Equivalence class

In mathematics, when the elements of some set have a notion of equivalence (formalized as an equivalence relation), then one may naturally split the set into equivalence classes. These equivalence classes are constructed so that elements and belong to the same equivalence class if, and only if, they are equivalent.

Formally, given a set and an equivalence relation on the equivalence class of an element in is denoted or, equivalently, to emphasize its equivalence relation , and is defined as the set of all elements in with which is -related. The definition of equivalence relations implies that the equivalence classes form a partition of meaning, that every element of the set belongs to exactly one equivalence class. The set of the equivalence classes is sometimes called the quotient set or the quotient space of by and is denoted by

When the set has some structure (such as a group operation or a topology) and the equivalence relation is compatible with this structure, the quotient set often inherits a similar structure from its parent set. Examples include quotient spaces in linear algebra, quotient spaces in topology, quotient groups, homogeneous spaces, quotient rings, quotient monoids, and quotient categories.

Definition and notation

An equivalence relation on a set is a binary relation on satisfying the three properties:[1]

- for all (reflexivity),

- implies for all (symmetry),

- if and then for all (transitivity).

The equivalence class of an element is defined as[2]

The word "class" in the term "equivalence class" may generally be considered as a synonym of "set", although some equivalence classes are not sets but proper classes. For example, "being isomorphic" is an equivalence relation on groups, and the equivalence classes, called isomorphism classes, are not sets.

The set of all equivalence classes in with respect to an equivalence relation is denoted as and is called modulo (or the quotient set of by ).[3] The surjective map from onto which maps each element to its equivalence class, is called the canonical surjection, or the canonical projection.

Every element of an equivalence class characterizes the class, and may be used to represent it. When such an element is chosen, it is called a representative of the class. The choice of a representative in each class defines an injection from to X. Since its composition with the canonical surjection is the identity of such an injection is called a section, when using the terminology of category theory.

Sometimes, there is a section that is more "natural" than the other ones. In this case, the representatives are called canonical representatives. For example, in modular arithmetic, for every integer m greater than 1, the congruence modulo m is an equivalence relation on the integers, for which two integers a and b are equivalent—in this case, one says congruent—if m divides this is denoted Each class contains a unique non-negative integer smaller than and these integers are the canonical representatives.

The use of representatives for representing classes allows avoiding considering explicitly classes as sets. In this case, the canonical surjection that maps an element to its class is replaced by the function that maps an element to the representative of its class. In the preceding example, this function is denoted and produces the remainder of the Euclidean division of a by m.

Properties

For a set with an equivalence relation , every element of is a member of the equivalence class by reflexivity ( for all ). Every two equivalence classes and are either equal if , or disjoint otherwise. Therefore, the set of all equivalence classes of forms a partition of : every element of belongs to one and only one equivalence class.[4]

Conversely, for a set , every partition comes from an equivalence relation in this way, and different relations give different partitions. Thus if and only if and belong to the same set of the partition.[5]

It follows from the properties in the previous section that if is an equivalence relation on a set and and are two elements of the following statements are equivalent:

- ,

- , and

Examples

- Let be the set of all rectangles in a plane, and the equivalence relation "has the same area as", then for each positive real number there will be an equivalence class of all the rectangles that have area [6]

- Consider the modulo 2 equivalence relation on the set of integers, such that if and only if their difference is an even number. This relation gives rise to exactly two equivalence classes: one class consists of all even numbers, and the other class consists of all odd numbers. Using square brackets around one member of the class to denote an equivalence class under this relation, and all represent the same element of [2]

- Let be the set of ordered pairs of integers with non-zero and define an equivalence relation on such that if and only if then the equivalence class of the pair can be identified with the rational number and this equivalence relation and its equivalence classes can be used to give a formal definition of the set of rational numbers.[7] The same construction can be generalized to the field of fractions of any integral domain.

- If consists of all the lines in, say, the Euclidean plane, and means that and are parallel lines, then the set of lines that are parallel to each other form an equivalence class, as long as a line is considered parallel to itself. In this situation, each equivalence class determines a point at infinity.

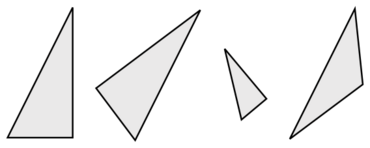

Graphical representation

An undirected graph may be associated to any symmetric relation on a set where the vertices are the elements of and two vertices and are joined if and only if Among these graphs are the graphs of equivalence relations. These graphs, called cluster graphs, are characterized as the graphs such that the connected components are cliques.[2]

Invariants

If is an equivalence relation on and is a property of elements of such that whenever is true if is true, then the property is said to be an invariant of or well-defined under the relation

A frequent particular case occurs when is a function from to another set ; if whenever then is said to be class invariant under or simply invariant under This occurs, for example, in the character theory of finite groups. Some authors use "compatible with " or just "respects " instead of "invariant under ".

Any function is class invariant under according to which if and only if The equivalence class of is the set of all elements in which get mapped to that is, the class is the inverse image of This equivalence relation is known as the kernel of

More generally, a function may map equivalent arguments (under an equivalence relation on ) to equivalent values (under an equivalence relation on ). Such a function is a morphism of sets equipped with an equivalence relation.

Quotient space in topology

In topology, a quotient space is a topological space formed on the set of equivalence classes of an equivalence relation on a topological space, using the original space's topology to create the topology on the set of equivalence classes.

In abstract algebra, congruence relations on the underlying set of an algebra allow the algebra to induce an algebra on the equivalence classes of the relation, called a quotient algebra. In linear algebra, a quotient space is a vector space formed by taking a quotient group, where the quotient homomorphism is a linear map. By extension, in abstract algebra, the term quotient space may be used for quotient modules, quotient rings, quotient groups, or any quotient algebra. However, the use of the term for the more general cases can as often be by analogy with the orbits of a group action.

The orbits of a group action on a set may be called the quotient space of the action on the set, particularly when the orbits of the group action are the right cosets of a subgroup of a group, which arise from the action of the subgroup on the group by left translations, or respectively the left cosets as orbits under right translation.

A normal subgroup of a topological group, acting on the group by translation action, is a quotient space in the senses of topology, abstract algebra, and group actions simultaneously.

Although the term can be used for any equivalence relation's set of equivalence classes, possibly with further structure, the intent of using the term is generally to compare that type of equivalence relation on a set either to an equivalence relation that induces some structure on the set of equivalence classes from a structure of the same kind on or to the orbits of a group action. Both the sense of a structure preserved by an equivalence relation, and the study of invariants under group actions, lead to the definition of invariants of equivalence relations given above.

See also

- Equivalence partitioning, a method for devising software test sets based on program coverage of possible inputs

- Homogeneous space, the quotient space of Lie groups

- Partial equivalence relation – Mathematical concept for comparing objects

- Quotient by an equivalence relation – Generalization of equivalence classes to scheme theory

- Setoid – Mathematical construction of a set with an equivalence relation

- Transversal (combinatorics) – Set that intersects every one of a family of sets

Notes

- ↑ Devlin 2004, p. 122.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Devlin 2004, p. 123.

- ↑ Wolf 1998, p. 178

- ↑ Maddox 2002, p. 74, Thm. 2.5.15

- ↑ Avelsgaard 1989, p. 132, Thm. 3.16

- ↑ Avelsgaard 1989, p. 127

- ↑ Maddox 2002, pp. 77–78

References

- Avelsgaard, Carol (1989), Foundations for Advanced Mathematics, Scott Foresman, ISBN 0-673-38152-8

- Devlin, Keith (2004), Sets, Functions, and Logic: An Introduction to Abstract Mathematics (3rd ed.), Chapman & Hall/ CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-58488-449-1

- Maddox, Randall B. (2002), Mathematical Thinking and Writing, Harcourt/ Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-464976-9

- Stein, Elias M.; Shakarchi, Rami (2012). Functional Analysis: Introduction to Further Topics in Analysis. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400840557. ISBN 978-1-4008-4055-7.

- Wolf, Robert S. (1998), Proof, Logic and Conjecture: A Mathematician's Toolbox, Freeman, ISBN 978-0-7167-3050-7

Further reading

- Sundstrom (2003), Mathematical Reasoning: Writing and Proof, Prentice-Hall

- Smith; Eggen; St.Andre (2006), A Transition to Advanced Mathematics (6th ed.), Thomson (Brooks/Cole)

- Schumacher, Carol (1996), Chapter Zero: Fundamental Notions of Abstract Mathematics, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-82653-4

- O'Leary (2003), The Structure of Proof: With Logic and Set Theory, Prentice-Hall

- Lay (2001), Analysis with an introduction to proof, Prentice Hall

- Morash, Ronald P. (1987), Bridge to Abstract Mathematics, Random House, ISBN 0-394-35429-X

- Gilbert; Vanstone (2005), An Introduction to Mathematical Thinking, Pearson Prentice-Hall

- Fletcher; Patty, Foundations of Higher Mathematics, PWS-Kent

- Iglewicz; Stoyle, An Introduction to Mathematical Reasoning, MacMillan

- D'Angelo; West (2000), Mathematical Thinking: Problem Solving and Proofs, Prentice Hall

- Cupillari, The Nuts and Bolts of Proofs, Wadsworth

- Bond, Introduction to Abstract Mathematics, Brooks/Cole

- Barnier; Feldman (2000), Introduction to Advanced Mathematics, Prentice Hall

- Ash, A Primer of Abstract Mathematics, MAA

|