Ford circle

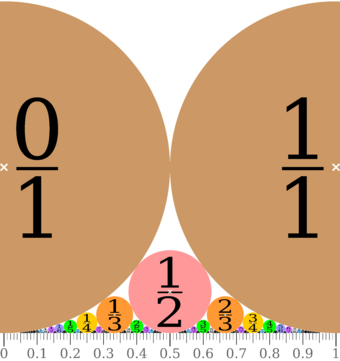

In mathematics, a Ford circle is a circle in the Euclidean plane, in a family of circles that are all tangent to the -axis at rational points. For each rational number , expressed in lowest terms, there is a Ford circle whose center is at the point and whose radius is . It is tangent to the -axis at its bottom point, . The two Ford circles for rational numbers and (both in lowest terms) are tangent circles when and otherwise these two circles are disjoint.[1]

History

Ford circles are a special case of mutually tangent circles; the base line can be thought of as a circle with infinite radius. Systems of mutually tangent circles were studied by Apollonius of Perga, after whom the problem of Apollonius and the Apollonian gasket are named.[2] In the 17th century René Descartes discovered Descartes' theorem, a relationship between the reciprocals of the radii of mutually tangent circles.[2]

Ford circles also appear in the Sangaku (geometrical puzzles) of Japanese mathematics. A typical problem, which is presented on an 1824 tablet in the Gunma Prefecture, covers the relationship of three touching circles with a common tangent. Given the size of the two outer large circles, what is the size of the small circle between them? The answer is equivalent to a Ford circle:[3]

Ford circles are named after the American mathematician Lester R. Ford, Sr., who wrote about them in 1938.[1]

Properties

The Ford circle associated with the fraction is denoted by or There is a Ford circle associated with every rational number. In addition, the line is counted as a Ford circle – it can be thought of as the Ford circle associated with infinity, which is the case

Two different Ford circles are either disjoint or tangent to one another. No two interiors of Ford circles intersect, even though there is a Ford circle tangent to the x-axis at each point on it with rational coordinates. If is between 0 and 1, the Ford circles that are tangent to can be described variously as

- the circles where [1]

- the circles associated with the fractions that are the neighbors of in some Farey sequence,[1] or

- the circles where is the next larger or the next smaller ancestor to in the Stern–Brocot tree or where is the next larger or next smaller ancestor to .[1]

If and are two tangent Ford circles, then the circle through and (the x-coordinates of the centers of the Ford circles) and that is perpendicular to the -axis (whose center is on the x-axis) also passes through the point where the two circles are tangent to one another.

The centers of the Ford circles constitute a discrete (and hence countable) subset of the plane, whose closure is the real axis - an uncountable set.

Ford circles can also be thought of as curves in the complex plane. The modular group of transformations of the complex plane maps Ford circles to other Ford circles.[1]

Ford circles are a sub-set of the circles in the Apollonian gasket generated by the lines and and the circle [4]

By interpreting the upper half of the complex plane as a model of the hyperbolic plane (the Poincaré half-plane model), Ford circles can be interpreted as horocycles. In hyperbolic geometry any two horocycles are congruent. When these horocycles are circumscribed by apeirogons they tile the hyperbolic plane with an order-3 apeirogonal tiling.

Total area of Ford circles

There is a link between the area of Ford circles, Euler's totient function the Riemann zeta function and Apéry's constant [5] As no two Ford circles intersect, it follows immediately that the total area of the Ford circles

is less than 1. In fact the total area of these Ford circles is given by a convergent sum, which can be evaluated. From the definition, the area is

Simplifying this expression gives

where the last equality reflects the Dirichlet generating function for Euler's totient function Since this finally becomes

Note that as a matter of convention, the previous calculations excluded the circle of radius corresponding to the fraction . It includes the complete circle for , half of which lies outside the unit interval, hence the sum is still the fraction of the unit square covered by Ford circles.

Ford spheres (3D)

The concept of Ford circles can be generalized from the rational numbers to the Gaussian rationals, giving Ford spheres. In this construction, the complex numbers are embedded as a plane in a three-dimensional Euclidean space, and for each Gaussian rational point in this plane one constructs a sphere tangent to the plane at that point. For a Gaussian rational represented in lowest terms as , the diameter of this sphere should be where represents the complex conjugate of . The resulting spheres are tangent for pairs of Gaussian rationals and with , and otherwise they do not intersect each other.[6][7]

See also

- Apollonian gasket – a fractal with infinite mutually tangential circles in a circle instead of on a line

- Steiner chain

- Pappus chain

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Fractions", The American Mathematical Monthly 45 (9): 586–601, 1938, doi:10.2307/2302799.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The problem of Apollonius", The American Mathematical Monthly 75 (1): 5–15, 1968, doi:10.2307/2315097.

- ↑ Fukagawa, Hidetosi; Pedoe, Dan (1989), Japanese temple geometry problems, Winnipeg, MB: Charles Babbage Research Centre, ISBN 0-919611-21-4.

- ↑ "Apollonian circle packings: number theory", Journal of Number Theory 100 (1): 1–45, 2003, doi:10.1016/S0022-314X(03)00015-5.

- ↑ Marszalek, Wieslaw (2012), "Circuits with oscillatory hierarchical Farey sequences and fractal properties", Circuits, Systems and Signal Processing 31 (4): 1279–1296, doi:10.1007/s00034-012-9392-3.

- ↑ Pickover, Clifford A. (2001), "Chapter 103. Beauty and Gaussian Rational Numbers", Wonders of Numbers: Adventures in Mathematics, Mind, and Meaning, Oxford University Press, pp. 243–246, ISBN 9780195348002, https://books.google.com/books?id=52N0JJBspM0C&pg=PA243.

- ↑ Northshield, Sam (2015), Ford Circles and Spheres, Bibcode: 2015arXiv150300813N.

External links

- Ford's Touching Circles at cut-the-knot

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Ford Circle". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/FordCircle.html.

- Bonahon, Francis (9 June 2015). "Funny Fractions and Ford Circles" (YouTube video). Brady Haran. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0hlvhQZIOQw. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

|