Union (set theory)

In set theory, the union (denoted by ∪) of a collection of sets is the set of all elements in the collection.[1] It is one of the fundamental operations through which sets can be combined and related to each other. A nullary union refers to a union of zero () sets and it is by definition equal to the empty set.

For explanation of the symbols used in this article, refer to the table of mathematical symbols.

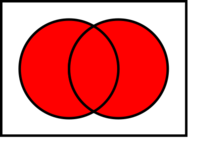

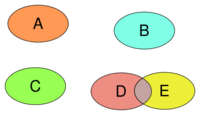

Union of two sets

The union of two sets A and B is the set of elements which are in A, in B, or in both A and B.[2] In set-builder notation,

- .[3]

For example, if A = {1, 3, 5, 7} and B = {1, 2, 4, 6, 7} then A ∪ B = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7}. A more elaborate example (involving two infinite sets) is:

- A = {x is an even integer larger than 1}

- B = {x is an odd integer larger than 1}

As another example, the number 9 is not contained in the union of the set of prime numbers {2, 3, 5, 7, 11, ...} and the set of even numbers {2, 4, 6, 8, 10, ...}, because 9 is neither prime nor even.

Sets cannot have duplicate elements,[3][4] so the union of the sets {1, 2, 3} and {2, 3, 4} is {1, 2, 3, 4}. Multiple occurrences of identical elements have no effect on the cardinality of a set or its contents.

Algebraic properties

Binary union is an associative operation; that is, for any sets

Thus, the parentheses may be omitted without ambiguity: either of the above can be written as Also, union is commutative, so the sets can be written in any order.[5] The empty set is an identity element for the operation of union. That is, for any set Also, the union operation is idempotent: All these properties follow from analogous facts about logical disjunction.

Intersection distributes over union and union distributes over intersection[2]

The power set of a set together with the operations given by union, intersection, and complementation, is a Boolean algebra. In this Boolean algebra, union can be expressed in terms of intersection and complementation by the formula where the superscript denotes the complement in the universal set

Finite unions

One can take the union of several sets simultaneously. For example, the union of three sets A, B, and C contains all elements of A, all elements of B, and all elements of C, and nothing else. Thus, x is an element of A ∪ B ∪ C if and only if x is in at least one of A, B, and C.

A finite union is the union of a finite number of sets; the phrase does not imply that the union set is a finite set.[6][7]

Arbitrary unions

The most general notion is the union of an arbitrary collection of sets, sometimes called an infinitary union. If M is a set or class whose elements are sets, then x is an element of the union of M if and only if there is at least one element A of M such that x is an element of A.[8] In symbols:

This idea subsumes the preceding sections—for example, A ∪ B ∪ C is the union of the collection {A, B, C}. Also, if M is the empty collection, then the union of M is the empty set.

Notations

The notation for the general concept can vary considerably. For a finite union of sets one often writes or . Various common notations for arbitrary unions include , , and . The last of these notations refers to the union of the collection , where I is an index set and is a set for every . In the case that the index set I is the set of natural numbers, one uses the notation , which is analogous to that of the infinite sums in series.[8]

When the symbol "∪" is placed before other symbols (instead of between them), it is usually rendered as a larger size.

Notation encoding

In Unicode, union is represented by the character U+222A ∪ UNION.[9] In TeX, is rendered from \cup and is rendered from \bigcup.

See also

- Algebra of sets – Identities and relationships involving sets

- Alternation (formal language theory) − the union of sets of strings

- Axiom of union – Concept in axiomatic set theory

- Disjoint union – In mathematics, operation on sets

- Inclusion–exclusion principle – Counting technique in combinatorics

- Intersection (set theory) – Set of elements common to all of some sets

- Iterated binary operation – Repeated application of an operation to a sequence

- List of set identities and relations – Equalities for combinations of sets

- Naive set theory – Informal set theories

- Symmetric difference – Elements in exactly one of two sets

Notes

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Union". Wolfram Mathworld. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Union.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Set Operations | Union | Intersection | Complement | Difference | Mutually Exclusive | Partitions | De Morgan's Law | Distributive Law | Cartesian Product". https://www.probabilitycourse.com/chapter1/1_2_2_set_operations.php.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Vereshchagin, Nikolai Konstantinovich; Shen, Alexander (2002-01-01) (in en). Basic Set Theory. American Mathematical Soc.. ISBN 9780821827314. https://books.google.com/books?id=LBvpfEMhurwC.

- ↑ deHaan, Lex; Koppelaars, Toon (2007-10-25) (in en). Applied Mathematics for Database Professionals. Apress. ISBN 9781430203483. https://books.google.com/books?id=2hM3-xxZC-8C&pg=PA24.

- ↑ Halmos, P. R. (2013-11-27) (in en). Naive Set Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781475716450. https://books.google.com/books?id=jV_aBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Dasgupta, Abhijit (2013-12-11) (in en). Set Theory: With an Introduction to Real Point Sets. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781461488545. https://books.google.com/books?id=u06-BAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ "Finite Union of Finite Sets is Finite". https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Finite_Union_of_Finite_Sets_is_Finite.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Smith, Douglas; Eggen, Maurice; Andre, Richard St (2014-08-01) (in en). A Transition to Advanced Mathematics. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781285463261. https://archive.org/details/transitiontoadva0000smit.

- ↑ "The Unicode Standard, Version 15.0 - Mathematical Operators - Range: 2200–22FF". p. 3. https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U2200.pdf.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Union of sets", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/u095390

- Infinite Union and Intersection at ProvenMath De Morgan's laws formally proven from the axioms of set theory.

|