1926 (August 12) and Thompson himself in 1927 (August 13).[8] By its linear nature, the Long Count was capable of being extended to refer to any date far into the past or future. This calendar involved the use of a positional notation system, in which each position signified an increasing multiple of the number of days. The Maya numeral system was essentially vigesimal (i.e., base-20) and each unit of a given position represented 20 times the unit of the position which preceded it. An important exception was made for the second-order place value, which instead represented 18 × 20, or 360 days, more closely approximating the solar year than would 20 × 20 = 400 days. The cycles of the Long Count are independent of the solar year.

Many Maya Long Count inscriptions contain a supplementary series, which provides information on the lunar phase, number of the current lunation in a series of six and which of the nine Lords of the Night rules.

Less-prevalent or poorly understood cycles, combinations and calendar progressions were also tracked. An 819-day Count is attested in a few inscriptions. Repeating sets of 9 days (see below "Nine lords of the night")[9] associated with different groups of deities, animals and other significant concepts are also known.

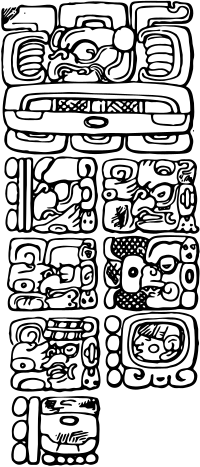

Tzolkʼin

The tzolkʼin (in modern Maya orthography; also commonly written tzolkin) is the name commonly employed by Mayanist researchers for the Maya Sacred Round or 260-day calendar. The word tzolkʼin is a neologism coined in Yucatec Maya, to mean "count of days" (Coe 1992). The various names of this calendar as used by precolumbian Maya people are still debated by scholars. The Aztec calendar equivalent was called Tōnalpōhualli, in the Nahuatl language.

The tzolkʼin calendar combines twenty day names with the thirteen day numbers to produce 260 unique days. It is used to determine the time of religious and ceremonial events and for divination. Each successive day is numbered from 1 up to 13 and then starting again at 1. Separately from this, every day is given a name in sequence from a list of 20 day names:

| Seq. Num. 1 |

Day Name 2 |

Glyph example 3 |

16th-c. Yucatec 4 |

K'iche' | Reconstructed Classic Maya 5 |

Seq. Num. 1 |

Day Name 2 |

Glyph example 3 |

16th-c. Yucatec 4 |

Quiché | Reconstructed Classic Maya 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Imix | 50px | Imix | Imox | Imix (?) / Haʼ (?) | 11 | Chuwen | 50px | Chuen | Bʼatzʼ | (unknown) | |

| 02 | Ikʼ | 50px | Ik | Iqʼ | Ikʼ | 12 | Ebʼ | 50px | Eb | Eʼ | (unknown) | |

| 03 | Akʼbʼal | 50px | Akbal | Aqʼabʼal | Akʼbʼal (?) | 13 | Bʼen | 50px | Ben | Aj | C'klab[clarification needed] | |

| 04 | Kʼan | 50px | Kan | Kʼat | Kʼan (?) | 14 | Ix | 50px | Ix | Iʼx, Balam | Hix (?) | |

| 05 | Chikchan | 50px | Chicchan | Kan | (unknown) | 15 | Men | 50px | Men | Tzikin | Men (?)[10] | |

| 06 | Kimi | 50px | Cimi | Kame | Cham (?) | 16 | Kʼibʼ | 50px | Cib | Ajmaq | (unknown) | |

| 07 | Manikʼ | 50px | Manik | Kej | Manichʼ (?) | 17 | Kabʼan | 50px | Caban | Noʼj | Chabʼ (?) | |

| 08 | Lamat | 50px | Lamat | Qʼanil | Ekʼ (?) | 18 | Etzʼnabʼ | 50px | Etznab | Tijax | (unknown) | |

| 09 | Muluk | 50px | Muluc | Toj | (unknown) | 19 | Kawak | 50px | Cauac | Kawoq | (unknown) | |

| 10 | Ok | 50px | Oc | Tzʼiʼ | (unknown) | 20 | Ajaw | 50px | Ahau | Ajpu | Ajaw | |

NOTES:

| ||||||||||||

Some systems started the count with 1 Imix, followed by 2 Ikʼ, 3 Akʼbʼal, etc. up to 13 Bʼen. The day numbers then start again at 1 while the named-day sequence continues onwards, so the next days in the sequence are 1 Ix, 2 Men, 3 Kʼibʼ, 4 Kabʼan, 5 Etzʼnabʼ, 6 Kawak and 7 Ajaw. With all twenty named days used, these now began to repeat the cycle while the number sequence continues, so the next day after 7 Ajaw is 8 Imix. The repetition of these interlocking 13- and 20-day cycles therefore takes 260 days to complete (that is, for every possible combination of number/named day to occur once).

The earliest known inscription with a Tzolkʼin is an Olmec earspool with 2 Ahau 3 Ceh - 6.3.10.9.0, September 2, -678 (Julian astronomical).[12]

Haabʼ

| Seq. Num. |

Yucatec name |

Hieroglyph |

Classic Period

glyph sign |

Meaning of glyph [14] |

Reconstructed Classic Maya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pop | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | k'anjalaw | |

| 2 | Woʼ | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | ik'at | |

| 3 | Sip | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | chakat | |

| 4 | Sotzʼ | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | bat | sotz' |

| 5 | Sek | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | kaseew | |

| 6 | Xul | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | chikin | |

| 7 | Yaxkʼin | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | yaxk'in | |

| 8 | Mol | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | mol | |

| 9 | Chʼen | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | black[15] | ik'siho'm |

| 10 | Yax | Template:Haab20 | yaxsiho'm | ||

| 11 | Sak | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | white[15] | saksiho'm |

| 12 | Keh | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | red[15] | chaksiho'm |

| 13 | Mak | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | mak | |

| 14 | Kʼankʼin | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | uniiw | |

| 15 | Muwan | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | muwaan | |

| 16 | Pax | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | paxiil | |

| 17 | Kʼayab | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | k'anasiiy | |

| 18 | Kumkʼu | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | ohl | |

| 19 | Wayebʼ | Template:Haab20 | 71x71px | five unlucky days | wayhaab |

The Haabʼ was made up of eighteen months of twenty days each plus a period of five days ("nameless days") at the end of the year known as Wayeb' (or Uayeb in 16th-century orthography). The five days of Wayebʼ were thought to be a dangerous time. Foster (2002) writes, "During Wayeb, portals between the mortal realm and the Underworld dissolved. No boundaries prevented the ill-intending deities from causing disasters." To ward off these evil spirits, the Maya had customs and rituals they practiced during Wayebʼ. For example, people avoided leaving their houses and washing or combing their hair. Bricker (1982) estimates that the Haabʼ was first used around 550 BC with a starting point of the winter solstice.[16]

The Haabʼ month names are known today by their corresponding names in colonial-era Yukatek Maya, as transcribed by 16th-century sources (in particular, Diego de Landa and books such as the Chilam Balam of Chumayel). Phonemic analyses of Haabʼ glyph names in pre-Columbian Maya inscriptions have demonstrated that the names for these twenty-day periods varied considerably from region to region and from period to period, reflecting differences in the base language(s) and usage in the Classic and Postclassic eras predating their recording by Spanish sources.[17]

Each day in the Haabʼ calendar was identified by a day number in the month followed by the name of the month. Day numbers began with a glyph translated as the "seating of" a named month, which is usually regarded as day 0 of that month, although a minority treat it as day 20 of the month preceding the named month. In the latter case, the seating of Pop is day 5 of Wayebʼ. For the majority, the first day of the year was 0 Pop (the seating of Pop). This was followed by 1 Pop, 2 Pop as far as 19 Pop then 0 Wo, 1 Wo and so on.

Because the Haabʼ had 365 days and the tropical year is 365.2422 days, the days of the Haabʼ did not coincide with the tropical year.

Calendar Round

A Calendar Round date is a date that gives both the Tzolkʼin and Haabʼ. This date will repeat after 52 Haabʼ years or 18,980 days, a Calendar Round. For example, the current creation started on 4 Ahau 8 Kumkʼu. When this date recurs it is known as a Calendar Round completion.

Arithmetically, the duration of the Calendar Round is the least common multiple of 260 and 365; 18,980 is 73 × 260 Tzolkʼin days and 52 × 365 Haabʼ days.[18]

Not every possible combination of Tzolkʼin and Haabʼ can occur. For Tzolkʼin days Imix, Kimi, Chuwen and Kibʼ, the Haabʼ day can only be 4, 9, 14 or 19; for Ikʼ, Manikʼ, Ebʼ and Kabʼan, the Haabʼ day can only be 0, 5, 10 or 15; for Akbʼalʼ, Lamat, Bʼen and Etzʼnabʼ, the Haabʼ day can only be 1, 6, 11 or 16; for Kʼan, Muluk, Ix and Kawak, the Haabʼ day can only be 2, 7, 12 or 17; and for Chikchan, Ok, Men and Ajaw, the Haabʼ day can only be 3, 8, 13 or 18.[19]

Year Bearer

A "Year Bearer" is a Tzolkʼin day name that occurs on 0 Pop, the first day of the Haabʼ. Since there are 20 Tzolkʼin day names, 365 days in the Haabʼ, and the remainder of 365 divided by 20 is 5 (365 = 18×20 + 5), the Tzolkʼin day name for each successive 0 Pop will be 5 later in the cycle of Tzolk'in day names. Similarly, since there are 13 Tzolk'in day numbers, and the remainder of 365 divided by 13 is 1 (365 = 28×13 + 1), the Tzolk'in day number for each successive 0 Pop will be 1 greater than before. As such, the sequence of Tzolk'in dates corresponding to the Haab' date 0 Pop are as follows:

- 1 Ikʼ

- 2 Manikʼ

- 3 Ebʼ

- 4 Kabʼan

- 5 Ikʼ

- ...

- 12 Kab'an

- 13 Ik'

- 1 Manik'

- ...

Thus, the Year Bearers are the four Tzolkʼin day names that appear in this sequence: Ik', Manik', Eb', and Kab'an.

"Year Bearer" literally translates a Mayan concept.[20] Its importance resides in two facts. For one, the four years headed by the Year Bearers are named after them and share their characteristics; therefore, they also have their own prognostications and patron deities.[21] Moreover, since the Year Bearers are geographically identified with boundary markers or mountains, they help define the local community.[22]

The classic system of Year Bearers described above is found at Tikal and in the Dresden Codex. During the Late Classic period a different set of Year Bearers was in use in Campeche. In this system, the Year Bearers were the Tzolkʼin that coincided with 1 Pop. These were Akʼbʼal, Lamat, Bʼen and Edznab. During the Post-Classic period in Yucatán a third system was in use. In this system the Year Bearers were the days that coincided with 2 Pop: Kʼan, Muluc, Ix and Kawak. This system is found in the Chronicle of Oxkutzcab. In addition, just before the Spanish conquest in Mayapan the Maya began to number the days of the Haabʼ from 1 to 20. In this system the Year Bearers are the same as in the 1 Pop – Campeche system. The Classic Year Bearer system is still in use in the Guatemalan highlands[23] and in Veracruz, Oaxaca and Chiapas, Mexico.[24]

Long Count

Since Calendar Round dates repeat every 18,980 days, approximately 52 solar years, the cycle repeats roughly once each lifetime, so a more refined method of dating was needed if history was to be recorded accurately. To specify dates over periods longer than 52 years, Mesoamericans used the Long Count calendar.

The Maya name for a day was kʼin. Twenty of these kʼins are known as a winal or uinal. Eighteen winals make one tun. Twenty tuns are known as a kʼatun. Twenty kʼatuns make a bʼakʼtun.

The Long Count calendar identifies a date by counting the number of days from the Mayan creation date 4 Ahaw, 8 Kumkʼu (August 11, 3114 BC in the proleptic Gregorian calendar or September 6 in the Julian calendar -3113 astronomical dating). But instead of using a base-10 (decimal) scheme, the Long Count days were tallied in a modified base-20 scheme. Thus 0.0.0.1.5 is equal to 25 and 0.0.0.2.0 is equal to 40. As the winal unit resets after only counting to 18, the Long Count consistently uses base-20 only if the tun is considered the primary unit of measurement, not the kʼin; with the kʼin and winal units being the number of days in the tun. The Long Count 0.0.1.0.0 represents 360 days, rather than the 400 in a purely base-20 (vigesimal) count.

There are also four rarely used higher-order cycles: piktun, kalabtun, kʼinchiltun, and alautun.

Since the Long Count dates are unambiguous, the Long Count was particularly well suited to use on monuments. The monumental inscriptions would not only include the 5 digits of the Long Count, but would also include the two tzolkʼin characters followed by the two haabʼ characters.

Misinterpretation of the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar was the basis for a popular belief that a cataclysm would take place on December 21, 2012. December 21, 2012 was simply the day that the calendar went to the next bʼakʼtun, at Long Count 13.0.0.0.0. The date of the start of the next b'ak'tun (Long Count 14.0.0.0.0) is March 26, 2407. The date of the start of the next piktun (a complete series of 20 bʼakʼtuns), at Long Count 1.0.0.0.0.0, is October 13, 4772.

| Long Count unit |

Long Count period |

Days | Approximate Solar Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Kʼin | 1 | ||

| 1 Winal | 20 Kʼin | 20 | |

| 1 Tun | 18 Winal | 360 | 1 |

| 1 Kʼatun | 20 Tun | 7,200 | 20 |

| 1 Bʼakʼtun | 20 Kʼatun | 144,000 | 394 |

| 1 Piktun | 20 Bʼakʼtun | 2,880,000 | 7,885 |

| 1 Kalabtun | 20 Piktun | 57,600,000 | 157,704 |

| 1 Kʼinchiltun | 20 Kalabtun | 1,152,000,000 | 3,154,071 |

| 1 Alautun | 20 Kʼinchiltun | 23,040,000,000 | 63,081,429 |

| 1 Hablatun | 20 Alautun | 460,800,000,000 | 1,261,628,585 |

Supplementary Series

Many Classic period inscriptions include a series of glyphs known as the Supplementary Series. The operation of this series was largely worked out by John E. Teeple. The Supplementary Series most commonly consists of the following elements:

Lords of the Night

Each night was ruled by one of the nine lords of the underworld. This nine-day cycle was usually written as two glyphs: a glyph that referred to the Nine Lords as a group, followed by a glyph for the lord that would rule the next night.

Lunar Series

A lunar series generally is written as five glyphs that provide information about the current lunation, the number of the lunation in a series of six, the current ruling lunar deity and the length of the current lunation.

Moon age

The Maya counted the number of days in the current lunation. They used two systems for the zero date of the lunar cycle: either the first night they could see the thin crescent moon or the first morning when they could not see the waning moon.[25] The age of the moon was depicted by a set of glyphs that mayanists coined glyphs D and E:

- A new moon glyph was used for day zero in the lunar cycle.

- D glyphs were used for lunar ages for days 1 through 19, with the number of days that had passed from the new moon.

- For lunar ages 20 to 30, an E glyph was used, with the number of days from 20.

Count of Lunations

The Maya counted the lunations. This cycle appears in the lunar series as two glyphs that modern scholars call the 'C' and 'X' glyphs. The C glyph could be prefixed with a number indicating the lunation. No prefixing number meant one, whereas the numbers two through six indicated the other lunations.[26][27] There was also a part of the C glyph that indicated where this fell in a larger cycle of 18 lunations. Accompanying the C glyph was the 'X' glyph that showed a similar pattern of 18 lunations.[28][29]

Lunation length

The present era lunar synodic period is about 29.5305877 mean solar days or about 29 days 12 hours 44 minutes and 2+7/9 seconds. As a whole number, the number of days per lunation will be either 29 or 30 days, with the 30-day intervals necessarily occurring slightly more frequently than the 29-day intervals. The Maya wrote whether the lunar month was 29 or 30 days as two glyphs: a glyph for lunation length followed by either a glyph made up of a moon glyph over a bundle with a suffix of 9 for a 29-day lunation or a moon glyph with a suffix of 10 for a 30-day lunation. Since the Maya didn't use fractions, lunations were approximated by using the formula that there were 149 lunations completed in 4400 days, which yielded a rather short mean month of exactly 4400/149 = 29+79/149 days = 29 days 12 hours 43 minutes and 29+59/149 seconds, or about 29.5302 days.[30]

819-day count

Some Mayan monuments include glyphs that record an 819-day count[31] in their Initial Series. These can also be found in the Dresden codex.[32] This is described in Thompson.[33] More examples of this can be found in Kelley.[34] Each group of 819 days was associated with one of four colors and the cardinal direction with which it was associated – black corresponded to west, red to east, white to north and yellow to south.

The 819-day count can be described several ways: Most of these are referred to using a "Y" glyph and a number. Many also have a glyph for Kʼawill – the god with a smoking mirror in his head. Kʼawill has been suggested as having a link to Jupiter.[35] In the Dresden codex almanac 59 there are Chaacs of the four colors. The accompanying texts begin with a directional glyph and a verb for 819-day-count phrases. Anderson[36] provides a detailed description of the 819-day count.

Synodic periods of the classical planets

Moon: 1 x 819 + 8 days = 28 (synodic 29.53 d) "28 months" Moon: 4 x 819 + 2 days = 111 (synodic 29.53 d) "111 months" Moon: 15 x 819 + 0.3 days = 416 (synodic 29.53 d) "416 months"

Draconic: 31 x 819 days = 933 (draconic 27.21 d) "nodal months"

Mercury: 1 x 819 + 8 days = 7 (synodic 115.88 d) Mercury: 15 x 819 + 2 days = 106 (synodic 115.88 d)

Venus: 5 x 819 + 8 days = 7 (synodic 583.9 d)

Sun: 4 x 819 + 11 days = 9 (synodic 365.24 d) "9 years" Sun: 33 x 819 + 1 days = 74 (synodic 365.24 d) "74 years"

Mars: 20 x 819 + 2 days = 21 (synodic 779.9 d)

Jupiter: 1 x 819 + 21 days = 2 (synodic 398.88 d) Jupiter: 19 x 819 + 5 days = 39 (synodic 398.88 d)

Saturn: 6 x 819 - 1 days = 13 (synod 378.09 d)

Short count

During the late Classic period the Maya began to use an abbreviated short count instead of the Long Count. An example of this can be found on altar 14 at Tikal.[38] In the kingdoms of Postclassic Yucatán, the Short Count was used instead of the Long Count. The cyclical Short Count is a count of 13 kʼatuns (or 260 tuns), in which each kʼatun was named after its concluding day, Ahau ('Lord'). 1 Imix was selected as the recurrent 'first day' of the cycle, corresponding to 1 Cipactli in the Aztec day count. The cycle was counted from katun 11 Ahau to katun 13 Ahau. Since a katun is 20 × 360 = 7200 days long, and the remainder of 7200 divided by 13 is 11 (7200 = 553×13 + 11), the day number of the concluding day of each successive katun is 9 greater than before (wrapping around at 13, since only 13 day numbers are used). That is, starting with the katun that begins with 1 Imix, the sequence of concluding day numbers is 11, 9, 7, 5, 3, 1, 12, 10, 8, 6, 4, 2, 13, 11, ..., all named Ahau. The concluding day 13 Ahau was followed by the re-entering first day 1 Imix. This is the system as found in the colonial Books of Chilam Balam. In characteristic Mesoamerican fashion, these books project the cycle onto the landscape, with 13 Ahauob 'Lordships' dividing the land of Yucatán into 13 'kingdoms'.[39]

See also

- 2012 phenomenon

- Maya religion

- Mayanism

- Tres Zapotes#Stela C

- Maya Astronomy

- Aztec calendar

Notes

- ↑ Tedlock, Barbara, Time and the Highland Maya Revised edition (1992 Page 1) "Scores of indigenous Guatemalan communities, principally those speaking the Mayan languages known as Ixil, Mam, Pokomchí and Quiché, keep the 260-day cycle and (in many cases) the ancient solar cycle as well (chapter 4)."

- ↑ Miles, Susanna W, "An Analysis of the Modern Middle American Calendars: A Study in Conservation." In Acculturation in the Americas. Edited by Sol Tax, p. 273. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952.

- ↑ "Maya Calendar Origins: Monuments, Mythistory, and the Materialization of Time". https://www.questia.com/read/119342989.

- ↑ See entry on Itzamna, in Miller and Taube (1993), pp.99–100.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (1988). Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala: Documento de referencia para la pronunciación de los nuevos alfabetos oficiales. Guatemala City: Instituto Indigenista Nacional. For details and notes on adoption among the Mayanist community, see Kettunen & Helmke (2020), p. 7.

- ↑ Tedlock (1992), p. 1

- ↑ "Mythological" in the sense that when the Long Count was first devised sometime in the Mid- to Late Preclassic, long after this date; see e.g. Miller and Taube (1993, p. 50).

- ↑ Voss (2006, p. 138)

- ↑ See separate brief Wikipedia article Lords of the Night

- ↑ Stuart, David (2024-04-19). "Day Sign Notes: Men / Tz'ikin". https://mayadecipherment.com/2024/04/19/day-sign-notes-men/.

- ↑ Classic-era reconstructions are as per Kettunen and Helmke (2020), pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Edmonson, Munro S. (1988). The Book of the Year MIDDLE AMERICAN CALENDRICAL SYSTEMS. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-87480-288-1.

- ↑ Kettunen and Helmke (2020), pp. 58–59

- ↑ These names come from de Landa's description of the calendar and they are commonly used by Mayanists, but the Classic Maya did not use these actual names for the day signs. The original names are unknown. See Coe, Michael D.; Mark L Van Stone (2005). Reading the Maya Glyphs. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-500-28553-4. https://archive.org/details/readingmayaglyph0000coem/page/43.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCoeVanstone43 - ↑ Zero Pop actually fell on the same day as the solstice on 12/27/−575, 12/27/−574, 12/27/−573 and 12/26/−572 (astronomical year numbering, Universal Time), if you don't account for the fact that the Maya region is in roughly time zone UT−6. See IMCCE seasons.

- ↑ Boot (2002), pp. 111–114.

- ↑ For further details, see Thompson 1966: 123–124

- ↑ Kettunen and Helmke (2020), p. 51

- ↑ Thompson 1966: 124

- ↑ For a thorough treatment of the Year Bearers, see Tedlock 1992: 89–90; 99–104 and Thompson 1966

- ↑ See Coe 1965

- ↑ Tedlock 1992: 92

- ↑ Miles, Susanna W, "An Analysis of the Modern Middle American Calendars: A Study in Conservation." In Acculturation in the Americas. Edited by Sol Tax, pp. 273–84. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952.

- ↑ Thompson, J. Eric S. Maya Hieroglyphic Writing, 1950 Page 236

- ↑ Teeple 1931:53

- ↑ Thompson Maya Hieroglyphic Writing 1950:240

- ↑ Linden 1996:343–356.

- ↑ Schele, Grube, Fahsen 1992

- ↑ Teeple 1931:67

- ↑ "The Mayan mystic 819-day calendar" (in English). Mexican Routes. 2024-12-26. https://mexicanroutes.com/the-mayan-mystic-819-day-calendar/. Retrieved 27 Dec 2024.

- ↑ Grofe, Michael John 2007 The Serpent Series: Precession in the Maya Dresden Codex page 55 p. 206

- ↑ Maya Hieroglyphic Writing 1971 pp. 212–217

- ↑ Decipherment of Maya Script, David Kelley 1973 pp. 56–57

- ↑ Star Gods of the Maya Susan Milbrath 1999, University of Texas Press

- ↑ "Lloyd B. Anderson The Mayan 819-day Count and the "Y" Glyph: A Probable association with Jupiter". Traditional High Cultures Home Page. http://www.traditionalhighcultures.org/819-Day-Count_&_Y_Glyph.html.

- ↑ 2023, John H. Linden, Victoria R. Bricker, The Maya 819-Day Count and Planetary Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536122000323

- ↑ Coe, William R. 'TIKAL a handbook of the ancient Maya Ruins' The University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa. 1967 p. 114

- ↑ Roys 1967: 132, 184–185

References

- Aveni, Anthony F. (2001). Skywatchers (originally published as: Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico [1980], revised and updated ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70504-2. OCLC 45195586.

- Boot, Erik (2002). A Preliminary Classic Maya-English/English-Classic Maya Vocabulary of Hieroglyphic Readings. Mesoweb. http://www.mesoweb.com/resources/vocabulary/Vocabulary.pdf. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- Bricker, Victoria R. (February 1982). "The Origin of the Maya Solar Calendar". Current Anthropology (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, sponsored by Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research) 23 (1): 101–103. doi:10.1086/202782. ISSN 0011-3204. OCLC 62217742.

- Chambers, David Wade (1965). "Did the Maya Know the Metonic Cycle". Isis 56 (3): 348–351. doi:10.1086/350004.

- Coe, Michael D. (1965). "A Model of Ancient Maya Community Structure in the Maya Lowlands". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 21. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.21.2.3629386.

- Coe, Michael D. (1987). The Maya (4th revised ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27455-X. OCLC 15895415.

- Coe, Michael D. (1992). Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05061-9. OCLC 26605966. https://archive.org/details/breakingmayacode00coem_0.

- Foster, Lynn V. (2002). Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. with Foreword by Peter Mathews. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-4148-2. OCLC 50676955.

- Ivanoff, Pierre (1971). Mayan Enigma: The Search for a Lost Civilization. Elaine P. Halperin (trans.) (translation of Découvertes chez les Mayas, English ed.). New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 0-440-05528-8. OCLC 150172.

- Jones, Christopher (1984). Deciphering Maya Hieroglyphs. Carl P. Beetz (illus.) (prepared for Weekend Workshop April 7 and 8, 1984, 2nd ed.). Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. OCLC 11641566.

- Kettunen, Harri; Christophe Helmke (2020). Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs: 17th edition. Couvin, Belgium: Wayeb. https://wayeb.org//download/Kettunen_Helmke_2020_Introduction_to_Maya_Hieroglyphs_17th_ed.pdf. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- Linden, John H. (1996). The Deity Head Variants of the C Glyph. The Eight Palenque Round Table, 1993. pp. 343–356.

- MacDonald, G. Jeffrey (27 March 2007). "Does Maya calendar predict 2012 apocalypse?". USA Today (McLean, VA: Gannett Company). ISSN 0734-7456. https://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/2007-03-27-maya-2012_N.htm.

- Milbrath, Susan (1999). Star Gods of the Maya: Astronomy in Art, Folklore, and Calendars. The Linda Schele series in Maya and pre-Columbian studies. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-75225-3. OCLC 40848420.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317. https://archive.org/details/godssymbolsofa00mill.

- Rice, Prudence M., Maya Calendar Origins: Monuments, Mythistory, and the Materialization of Time (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007) .

- Robinson, Andrew (2000). The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs and Pictograms. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28156-4. OCLC 59432784. https://archive.org/details/storyofwriting0000robi.

- Roys, Ralph L. (1967). The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Schele, Linda; David Freidel (1992). A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (originally published New York: Morrow, 1990, pbk reprint ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-688-11204-8. OCLC 145324300. https://archive.org/details/forestofkingsunt0034sche.

- Schele, Linda; Nickolai Grube; Federico Fahsen (October 1992). "The Lunar Series in Classic Maya Inscriptions: New Observation and Interpretations". Texas Notes on Precolumbian Art, Writing, and Culture (29).

- Taub, Ben (2023-04-19). "We Finally Know How The Maya Calendar Matches Up With The Planets". https://iflscience.com/we-finally-know-how-the-maya-calendar-matches-up-with-the-planets-68528.

- Tedlock, Barbara (1992). Time and the Highland Maya (rev. ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-0577-6. OCLC 7653289.

- Teeple, John E. (November 1931). "Maya Astronomy". Contributions to American Archaeology. I (Pub. 403 ed.). Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. pp. 29–116. http://www.mesoweb.com/publications/CAA/CAA02.pdf.

- Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. with commentary based on the ancient knowledge of the modern Quiché Maya. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1985. ISBN 0-671-45241-X. OCLC 11467786.

- Thomas, Cyrus (1897). "Day Symbols of the Maya Year". in J. W. Powell. Sixteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1894–1895 (EBook online reproduction). Washington DC: Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution; U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 199–266. OCLC 14963920. http://www.gutenberg.org:80/etext/18973.

- Thompson, J. Eric S. (1971). Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: An Introduction, 3rd Edition. Civilization of the American Indian Series, No. 56 (3rd ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0447-3. OCLC 275252.

- Landa's Relación de las cosas de Yucatán: a translation. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University vol. 18. Charles P. Bowditch and Ralph L. Roys (additional trans.) (translation of Diego de Landa's Relación de las cosas de Yucatán [original c. 1566], with notes, commentary, and appendices incorporating translated excerpts of works by Gaspar Antonio Chi, Tomás López Medel, Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, and Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. English ed.). Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. 1941. OCLC 625693.

- Voss, Alexander (2006). "Astronomy and Mathematics". in Nikolai Grube. Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne, Germany: Könemann. pp. 130–143. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maya calendar. |

- Day Symbols of the Maya Year at Project Gutenberg 1897 text by Cyrus Thomas

- The Mayan Calendar: what is it and how does it work? // Calendarr

- date converter at FAMSI This converter uses the Julian/Gregorian calendar and includes the 819 day cycle and lunar age.

- Interactive Maya Calendars

|