Hyperbolic metric space

In mathematics, a hyperbolic metric space is a metric space satisfying certain metric relations (depending quantitatively on a nonnegative real number δ) between points. The definition, introduced by Mikhael Gromov, generalizes the metric properties of classical hyperbolic geometry and of trees. Hyperbolicity is a large-scale property, and is very useful to the study of certain infinite groups called Gromov-hyperbolic groups.

Definitions

In this paragraph we give various definitions of a -hyperbolic space. A metric space is said to be (Gromov-) hyperbolic if it is -hyperbolic for some .

Definition using the Gromov product

Let be a metric space. The Gromov product of two points with respect to a third one is defined by the formula:

Gromov's definition of a hyperbolic metric space is then as follows: is -hyperbolic if and only if all satisfy the four-point condition

Note that if this condition is satisfied for all and one fixed base point , then it is satisfied for all with a constant .[1] Thus the hyperbolicity condition only needs to be verified for one fixed base point; for this reason, the subscript for the base point is often dropped from the Gromov product.

Definitions using triangles

Up to changing by a constant multiple, there is an equivalent geometric definition involving triangles when the metric space is geodesic, i.e. any two points are end points of a geodesic segment (an isometric image of a compact subinterval of the reals). [2][3] [4] Note that the definition via Gromov products does not require the space to be geodesic.

Let . A geodesic triangle with vertices is the union of three geodesic segments (where denotes a segment with endpoints and ).

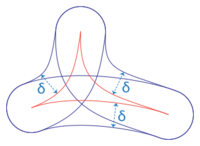

If for any point there is a point in at distance less than of , and similarly for points on the other edges, and then the triangle is said to be -slim .

A definition of a -hyperbolic space is then a geodesic metric space all of whose geodesic triangles are -slim. This definition is generally credited to Eliyahu Rips.

Another definition can be given using the notion of a -approximate center of a geodesic triangle: this is a point which is at distance at most of any edge of the triangle (an "approximate" version of the incenter). A space is -hyperbolic if every geodesic triangle has a -center.

These two definitions of a -hyperbolic space using geodesic triangles are not exactly equivalent, but there exists such that a -hyperbolic space in the first sense is -hyperbolic in the second, and vice versa.[5] Thus the notion of a hyperbolic space is independent of the chosen definition.

Examples

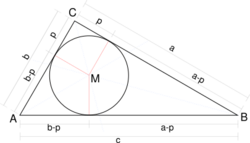

The hyperbolic plane is hyperbolic: in fact the incircle of a geodesic triangle is the circle of largest diameter contained in the triangle and every geodesic triangle lies in the interior of an ideal triangle, all of which are isometric with incircles of diameter 2 log 3.[6] Note that in this case the Gromov product also has a simple interpretation in terms of the incircle of a geodesic triangle. In fact the quantity (A,B)C is just the hyperbolic distance p from C to either of the points of contact of the incircle with the adjacent sides: for from the diagram c = (a – p) + (b – p), so that p = (a + b – c)/2 = (A,B)C.[7]

The Euclidean plane is not hyperbolic, for example because of the existence of homotheties.

Two "degenerate" examples of hyperbolic spaces are spaces with bounded diameter (for example finite or compact spaces) and the real line.

Metric trees and more generally real trees are the simplest interesting examples of hyperbolic spaces as they are 0-hyperbolic (i.e. all triangles are tripods).

The 1-skeleton of the triangulation by Euclidean equilateral triangles is not hyperbolic (it is in fact quasi-isometric to the Euclidean plane). A triangulation of the plane has a hyperbolic 1-skeleton if every vertex has degree 7 or more.

The two-dimensional grid is not hyperbolic (it is quasi-isometric to the Euclidean plane). It is the Cayley graph of the fundamental group of the torus; the Cayley graphs of the fundamental groups of a surface of higher genus is hyperbolic (it is in fact quasi-isometric to the hyperbolic plane).

Hyperbolicity and curvature

The hyperbolic plane (and more generally any Hadamard manifolds of sectional curvature ) is -hyperbolic. If we scale the Riemannian metric by a factor then the distances are multiplied by and thus we get a space that is -hyperbolic. Since the curvature is multiplied by we see that in this example the more (negatively) curved the space is, the lower the hyperbolicity constant.

Similar examples are CAT spaces of negative curvature. With respect to curvature and hyperbolicity it should be noted however that while curvature is a property that is essentially local, hyperbolicity is a large-scale property which does not see local (i.e. happening in a bounded region) metric phenomena. For example, the union of an hyperbolic space with a compact space with any metric extending the original ones remains hyperbolic.

Important properties

Invariance under quasi-isometry

One way to make precise the meaning of "large scale" is to require invariance under quasi-isometry. This is true of hyperbolicity.

- If a geodesic metric space is quasi-isometric to a -hyperbolic space then there exists such that is -hyperbolic.

The constant depends on and on the multiplicative and additive constants for the quasi-isometry.[8]

Approximate trees in hyperbolic spaces

The definition of an hyperbolic space in terms of the Gromov product can be seen as saying that the metric relations between any four points are the same as they would be in a tree, up to the additive constant . More generally the following property shows that any finite subset of an hyperbolic space looks like a finite tree.

- For any there is a constant such that the following holds: if are points in a -hyperbolic space there is a finite tree and an embedding such that for all and

The constant can be taken to be with and this is optimal.[9]

Exponential growth of distance and isoperimetric inequalities

In an hyperbolic space we have the following property:[10]

- There are such that for all with , every path joining to and staying at distance at least of has length at least .

Informally this means that the circumference of a "circle" of radius grows exponentially with . This is reminiscent of the isoperimetric problem in the Euclidean plane. Here is a more specific statement to this effect.[11]

- Suppose that is a cell complex of dimension 2 such that its 1-skeleton is hyperbolic, and there exists such that the boundary of any 2-cell contains at most 1-cells. Then there is a constant such that for any finite subcomplex we have

Here the area of a 2-complex is the number of 2-cells and the length of a 1-complex is the number of 1-cells. The statement above is a linear isoperimetric inequality; it turns out that having such an isoperimetric inequality characterises Gromov-hyperbolic spaces.[12] Linear isoperimetric inequalities were inspired by the small cancellation conditions from combinatorial group theory.

Quasiconvex subspaces

A subspace of a geodesic metric space is said to be quasiconvex if there is a constant such that any geodesic in between two points of stays within distance of .

- A quasi-convex subspace of an hyperbolic space is hyperbolic.

Asymptotic cones

All asymptotic cones of an hyperbolic space are real trees. This property characterises hyperbolic spaces.[13]

The boundary of a hyperbolic space

Generalising the construction of the ends of a simplicial tree there is a natural notion of boundary at infinity for hyperbolic spaces, which has proven very useful for analysing group actions.

In this paragraph is a geodesic metric space which is hyperbolic.

Definition using the Gromov product

A sequence is said to converge to infinity if for some (or any) point we have that as both and go to infinity. Two sequences converging to infinity are considered equivalent when (for some or any ). The boundary of is the set of equivalence classes of sequences which converge to infinity,[14] which is denoted .

If are two points on the boundary then their Gromov product is defined to be:

which is finite iff . One can then define a topology on using the functions .[15] This topology on is metrisable and there is a distinguished family of metrics defined using the Gromov product.[16]

Definition for proper spaces using rays

Let be two quasi-isometric embeddings of into ("quasi-geodesic rays"). They are considered equivalent if and only if the function is bounded on . If the space is proper then the set of all such embeddings modulo equivalence with its natural topology is homeomorphic to as defined above.[17]

A similar realisation is to fix a basepoint and consider only quasi-geodesic rays originating from this point. In case is geodesic and proper one can also restrict to genuine geodesic rays.

Examples

When is a simplicial regular tree the boundary is just the space of ends, which is a Cantor set. Fixing a point yields a natural distance on : two points represented by rays originating at are at distance .

When is the unit disk, i.e. the Poincaré disk model for the hyperbolic plane, the hyperbolic metric on the disk is

and the Gromov boundary can be identified with the unit circle.

The boundary of -dimensional hyperbolic space is homeomorphic to the -dimensional sphere and the metrics are similar to the one above.

Busemann functions

If is proper then its boundary is homeomorphic to the space of Busemann functions on modulo translations.[18]

The action of isometries on the boundary and their classification

A quasi-isometry between two hyperbolic spaces induces a homeomorphism between the boundaries.

In particular the group of isometries of acts by homeomorphisms on . This action can be used[19] to classify isometries according to their dynamical behaviour on the boundary, generalising that for trees and classical hyperbolic spaces. Let be an isometry of , then one of the following cases occur:

- First case: has a bounded orbit on (in case is proper this implies that has a fixed point in ). Then it is called an elliptic isometry.

- Second case: has exactly two fixed points on and every positive orbit accumulates only at . Then is called an hyperbolic isometry.

- Third case: has exactly one fixed point on the boundary and all orbits accumulate at this point. Then it is called a parabolic isometry.

More examples

Subsets of the theory of hyperbolic groups can be used to give more examples of hyperbolic spaces, for instance the Cayley graph of a small cancellation group. It is also known that the Cayley graphs of certain models of random groups (which is in effect a randomly-generated infinite regular graph) tend to be hyperbolic very often.

It can be difficult and interesting to prove that certain spaces are hyperbolic. For example, the following hyperbolicity results have led to new phenomena being discovered for the groups acting on them.

- The hyperbolicity of the curve complex[20] has led to new results on the mapping class group.[21]

- Similarly, the hyperbolicity of certain graphs[22] associated to the outer automorphism group Out(Fn) has led to new results on this group.

See also

- Negatively curved group

- Ideal triangle

Notes

- ↑ Coornaert, Delzant & Papadopoulos 1990, pp. 2–3

- ↑ de la Harpe & Ghys 1990, Chapitre 2, Proposition 21.

- ↑ Bridson & Haefliger 1999, Chapter III.H, Proposition 1.22.

- ↑ Coornaert, Delzant & Papadopoulos 1990, pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Bridson & Haefliger 1999, Chapter III.H, Proposition 1.17.

- ↑ Coornaert, Delzant & Papadopoulos 1990, pp. 11–12

- ↑ Coornaert, Delzant & Papadopoulos 1990, p. 1–2s

- ↑ de la Harpe & Ghys 1990, Chapitre 5, Proposition 15.

- ↑ Bowditch 2006, Chapter 6.4.

- ↑ Bridson & Haefliger 1999, Chapter III.H, Proposition 1.25.

- ↑ a more general statement is given in (Bridson Haefliger)

- ↑ Bridson & Haefliger 1999, Chapter III.H, Theorem 2.9.

- ↑ Dyubina (Erschler), Anna; Polterovich, Iosif (2001). "Explicit constructions of universal R-trees and asymptotic geometry of hyperbolic spaces". Bull. London Math. Soc. 33: pp. 727–734.

- ↑ de la Harpe & Ghys 1990, Chapitre 7, page 120.

- ↑ de la Harpe & Ghys 1990, Chapitre 7, section 2.

- ↑ de la Harpe & Ghys 1990, Chapitre 7, section 3.

- ↑ de la Harpe & Ghys 1990, Chapitre 7, Proposition 4.

- ↑ Bridson & Haefliger 1999, p. 428.

- ↑ de la Harpe & Ghys 1990, Chapitre 8.

- ↑ Masur, Howard A.; Minsky, Yair N. (1999). "Geometry of the complex of curves. I. Hyperbolicity". Invent. Math. 138: pp. 103–149. doi:10.1007/s002220050343.

- ↑ Dahmani, François; Guirardel, Vincent; Osin, Denis (2017). "Hyperbolically embedded subgroups and rotating families in groups acting on hyperbolic spaces". Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society 245 (1156). doi:10.1090/memo/1156.

- ↑ Bestvina, Mladen; Feighn, Mark (2014). "Hyperbolicity of the complex of free factors". Advances in Mathematics 256: 104–155. doi:10.1016/j.aim.2014.02.001.

References

- Bowditch, Brian (2006), A course on geometric group theory, Mat. soc. Japan, http://www.warwick.ac.uk/~masgak/papers/bhb-ggtcourse.pdf

- Bridson, Martin R.; Haefliger, André (1999), Metric spaces of non-positive curvature, Springer

- Coornaert, M.; Delzant, T.; Papadopoulos, A. (1990) (in fr), Géométrie et théorie des groupes. Les groupes hyperboliques de Gromov, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 1441, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-52977-2

- de la Harpe, Pierre; Ghys, Etienne (1990) (in fr), Sur les groupes hyperboliques d'après Mikhael Gromov, Birkhäuser

- Gromov, Mikhael (1987), "Hyperbolic groups", in Gersten, S.M., Essays in group theory, Springer, pp. 75–264

- Roe, John (2003), Lectures on Coarse Geometry, University Lecture Series, 31, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-3332-2

- Väisälä, Jussi (2005), "Gromov hyperbolic spaces", Expositiones Mathematicae 23 (3): 187–231, doi:10.1016/j.exmath.2005.01.010.

|