Steiner chain

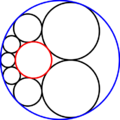

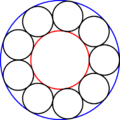

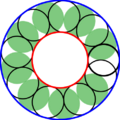

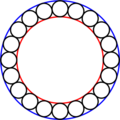

In geometry, a Steiner chain is a set of n circles, all of which are tangent to two given non-intersecting circles (blue and red in Figure 1), where n is finite and each circle in the chain is tangent to the previous and next circles in the chain. In the usual closed Steiner chains, the first and last (n-th) circles are also tangent to each other; by contrast, in open Steiner chains, they need not be. The given circles α and β do not intersect, but otherwise are unconstrained; the smaller circle may lie completely inside or outside of the larger circle. In these cases, the centers of Steiner-chain circles lie on an ellipse or a hyperbola, respectively.

Steiner chains are named after Jakob Steiner, who defined them in the 19th century and discovered many of their properties. A fundamental result is Steiner's porism, which states:

- If at least one closed Steiner chain of n circles exists for two given circles α and β, then there is an infinite number of closed Steiner chains of n circles; and any circle tangent to α and β in the same way[lower-alpha 1] is a member of such a chain.

The method of circle inversion is helpful in treating Steiner chains. Since it preserves tangencies, angles and circles, inversion transforms one Steiner chain into another of the same number of circles. One particular choice of inversion transforms the given circles α and β into concentric circles; in this case, all the circles of the Steiner chain have the same size and can "roll" around in the annulus between the circles similar to ball bearings. This standard configuration allows several properties of Steiner chains to be derived, e.g., its points of tangencies always lie on a circle. Several generalizations of Steiner chains exist, most notably Soddy's hexlet and Pappus chains.[1]

Definitions and types of tangency

- Steiner chains with different internal/external tangencies

-

The 7 circles of this Steiner chain (black) are externally tangent to the inner given circle (red) but internally tangent to the outer given circle (blue).

-

The 7 circles of this Steiner chain (black) are externally tangent to both given circles (red and blue), which lie outside one another.

-

Seven of the 8 circles of this Steiner chain (black) are externally tangent to both given circles (red and blue); the 8th circle is internally tangent to both.

The two given circles α and β cannot intersect; hence, the smaller given circle must lie inside or outside the larger. The circles are usually shown as an annulus, i.e., with the smaller given circle inside the larger one. In this configuration, the Steiner-chain circles are externally tangent to the inner given circle and internally tangent to the outer circle. However, the smaller circle may also lie completely outside the larger one (Figure 2). The black circles of Figure 2 satisfy the conditions for a closed Steiner chain: they are all tangent to the two given circles and each is tangent to its neighbors in the chain. In this configuration, the Steiner-chain circles have the same type of tangency to both given circles, either externally or internally tangent to both. If the two given circles are tangent at a point, the Steiner chain becomes an infinite Pappus chain, which is often discussed in the context of the arbelos (shoemaker's knife), a geometric figure made from three circles. There is no general name for a sequence of circles tangent to two given circles that intersect at two points.

Closed, open and multi-cyclic

- Closed, open and multi-cyclic Steiner chains

-

Closed Steiner chain of nine circles. The 1st and 9th circles are tangent.

-

Open Steiner chain of nine circles. The 1st and 9th circles overlap.

-

Multicyclic Steiner chain of 17 circles in 2 wraps. The 1st and 17th circles touch.

The two given circles α and β touch the n circles of the Steiner chain, but each circle Ck of a Steiner chain touches only four circles: α, β, and its two neighbors, Ck−1 and Ck+1. By default, Steiner chains are assumed to be closed, i.e., the first and last circles are tangent to one another. By contrast, an open Steiner chain is one in which the first and last circles, C1 and Cn, are not tangent to one another; these circles are tangent only to three circles. Multicyclic Steiner chains wrap around the inner circle more than once before closing, i.e., before being tangent to the initial circle.

Closed Steiner chains are the systems of circles obtained as the circle packing theorem representation of a bipyramid.

Annular case and feasibility criterion

- Annular Steiner chains

-

n = 3

-

n = 6

-

n = 9

-

n = 12

-

n = 20

The simplest type of Steiner chain is a closed chain of n circles of equal size surrounding an inscribed circle of radius r; the chain of circles is itself surrounded by a circumscribed circle of radius R. The inscribed and circumscribed given circles are concentric, and the Steiner-chain circles lie in the annulus between them. By symmetry, the angle 2θ between the centers of the Steiner-chain circles is 360°/n. Because Steiner chain circles are tangent to one another, the distance between their centers equals the sum of their radii, here twice their radius ρ. The bisector (green in Figure) creates two right triangles, with a central angle of θ = 180°/n. The sine of this angle can be written as the length of its opposite segment, divided by the hypotenuse of the right triangle

Since θ is known from n, this provides an equation for the unknown radius ρ of the Steiner-chain circles

The tangent points of a Steiner chain circle with the inner and outer given circles lie on a line that pass through their common center; hence, the outer radius R = r + 2ρ.

These equations provide a criterion for the feasibility of a Steiner chain for two given concentric circles. A closed Steiner chain of n circles requires that the ratio of radii R/r of the given circles equal exactly

As shown below, this ratio-of-radii criterion for concentric given circles can be extended to all types of given circles by the inversive distance δ of the two given circles. For concentric circles, this distance is defined as a logarithm of their ratio of radii

Using the solution for concentric circles, the general criterion for a Steiner chain of n circles can be written

If a multicyclic annular Steiner chain has n total circles and wraps around m times before closing, the angle between Steiner-chain circles equals

In other respects, the feasibility criterion is unchanged.

Properties under inversion

- Inversive properties of Steiner chains

-

Two circles (pink and cyan) that are internally tangent to both given circles and whose centers are collinear with the center of the given circles intersect at the angle 2θ.

-

Under inversion, these lines and circles become circles with the same intersection angle, 2θ. The gold circles intersect the two given circles at right angles, i.e., orthogonally.

-

The circles passing through the mutual tangent points of the Steiner-chain circles are orthogonal to the two given circles and intersect one another at multiples of the angle 2θ.

-

The circles passing through the tangent points of the Steiner-chain circles with the two given circles are orthogonal to the latter and intersect at multiples of the angle 2θ.

Circle inversion transforms one Steiner chain into another with the same number of circles.

In the transformed chain, the tangent points between adjacent circles of the Steiner chain all lie on a circle, namely the concentric circle midway between the two fixed concentric circles. Since tangencies and circles are preserved under inversion, this property of all tangencies lying on a circle is also true in the original chain. This property is also shared with the Pappus chain of circles, which can be construed as a special limiting case of the Steiner chain.

In the transformed chain, the tangent lines from O to the Steiner chain circles are separated by equal angles. In the original chain, this corresponds to equal angles between the tangent circles that pass through the center of inversion used to transform the original circles into a concentric pair.

In the transformed chain, the n lines connecting the pairs of tangent points of the Steiner circles with the concentric circles all pass through O, the common center. Similarly, the n lines tangent to each pair of adjacent circles in the Steiner chain also pass through O. Since lines through the center of inversion are invariant under inversion, and since tangency and concurrence are preserved under inversion, the 2n lines connecting the corresponding points in the original chain also pass through a single point, O.

Infinite family

A Steiner chain between two non-intersecting circles can always be transformed into another Steiner chain of equally sized circles sandwiched between two concentric circles. Therefore, any such Steiner chain belongs to an infinite family of Steiner chains related by rotation of the transformed chain about O, the common center of the transformed bounding circles.

Elliptical/hyperbolic locus of centers

The centers of the circles of a Steiner chain lie on a conic section. For example, if the smaller given circle lies within the larger, the centers lie on an ellipse. This is true for any set of circles that are internally tangent to one given circle and externally tangent to the other; such systems of circles appear in the Pappus chain, the problem of Apollonius, and the three-dimensional Soddy's hexlet. Similarly, if some circles of the Steiner chain are externally tangent to both given circles, their centers must lie on a hyperbola, whereas those that are internally tangent to both lie on a different hyperbola.

The circles of the Steiner chain are tangent to two fixed circles, denoted here as α and β, where β is enclosed by α. Let the radii of these two circles be denoted as rα and rβ, respectively, and let their respective centers be the points A and B. Let the radius, diameter and center point of the kth circle of the Steiner chain be denoted as rk, dk and Pk, respectively.

All the centers of the circles in the Steiner chain are located on a common ellipse, for the following reason.[2] The sum of the distances from the center point of the kth circle of the Steiner chain to the two centers A and B of the fixed circles equals a constant

Thus, for all the centers of the circles of the Steiner chain, the sum of distances to A and B equals the same constant, rα + rβ. This defines an ellipse, whose two foci are the points A and B, the centers of the circles, α and β, that sandwich the Steiner chain of circles.

The sum of distances to the foci equals twice the semi-major axis a of an ellipse; hence,

Let p equal the distance between the foci, A and B. Then, the eccentricity e is defined by 2 ae = p, or

From these parameters, the semi-minor axis b and the semi-latus rectum L can be determined

Therefore, the ellipse can be described by an equation in terms of its distance d to one focus

where θ is the angle with the line joining the two foci.

Conjugate chains

- Conjugate Steiner chains with n = 4

-

Steiner chain with the two given circles shown in red and blue.

-

Same set of circles, but with a different choice of given circles.

-

Same set of circles, but with yet another choice of given circles.

If a Steiner chain has an even number of circles, then any two diametrically opposite circles in the chain can be taken as the two given circles of a new Steiner chain to which the original circles belong. If the original Steiner chain has n circles in m wraps, and the new chain has p circles in q wraps, then the equation holds

A simple example occurs for Steiner chains of four circles (n = 4) and one wrap (m = 1). In this case, the given circles and the Steiner-chain circles are equivalent in that both types of circles are tangent to four others; more generally, Steiner-chain circles are tangent to four circles, but the two given circles are tangent to n circles. In this case, any pair of opposite members of the Steiner chain may be selected as the given circles of another Steiner chain that involves the original given circles. Since m = p = 1 and n = q = 4, Steiner's equation is satisfied:

Generalizations

The simplest generalization of a Steiner chain is to allow the given circles to touch or intersect one another. In the former case, this corresponds to a Pappus chain, which has an infinite number of circles.

Soddy's hexlet is a three-dimensional generalization of a Steiner chain of six circles. The centers of the six spheres (the hexlet) travel along the same ellipse as do the centers of the corresponding Steiner chain. The envelope of the hexlet spheres is a Dupin cyclide, the inversion of a torus. The six spheres are not only tangent to the inner and outer sphere, but also to two other spheres, centered above and below the plane of the hexlet centers.

Multiple rings of Steiner chains are another generalization. An ordinary Steiner chain is obtained by inverting an annular chain of tangent circles bounded by two concentric circles. This may be generalized to inverting three or more concentric circles that sandwich annular chains of tangent circles.

Hierarchical Steiner chains are yet another generalization. If the two given circles of an ordinary Steiner chain are nested, i.e., if one lies entirely within the other, then the larger given circle circumscribes the Steiner-chain circles. In a hierarchical Steiner chain, each circle of a Steiner chain is itself the circumscribing given circle of another Steiner chain within it; this process may be repeated indefinitely, forming a fractal.

See also

- Poncelet porism

- Ford circles

- Apollonian gasket

Notes

- ↑ meaning that the arbitrary circle is internally or externally tangent in the same way as a circle of the original Steiner chain

References

Bibliography

- Ogilvy, C. S. (1990). Excursions in Geometry. Dover. pp. 51–54. ISBN 0-486-26530-7. https://archive.org/details/excursionsingeom0000ogil/page/51.

- Coxeter, H.S.M.; Greitzer, S.L. (1967). Geometry Revisited. New Mathematical Library. 19. Washington: MAA. pp. 123–126, 175–176, 180. ISBN 978-0-88385-619-2.

- Johnson RA (1960). Advanced Euclidean Geometry: An elementary treatise on the geometry of the triangle and the circle (reprint of 1929 edition by Houghton Mifflin ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 113–115. ISBN 978-0-486-46237-0.

- Wells D (1991). The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 244–245. ISBN 0-14-011813-6. https://archive.org/details/penguindictionar0000well/page/244.

Further reading

- Eves H (1972). A Survey of Geometry (revised ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-205-03226-6.

- Pedoe D (1970). A Course of Geometry for Colleges and Universities. Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–101. ISBN 978-0-521-07638-8.

- Coolidge JL (1916). A Treatise on the Circle and the Sphere. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 31–37.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Steiner Chain". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SteinerChain.html.

- Interactive animation of a Steiner chain, CodePen

- Interactive Applet by Michael Borcherds showing an animation of Steiner's Chain with a variable number of circles made with GeoGebra.

|