Kadir–Brady saliency detector

| Feature detection |

|---|

| Edge detection |

| Corner detection |

| Blob detection |

| Ridge detection |

| Hough transform |

| Structure tensor |

| Affine invariant feature detection |

| Feature description |

| Scale space |

The Kadir–Brady saliency detector extracts features of objects in images that are distinct and representative. It was invented by Timor Kadir and J. Michael Brady[1] in 2001 and an affine invariant version was introduced by Kadir and Brady in 2004[2] and a robust version was designed by Shao et al.[3] in 2007.

The detector uses the algorithms to more efficiently remove background noise and so more easily identify features which can be used in a 3D model. As the detector scans images it uses the three basics of global transformation, local perturbations and intra-class variations to define the areas of search, and identifies unique regions of those images rather than using the more traditional corner or blob searches. It attempts to be invariant to affine transformations and illumination changes.[4]

This leads to a more object oriented search than previous methods and outperforms other detectors due to non blurring of the images, an ability to ignore slowly changing regions and a broader definition of surface geometry properties. As a result, the Kadir–Brady saliency detector is more capable at object recognition than other detectors whose main focus is on whole image correspondence.

Introduction

Many computer vision and image processing applications work directly with the features extracted from an image, rather than the raw image; for example, for computing image correspondences, or for learning object categories. Depending on the applications, different characteristics are preferred. However, there are three broad classes of image change under which good performance may be required:

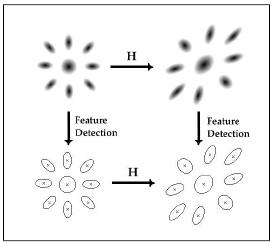

Global transformation: Features should be repeatable across the expected class of global image transformations. These include both geometric and photometric transformations that arise due to changes in the imaging conditions. For example, region detection should be covariant with viewpoint as illustrated in Figure 1. In short, we require the segmentation to commute with viewpoint change. This property will be evaluated on the repeatability and accuracy of localization and region estimation.

Local perturbations: Features should be insensitive to classes of semi-local image disturbances. For example, a feature responding to the eye of a human face should be unaffected by any motion of the mouth. A second class of disturbance is where a region neighbours a foreground/background boundary. The detector can be required to detect the foreground region despite changes in the background.

Intra-class variations: Features should capture corresponding object parts under intra-class variations in objects. For example, the headlight of a car for different brands of car (imaged from the same viewpoint).

All Feature detection algorithms attempt to detect regions which are stable under the three types of image change described above. Instead of finding a corner, or blob, or any specific shape of region, the Kadir–Brady saliency detector looks for regions which are locally complex, and globally discriminative. Such regions usually correspond to regions more stable under these types of image change.

Information-theoretic saliency

In the field of Information theory Shannon entropy is defined to quantify the complexity of a distribution p as [math]\displaystyle{ p \log p \, }[/math]. Therefore, higher entropy means p is more complex hence more unpredictable.

To measure the complexity of an image region [math]\displaystyle{ \{x,R\} }[/math] around point [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] with shape [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math], a descriptor [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math] that takes on values [math]\displaystyle{ {d_1 ,\dots , d_r } }[/math] (e.g., in an 8 bit grey level image, D would range from 0 to 255 for each pixel) is defined so that [math]\displaystyle{ P_{D}(d_i,x,R) }[/math], the probability of descriptor value [math]\displaystyle{ d_i }[/math] occurs in region [math]\displaystyle{ \{x,R\} }[/math] can be computed. Further, the entropy of image region [math]\displaystyle{ R_x }[/math] can compute as

- [math]\displaystyle{ H_{D}(x,R) = -\sum_{i \in (1\dots r)} P_{D}(d_i,x,R) \log P_{D}(d_i,x,R). }[/math]

Using this entropy equation we can further calculate [math]\displaystyle{ H_{D}(x,R) }[/math] for every point [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and region shape [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math]. A more complex region, like the eye region, has a more complex distributor and hence higher entropy.

[math]\displaystyle{ H_{D}(x,R) }[/math] is a good measure for local complexity. Entropy only measures the statistic of the local attribute. It does not measure the spatial arrangement of the local attribute. However, these four regions are not equally discriminative under scale change. This observation is used to define measure on discriminative in subsections.

The following subsections will discuss different methods to select regions with high local complexity and greater discrimination between different regions.

Similarity-invariant saliency

The first version of the Kadir–Brady saliency detector[10] only finds Salient regions invariant under similarity transformation. The algorithm finds circle regions with different scales. In other words, given [math]\displaystyle{ H_{D}(x,s) }[/math], where s is the scale parameter of a circle region [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math], the algorithm selects a set of circle regions, [math]\displaystyle{ \{x_i,s_i;i=1\dots N\} }[/math].

The method consists of three steps:

- Calculation of Shannon entropy of local image attributes for each x over a range of scales — [math]\displaystyle{ H_{D}(x,s) = -\sum_{i \in (1\dots r)} P_{D}(d_i,x,s) \log P_{D}(d_i,x,s)/10 }[/math];

- Select scales at which the entropy over scale function exhibits a peak — [math]\displaystyle{ s_p }[/math] ;

- Calculate the magnitude change of the PDF as a function of scale at each peak — [math]\displaystyle{ W_D(x,s) = \sum_{i \in (1\dots r)} |\frac{\partial}{\partial s}P_{D,}(d_i,x,s)| }[/math] (s).

The final saliency [math]\displaystyle{ Y_D(x,s_p) }[/math] is the product of [math]\displaystyle{ H_D(x,s_p) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ W_D(x,s_p) }[/math].

For each x the method picks a scale [math]\displaystyle{ s_p }[/math] and calculates salient score [math]\displaystyle{ Y_D(x,s_p) }[/math]. By comparing [math]\displaystyle{ Y_D(x,s_p) }[/math] of different points [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] the detector can rank the saliency of points and pick the most representative ones.

Affine-invariant saliency

Previous method is invariant to the similarity group of geometric transformations and to photometric shifts. However, as mentioned in the opening remarks, the ideal detector should detect region invariant up to viewpoint change. There are several detector [] can detect affine invariant region which is a better approximation of viewpoint change than similarity transformation.

To detect affine invariant region, the detector need to detect ellipse as in figure 4. [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] now is parameterized by three parameter (s, "ρ", "θ"), where "ρ" is the axis ratio and "θ" the orientation of the ellipse.

This modification increases the search space of the previous algorithm from a scale to a set of parameters and therefore the complexity of the affine invariant saliency detector increases. In practice the affine invariant saliency detector starts with the set of points and scales generated from the similarity invariant saliency detector then iteratively approximates the suboptimal parameters.

Comparison

Although similarity invariant saliency detector is faster than Affine invariant saliency detector it also has the drawback of favoring isotropic structure, since the discriminative measure [math]\displaystyle{ W_D }[/math] is measured over isotropic scale.

To summarize: Affine invariant saliency detector is invariant to affine transformation and able to detect more generate salient regions.

Salient volume

It is intuitive to pick points from a higher salient score directly and stop when a certain number of threshold on "number of points" or "salient score" is satisfied. Natural images contain noise and motion blur which both act as randomisers and generally increase entropy, affecting previously low entropy values more than high entropy values.

A more robust method would be to pick regions rather than points in entropy space. Although the individual pixels within a salient region may be affected at any given instant, by the noise, it is unlikely to affect all of them in such a way that the region as a whole becomes non-salient.

It is also necessary to analyze the whole saliency space such that each salient feature is represented. A global threshold approach would result in highly salient features in one part of the image dominating the rest. A local threshold approach would require the setting of another scale parameter.

A simple clustering algorithm meets these two requirements are used at the end of the algorithm. It works by selecting highly salient points that have local support i.e. nearby points with similar saliency and scale. Each region must be sufficiently distant from all others (in R3) to qualify as a separate entity. For robustness we use a representation that includes all of the points in a selected region. The method works as follows:

- Apply a global threshold.

- Choose the highest salient point in saliency-space (Y).

- Find the K nearest neighbours (K is a pre-set constant).

- Test the support of these using variance of the centre points.

- Find distance, D, in R3 from salient regions already clustered.

- Accept, if D > scalemean of the region and if sufficiently clustered (variance is less than pre-set threshold Vth ).

- Store as the mean scale and spatial location of K points.

- Repeat from step 2 with next highest salient point.

The algorithm is implemented as GreedyCluster1.m in matlab by Dr. Timor Kadir[5]

Performance evaluation

In the field of computer vision different feature detectors have been evaluated by several tests. The most profound evaluation is published in the International Journal of Computer Vision in 2006.[6] The following subsection discuss the performance of Kadir–Brady saliency detector on a subset of a test in the paper.

Performance under global transformation

In order to measure the consistency of a region detected on the same object or scene across images under global transformation, repeatability score, which is first proposed by Mikolajczyk and Cordelia Schmid in [18, 19] is calculated as follows:[7][8]

Firstly, overlap error [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math] of a pair of corresponding ellipses [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_b }[/math] each on different images is defined:

[math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon = 1 - \frac{\mu_a \cap (A^T \mu_b A)}{\mu_a \cup (A^T \mu_b A)} }[/math]

where A is the locally linearized affine transformation of the homography between the two images,

and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_a \cap (A^T \mu_b A) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_a \cup (A^T \mu_b A) }[/math] represent the area of intersection and union of the ellipses respectively.

Notice [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_a }[/math] is scaled into a fix scale to take the count of size variation of different detected region. Only if [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math] is smaller than certain [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon_0 }[/math], the pair of ellipses are deemed to correspond.

Then the repeatability score for a given pair of images is computed as the ratio between the number of region-to-region correspondences and the smaller of the number of regions in the pair of images, where only the regions located in the part of the scene present in both images are counted. In general we would like a detector to have a high repeatability score and a large number of correspondences.

The specific global transformations tested in the test dataset are:

- Viewpoint change

- Zoom+rotation

- Image blur

- JPEG compression

- Light change

The performance of Kadir–Brady saliency detector is inferior to most of other detectors mainly because the number of points detected is usually lower than other detectors.

The precise procedure is given in the Matlab code from Detector evaluation

- Software implementation.

Performance under intra-class variation and image perturbations

In the task of object class categorization, the ability of detecting similar regions given intra-class variation and image perturbations across object instance is very critical. Repeatability measures over intra-class variation and image perturbations is proposed. The following subsection will introduce the definition and discuss the performance.

Intra-class variation test

Suppose there are a set of images of the same object class e.g., motorbikes. A region detection operator which is unaffected by intra-class variation will reliably select regions on corresponding parts of all the objects — say the wheels, engine or seat for motorbikes.

Repeatability over intra-class variation is measuring the (average) number of correct correspondences over the set of images, where the correct correspondences is established by manual selection.

A region is matched if it fulfills three requirements:

- Its position matches within 10 pixels.

- Its scale is within 20%.

- Normalized mutual information between the appearances is > 0.4.

In detail the average correspondence score S is measured as follows.

N regions are detected on each image of the M images in the dataset. Then for a particular reference image, i, the correspondence score [math]\displaystyle{ S_i }[/math] is given by the proportion of corresponding to detected regions for all the other images in the dataset, i.e.:

[math]\displaystyle{ Si = \frac{\text{Total number of matches}}{\text{Total number of detected regions}}=\frac{N_{M}^{i}}{N (M-1)} }[/math]

The score[math]\displaystyle{ S_i }[/math] is computed for M/2 different selections of the reference image and averaged to give S. The score is evaluated as a function of the number of detected regions N.

The Kadir–Brady saliency detector gives the highest score across three test classes which are motorbike, car and face. The saliency detector indicates that most detections are near the object. In contrast, other detectors maps show a much more diffuse pattern over the entire area caused by poor localization and false responses to background clutter.

Image perturbations test

In order to test insensitivity to image perturbation the data set is split into two parts: the first contains images with a uniform background and the second images with varying degrees of background clutter. If the detector is robust to background clutter then the average correspondence score S should be similar for both subsets of images.

In this test saliency detector also outperforms other detectors due to three reasons:

- Several detection methods blur the image, hence causing a greater degree of similarity between objects and background.

- In most images the objects of interest tend to be in focus while backgrounds are out of focus and hence blurred. Blurred regions tend to exhibit slowly varying statistics which result in a relatively low entropy and inter-scale saliency in the saliency detector.

- Other detectors define saliency with respect to specific properties of the local surface geometry. In contrast the saliency detector uses a much broader definition.

The saliency detector is most useful in the task of object recognition, whereas several other detectors are more useful in the task of computing image correspondences. However, in the task of 3D object recognition where all three types of image change are combined, saliency detector might still be powerful.[citation needed]

Software implementation

- Scale Saliency and Scale Descriptors by Timor Kadir

- Affine Invariant Scale Saliency by Timor Kadir

- Comparison of Affine Region Detectors

References

- ↑ Kadir, Timor; Zisserman, Andrew; Brady, Michael (2004). "An Affine Invariant Salient Region Detector". Computer Vision - ECCV 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 3021. pp. 228–241. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-24670-1_18. ISBN 978-3-540-21984-2.

- ↑ Zisserman, A.

- ↑ Ling Shao, Timor Kadir and Michael Brady. Geometric and Photometric Invariant Distinctive Regions Detection. Information Sciences. 177 (4):1088-1122, 2007 doi:10.1016/j.ins.2006.09.003

- ↑ W. Li; G. Bebis; N. G. Bourbakis (2008). "3-D Object Recognition Using 2-D Views". IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 17 (11): 2236–2255. doi:10.1109/tip.2008.2003404. PMID 18854254. Bibcode: 2008ITIP...17.2236L.

- ↑ [1] Kadir,T GreedyCluster1.m download

- ↑ A comparison of affine region detectors. K. Mikolajczyk, T. Tuytelaars, C. Schmid, A. Zisserman, J. Matas, F. Schaffalitzky, T. Kadir and L. Van Gool. International Journal of Computer Vision

- ↑ [2] Mikolajczyk

- ↑ [3] Schmid, C

Further reading

- A. Baumberg (2000). "Reliable feature matching across widely separated views". pp. I:1774–1781. http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/baumberg00reliable.html.

- T. Lindeberg (1998). "Feature detection with automatic scale selection" (abstract). International Journal of Computer Vision 30 (2): 77–116. doi:10.1023/A:1008045108935. http://www.nada.kth.se/cvap/abstracts/cvap198.html.(scale-adaptive and scale invariant interest points from Laplacian and determinant of Hessian blob detection as well as more general mechanisms for automatic scale selection)

- T. Lindeberg (2008–2009). "Scale-space". in Benjamin Wah. Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Engineering. IV. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 2495–2504. doi:10.1002/9780470050118.ecse609. ISBN 978-0470050118. http://www.nada.kth.se/~tony/abstracts/Lin08-EncCompSci.html. (summary and review of a number of feature detectors formulated; based on a Scale space representation)

- T. Lindeberg; J. Garding (1997). "Shape-adapted smoothing in estimation of 3-D depth cues from affine distortions of local 2-D structure". Image and Vision Computing 15 (6): 415–434. doi:10.1016/S0262-8856(97)01144-X. http://www.nada.kth.se/~tony/abstracts/LG94-ECCV.html. (theory for affine invariant interest points and shape descriptors from second-moment matrices)

- J. Matas; O. Chum; M. Urban; T. Pajdla (2002). "Robust wide baseline stereo from maximally stable extremal regions". pp. 384–393. doi:10.5244/C.16.36. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e045/aafb44693c9de943c750a6b60f2153ac3ccb.pdf.

- K. Mikolajczyk; C. Schmid (2002). "An affine invariant interest point detector". https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00548252/document.

- F. Schaffalitzky; A. Zisserman (2002). "Multi-view matching for unordered image sets, or 'How do I organize my holiday snaps?'". pp. 414–431. http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/publications/2002/Schaffalitzky02/schaffalitzky02.pdf.

- T. Tuytelaars; L. Van Gool (2000). "Wide baseline stereo based on local, affinely invariant regions". pp. 412–422. https://www.cse.unr.edu/~bebis/CS491Y/Papers/Tuytelaars00.pdf.

- S. Agarwal; D. Roth (2002). "Learning a sparse representation for object detection". pp. 113–130. http://host.robots.ox.ac.uk:8080/pascal/VOC/pubs/agarwal02.pdf.

- E. Borenstein; S. Ullman (2002). "Class-specific, top-down segmentation". pp. 109–124.

- R. Fergus; P. Perona; A. Zisserman (2003). "Object class recognition by unsupervised scale-invariant learning". pp. II:264–271. http://host.robots.ox.ac.uk/pascal/VOC/pubs/fergus03.pdf.

- M. Weber; M. Welling; P. Perona (2002). "Unsupervised learning of models for recognition". https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/caf1/83540cd042ab4c0a1b0133a65eaa1ba5784c.pdf.

|