Helix

A helix (/ˈhiːlɪks/; pl. helices) is a shape like a corkscrew. It is a type of smooth space curve with tangent lines at a constant angle to a fixed axis. Helices are important in biology, as the DNA molecule is formed as two intertwined helices, and many proteins have helical substructures, known as alpha helices. The word helix comes from the Greek word ἕλιξ, "twisted, curved".[1] A "filled-in" helix – for example, a "spiral" (helical) ramp – is a surface called a helicoid.[2]

Properties and types

The pitch of a helix is the height of one complete helix turn, measured parallel to the axis of the helix.

A double helix consists of two (typically congruent) helices with the same axis, differing by a translation along the axis.[3]

A circular helix (i.e. one with constant radius) has constant band curvature and constant torsion.

A conic helix, also known as a conic spiral, may be defined as a spiral on a conic surface, with the distance to the apex an exponential function of the angle indicating direction from the axis.

A curve is called a general helix or cylindrical helix[4] if its tangent makes a constant angle with a fixed line in space. A curve is a general helix if and only if the ratio of curvature to torsion is constant.[5]

A curve is called a slant helix if its principal normal makes a constant angle with a fixed line in space.[6] It can be constructed by applying a transformation to the moving frame of a general helix.[7]

For more general helix-like space curves can be found, see space spiral; e.g., spherical spiral.

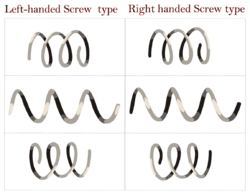

Handedness

Helices can be either right-handed or left-handed. With the line of sight along the helix's axis, if a clockwise screwing motion moves the helix away from the observer, then it is called a right-handed helix; if towards the observer, then it is a left-handed helix. Handedness (or chirality) is a property of the helix, not of the perspective: a right-handed helix cannot be turned to look like a left-handed one unless it is viewed in a mirror, and vice versa.

Mathematical description

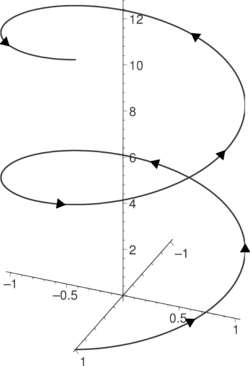

In mathematics, a helix is a curve in 3-dimensional space. The following parametrisation in Cartesian coordinates defines a particular helix;[8] perhaps the simplest equations for one is

As the parameter t increases, the point (x(t),y(t),z(t)) traces a right-handed helix of pitch 2π (or slope 1) and radius 1 about the z-axis, in a right-handed coordinate system.

In cylindrical coordinates (r, θ, h), the same helix is parametrised by:

A circular helix of radius a and slope a/b (or pitch 2πb) is described by the following parametrisation:

Another way of mathematically constructing a helix is to plot the complex-valued function exi as a function of the real number x (see Euler's formula). The value of x and the real and imaginary parts of the function value give this plot three real dimensions.

Except for rotations, translations, and changes of scale, all right-handed helices are equivalent to the helix defined above. The equivalent left-handed helix can be constructed in a number of ways, the simplest being to negate any one of the x, y or z components.

Arc length, curvature and torsion

A circular helix of radius a and slope a/b (or pitch 2πb) expressed in Cartesian coordinates as

has an arc length of

a curvature of

and a torsion of

A helix has constant non-zero curvature and torsion.

A helix is the vector-valued function

So a helix can be reparameterized as a function of s, which must be unit-speed:

The unit tangent vector is

The normal vector is

Its curvature is

.

The unit normal vector is

The binormal vector is

Its torsion is

Examples

An example of a double helix in molecular biology is the nucleic acid double helix.

An example of a conic helix is the Corkscrew roller coaster at Cedar Point amusement park.

Some curves found in nature consist of multiple helices of different handedness joined together by transitions known as tendril perversions.

Most hardware screw threads are right-handed helices. The alpha helix in biology as well as the A and B forms of DNA are also right-handed helices. The Z form of DNA is left-handed.

In music, pitch space is often modeled with helices or double helices, most often extending out of a circle such as the circle of fifths, so as to represent octave equivalency.

In aviation, geometric pitch is the distance an element of an airplane propeller would advance in one revolution if it were moving along a helix having an angle equal to that between the chord of the element and a plane perpendicular to the propeller axis; see also: pitch angle (aviation).

-

A natural left-handed helix, made by a climber plant

-

A charged particle in a uniform magnetic field following a helical path

-

A helical coil spring

See also

- Alpha helix

- Arc spring

- Boerdijk–Coxeter helix

- Circular polarization

- Collagen helix

- Helical symmetry

- Helicity

- Helix angle

- Helical axis

- Hemihelix

- Seashell surface

- Solenoid

- Superhelix

- Triple helix

References

- ↑ ἕλιξ , Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W.. "Helicoid". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Helicoid.html.

- ↑ "Double Helix " by Sándor Kabai, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- ↑ O'Neill, B. Elementary Differential Geometry, 1961 pg 72

- ↑ O'Neill, B. Elementary Differential Geometry, 1961 pg 74

- ↑ Izumiya, S. and Takeuchi, N. (2004) New special curves and developable surfaces. Turk J Math , 28:153–163.

- ↑ Menninger, T. (2013), An Explicit Parametrization of the Frenet Apparatus of the Slant Helix. arXiv:1302.3175 .

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W.. "Helix". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Helix.html.

- ↑ Schmitt, J.-L.; Stadler, A.-M.; Kyritsakas, N.; Lehn, J.-M. (2003). "Helicity-Encoded Molecular Strands: Efficient Access by the Hydrazone Route and Structural Features". Helvetica Chimica Acta 86: 1598–1624. doi:10.1002/hlca.200390137.

|

![Crystal structure of a folded molecular helix reported by Lehn et al.[9]](/wiki/images/thumb/0/05/Lehn_Beautiful_Foldamer_HelvChimActa_1598_2003.jpg/171px-Lehn_Beautiful_Foldamer_HelvChimActa_1598_2003.jpg)