History:Early modern art

Early Modern Art is the period or temporal subdivision of history of art that corresponds to the Early Modern Age. It should not be confused with the concept of modern art, which is not chronological but aesthetic, and which corresponds to certain manifestations of contemporary art.

The chronological period of the Early Modern Age corresponds to the 15th to 18th centuries (with different initial and final milestones, such as the printing press or the Settlement of the Americas, and the French Revolution or industrial revolutions), and historically signified the conformation and subsequent crisis of the Ancien Régime in Europe (a concept that includes the transition from feudalism to capitalism, a classist and pre-industrial society, and an authoritarian or absolute monarchy challenged by the first bourgeois revolutions). Since the Age of Discovery, historical changes accelerated, with the emergence of the modern state, the world-economy, and the scientific revolution; within the framework of the beginning of a decisive European expansion through economy, society, politics, technology, war, religion, and culture. During this period, Europeans expanded mainly in the Americas and the oceanic spaces.

Eventually, already at the end of the period, these processes ended up making Western civilization dominant over the rest of the world's civilizations, and with it determined the imposition of the models proper to Western art, specifically Western European art, which since the Italian Renaissance was identified with an aesthetic ideal formed from the reworking of elements recovered from classical Greco-Roman art, although subjected to a pendular succession of styles (Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassicism, Preromanticism) that either opted for greater artistic freedom or for greater submission to the rules of art institutionalized in the so-called academic art. The social function of the artist began to go beyond that of the mere craftsman to become an individualistic personality, who stood out in the court, or a successful figure in the free market of art. As in the other fields of culture, modernity applied to art meant a progressive secularization or emancipation of the religious that reached its climax with the Enlightenment; although religious art continued to be one of the most, if not the most, commissioned, it no longer had the overwhelming presence it once had during the Medieval Age.

Nevertheless, during the entire period of the Early Modern Age, the main civilizations of the world remained barely influenced, or even almost completely unaffected by the changes undergone by European societies and art, essentially maintaining their own cultural and artistic traits (Indian art, art of China, art of Japan, African art).

Classical Islamic civilization, defined by its intermediate geostrategic position as the main historical competitor of Western Christian civilization — to which it disputed for centuries the Mediterranean space and the Balkans — developed different local modalities of Islamic art in which one can appreciate influences from both Western art and Eastern civilizations.

In the case of American art, the European colonization meant, especially for areas such as Mexico and Peru, the formation of a colonial art with some syncretic characteristics.

In Eastern Europe, Byzantine art continued to survive with Russian art or with some manifestations of Ottoman art.

In addition to the plastic arts, other fine arts — such as music, the performing arts, and literature — had parallel developments, formal analogies, and a greater or lesser aesthetic and, above all, intellectual, ideological, and social coincidence; which has allowed historiography to label their periodization with similar denominations (renaissance music, baroque music, classicism music; renaissance literature, baroque literature, enlightenment or neoclassical literature, etc.) The same can be said of the so-called minor, decorative or industrial arts, which were a faithful reflection of the artistic taste of certain periods — such as the Henry II, Louis XIII, Louis XIV, Regency, Louis XV, Louis XVI, Directoire, and Empire styles, conventionally referred to based on the history of French furniture.[1]

Western European Art

15th and 16th centuries: Late Gothic, Renaissance, and Mannerism

Late Gothic and Northern Renaissance

The preservation of the Gothic tradition, of local characteristics or the greater or lesser influence of the Burgundian-Flemish or Italian Renaissance characterized the diversity of European artistic production throughout the period. Much of the architectural production of the late 15th and early 16th centuries was carried out in national styles that are a natural evolution of Gothic, such as Plateresque or Isabelline Gothic (of debated demarcation) and the Cisneros style in Castile; and the Tudor style or Perpendicular Gothic in England , which evolved into the Elizabethan architecture of the late 16th and early 17th centuries, already strongly influenced by the new Italian Renaissance models. The Gothic pointed arch and the flowery ribbed vaults were replaced by the semicircular arch, the dome, and the architraved elements reminiscent of Rome (pediment, friezes, cornices, classical orders). Even the decoration based on the grotesques recently discovered in Nero's Domus Aurea was imposed.

In painting and sculpture, Northern taste predominated over Italian until the beginning of the 16th century in most of Western Europe, which explains the success of artists such as Colonia, the Egas, Gil de Siloé, Felipe Bigarny, Rodrigo Alemán or Michel Sittow (coming from as far away as the Baltic Hanseatic); although the influence of Italy was also felt, as shown by the European journey of Italian sculptors such as Domenico Fancelli and Pietro Torrigiano — less significant was the emigration of Italian painters, since it is easy to import painting, but it is easier to import the sculptor than the sculptures — and the apprenticeships in Italy of French and Spanish painters such as Jean Fouquet, Pedro Berruguete or Yáñez de la Almedina. But not even in those first decades of the 16th century can it be said that there was an identification of Renaissance Italianism to be bought or imitated with the Florentine-Roman canon or "Vassarian paradigm" (which is what ended up setting the classicist taste perpetuated in the following centuries).[2]

Most of the local production, in all the arts, had a gradual transition between Gothic and Renaissance forms. In Castilian sculpture, this transition was the responsibility of the group formed around the Egas Family, with Juan Guas and Sebastián de Almonacid, while in the crown of Aragon a similar role was played by Damián Forment and in France by Michel Colombe.

Even in Italy itself at the end of the 15th century there was possibly greater interest in Flemish painting than there might have been in Italian painting in Flanders, as shown by the impact of the Portinari Triptych (1476), which had no equivalent in Italian works exported to the Netherlands.[3]

As for the private taste of a monarch of the second half of the 16th century, Philip II of Spain (or as it was qualified, Prince of the Renaissance),[4] the dreamlike and moralistic fantasies of Bosch or the works of such archaizing painters as Marinus and Pieter Coecke were ahead of the Italian masters or other more innovative ones, such as El Greco. Nevertheless, the generation of monarchs of the first half of the century had been seduced by the Italian geniuses of Leonardo da Vinci (François I of France) or Titian (Charles I of Spain, also known as emperor Charles V).

- Late gothic art

The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry, by the Limbourg Brothers (1411-1416)

- Late gothic architecture

Façade of the University of Salamanca (1529-1533)

As for Flanders and Italy, the undisputed brilliance and originality of each of the individual artists and local schools; as well as the fluidity of mutual contacts, both of works (Portinari Triptych) and of masters (Justus of Ghent, Petrus Christus, Roger van der Weyden, Mabuse — they travel from Flanders to Italy — Jacopo de'Barbari, Antonello da Messina — traveling from Italy to Flanders. Antonello's trip, cited by Vasari, is questioned by modern historiography, which only recognizes his coincidence with Petrus Christus in Milan); make it necessary to speak of a shared protagonism that neither prioritizes nor confuses the characteristics of each focus, which are markedly different.[5]

The Flemish-Burgundian region and its natural connection with Italy, the German Rhine area and the upper Danube were of outstanding dynamism in all branches of culture and art, notably in painting, with the decisive innovation of oil painting (the van Eyck brothers) and the development of engraving, which reached extraordinary heights with Albrecht Dürer or Lucas van Leyden, as well as the invention of the printing press (Gutenberg, 1453).

Flemish and German painting were characterized by intense realism and sharpness, and a taste for detail taken to its limit. The school of painters of the 15th century called Flemish Primitives is composed of an extensive list of masters: Roger van der Weyden, Thierry Bouts, Petrus Christus, Hans Memling, Hugo van der Goes, and some anonymous ones whose attribution has managed to be established or is still the subject of debate (Master of Flemalle Robert Campin, Master of Moulins Jean Hey, Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy, Master of the Embroidered Foliage, Master of Alkmaar, Master of Frankfurt, Master of the Legend of Saint Barbara, Master of the Virgo inter Virgines, Master of the View of Saint Gudula, Master of Mary of Burgundy, Master of the Monogram of Brunswick); and that at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th century continued with figures of the size of Bosch, Gerard David, Jan Joest van Calcar, Joachim Patinir, Quentin Metsys or Pieter Brueghel the Elder.

The power of German painting of the time was not limited to Dürer, being seen in the production of artists such as Grünewald, Altdorfer or Lucas Cranach the Elder. There were also fruitful trips of German masters to Italy (Dürer, Michael Pacher),[5] while the transfer of German masters, especially Rhenish, to Flanders was much more abundant.

- Flemish Primitives (15th century)

- Flemish Primitives (16th century)

Italian Renaissance: Quattrocento

Throughout the Middle Ages, Italy had developed artistic productions significantly differentiated from the rest of Western Europe, which, although classified as Romanesque or Gothic, had their own marked characteristics, usually attributed to the survival of the classical Greco-Roman heritage and to contacts with Byzantine art (particularly in Venice — Venetian Gothic architecture — but also in the so-called Roman naturalism — Pietro Cavallini).[6] In addition to the literary precursors of the Renaissance (Dante, Petrarch and Bocaccio), sculptors such as the Pisano, painters of the Sienese school (Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini) and the Florentine school (Giotto, Cimabue), and complete artists such as Arnolfo di Cambio are the immediate precedents of the creative explosion of the Quattrocento (the 1400s in Italian), which began with the frescoes of Fra Angelico and Masaccio, the reliefs of Jacopo della Quercia and the round sculptures of Donatello. The Florence municipality at the beginning of the century held two competitions for the completion of its cathedral that became milestones in the history of art: Brunelleschi's brilliant solution to the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore (1419), and the bronze doors of the Baptistery, by Ghiberti (1401).

- Quattrocento painting

Brera Madonna, by Piero della Francesca (1472)

In the middle of the century, a fortunate set of circumstances came together in the same city, especially the development of humanist philosophy (which developed in anthropocentrics terms new concepts of man and nature, whose mimesis — imitation — would be the function of art) and the presence of a Greek legation at the Council of Florence (1439-1445, which sought Christian unity in the final moments of the resistance of Constantinople against the Turks), which put classical antiquity, its texts and reflection on art theory at the center of intellectual attention. At the same time, artists experienced a decisive social promotion: they became humanists or renaissance men, that is, complete professionals not only of an artistic craft, but of all of them at once, as well as cultivated and literate, which allowed them to be also poets and philosophers, worthy of rubbing shoulders with lay and ecclesiastical aristocrats, princes, kings, and popes, who vied with them and were not ashamed to admire them and treat them with consideration.

The Medici court used patronage as a mechanism of prestige on a scale that allowed it to become an artistic center comparable to the Rome of Augustus or the Athens of Pericles: painters such as Paolo Uccello, Andrea del Castagno, Pollaiuolo, Sandro Botticelli, Pinturicchio, Luca Signorelli, Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli or Benozzo Gozzoli, sculptors such as Luca della Robbia or Andrea Verrocchio, and architects such as Michelozzo, Bernardo Rossellino, and Leon Battista Alberti. The classical vocabulary and the discovery of the laws of linear perspective built the self-conscious theoretical foundations of an art of strong personality, the Florentine school of the quattrocento, which after the decline of the Sienese school (its rival in the duecento and trecento) had become dominant in Italy, characterized by the predominance of disegno (drawing, design). Proof of its prestige was the selection of masters for the pictorial program of the side walls of the Sistine Chapel (1481-1482). It was common for many of the Florentine painters to come from other local Italian schools, such as Piero della Francesca, who came from the school of Ferrara (Francesco del Cossa, Cosimo Tura), Mantegna, who came from the Padua School (Francesco Squarcione, Melozzo da Forli, Filippo Lippi) or Perugino, from the Umbrian school or Marche (Melozzo da Forli, Luca Signorelli). The Venetian school, in turn, was influenced by the Veronese Pisanello and the Sicilian Antonello da Messina (to whom is attributed the introduction of the Flemish technique of oil painting in Italy)[5] to develop very peculiar characteristics focused on the mastery of color, visible in Alvise Vivarini and Carlo Crivelli and that will reach its peak with the Bellini.[7]

- Quattrocento Architecture

Dome of the Florence Cathedral, by Brunelleschi (1420-1436)

Gates to Paradise of the Florence Baptistery, by Ghiberti[8]

Façade of Santa Maria Novella, by Alberti (1458-1478)

- Quattrocento Sculpture

High Renaissance or Classical Renaissance

The brilliant figure of Leonardo da Vinci, who led a wandering life in the Italian and French courts, frames the transition to the Cinquecento (fifteen hundred years in Italian). The so-called High Renaissance or Classical Renaissance[9] begins:

Florence (which had suffered the iconoclastic fury of Savonarola) was replaced as artistic center by Rome, under papal patronage, which attracted Bramante, Michelangelo and Raphael Sanzio, developing the very ambitious artistic program of the Vatican (whose enormous cost was one of the reasons for the discontent generated by the Protestant Reformation), with which we can speak of a Florentine-Roman school (the aforementioned and Fra Bartolommeo, Andrea del Sarto, Giulio Romano, Benvenuto Cellini, Baldassarre Peruzzi, Giovanni Antonio Bazzi (Il Sodoma) and others, whose condition of emulators eclipsed by the genius of their masters, despite their own values, makes them very usually classified as mannerists).[10]

Meanwhile, in Venice, another school developed with its own characteristics. The Venetian School, characterized by the mastery of color (Bellini, Giorgione, Titian).

In relation to the Renaissance of the mid-15th century, characterized by experimentation on linear perspective, the High Renaissance was characterized by the maturity and balance found in Leonardo's sfumato; in the marbled volumes of Michelangelo's terribilità; in the colors, textures and chiaroscuro of the Venetians or in Raphael's Madonnas, which give light and shadows a new prominence, along with their characteristic morbidezza (softness); in the advancement of the arm in the portraits (as in the Gioconda); in the clear composition, especially the triangular, marked by the relationship of the figures with glances and postures, particularly in the hands.[11]

- High Renaissance Painting

Mona Lisa, by Leonardo da Vinci (1503-1506)

- High Renaissance architecture and sculpture

Late Renaissance or Mannerism

- From the sack of Rome of 1527, the Renaissance overcame its classicist phase to experiment with more formal freedom and less subjection to balances and proportions, exaggerating features, introducing breaks and inversions of the logical order, giant orders, dynamic forms such as the serpentinata, and giving way to sophisticated intellectual and iconographics winks or humor. The long-lived Michelangelo and Titian continued their enormous oeuvre, while new generations of artists imitated their maniera (quasi-deified by early art historians such as Vasari) or developed their own creativity:[12]

Painters

- Pontormo (The Deposition from the Cross, 1528)

- Correggio (Adoration of the Shepherds, 1530)

- Parmigianino (Madonna of the Long Neck, 1540)

- Bronzino (Portrait of Lucrezia Panciatichi, 1540)

- Tintoretto (Lavatorium, 1549)

- Veronese (Wedding at Cana, 1563)

- Sebastiano del Piombo

- Arcimboldo

- Jacopo Bassano

- Palma Vecchio

Sculptors

- John of Bologna (Hercules and the centaur Nessus, 1550)

- Benvenuto Cellini (Saltcellar of Francis I of France, 1543)

Architects

- Serlio (The Seven Books of Architecture published between 1537 and 1551)

- Palladio (Teatro Olimpico, 1580)

- Vincenzo Scamozzi

- Vignola

- Giacomo della Porta

Complete artists

- Giulio Romano (building and frescoes of the Palazzo Te, 1524–1534)

- Jacopo Sansovino (interventions around St. Mark's Square in Venice from 1529, such as the Biblioteca Marciana, 1537–1553)

- Bartolomeo Ammannati (Fountain of Neptune, extension of the Palazzo Pitti, 1558–1570)

- Federico Zuccari (Palazzo Zuccari, an extravagant and personal project for his own dwelling in Rome, 1590).

- Late Renaissance Painting

- Late Renaissance architecture and sculpture

Palazzo Farnese[13]

Throughout the rest of Europe, an italianized style spreads, which acquires peculiar characteristics in each area:

In France the Fontainebleau school, painters such as François Clouet, sculptors such as Jean Goujon, Ligier Richier or Germain Pilon and the embellishment of the elegant Châteaux of the Loire Valley (enlargement of Château de Blois and construction of Château de Chambord, both by Domenico da Cortona; Serlio and Gilles le Breton at the palace of Fontainebleau itself; Pierre Lescot at the Louvre Palace; Philibert de l'Orme at the Tuileries.)[14]

In Spain the sculptors Alonso Berruguete, Diego de Siloé, Juan de Juni or Gaspar Becerra; the painters Luis de Morales, Juan de Juanes, Juan Fernández Navarrete, Alonso Sánchez Coello or Juan Pantoja de la Cruz; and the architects Pedro Machuca, Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón, Alonso de Covarrubias or the Vandelvira.

In the Flanders that was divided by the revolution that brought the Protestant Reformation there were Quentin Metsys, Antonio Moro or Karel van Mander (the Vasari of the North).

In Germany Lucas Cranach the Younger or Hans Holbein the Younger (who finished his career in England). And in England, Inigo Jones.

- Italianized painting

- Italianized architecture and sculpture

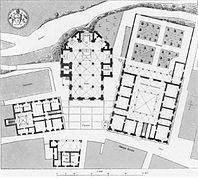

The Late Renaissance in Spain coincides with the beginning of the Golden Age of the arts.[15] After the High — in which the purist or classicist models of the Roman were incorporated[16] (Palace of Charles V, Cathedral of Granada, Jaén Cathedral, Cathedral of Baeza, Seville City Hall), in the last third of the 16th century an ambitious program of marked originality was developed, centered on the Monasterio El Escorial (Juan Bautista de Toledo, Giovanni Battista Castello, Francesco Paciotto, Juan de Herrera — whose strong personality usually makes him be considered the main author — and Francisco de Mora, 1563–1586), which gave Italian painters such as Pellegrino Tibaldi and Federico Zuccaro much work to do, but where there was no place, despite his genius, for an underappreciated artist by Felipe II: El Greco.

- Late Renaissance in Spain

Monasterio de El Escorial, Juan de Herrera (1563-1586)

- Custodia de Arfe.jpg

Monstrance of the Seville Cathedral, by Juan de Arphe (1576)

- Monastery of El Escorial 12.jpg

Philip II Cenotaph in the Basílica of El Escorial, by Leone Leoni and Pompeo Leoni (1587)

- El Expolio, por El Greco.jpg

El expolio, by El Greco (1590-1595)

17th Century and first half of the 18th Century: Baroque, Classicism, and Rococo

Baroque

In 1600s Italy, mannerist intellectualism gave way to a more popular art: the baroque, which appeals directly to the senses and in which a fundamental value is given to the play of light and shadow, to sophisticated geometric shapes (such as the ellipse and the helix), to movement, to violence in contrasts and to the contradiction between appearance and reality. From its inception, it is given simultaneously with a classicist tendency visibly opposed.

The periodization of the baroque allows us to identify several phases: a tenebrist baroque at the beginning of the 17th century, a full or mature baroque in the central decades of the century, and a triumphant or decorative baroque at the end of the 17th century, which was prolonged in the 18th century with the so-called late baroque, of imprecise differentiation with the rococo, a style that can also be defined under very different parameters.[17]

The leading Italian Baroque painters of the 17th century were Caravaggio, whose brief and scandalous career started a true pictorial revolution (and whose style is sometimes referred to as Caravaggioism, as tenebrism or naturalism); followed by il Spagnoleto José de Ribera (a Valencian whose work was entirely carried out in Naples), Pietro da Cortona (also an architect) and Luca Giordano (called Luca fa presto for his speed of execution). The protagonist of the triumph of the twisted forms of the Baroque style in classicist Rome (where the academics of St. Luke maintained the dominance of academicist taste in painting) was a true complete artist:

Bernini, who applied to sculpture and architecture a new sensitive, almost sensual vision (Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, St. Peter's Baldachin); although others such as Borromini, the Maderno and the Fontana also left their mark on an increasingly dazzling Eternal City, confirmed as the center of European art. All of their art was an effective mean of propaganda (in full Propaganda Fide of the Counter-Reformation) at the service of the Catholic Church, which intended to occupy all public and private spaces. The colonnade of St. Peter's Square in Rome literally opens like an embrace "to the city and to the world" (urbi et orbi).[18]

Other Italian cities developed more modest but no less interesting programs, such as the emerging Turin of the Savoy, with the buildings of Guarino Guarini, and others such as Lecce, Naples, Milan, Genoa, Florence, and Venice.[19]

- Baroque painting

Magdalene with the Smoking Flame, by Georges de La Tour (1625-1650)

A game shop, by Frans Snyders.

Portrait of Charles I of England, by Van Dyck (1635)

Juicio de Paris, by Rubens (1638)

Bodegón, by Zurbarán (1650).

Local ecclesiastical institutions and the Catholic Hispanic Monarchy — especially with the artistic and collector program of Philip IV (Buen Retiro Palace, Hall of Realms, Torre de la Parada),[20] which continued despite the economic hardships of the decadence and the difficult juncture of the reign of Charles II — were the main clients of an unrepeatable constellation of painting geniuses: Ribera (in Naples); Ribalta, Velázquez, Murillo, Zurbarán, Alonso Cano, Valdés Leal, Claudio Coello (in Spain); Rubens, Jordaens (in Flanders). Even leading Italian figures such as Tiepolo and Luca Giordano were recruited. Polychrome wood imagery reached unparalleled heights with Gregorio Fernández, Alonso de Mena, Pedro de Mena and Martínez Montañés.

- Baroque architecture

- Casa de la Panaderia en la Plaza Mayor de Madrid.jpg

Casa de la Panadería of the Plaza Mayor de Madrid, byJuan Gómez de Mora (1619), with the Philippe III equestrian statue, by Pietro Tacca (1616)[21]

- San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (Rome) - Dome HDR.jpg

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane elliptical dome by Borromini (1634-1637)

San Marcello al Corso Church, by Carlo Fontana (1682-1683)

Brussels' Grand Place (1695-1699).

- Baroque sculpture

Lying Christ, by Gregorio Fernández (1620-1625)

- St. Peter's Baldachin by Bernini.jpg

St Peter's Baldachin, by Bernini (1624-1633)

- Teresa von Avila Bernini3.JPG

Capilla Cornaro of the Saint Mary of Victories church in Rome, with Bernini's Ecstasy of Saint Theresa (1647-1652)

- Louvre statue DSC00917.jpg

Milon of Croton, by Pierre Puget (1671-1682)

In the Protestant countries, the Baroque was a bourgeois art of private initiative, with Dutch baroque painters such as Rembrandt, Johannes Vermeer, Frans Hals or Salomon van Ruysdael, who worked for the free market.

Anton van Dyck found his audience in England, whose peculiar socio-political-religious situation was an intermediate between the two alternatives of the time.

In France, although some painters such as the Le Nain brothers or Georges de La Tour, and sculptors such as Pierre Puget or François Girardon could easily be inscribed within the parameters of the Baroque, the dominant current was ascribed to the canons of classicism.

- Baroque painting

The Martyrdrom of Saint Philip, by José de Ribera (1639)

Peasant Meal, by Louis Le Nain (1642)

- The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede 1670 Ruisdael.jpg

The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede, by Ruysdael (1670).

- In ictu oculi.jpg

In ictu oculi, one of the Allegories of the Hospital de la Caridad (Sevilla), by Valdés Leal (1672)

Classicism

The academies that were created, first in Renaissance Italy, and then in Spain, England and France, established an aesthetic taste that placed the norms codified by the art treatises above creative fantasy. In the second half of the 17th century, France became the center of this classicist movement, although Italy inspired it in its first half (Annibale Carracci, Guido Reni, Domenichino, Guercino, Accademia di San Luca). The painter Nicolas Poussin, who spent most of his artistic life in Rome, and the sculptor Jacques Sarazin, were both French.[22]

The highest expression of French classicism was the artistic program designed around the Palace of Versailles, built on the outskirts of Paris as a key piece of a broader program of political and social engineering for the settlement of the absolute monarchy of Louis XIV (painters such as Hyacinthe Rigaud or Charles Le Brun, architects such as Louis Le Vau or the Mansart, sculptors such as Coysevox or Puget, and even the garden designer Le Nôtre).

The reconstruction after the Great Fire of London of 1666 allowed urban designs and singular buildings in which classicist criteria predominated, while the country villas were designed with a Palladian style in mind. A taste is established that over time will determine the differences between the English garden artificially naturalistic versus the formal purity of the lines of the French garden.

- Classicist painting

Pietà, by Annibale Carracci (1603)

Atalanta and Hippomenes, by Guido Reni (1615-1625)

- Classicist architecture and sculpture

- Le chateau de Vaux le Vicomte.jpg

Vaux-le-Vicomte, by the architect Luis Le Vau and the landscape designer Le Nôtre (1658-1661)

- Parc chateau versailles.jpg

Palace of Versailles, by the same artists (1661-1692)

- Right caryatids Pavillon Horloge Louvre.jpg

Caryatides in the Louvre, by Jacques Sarazin (1639 a 1642)

Rococo

Although the origin of the term is derogatory, intended to ridicule the twisted decoration of rocailles and coquilles typical of the also called Louis XVI style, as with Mannerism, Rococo was eventually defined as an autonomous style, and like the former, an exhibition organized by the Council of Europe gave it definitive historiographical prestige (Munich, 1958).[23]

Throughout the first two-thirds of the 18th century, there were palaces build in imitation of Versailles all over Europe. Some examples of this are: Royal Palace of Madrid and La Granja in Spain, Winter Palace and Catherine Palace in St. Petersburg, Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, Sanssouci in Prussia, Zwinger in Dresden, Ludwigsburg in Württemberg, Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen, Caserta in Naples. In England there were no Versailles palaces, and the most important of the 18th century buildings was the Blenheim Palace by John Vanbrugh, an extension of the English classicist baroque and anticipator of neoclassicism.[24]

These were supposed to highlight the greater glory of the absolute monarchies in the process of becoming enlightened despotisms, as they filled their interior spaces with an intimate art, private and even secret, of great sensuality, represented in French painting by Watteau, Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Boucher and Fragonard; crystals (La Granja), watches (Real Fábrica de Relojes), furniture, and in the exquisite care taken in the manufacture and installation of porcelains — that were the great technological novelty of the time and were made by some of the best sculptors: Meissen (Johann Joachim Kändler), Augarten, Nymphenburg (Franz Anton Bustelli), Berlin, Vincennes, Sèvres (Étienne-Maurice Falconet), Lomonosov, Chelsea, Buen Retiro, Alcora,[25] etc.

Stucco became a material widely used for the creation of complex architectural-sculptural spaces (Giacomo Serpotta); while pastel in painting (Chardin) and terracotta in sculpture (Clodion) became the preferred techniques for the consumption of a large market demanding small and elegant pieces. The Italian vedutisti, especially the Venetian Canaletto and Guardi, were stimulated by the continuous demand of the first aristocratic tourists visiting the European art circuit (the Grand Tour).

- Rococo architecture

St Charles Church , by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach (1716-1737)

Palace of Sanssouci by Von Knobelsdorff (1745-1747)

- Wieskirche 003.JPG

Church of Wies, by the stuccoists and architects Dominikus and Johann Baptist Zimmermann (1745-1754)

Asamkirche in Múnich, by brothers Egid Quirin Asam and Cosmas Damian Asam (1733-1746)

Facade of the Obradoiro in the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral, by Fernando de Casas Novoa (1740)

- Dosaigues porta.jpg

Palace of the Marqués de Dos Aguas, by Ignacio Vergara and Hipólito Rovira (c. 1740)

At the same time, in more public settings, English painting was making similar aesthetic proposals with the conversation pieces and the satirical painting of Hogarth (who also reflected theoretically on The curve of beauty predominant in Rococo art — the so-called serpentine, serpentinata or sigmoid)[26] and the elegant carelessness of Gainsborough's portraits and landscapes. The prolongation in time of the High German Baroque decomposed the interior spaces of churches (pulpits, altars, pillars, vaults) making the extravagant decoration become the only visible structural element;[27] while the Spanish Churrigueresque twisted the Baroque fantasy to the limit and Salzillo continued the imagery tradition. Goya's cartones, despite their dating in the second half of the century, are included in an artistic taste similar to rococo, a sign of its survival at a time when the crisis of the Ancien Régime confronted that aristocratic taste with the bourgeois rationality and sobriety that was imposed in the French Revolution (1789).

- Rococo painting

- Каналетто. Праздник обручения веницианского дожа с Адриатическим морем.jpg

Marriage of the Sea ceremony, by Canaletto (1729-1730)

Marriage-A-La-Mode, by Hogarth (1745)

The Swing, by Fragonard (1767)

- Rococo sculpture

El Transparente, by Narciso Tomé (1729-1732)

- Laoraciondelhuertomurcia.JPG

The Agony in the Garden, by Salzillo (1754)

Amour menaçant, by Étienne-Maurice Falconet (1757)

Second half of the 18th century and first quarter of the 19th century: Neoclassicism and Preromanticism

By the middle of the 18th century a veritable archaeological fever had broken out, culminating in the discovery of the ruins of Pompeii in 1748. Knowledge of the ancient world was revised with new criteria established intellectually by treatises, scholars, critics and art historians. Some oriented taste in a classical sense (Milizia, Mengs, Winckelmann, Diderot, Quatremère de Quincy) and others in a sense that preludes romanticism, neo-Gothic and the historicisms of the 19th century (Walpole, Lessing, Goethe). The opposition between the neoclassical and the romantic sensibility has become a cultural cliché, reinforced by spectacular generational confrontations such as the one that involved the so-called battle of Hernani (Comédie-Française, February 28, 1830, when the audience of Victor Hugo's play clashed, divided between the Chevelus, young, romantic, hairy men, and the Genoux, old, bald, neoclassical men) or the Salon de Paris of 1819 in which the supporters of the morbid romanticism of Géricault'sThe Raft of the Medusa with those of the neoclassical neatness of Girodet's Pygmalion and Galatea (who won the prize).

- David-Oath of the Horatii-1784.jpg

Oath of the Horatii, by Jacques-Louis David (1784)

Bataille d'Hernani, Satirical engraving by J. J. Grandville (1830)

However, in reality, neoclassicism is also a revolutionary aesthetic and it had its own youthful generational rupture in the exhibition of the Oath of the Horatii by Jacques Louis David at the Salon of 1785 (the scandal of its relegation by the academics forced the modification of its place in the exhibition, and thus its political reading got extended). On the other hand, literary romanticism was the aesthetic choice of the reactionarys (Chateaubriand). The coexistence of neoclassical and romantic sensibility was possible to such an extent that, to denominate the neoclassical architecture of the first half of the 19th century, it has been proposed to use the term romantic classicism, despite the oxymoron (opposition of terms), since, in addition to coinciding in time it also shares stylistical features with the romantic aesthetic by adding some expressiveness and exalted spirit to the simplicity and clarity of the classical Greco-Roman architecture structures.[28]

- Neoclassicist and Preromantic painting

Still Life with Salmon, Lemon and three Vessels by Luis Eugenio Meléndez (1772)

- Reynolds Portrait of Miss Anna Ward with Her Dog Kimbell.jpg

Portrait of Miss Anna Ward with Her Dog, by Joshua Reynolds (1787)

- Neoclassicist architecture

Puerta de Alcalá in Madrid, by Francesco Sabatini (1778)

In the second half of the 18th century, urban halls designs in the Baroque tradition were common but subject to new conventions. The destruction of the Praça do Comércio in Lisbon by the 1755 earthquake allowed its reconstruction as an open space subject to classical canons. In Madrid, the Paseo del Prado (from 1763) brought together an impressive architectural and sculptural ensemble designed mainly by Juan de Villanueva (Prado Museum, Cibeles fountain, Neptune fountain, Botanical Garden, Spanish National Observatory).

Under the criteria of Georgian architecture, the urbanism of Bath was designed (Royal Crescent and John Wood, 1767–1774). With a much more neoclassical conception, in Munich the Königsplatz and its buildings were designed by Karl von Fischer and Leo von Klenze (from 1815). While German and English architecture opted for a neo-Greek historicism, French architecture, especially with Napoleon, opted for Roman models (Church of La Madeleine, conceived by the emperor himself for Temple to the Glory of the Grande Armée and which reproduced the model of the Maison Carrée of Nîmes, Pierre Contant d'Ivry, 1806).[28]

In the Anglo-Saxon world, Palladianism, villa architecture triumphant in England since the end of the 17th century, spread to the newly independent United States. The ceramics of Josiah Wedgwood had a great popularizing impact on neoclassical forms through the pure silhouettes and bas-reliefs of John Flaxman. In France, visionary architects such as Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux proposed buildings based on the spectacular combination of geometric forms, while the mainstream established a more sober neoclassicism (Ange-Jacques Gabriel, Jean Chalgrin, Jacques-Germain Soufflot).

In Spain, academic critics (Antonio Ponz, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando) were quick to denounce Baroque architecture, whose twisted forms gave way to the purity of lines of Ventura Rodríguez or Juan de Villanueva.

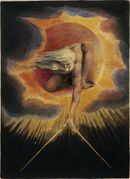

Canova and Thorvaldsen interpret the new taste of the so-called Empire style in a neoclassical sculpture of high formal perfection. As for the evolution of painting, in Germany there were Runge and Friedrich; in England Joshua Reynolds, Henry Fuseli, William Blake, Constable, Turner; in France Jacques Louis David, François Gérard and Ingres; and in Spain the exceptional figure of Goya. These are the artists who close the 18th century and open the artistic world to the 19th.

- Neoclassicism and Preromanticism

The Ancient of Days, in watercolor, by William Blake (1794)

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, from the show Los caprichos by Goya (1799)

- Joseph Mallord William Turner 024.jpg

Calais Pier, by Turner (1803)

- Chistinendenkmal Augustinerkirche.JPG

Tomb of Duchess Maria Christina of Saxony-Teschen, by Canova (1805)

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, by Friedrich (1815)

Art in other spaces of western civilization

Colonial, Spanish-American or Indiano and Spanish-Filipino art

The Spanish-American colonial art or Indiano[29][30] in the Early Modern Age shows the same succession of styles as European art, given that the Spanish colonization of America meant the end of the production of artistic representations of pre-Columbian art, and in many cases even the physical destruction of the previous works of art. Even the urban layout of the cities imposed a new plan, with an orthogonal plan in which the Plaza de Armas housed the main civil and religious buildings. Nevertheless, the autochthonous characteristics survived, even if only as a substratum (sometimes literally, as in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Mexico or in the Inca walls that serve as a plinth for later constructions). In many cases, a true cultural syncretism took place, just as in popular religiosity. There was a synthesis between European styles and ancient local traditions, generating a symbiosis that gave a very particular and characteristic aspect to colonial art.

Its main examples were produced in the two most important viceregales: Viceroyalty of New Spain (Novo-Hispanic Baroque) and Viceroyalty of Peru (Cuzco school of painting). In painting and sculpture, in the early stages of colonization, the importation of European works of art, mainly Spanish, Italian and Flemish, was frequent, but soon began its own production, which incorporated unmistakably American features to the conventions of the different artistic genres.

- Colonial art

Our Lady of Guadalupe (México) (1531 or 1555)

Ángel arcabucero, Maestro de Calamarca, escuela del Collao, Bolivia (17th century)

Adoration of the Magi, Cusco school (1740-1760)

Crucified Christ, Valencian monastery (17th century)

The transoceanic contacts of Mexico with the Philippines (Manila Galleon from Acapulco) gave way to another particular syncretism detectable in some works on both sides of the Pacific, especially in ceramics, folding screens or crucified Christs and other ivory figures with oriental features, called Hispano-Philippine ivories, although some were made in Mexico itself. In an equivalent context, Luso-Indian ivories were also produced.[31][32][33]

- Colonial architecture

Basilica Cathedral of Santa María la Menor (1523-1541)

Church of Santa Prisca de Taxco, México (1751-1758)

Church of La Compañía, Quito, Ecuador (1605-1765)

Basílica de Congonhas, Brasil, with prophet figures by Antonio Francisco Lisboa el Aleijadinho (1796-1799)

Church of Paoay, Luzón, Philippines (1694-1710)

Russian art

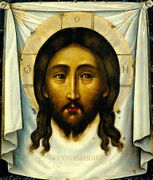

Russian culture and art, like the Slavic cultures of the Balkans and Ukraine , was defined throughout the Middle Ages with a strong influence of Byzantine art, and that influence continued even after the Fall of Constantinople, coinciding with the construction of the Russian state around the figure of the tsar as a continuity of the figure of the basileus and the image of Russia as a Third Rome.

The production of icons and manuscript illumination continued in the centuries of the Early Modern Age with similar conventions and stereotyped features to those of medieval Byzantium. With the westernization program of Peter I the Great, from the end of the 17th century local painters were sent to learn in Italy, France, England and, Holland, and painters from those countries were hired.

Architecture, while continuing to be influenced mainly by Byzantine architecture in the early modern centuries, witnessed the introduction of Renaissance trends by Italian artists such as Aristotle Fioravanti (1415-1486), who had earlier worked for Matthias Corvinus in Hungary. The constructions of the period had a great capacity for inclusion of multiple elements (skirted roofs of Asian origin, the onion dome of Byzantine origin), all reinterpreted with great fantasy and color, as in the St. Basil's Cathedral and the "flamboyant style" of the ornamentation of Moscow and Yaroslavl in the 17th century. Around 1690 there is talk of a Muscovite Baroque (Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli).

During the 18th century the westernization becomes more and more profound, culminating in the construction program of St. Petersburg with neoclassical criteria.[34]

- Russian art

Dormition Cathedral in Moscow, one of the oldest buildings in the Kremlin, inspired by the Dormition Cathedral in Vladimir (1475-1479)

Oriental art

- Oriental art has been defined as a concept in contrast to Western art and through studies carried out by Western art historians, seduced precisely by its otherness. Romantic exoticism degenerated into an orientalism that, to a large extent, was mistifying.

As a general principle, and in spite of its multiplicity, Oriental art is considered more stable over time than the Western art of the Early Modern Age, which was subject to continuous lurches in the succession of styles. Especially stable was the Far Eastern art, repetition of models fixed in the ancient art of its civilizations. On the other hand, the Islamic art (to a large extent, that of a syncretic and transmissive civilization, as Western as Eastern, which had its golden age in the medieval art) and the art of India were more sensitive to all kinds of influences, coming from both East and West.[35]

Islamic art

African-Islamic art

The African space, despite its western geographical location, was largely in the cultural and artistic orbit of the Near East and the Arab-Islamic civilization, especially Egypt and the Maghreb (a term that means precisely The West in Arabic). The same can be said of large parts of East Africa — with the exception of Ethiopia, which remained a Christian kingdom.

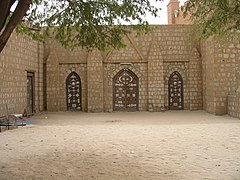

Timbuktu was the main center of Islamic culture in the sub-Saharan space from the end of the Middle Ages, with the Songhay Empire, succeeded by the Moroccan occupation since the 16th century.

Other areas of western and southern Africa continued with their ancestral cultural dynamics, although subjected to the negative impact of European and Arab expansion (direct colonization of the main ports and the slave trade, which profoundly modified the political entities and indigenous social and cultural networks).

- African-Islamic art

Djinguereber Mosque, 14th century.[36]

Sankore Madrasah, reconstructed in 1581.

Ottoman-Turkish art

Ottoman art was produced mainly in Asia Minor and the Balkans, extending its influence throughout the Muslim Mediterranean world.

The classical period of Ottoman architecture (15th to 17th centuries) is dominated by the Armenian Mimar Sinan, who combined the Byzantine tradition with ethnic elements of different origins. To him are due 334 buildings in various cities (mosques Sehzade Mosque, Suleiman and Rustem Pasha Mosque in Istanbul, Selim in Edirne, mausoleums of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, his wife Roxelana, and Sultan Selim II, etc.).

The influence of Western European art had been felt since the late 15th century, when the Venetian painter Gentile Bellini traveled to Istanbul to work for Sultan Mehmed II (1479). During the Tulip period (1718-1730) there was a renewal of interest in Western European art, and a French architect, Mellin, would work for the Ottoman court. In the following period, characterized by Baroque-like forms, the architect Mimar Tahir stands out.

- Ottoman-Turkish art

Şehzade Mosque in Istanbul, by Mimar Sinan (1543-1548)

Persian art

During the 17th century the great Safavid mosques of Khorasan, Isfahan and Tabriz were erected; and the space of Naghsh-i Jahan Square in Isfahan, one of the most spectacular urban landmarks of Islamic cities. The use of glazed ceramic gives the surfaces their textural and chromatic characteristics. Earlier, the Golestan Palace (1524-1576) had been built in Tehran. It was an artistic program oriented to the ostentation of power and luxury, with intimate and pleasant spaces that evoke the Alhambra and the orientalistic-romantic stereotype of the palace of the thousand and one nights; it was deeply renovated in the 18th and 19th centuries.[37]

Persian miniatures obviated the Islamic prohibition of representing human figures because of the particular interpretation of that precept in Shiism, and developed a particularly refined style that was shared, through close contacts with Central Asia, with the art of India. They were characterized by the exquisite treatment of the margins and the conventional use of elements of poetic-mystical interpretation, such as wine (another Islamic prohibition) and gardens, evoking Paradise.[38][39][40]

The most important production centers of Persian carpets were Tabriz (1500-1550), Kashan (1525-1650), Herāt (1525-1650) and Kerman (1600-1650).

- Persian art

Traditional Tabriz carpet of wool and silk.

- Tabriz blue mosque door.jpg

Interior door of the Blue Mosque of Tabriz

Mughal and Indian art

The Mughal Empire promoted the Islamization of northern India , turning the mosque into a religious building competitive with the Hindu temples, yainas or Buddhist. Fatehpur Sikri, a city built between 1569 and 1585, combined Islamic elements (vaults, arches and wide courtyards) with traditional Hindu materials and decoration. Shah Jahan, from the restored capital of Delhi, promoted buildings such as the Red Fort and the Taj Mahal.

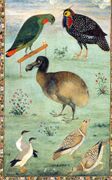

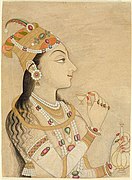

Painting, despite the Koranic prohibition, was also encouraged by the patronage of power. Akbar (unlettered, but whose library contained 24,000 illustrated manuscripts) founded Mughal painting in India by introducing painters such as Mir Saiyide Ali and Abdus Samad, who established pictorial schools in Gujarat, Rajasthan and Kashmir, characterized by formalism and lively, colorful ornamentation. Jahangir continued the patronage, but oriented the taste to a new realism focused on plants and animals, without interest in the human figure (painter Ustad Mansur).

In southern India, not subject to the Mogul Empire, the artistic tradition of ancient India continued, especially the culture of the Vijayanagara Empire, with capital in Hampi, and other rival states, such as Madurai.

To the northwest, in the Panjab area, a new religion began, Sikhism, which has in the Golden Temple its main artistic edifice.

- Indian architecture

Tomb of I'timād-ud-Daulah, Agra (1622-1628)

- Indian art

Central column of the Diwan-i-Khas (private courtroom) of the Akbar fort in Fatehpur Sikri (1569-1585)

Gopuram of the Meenakshi Ammán temple in Madurai (1559-1659)

Dodo, by Ustad Mansur (c. 1625)

Art from the Far East

Chinese art

The Forbidden City in Beijing was conceived by the architect Kuai Xiang (1397-1481). The construction of the gigantic complex began in 1406 and was completed in 1420. Its imperial palace is the largest wooden building in the world.

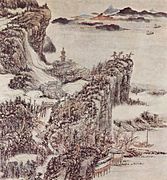

Prominent painters of the Ming dynasty (14th to 17th centuries) were Tang Yin, Wen Zhengming, Shen Zhou, Qiu Ying, Xu Wei or Dong Qichang. Prominent painters of the early Qin dynasty (18th century) were Bada Shanren, Shitao or Jiang Tingxi.[41]

- Chinese art

Ming Dynasty Porcelain.

Japanese art

The ancestral concept of beauty in Japan is linked to that of sabi (cycle of life and passage of time), and this did not change throughout the successive historical eras. To the centuries of the Early Modern Age corresponded the periods Muromachi Period (1336-1573), Azuchi-Momoyama (1568-1603) and Edo (1603-1868). Nevertheless, there were marked economic, social, political and ideological changes. The spread of Zen Buddhism added its taste for the small and everyday, synthesized in seven characteristics of profound artistic impact: asymmetry, simplicity, elegant austerity, naturalness, profound subtlety, freedom, and tranquility.

The sense of service to the community did not lead Japanese artists to the individualism of Western art, and apparently passes off the subtlest creations as little more than decorative art. Gardens, natural forms perfected by man, and calligraphy, the expression of manual gesture in ink on paper, were ideal vehicles for this particular expressiveness. Japanese Castles, Shintos, and Buddhist shrines are among the most important architectural forms, but even these large-scale constructions are characterized by the use of organic and ephemeral materials that need to be maintained and renewed over generations. The traumatic contact with the West from 1543 and the total closure to all outside contact in 1641 (sakoku) determined the continuity of Japanese artistic life through the evolution of its traditional models.[42]

- Japanese art

Calligraphy and representation of Bodhidarma, by Hakuin Ekaku (mid-18th century)

Filmography

- Andréi Rubliov (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966).

- The Agony and the Ecstasy (Carl Reed, 1965), on Michelangelo.

- El Greco (Iannis Smaragdis, 2007).

- Artemisia (Agnès Merlet, 1997), on Artemisia Gentileschi.

- Carnival in Flanders (Jaques Feyder, 1935), set in 17th century Netherlands.

- Rembrandt (Alexander Korda, 1936).

- Nightwatching (Peter Greenaway, 2007), on The Night Watch by Rembrandt.

- Girl with a Pearl Earring (Peter Webber, 2003), on the homonymous painting by Vermeer.

- The Dumbfounded King (Imanol Uribe, 1991, based on the novel by Gonzalo Torrente Ballester), set in mid-17th century Spain.

- Vatel (Roland Joffé, 2000), set in France at the end of the 17th century.

- The Draughtsman's Contract (Peter Greenaway, 1982), set in England in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

- Goya in Bordeaux (Carlos Saura, 1999), on Goya.[43]

See also

- Art

- History of art

- Art history

- Early modern period

- Ancien Régime

References

- ↑ History of french furniture, as cited in fr:Histoire du mobilier français and fr:Liste des styles de mobilier.

- ↑ Checa, Fernando. "Poder y piedad: patronos y mecenas en la introducción del Renacimiento en España" (in spanish). Reyes y mecenas. pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Stukembrok and Töpper (May 2, 2009). "The Working Stiff in Art: The Portinari Altarpiece". http://counterlightsrantsandblather1.blogspot.com/2009/05/working-stiff-in-art-portinari.html.

- ↑ Exhibition of the same name at Museo del Prado, 1998.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Grompone, Juan (in spanish). Albrecht Dürer en la historia del arte. pp. 31–32. http://www.grompone.org/ineditos/ciencia_y_tecnologia/Durero.pdf.

- ↑ "Pietro Cavallini in Naples". June 2009. http://faculty.ed.umuc.edu/~jmatthew/naples/Cavallini.htm.

- ↑ Martín González, op. cit. 108-120.

- ↑ The northern gates were built between 1401 and 1422 and the eastern gates, after a second commission, between 1425 and 1452.

- ↑ Renacimiento clásico. Artehistoria. (in Spanish)

- ↑ James William Pattison: The world’s painters since Leonardo; being a history of painting from the Renaissance to the present day. places this school in a timeframe between 1452 and 1564.

- ↑ Fernández, Barnechea and Haro, p. 236.

- ↑ Mannerism was initially defined in a pejorative way: as a decadent phase of the Renaissance, lacking in originality. Since the middle of the 20th century there has been a revaluation of the art of the period (1955 exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam organized by the Council of Europe) and Mannerism began to be defined as an autonomous style (Arnold Hauser, op. cit. and El manierismo, 1965). Sources cited by Fernández, Barnechea and Haro, op. cit., p. 263.

- ↑ Started by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger in 1514 with the 14th century criteria of the Florentine palace, Michelangelo continued the works between 1546-1549 and then Vignola and Giacomo della Porta until 1589. It is the model of the Roman palace of the Cinquecento.

- ↑ Martín González, op. cit, t. II, pp. 33-34

- ↑ The designations High Renaissance and Late Renaissance referring to Spain divide the 16th century into the two initial thirds (for the High, which would also include the last quarter of the century) in which the Catholic Monarchs (or Isabelline), Cisneros, Plateresque, and Purist (or Romanist) styles succeed one another; and the last third (for the Late), which is also described as Spanish Mannerism (see Fernández, Barnechea and Haro, op. cit). The periodization is different in other authors, giving definitions such as Serlian phase for the period 1530-1560 (by Sebastiano Serlio) and Classicist phase for the period 1560-1630 (José Miguel Muñoz Jiménez, El manierismo en la arquitectura española I and II). The discussion on the appropriateness of the Mannerist label for the Spanish case even leads to the use of terms such as anti-Mannerism, pseudo-Mannerism, counter-Mannerism or Trentino Mannerism. (Camón Aznar, quoted by Sviatoslav Savvatieyev A propósito del problema del manierismo en la pintura española Archived June 27, 2011 at Wayback Machine).

- ↑ Diego de Sagredo Las Medidas del Romano, 1526. In the Spain of the 1530s, the Roman prevailed over the modern, terms of the time that designated, respectively, the Renaissance and the Gothic, since it was considered that the former returned to Roman Antiquity and the latter was more current (Maroto, op. cit., p. 195).

- ↑ Since its characterization as a style by Heinrich Wölfflin, the definition of the baroque and its different phases has been subject to very different reinterpretations, even being seen as a phase of complication and crisis that would present all artistic styles (Eugenio D'Ors), while its initial denomination is unknown (it is usually related to the Portuguese word meaning 'irregular pearl' or to the Italian one meaning 'twisted reasoning', by a kind of false syllogism). The dates and phases, as well as the discernment between rococo and the final baroque are usually indicated very differently in art history manuals (see general bibliography; for example Palomero op. cit., p. 287). The denominations change for each country: for example, in Germany they speak of a high baroque or German baroque for the final period of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century (Fernández, Barnechea and Haro, op. cit., p. 287).

- ↑ Roma barroca. (in Spanish). Artehistoria.

- ↑ El arte en los centros periféricos Turín, urbanismo y arquitectura como afirmación política and Geometría y fantasía en la arquitectura de Guarini. (in Spanish). Artehistoria.

- ↑ Elliot, John H. (in Spanish). Un palacio para un rey. Taurus. ISBN 84-306-0524-X.

- ↑ In another Madrid square is the equestrian statue of Philip IV, by the same sculptor (1634-1640), made from sketches by Velázquez and with a daring posture, which famously required physical calculations by Galileo Galilei.

- ↑ La escultura francesa del siglo XVII. (in Spanish). Artehistoria.

- ↑ Fernández, Barnechea and Haro, op. cit., p. 343

- ↑ Conti, op.cit., p. 11

- ↑ Review of the exhibition at the National Archaeological Museum (2006).

- ↑ Conti, Flavio (1978) (in Spanish). Cómo reconocer el arte Rococó. Rizzoli. pp. 11–12. ISBN 84-85298-48-9.

- ↑ J. Palomo op. cit.; Conti, op. cit., p. 37

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 J. Maroto op. cit. p. 290-291.

- ↑ indiano n, adj. Spanish emigrant who became rich in Latin America. WordReference

- ↑ Gómez Piñol, Emilio (1991) (in Spanish). El arte indiano del siglo XVII: del orden visual clásico al "océano de colores". ISBN 84-205-2153-1.

- ↑ Los productos de la Sierra Negra, p. 41 (in Spanish)

- ↑ Espinosa spínola, G. (2004) El arte hispanoamericano: estado de la cuestión, (in Spanish) p. 11

- ↑ El mueble novohispano, (in Spanish) p. 22

- ↑ For the entire section: La Tercera Roma. (in Spanish). Artehistoria.

- ↑ Sullivan, Michael (1989). The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art. University of California Press. ISBN 978 0520059023.

- ↑ The use of earth and organic materials (wood, straw, and other fibers) as building materials, means that its current appearance is the result of constant maintenance and modification over the centuries.

- ↑ "کاخ گلستان". http://www.golestanpalace.ir/.

- ↑ Goody, Jack (1997). Representations and contradictions: ambivalence towards images, theatre, fiction, relics and sexuality.. Londres: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-20526-8.

- ↑ Grabar, Oleg (1987). Postscriptum, the formation of islamic art. Yale University. ISBN 0-300-03969-7.

- ↑ Allen, Terry (1988). "Aniconism and figural representation in islamic art". Five essays on islamic art. Occidental (CA): Solipsist. ISBN 0-944940-00-5.

- ↑ "Famous Ming Dynasty Painters and Galleries". https://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/.

- ↑ "La estética y el arte" (in spanish). http://www.artehistoria.jcyl.es/civilizaciones/contextos/8679.htm.

- ↑ For the entire section: Pintura y escultura en el cine (in Spanish)

Bibliography

- BARNECHEA, Emilio, FERNÁNDEZ, Antonio y HARO, Juan (1992) Historia del Arte, (in Spanish). Barcelona: Vicens Vives ISBN 84-316-2554-6

- BUSSAGLI, Marco, Comprender la arquitectura, (in Spanish). Madrid: Susaeta, ISBN 84-305-4483-6

- CHECA, Fernando y otros (1980) Guía para el estudio de la historia del arte, (in Spanish). Madrid: Cátedra, ISBN 84-376-0247-5

- CHILVERS, Ian; OSBORNE, Harold y FARR, Dennis (1992) Diccionario de Arte, (in Spanish). Madrid: Alianza, ISBN 84-206-524-8

- ECO, Umberto (2004) Historia de la Belleza, (in Spanish). Barcelona: Lumen ISBN 84-264-1468-0

- (2007) Historia de la Fealdad, (in Spanish). Barcelona: Lumen ISBN 978-84-264-1634-6

- GALLEGO, Raquel Historia del Arte, (in Spanish). Editex ISBN 978-84-9771-107-4

- GÓMEZ CACHO, X. y otros (2006) Nuevo Arterama. Historia del Arte, (in Spanish). Barcelona: Vicéns Vives, ISBN 84-316-7966-2

- Grupo Ágora Historia del Arte, (in Spanish). Akal, ISBN 84-460-1751-2

- MAROTO, J. Historia del Arte, (in Spanish). Casals, ISBN 978-84-218-4021-4

- MARTÍN GONZÁLEZ, Juan José (1974) Historia del Arte, (in Spanish). Madrid: Gredos (edición de 1992) ISBN 84-249-1022-2

- PALOMERO, Jesús Historia del Arte, (in Spanish). Algaida, 84-8433-085-0

- STUKENBROCK, Christiane y TÖPPER, Barbara (2000) 1000 obras maestras de la pintura europea del siglo XIII al XIX, (in Spanish). Könemann, ISBN 3-8290-2282-4

- Enciclopedias de Historia del Arte:

- - Summa Artis, Espasa Calpe.

- - Ars Magna, Planet