Interval contractor

In mathematics, an interval contractor (or contractor for short)[1] associated to a set is an operator which associates to a hyperrectangle in another box of such that the two following properties are always satisfied:

- (contractance property)

- (completeness property)

A contractor associated to a constraint (such as an equation or an inequality) is a contractor associated to the set of all which satisfy the constraint. Contractors make it possible to improve the efficiency of branch-and-bound algorithms classically used in interval analysis.

Properties of contractors

A contractor C is monotonic if we have .

It is minimal if for all boxes [x], we have , where [A] is the interval hull of the set A, i.e., the smallest box enclosing A.

The contractor C is thin if for all points x, where {x} denotes the degenerated box enclosing x as a single point.

The contractor C is idempotent if for all boxes [x], we have

The contractor C is convergent if for all sequences [x](k) of boxes containing x, we have

Illustration

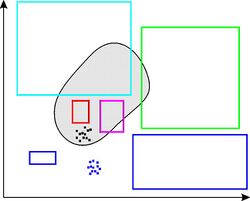

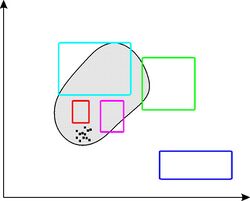

Figure 1 represents the set X painted grey and some boxes, some of them degenerated (i.e., they correspond to singletons). Figure 2 represents these boxes after contraction. Note that no point of X has been removed by the contractor. The contractor is minimal for the cyan box but is pessimistic for the green one. All degenerated blue boxes are contracted to the empty box. The magenta box and the red box cannot be contracted.

Contractor algebra

Some operations can be performed on contractors to build more complex contractors. [2] The intersection, the union, the composition and the repetition are defined as follows.

Building contractors

There exist different ways to build contractors associated to equations and inequalities, say, f(x) in [y]. Most of them are based on interval arithmetic. One of the most efficient and most simple is the forward/backward contractor (also called as HC4-revise).[3][4]

The principle is to evaluate f(x) using interval arithmetic (this is the forward step). The resulting interval is intersected with [y]. A backward evaluation of f(x) is then performed in order to contract the intervals for the xi (this is the backward step). We now illustrate the principle on a simple example.

Consider the constraint We can evaluate the function f(x) by introducing the two intermediate variables a and b, as follows

The two previous constraints are called forward constraints. We get the backward constraints by taking each forward constraint in the reverse order and isolating each variable on the right hand side. We get

The resulting forward/backward contractor is obtained by evaluating the forward and the backward constraints using interval analysis.

References

- ↑ Jaulin, Luc; Kieffer, Michel; Didrit, Olivier; Walter, Eric (2001). Applied Interval Analysis. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 1-85233-219-0.

- ↑ Chabert, G.; Jaulin, L. (2009). "Contractor programming". Artificial Intelligence 173 (11): 1079–1100. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2009.03.002. http://www.ensta-bretagne.fr/jaulin/paper_chabert_quimper.pdf.

- ↑ Messine, F. (1997). Méthode d'optimisation globale basée sur l'analyse d'intervalles pour la résolution de problèmes avec contraintes. Thèse de doctorat, Institut National Polytechnique de Toulouse. http://messine.perso.enseeiht.fr/PUBLIS/these.ps.

- ↑ Benhamou, F.; Goualard, F.; Granvilliers, L.; Puget, J.F. (1999). Revising hull and box consistency. In Proceedings of the 1999 international conference on Logic programming. https://frederic.goualard.net/publications/revising-hull-and-box-consistency_benhamou_et-al_iclp1999.pdf.

|