Descartes' theorem

In geometry, Descartes' theorem states that for every four kissing, or mutually tangent, circles, the radii of the circles satisfy a certain quadratic equation. By solving this equation, one can construct a fourth circle tangent to three given, mutually tangent circles. The theorem is named after René Descartes, who stated it in 1643.

Frederick Soddy's 1936 poem The Kiss Precise summarizes the theorem in terms of the bends (inverse radii) of the four circles:

The sum of the squares of all four bends

Is half the square of their sum[1]

Special cases of the theorem apply when one or two of the circles is replaced by a straight line (with zero bend) or when the bends are integers or square numbers. A version of the theorem using complex numbers allows the centers of the circles, and not just their radii, to be calculated. With an appropriate definition of curvature, the theorem also applies in spherical geometry and hyperbolic geometry. In higher dimensions, an analogous quadratic equation applies to systems of pairwise tangent spheres or hyperspheres.

History

Geometrical problems involving tangent circles have been pondered for millennia. In ancient Greece of the third century BC, Apollonius of Perga devoted an entire book to the topic, Ἐπαφαί [Tangencies]. It has been lost, and is known largely through a description of its contents by Pappus of Alexandria and through fragmentary references to it in medieval Islamic mathematics.[2] However, Greek geometry was largely focused on straightedge and compass construction. For instance, the problem of Apollonius, closely related to Descartes' theorem, asks for the construction of a circle tangent to three given circles which need not themselves be tangent.[3] Instead, Descartes' theorem is formulated using algebraic relations between numbers describing geometric forms. This is characteristic of analytic geometry, a field pioneered by René Descartes and Pierre de Fermat in the first half of the 17th century.[4]

Descartes discussed the tangent circle problem briefly in 1643, in two letters to Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate.[5] Descartes initially posed to the princess the problem of Apollonius. After Elisabeth's partial results revealed that solving the full problem analytically would be too tedious, he simplified the problem to the case in which the three given circles are mutually tangent, and in solving this simplified problem he came up with the equation describing the relation between the radii, or curvatures, of four pairwise tangent circles. This result became known as Descartes' theorem.[6][7] Unfortunately, the reasoning through which Descartes found this relation has been lost.[8]

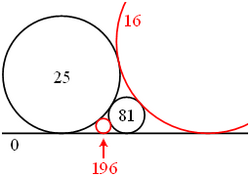

Japanese mathematics frequently concerned problems involving circles and their tangencies,[9] and Japanese mathematician Yamaji Nushizumi stated a form of Descartes’ circle theorem in 1751. Like Descartes, he expressed it as a polynomial equation on the radii rather than their curvatures.[10][11] The special case of this theorem for one straight line and three circles was recorded on a Japanese sangaku tablet from 1824.[12]

Descartes' theorem was rediscovered in 1826 by Jakob Steiner,[13] in 1842 by Philip Beecroft,[14] and in 1936 by Frederick Soddy. Soddy chose to format his version of the theorem as a poem, The Kiss Precise, and published it in Nature. The kissing circles in this problem are sometimes known as Soddy circles. Soddy also extended the theorem to spheres,[1] and in another poem described the chain of six spheres each tangent to its neighbors and to three given mutually tangent spheres, a configuration now called Soddy's hexlet.[15] Thorold Gosset extended the theorem and the poem to arbitrary dimensions.[16] The generalization is sometimes called the Soddy–Gosset theorem,[17] although both the hexlet and the three-dimensional version were known earlier, in sangaku and in the 1886 work of Robert Lachlan.[12][18][19]

A problem involving Descartes' theorem, asking for the height of a circle in a Pappus chain, was one of many "killer" problems used in oral examinations in the Soviet Union to keep Jews out of the Moscow State University mathematics program.[20]

Multiple proofs of the theorem have been published. Steiner's proof uses Pappus chains and Viviani's theorem. Proofs by Philip Beecroft and by H. S. M. Coxeter involve four more circles, passing through triples of tangencies of the original three circles; Coxeter also provided a proof using inversive geometry. Additional proofs involve arguments based on symmetry, calculations in exterior algebra, or algebraic manipulation of Heron's formula (for which see § Soddy circles of a triangle).[21][22]

Statement

Descartes' theorem is most easily stated in terms of the circles' curvatures.[23] The signed curvature (or bend) of a circle is defined as , where is its radius. The larger a circle, the smaller is the magnitude of its curvature, and vice versa. The sign in (represented by the symbol) is positive for a circle that is externally tangent to the other circles. For an internally tangent circle that circumscribes the other circles, the sign is negative. If a straight line is considered a degenerate circle with zero curvature (and thus infinite radius), Descartes' theorem also applies to a line and three circles that are all three mutually tangent (see Generalized circle).[1]

For four circles that are tangent to each other at six distinct points, with curvatures for , Descartes' theorem says:

|

|

|

If one of the four curvatures is considered to be a variable, and the rest to be constants, this is a quadratic equation. To find the radius of a fourth circle tangent to three given kissing circles, the quadratic equation can be solved as[13][24]

|

|

|

The symbol indicates that in general this equation has two solutions, and any triple of tangent circles has two tangent circles (or degenerate straight lines). Problem-specific criteria may favor one of these two solutions over the other in any given problem.[21]

The theorem does not apply to systems of circles with more than two circles tangent to each other at the same point. It requires that the points of tangency be distinct.[8] When more than two circles are tangent at a single point, there can be infinitely many such circles, with arbitrary curvatures; see pencil of circles.[25]

Locating the circle centers

To determine a circle completely, not only its radius (or curvature), but also its center must be known. The relevant equation is expressed most clearly if the Cartesian coordinates are interpreted as a complex number . The equation then looks similar to Descartes' theorem and is therefore called the complex Descartes theorem. Given four circles with curvatures and centers for , the following equality holds in addition to equation (1):

|

|

|

Once has been found using equation (2), one may proceed to calculate by solving equation (3) as a quadratic equation, leading to a form similar to equation (2):

Again, in general there are two solutions for corresponding to the two solutions for . The plus/minus sign in the above formula for does not necessarily correspond to the plus/minus sign in the formula for .[17][26][27]

Special cases

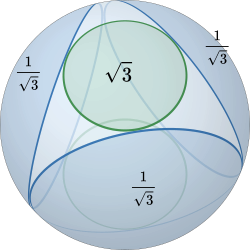

Three congruent circles

When three of the four circles are congruent, their centers form an equilateral triangle, as do their points of tangency. The two possibilities for a fourth circle tangent to all three are concentric, and equation (2) reduces to[28]

One or more straight lines

If one of the three circles is replaced by a straight line tangent to the remaining circles, then its curvature is zero and drops out of equation (1). For instance, if , then equation (1) can be factorized as[29]

and equation (2) simplifies to[30]

Taking the square root of both sides leads to another alternative formulation of this case (with ),

which has been described as "a sort of demented version of the Pythagorean theorem".[23]

If two circles are replaced by lines, the tangency between the two replaced circles becomes a parallelism between their two replacement lines. In this case, with , equation (2) is reduced to the trivial

This corresponds to the observation that, for all four curves to remain mutually tangent, the other two circles must be congruent.[17][24]

Integer curvatures

When four tangent circles described by equation (2) all have integer curvatures, the alternative fourth circle described by the second solution to the equation must also have an integer curvature. This is because both solutions differ from an integer by the square root of an integer, and so either solution can only be an integer if this square root, and hence the other solution, is also an integer. Every four integers that satisfy the equation in Descartes' theorem form the curvatures of four tangent circles.[31] Integer quadruples of this type are also closely related to Heronian triangles, triangles with integer sides and area.[32]

Starting with any four mutually tangent circles, and repeatedly replacing one of the four with its alternative solution (Vieta jumping), in all possible ways, leads to a system of infinitely many tangent circles called an Apollonian gasket. When the initial four circles have integer curvatures, so does each replacement, and therefore all of the circles in the gasket have integer curvatures. Any four tangent circles with integer curvatures belong to exactly one such gasket, uniquely described by its root quadruple of the largest four largest circles and four smallest curvatures. This quadruple can be found, starting from any other quadruple from the same gasket, by repeatedly replacing the smallest circle by a larger one that solves the same Descartes equation, until no such reduction is possible.[31]

A root quadruple is said to be primitive if it has no nontrivial common divisor. Every primitive root quadruple can be found from a factorization of a sum of two squares, , as the quadruple . To be primitive, it must satisfy the additional conditions , and . Factorizations of sums of two squares can be obtained using the sum of two squares theorem. Any other integer Apollonian gasket can be formed by multiplying a primitive root quadruple by an arbitrary integer, and any quadruple in one of these gaskets (that is, any integer solution to the Descartes equation) can be formed by reversing the replacement process used to find the root quadruple. For instance, the gasket with root quadruple , shown in the figure, is generated in this way from the factorized sum of two squares .[31]

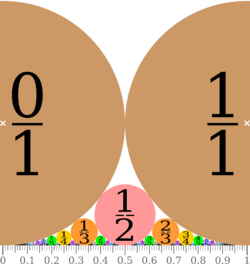

Ford circles

The special cases of one straight line and integer curvatures combine in the Ford circles. These are an infinite family of circles tangent to the -axis of the Cartesian coordinate system at its rational points. Each fraction (in lowest terms) has a circle tangent to the line at the point with curvature . Three of these curvatures, together with the zero curvature of the axis, meet the conditions of Descartes' theorem whenever the denominators of two of the corresponding fractions sum to the denominator of the third. The two Ford circles for fractions and (both in lowest terms) are tangent when . When they are tangent, they form a quadruple of tangent circles with the -axis and with the circle for their mediant .[33]

The Ford circles belong to a special Apollonian gasket with root quadruple , bounded between two parallel lines, which may be taken as the -axis and the line . This is the only Apollonian gasket containing a straight line, and not bounded within a negative-curvature circle. The Ford circles are the circles in this gasket that are tangent to the -axis.[31]

Geometric progression

When the four radii of the circles in Descartes' theorem are assumed to be in a geometric progression with ratio , the curvatures are also in the same progression (in reverse). Plugging this ratio into the theorem gives the equation

which has only one real solution greater than one, the ratio

where is the golden ratio. If the same progression is continued in both directions, each consecutive four numbers describe circles obeying Descartes' theorem. The resulting double-ended geometric progression of circles can be arranged into a single spiral pattern of tangent circles, called Coxeter's loxodromic sequence of tangent circles. It was first described, together with analogous constructions in higher dimensions, by H. S. M. Coxeter in 1968.[34][35]

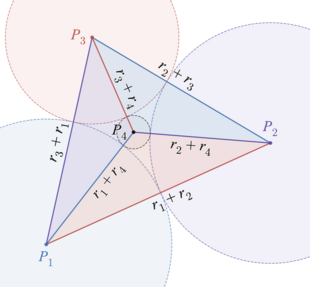

Soddy circles of a triangle

Any triangle in the plane has three externally tangent circles centered at its vertices. Letting be the three points, be the lengths of the opposite sides, and be the semiperimeter, these three circles have radii . By Descartes' theorem, two more circles, sometimes called Soddy circles, are tangent to these three circles. They are separated by the incircle, one interior to it and one exterior.[36][37][38] Descartes' theorem can be used to show that the inner Soddy circle's curvature is , where is the triangle's area, is its circumradius, and is its inradius. The outer Soddy circle has curvature .[39] The inner curvature is always positive, but the outer curvature can be positive, negative, or zero. Triangles whose outer circle degenerates to a straight line with curvature zero have been called "Soddyian triangles".[39]

One of the many proofs of Descartes' theorem is based on this connection to triangle geometry and on Heron's formula for the area of a triangle as a function of its side lengths. If three circles are externally tangent, with radii then their centers form the vertices of a triangle with side lengths and and semiperimeter By Heron's formula, this triangle has area

Now consider the inner Soddy circle with radius centered at point inside the triangle. Triangle can be broken into three smaller triangles and whose areas can be obtained by substituting for one of the other radii in the area formula above. The area of the first triangle equals the sum of these three areas:

Careful algebraic manipulation shows that this formula is equivalent to equation (1), Descartes' theorem.[21]

This analysis covers all cases in which four circles are externally tangent; one is always the inner Soddy circle of the other three. The cases in which one of the circles is internally tangent to the other three and forms their outer Soddy circle are similar. Again the four centers form four triangles, but (letting be the center of the outer Soddy circle) the triangle sides incident to have lengths that are differences of radii, and rather than sums. may lie inside or outside the triangle formed by the other three centers; when it is inside, this triangle's area equals the sum of the other three triangle areas, as above. When it is outside, the quadrilateral formed by the four centers can be subdivided by a diagonal into two triangles, in two different ways, giving an equality between the sum of two triangle areas and the sum of the other two triangle areas. In every case, the area equation reduces to Descartes' theorem. This method does not apply directly to the cases in which one of the circles degenerates to a line, but those can be handled as a limiting case of circles.[21]

Generalizations

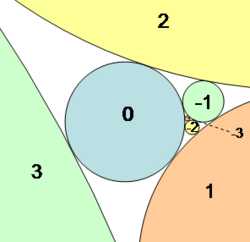

Arbitrary four-circle configurations

Descartes' theorem can be expressed as a matrix equation and then generalized to other configurations of four oriented circles by changing the matrix. Let be a column vector of the four circle curvatures and let be a symmetric matrix whose coefficients represent the relative orientation between the ith and jth oriented circles at their intersection point:

Then equation (1) can be rewritten as the matrix equation[17][40]

As a generalization of Descartes' theorem, a modified symmetric matrix can represent any desired configuration of four circles by replacing each coefficient with the inclination between two circles, defined as

where are the respective radii of the circles, and is the Euclidean distance between their centers.[41][42][43] When the circles intersect, , the cosine of the intersection angle between the circles. The inclination, sometimes called inversive distance, is when the circles are tangent and oriented the same way at their point of tangency, when the two circles are tangent and oriented oppositely at the point of tangency, for orthogonal circles, outside the interval for non-intersecting circles, and in the limit as one circle degenerates to a point.[40][35]

The equation is satisfied for any arbitrary configuration of four circles in the plane, provided is the appropriate matrix of pairwise inclinations.[40]

Spherical and hyperbolic geometry

Descartes' theorem generalizes to mutually tangent great or small circles in spherical geometry if the curvature of the th circle is defined as the cotangent of the oriented intrinsic radius Then:[42][17]

Solving for one of the curvatures in terms of the other three,

As a matrix equation,

The quantity is the "stereographic diameter" of a small circle. This is the Euclidean length of the diameter in the stereographically projected plane when some point on the circle is projected to the origin. For a great circle, such a stereographic projection is a straight line through the origin, so .[44]

Likewise, the theorem generalizes to mutually tangent circles in hyperbolic geometry if the curvature of the th cycle is defined as the hyperbolic cotangent of the oriented intrinsic radius Then:[17][42]

Solving for one of the curvatures in terms of the other three,

As a matrix equation,

This formula also holds for mutually tangent configurations in hyperbolic geometry including hypercycles and horocycles, if is taken to be the reciprocal of the stereographic diameter of the cycle. This is the diameter under stereographic projection (the Poincaré disk model) when one endpoint of the diameter is projected to the origin.[45] Hypercycles do not have a well-defined center or intrinsic radius and horocycles have an ideal point for a center and infinite intrinsic radius, but for a hyperbolic circle, for a horocycle, for a hypercycle, and for a geodesic.[46]

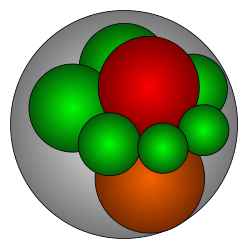

Higher dimensions

In -dimensional Euclidean space, the maximum number of mutually tangent hyperspheres is . For example, in 3-dimensional space, five spheres can be mutually tangent. The curvatures of the hyperspheres satisfy

with the case corresponding to a flat hyperplane, generalizing the 2-dimensional version of the theorem.[17][42] Although there is no 3-dimensional analogue of the complex numbers, the relationship between the positions of the centers can be re-expressed as a matrix equation, which also generalizes to dimensions.[17]

In three dimensions, suppose that three mutually tangent spheres are fixed, and a fourth sphere is given, tangent to the three fixed spheres. The three-dimensional version of Descartes' theorem can be applied to find a sphere tangent to and the fixed spheres, then applied again to find a new sphere tangent to and the fixed spheres, and so on. The result is a cyclic sequence of six spheres each tangent to its neighbors in the sequence and to the three fixed spheres, a configuration called Soddy's hexlet, after Soddy's discovery and publication of it in the form of another poem in 1936.[15][47]

Higher-dimensional configurations of mutually tangent hyperspheres in spherical or hyperbolic geometry, with curvatures defined as above, satisfy

where in spherical geometry and in hyperbolic geometry.[42][17]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "The Kiss Precise", Nature 137 (3477): 1021, June 1936, doi:10.1038/1371021a0, Bibcode: 1936Natur.137.1021S

- ↑ "Arabic traces of lost works of Apollonius", Archive for History of Exact Sciences 35 (3): 187–253, 1986, doi:10.1007/BF00357307

- ↑ "The problem of Apollonius", The Mathematics Teacher 54 (6): 444–452, October 1961, doi:10.5951/MT.54.6.0444

- ↑ Boyer, Carl B. (2004), "Chapter 5: Fermat and Descartes", History of Analytic Geometry, Dover Publications, pp. 74–102, ISBN 978-0486438320

- ↑ Adam, Charles; Tannery, Paul, eds. (1901) (in fr), Oeuvres de Descartes, 4: Correspondance Juillet 1643 – Avril 1647, Paris: Léopold Cerf, "325. Descartes a Elisabeth", Template:Pgs; "328. Descartes a Elisabeth", Template:Pgs Bos, Erik-Jan (2010), "Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia and Descartes' letters (1650–1665)", Historia Mathematica 37 (3): 485–502, doi:10.1016/j.hm.2009.11.004

- ↑ The Correspondence between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and René Descartes, The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe, University of Chicago Press, 2007, pp. 37–39, 73–77, ISBN 978-0-226-20444-4

- ↑ Mackenzie, Dana (March–April 2023), "The princess and the philosopher", American Scientist 111 (2): 80–84, ProQuest 2779946948, https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-princess-and-the-philosopher

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "The problem of Apollonius", The American Mathematical Monthly 75 (1): 5–15, January 1968, doi:10.1080/00029890.1968.11970941

- ↑ Yanagihara, K. (1913), "On some geometrical propositions in Wasan, the Japanese native mathematics", Tohoku Mathematical Journal 3: 87–95

- ↑ Michiwaki, Yoshimasa (2008), "Geometry in Japanese mathematics", in Selin, Helaine, Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, Springer Netherlands, pp. 1018–1019, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_9133

- ↑ Takinami, Susumu; Michiwaki, Yoshimasa (1984), "On the Descartes circle theorem", Journal for History of Mathematics (Korean Society for History of Mathematics) 1 (1): 1–8, https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO198411921896693.pdf

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Japanese temple geometry", Scientific American 278 (5): 84–91, May 1998, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0598-84, Bibcode: 1998SciAm.278e..84R; see top illustration, p. 86. Another tablet from 1822 (center, p. 88) concerns Soddy's hexlet, a configuration of three-dimensional tangent spheres.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Fortsetzung der geometrischen Betrachtungen (Heft 2, S. 161)", Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 1826 (1): Template:Pgs, fig. 2–25 taf. III, January 1826, doi:10.1515/crll.1826.1.252, https://archive.org/details/journalfurdierei1218unse/page/n263/

- ↑ Beecroft, Philip (1842), "Properties of circles in mutual contact", The Lady's and Gentleman's Diary (139): 91–96, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015065987789&view=1up&seq=175

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "The hexlet", Nature 138 (3501): 958, December 1936, doi:10.1038/138958a0, Bibcode: 1936Natur.138..958S

- ↑ "The Kiss Precise", Nature 139 (3506): 62, January 1937, doi:10.1038/139062a0, Bibcode: 1937Natur.139Q..62.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 "Beyond the Descartes circle theorem", The American Mathematical Monthly 109 (4): 338–361, 2002, doi:10.2307/2695498

- ↑ Hidetoshi, Fukagawa; Kazunori, Horibe (2014), "Sangaku – Japanese Mathematics and Art in the 18th, 19th and 20th Centuries", in Greenfield, Gary; Hart, George; Sarhangi, Reza, Bridges Seoul Conference Proceedings, Tessellations Publishing, pp. 111–118, https://archive.bridgesmathart.org/2014/bridges2014-111.html

- ↑ Lachlan, R. (1886), "On Systems of Circles and Spheres", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 177: 481–625; see "Spheres touching one another", pp. 585–587

- ↑ Egenhoff, Jay (December 2014), "Math as a tool of anti-semitism", The Mathematics Enthusiast (University of Montana, Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library) 11 (3): 649–664, doi:10.54870/1551-3440.1320; see question 7, pp. 559–560

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Levrie, Paul (2019), "A straightforward proof of Descartes's circle theorem", The Mathematical Intelligencer 41 (3): 24–27, doi:10.1007/s00283-019-09883-x

- ↑ "On a theorem in geometry", The American Mathematical Monthly 74 (6): 627–640, 1967, doi:10.2307/2314247

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Mackenzie, Dana (January–February 2010), "A tisket, a tasket, an Apollonian gasket", American Scientist 98 (1): 10–14, "All of these reciprocals look a little bit extravagant, so the formula is usually simplified by writing it in terms of the curvatures or the bends of the circles."

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Wilker, J. B. (1969), "Four proofs of a generalization of the Descartes circle theorem", The American Mathematical Monthly 76 (3): 278–282, doi:10.2307/2316373

- ↑ Glaeser, Georg; Stachel, Hellmuth; Odehnal, Boris (2016), "The parabolic pencil – a common line element", The Universe of Conics, Springer, p. 327, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-45450-3, ISBN 978-3-662-45449-7

- ↑ Northshield, Sam (2014), "Complex Descartes circle theorem", The American Mathematical Monthly 121 (10): 927–931, doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.121.10.927

- ↑ Tupan, Alexandru (2022), "On the complex Descartes circle theorem", The American Mathematical Monthly 129 (9): 876–879, doi:10.1080/00029890.2022.2104084

- ↑ This is a special case of a formula for the radii of circles in a Steiner chain with concentric inner and outer circles, given by Sheydvasser, Arseniy (2023), "3.1 Steiner's porism and 3.6 Steiner's porism revisited", Linear Fractional Transformations, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer International Publishing, pp. 75–81, 99–101, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-25002-6, ISBN 978-3-031-25001-9

- ↑ Hajja, Mowaffaq (2009), "93.33 on a Morsel of Ross Honsberger", The Mathematical Gazette 93 (527): 309–312

- ↑ Dergiades, Nikolaos (2007), "The Soddy circles", Forum Geometricorum 7: 191–197, https://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2007volume7/FG200726.pdf

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 "Apollonian circle packings: number theory", Journal of Number Theory 100 (1): 1–45, 2003, doi:10.1016/S0022-314X(03)00015-5

- ↑ Bradley, Christopher J. (March 2003), "Heron triangles and touching circles", The Mathematical Gazette 87 (508): 36–41, doi:10.1017/s0025557200172080

- ↑ McGonagle, Annmarie; Northshield, Sam (2014), "A new parameterization of Ford circles", Pi Mu Epsilon Journal 13 (10): 637–643

- ↑ "Loxodromic sequences of tangent spheres", Aequationes Mathematicae 1 (1–2): 104–121, 1968, doi:10.1007/BF01817563

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Weiss, Asia (1981), "On Coxeter's Loxodromic Sequences of Tangent Spheres", in Davis, Chandler; Grünbaum, Branko; Sherk, F.A., The Geometric Vein: The Coxeter Festschrift, Springer, pp. 241–250, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5648-9_16, ISBN 978-1-4612-5650-2, https://archive.org/details/geometricveincox0000unse/page/243/

- ↑ "Compte rendu de la 19me session de l'association française pour l'avancement des sciences, pt. 2" (in fr). Congrès de Limoges 1890. Paris: Secrétariat de l'association. 1891. Template:Pgs, especially §4 "Sur les intersections deux a deux des coniques qui ont pour foyers-deux sommets d'un triangle et passent par le troisième" [On the intersections in pairs of the conics which have as foci two vertices of a triangle and pass through the third], Template:Pgs.

- ↑ Veldkamp, G. R. (1985), "The Isoperimetric Point and the Point(s) of Equal Detour in a Triangle", The American Mathematical Monthly 92 (8): 546–558, doi:10.1080/00029890.1985.11971677

- ↑ Garcia, Ronaldo; Reznik, Dan; Moses, Peter; Gheorghe, Liliana (2022), "Triads of conics associated with a triangle", KoG (Croatian Society for Geometry and Graphics) (26): 16–32, doi:10.31896/k.26.2, https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/417127

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Jackson, Frank M. (2013), "Soddyian Triangles", Forum Geometricorum 13: 1–6, https://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2013volume13/FG201301.pdf

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Kocik, Jerzy (2007), A theorem on circle configurations Kocik, Jerzy (2010), "Golden window", Mathematics Magazine 83 (5): 384–390, doi:10.4169/002557010X529815, http://lagrange.math.siu.edu/Kocik/papers/gwindow.pdf

Kocik, Jerzy (2019), Proof of Descartes circle formula and its generalization clarified

- ↑ "X. The Oriented Circle", A Treatise on the Circle and the Sphere, Clarendon, 1916, pp. 351–407; also see p. 109, p. 408, https://archive.org/details/circleandsphere00coolrich/page/n354/

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 Mauldon, J. G. (1962), "Sets of equally inclined spheres", Canadian Journal of Mathematics 14: 509–516, doi:10.4153/CJM-1962-042-6

- ↑ Rigby, J. F. (1981), "The geometry of cycles, and generalized Laguerre inversion", in Davis, Chandler; Grünbaum, Branko; Sherk, F.A., The Geometric Vein: The Coxeter Festschrift, Springer, pp. 355–378, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5648-9_26, ISBN 978-1-4612-5650-2, https://archive.org/details/geometricveincox0000unse/page/355/

- ↑ A definition of stereographic distance can be found in Li, Hongbo; Hestenes, David; Rockwood, Alyn (2001), "Spherical conformal geometry with geometric algebra", Geometric Computing with Clifford Algebras, Springer, pp. 61–75, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04621-0_3, ISBN 978-3-642-07442-4, http://geocalc.clas.asu.edu/pdf/CompGeom-ch3.pdf

- ↑ This concept of distance was called the "pseudo-chordal distance" for the complex unit disk as a model for the hyperbolic plane by "§§1.3.86–88 Chordal and Pseudo-chordal Distance", Theory of Functions of a Complex Variable, I, Chelsea, 1954, pp. 81–86, https://archive.org/details/theory-of-functions-of-a-complex-variable-v-i-ii-by-c.-caratheodory-clr/page/n92/

- ↑ Eriksson, Nicholas; Lagarias, Jeffrey C. (2007), "Apollonian Circle Packings: Number Theory II. Spherical and Hyperbolic Packings", The Ramanujan Journal 14 (3): 437–469, doi:10.1007/s11139-007-9052-6

- ↑ Barnes, John (2012), "Soddy's hexlet", Gems of Geometry (2nd ed.), Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 173–177, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30964-9, ISBN 978-3-642-30963-2

|