Inscribed angle

In geometry, an inscribed angle is the angle formed in the interior of a circle when two chords intersect on the circle. It can also be defined as the angle subtended at a point on the circle by two given points on the circle.

Equivalently, an inscribed angle is defined by two chords of the circle sharing an endpoint.

The inscribed angle theorem relates the measure of an inscribed angle to that of the central angle intercepting the same arc.

The inscribed angle theorem appears as Proposition 20 in Book 3 of Euclid's Elements.

Note that this theorem is not to be confused with the Angle bisector theorem, which also involves angle bisection (but of an angle of a triangle not inscribed in a circle).

Theorem

Statement

The inscribed angle theorem states that an angle θ inscribed in a circle is half of the central angle 2θ that intercepts the same arc on the circle. Therefore, the angle does not change as its vertex is moved to different positions on the same arc of the circle.

Proof

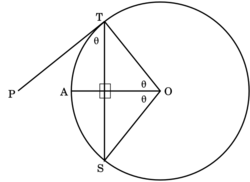

Inscribed angles where one chord is a diameter

Let O be the center of a circle, as in the diagram at right. Choose two points on the circle, and call them V and A. Designate point B to be diametrically opposite point V. Draw chord VB, a diameter containing point O. Draw chord VA. Angle ∠BVA is an inscribed angle that intercepts arc Template:Overarc; denote it as ψ. Draw line OA. Angle ∠BOA is a central angle that also intercepts arc Template:Overarc; denote it as θ.

Lines OV and OA are both radii of the circle, so they have equal lengths. Therefore, triangle △VOA is isosceles, so angle ∠BVA and angle ∠VAO are equal.

Angles ∠BOA and ∠AOV are supplementary, summing to a straight angle (180°), so angle ∠AOV measures 180° − θ.

The three angles of triangle △VOA must sum to 180°:

Adding to both sides yields

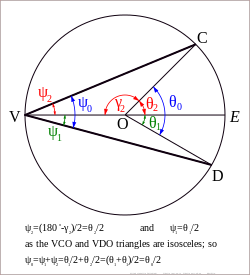

Inscribed angles with the center of the circle in their interior

Given a circle whose center is point O, choose three points V, C, D on the circle. Draw lines VC and VD: angle ∠DVC is an inscribed angle. Now draw line OV and extend it past point O so that it intersects the circle at point E. Angle ∠DVC intercepts arc Template:Overarc on the circle.

Suppose this arc includes point E within it. Point E is diametrically opposite to point V. Angles ∠DVE, ∠EVC are also inscribed angles, but both of these angles have one side which passes through the center of the circle, therefore the theorem from the above Part 1 can be applied to them.

Therefore,

then let

so that

Draw lines OC and OD. Angle ∠DOC is a central angle, but so are angles ∠DOE and ∠EOC, and

Let

so that

From Part One we know that and that . Combining these results with equation (2) yields

therefore, by equation (1),

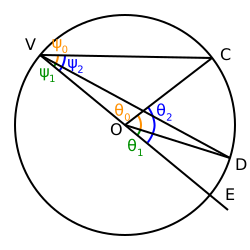

Inscribed angles with the center of the circle in their exterior

The previous case can be extended to cover the case where the measure of the inscribed angle is the difference between two inscribed angles as discussed in the first part of this proof.

Given a circle whose center is point O, choose three points V, C, D on the circle. Draw lines VC and VD: angle ∠DVC is an inscribed angle. Now draw line OV and extend it past point O so that it intersects the circle at point E. Angle ∠DVC intercepts arc Template:Overarc on the circle.

Suppose this arc does not include point E within it. Point E is diametrically opposite to point V. Angles ∠EVD, ∠EVC are also inscribed angles, but both of these angles have one side which passes through the center of the circle, therefore the theorem from the above Part 1 can be applied to them.

Therefore,

then let

so that

Draw lines OC and OD. Angle ∠DOC is a central angle, but so are angles ∠EOD and ∠EOC, and

Let

so that

From Part One we know that and that . Combining these results with equation (4) yields therefore, by equation (3),

Corollary

By a similar argument, the angle between a chord and the tangent line at one of its intersection points equals half of the central angle subtended by the chord. See also Tangent lines to circles.

Applications

2𝜃 + 2𝜙 = 360° ∴ 𝜃 + 𝜙 = 180°

The inscribed angle theorem is used in many proofs of elementary Euclidean geometry of the plane. A special case of the theorem is Thales's theorem, which states that the angle subtended by a diameter is always 90°, i.e., a right angle. As a consequence of the theorem, opposite angles of cyclic quadrilaterals sum to 180°; conversely, any quadrilateral for which this is true can be inscribed in a circle. As another example, the inscribed angle theorem is the basis for several theorems related to the power of a point with respect to a circle. Further, it allows one to prove that when two chords intersect in a circle, the products of the lengths of their pieces are equal.

Inscribed angle theorems for ellipses, hyperbolas and parabolas

Inscribed angle theorems exist for ellipses, hyperbolas and parabolas too. The essential differences are the measurements of an angle. (An angle is considered a pair of intersecting lines.)

References

- Ogilvy, C. S. (1990). Excursions in Geometry. Dover. pp. 17–23. ISBN 0-486-26530-7.

- The VNR Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. 1977. pp. 172. ISBN 0-442-22646-2.

- Moise, Edwin E. (1974). Elementary Geometry from an Advanced Standpoint (2nd ed.). Reading: Addison-Wesley. pp. 192–197. ISBN 0-201-04793-4.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Inscribed Angle". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/InscribedAngle.html.

- Relationship Between Central Angle and Inscribed Angle

- Munching on Inscribed Angles at cut-the-knot

- Arc Central Angle With interactive animation

- Arc Peripheral (inscribed) Angle With interactive animation

- Arc Central Angle Theorem With interactive animation

- At bookofproofs.github.io

|