Medicine:Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 17α-hydroxylase deficiency

This article needs editing for compliance with Wikipedia's Manual of Style. In particular, it has problems with does not follow MEDMOS. (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 17 alpha-hydroxylase deficiency |

|---|

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 17α-hydroxylase deficiency is an uncommon form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia resulting from a defect in the gene CYP17A1, which encodes for the enzyme 17α-hydroxylase. It causes decreased synthesis of cortisol and sex steroids, with resulting increase in mineralocorticoid production. Thus, common symptoms include mild hypocortisolism, ambiguous genitalia in genetic males or failure of the ovaries to function at puberty in genetic females, and hypokalemic hypertension (respectively).[1] However, partial (incomplete) deficiency is notable for having inconsistent symptoms between patients,[2] and affected genetic (XX) females may be wholly asymptomatic except for infertility.[3]

Pathophysiology

This form of CAH results from deficiency of the enzyme 17α-hydroxylase (also called CYP17A1). It accounts for less than 5% of the cases of congenital adrenal hyperplasia and is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner with a reported incidence of about 1 in 1,000,000 births. [citation needed]

The most common abnormal alleles of this condition impair both the 17α-hydroxylase activity and the 17,20-lyase activity of CYP17A1. Like other forms of CAH, 17α-hydroxylase deficiency impairs the efficiency of cortisol synthesis, resulting in high levels of ACTH secretion and hyperplasia of the adrenal glands. Clinical effects of this condition include overproduction of mineralocorticoids and deficiency of prenatal and pubertal sex steroids. [citation needed]

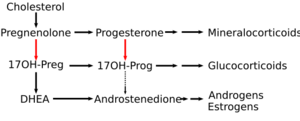

CYP17A1 functions in steroidogenesis, where it converts pregnenolone and progesterone to their 17α-hydroxy forms. The enzyme itself is attached to the smooth endoplasmic reticulum of the steroid-producing cells of the adrenal cortex and gonads. CYP17A1 functions as both a 17α-hydroxylase and a 17,20-lyase. The dual activities mediate three key transformations in cortisol and sex steroid synthesis:[citation needed]

- As 17α-hydroxylase it mediates pregnenolone → 17α-hydroxypregnenolone

- and progesterone → 17α-hydroxyprogesterone.

- As 17,20-lyase it mediates 17α-hydroxypregnenolone → DHEA.

- An expected second 17,20-lyase reaction (17α-hydroxyprogesterone → androstenedione) is mediated so inefficiently in humans as to be of no known significance.

The hydroxylase reactions are part of the synthetic pathway to cortisol as well as sex steroids, but the lyase reaction is only necessary for sex steroid synthesis. Different alleles of the CYP17A1 gene result in enzyme molecules with a range of impaired or reduced function that produces a range of clinical problems.[4]

The dual enzyme activities were for many decades assumed to represent two entirely different genes and enzymes. Thus, medical textbooks and nosologies until quite recently described two different diseases: 17α-hydroxylase deficient CAH, and a distinct and even rarer defect of sex steroid synthesis termed 17,20-lyase deficiency (which is not a form of CAH). In the last decade it has become clearer that the two diseases are different forms of defects of the same gene.[5] However, the clinical features of the two types of impairment are distinct enough that they are described separately in the following sections.[citation needed]

Mineralocorticoid effects

The adrenal cortex is hyperplastic and overstimulated, with no impairment of the mineralocorticoid pathway. Consequently, levels of DOC, corticosterone, and 18-hydroxycorticosterone are elevated. Although these precursors of aldosterone are weaker mineralocorticoids, the extreme elevations usually provide enough volume expansion, blood pressure elevation, and potassium depletion to suppress renin and aldosterone production. Some persons with 17α-hydroxylase deficiency develop hypertension in infancy, and nearly 90% do so by late childhood. The low-renin hypertension is often accompanied by hypokalemia due to urinary potassium wasting and metabolic alkalosis. These features of mineralocorticoid excess are the major clinical clue distinguishing the more complete 17α-hydroxylase deficiency from the 17,20-lyase deficiency, which only affects the sex steroids. Treatment with glucocorticoid suppresses ACTH, returns mineralocorticoid production toward normal, and lowers blood pressure.[6]

Glucocorticoid effects

Although production of cortisol is too inefficient to normalize ACTH, the 50-100-fold elevations of corticosterone have enough weak glucocorticoid activity to prevent glucocorticoid deficiency and adrenal crisis.[6]

Sex steroid effects

Genetic XX females affected by total 17α-hydroxylase deficiency are born with normal female internal and external anatomy. At the expected time of puberty neither the adrenals nor the ovaries can produce sex steroids, so neither breast development nor pubic hair appear. Investigation of delayed puberty yields elevated gonadotropins and normal karyotype, while imaging confirms the presence of ovaries and an infantile uterus. Discovery of hypertension and hypokalemic alkalosis usually suggests the presence of one of the proximal forms of CAH, and the characteristic mineralocorticoid elevations confirm the specific diagnosis.[citation needed]

Milder forms of this deficiency in genetic females allow some degree of sexual development, with variable reproductive system dysregulation that can include incomplete Tanner scale development, retrograde sexual development, irregular menstruation, early menopause, or – in very mild cases – no physical symptoms beyond infertility.[7][8][9] Evidence suggests that only 5% of normal enzyme activity may be enough to allow at least the physical changes of female puberty, if not ovulation and fertility.[citation needed] In women with mild cases, elevated blood pressure and/or infertility is the presenting clinical problem.

17α-hydroxylase deficiency in genetic males (XY) results in moderate to severe reduction of fetal testosterone production by adrenals and testes. Undervirilization is variable and sometimes complete. The appearance of the external genitalia ranges from normal female to ambiguous to mildly underdeveloped male. The most commonly described phenotype is a small phallus, perineal hypospadias, small blind pseudovaginal pouch, and intra-abdominal or inguinal testes. Wolffian duct derivatives are hypoplastic or normal, depending on degree of testosterone deficiency. Some of those with partial virilization develop gynecomastia at puberty even though masculinization is reduced. The presence of hypertension in the majority distinguishes them from other forms of partial androgen deficiency or insensitivity. Fertility is impaired in those with more than minimal testosterone deficiency.[citation needed]

17,20-lyase deficiency

A very small number of people have reportedly had an abnormal allele that resulted primarily in a reduction of 17,20-lyase activity, rather than both the hydroxylase and lyase activities as described above.[10] In these people the defect had the effect of an isolated impairment of sex steroid (e.g., DHEA in the adrenal, but also gonadal testosterone and estrogens) synthesis, whereas mineralocorticoid (e.g., aldosterone) and glucocorticoid (e.g., cortisol) levels remain normal.

Normal aldosterone level can be attributed to the fact that aldosterone is independent of hypothalamus-pituitary axis feedback system, being mainly controlled by the level of serum potassium. Because of the normal aldosterone level, hypertension is not expected.

Normal cortisol level can be explained by the strong negative feedback mechanism of cortisol on hypothalamus-pituitary axis system. That is, in the beginning, 17,20-lyase deficiency will block synthesis of sex steroid hormones, forcing the pathways to produce more cortisol. However, the initial excess of cortisol is rapidly corrected by negative feedback mechanism—high cortisol decreases secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from zona fasciculata of adrenal gland. Thus, there is no mineralocorticoid overproduction. Also, there is no adrenal hyperplasia.

It has also been observed in patients that the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) level remains in the normal range. The reason for this is still unclear.

The sex steroid deficiency produces effects similar to 17α-hydroxylase deficiency. Severely affected genetic females (XX) are born with normal internal and external genitalia and there are no clues to abnormality until adolescence, when the androgenic and estrogenic signs (e.g., breasts and pubic hair) of puberty fail to occur. Gonadotropins are high and the uterus infantile in size. The ovaries may contain enlarged follicular cysts, and ovulation may not occur even after replacement of estrogen.

Management

Hypertension and mineralocorticoid excess is treated with glucocorticoid replacement, as in other forms of CAH. Most genetic females with both forms of the deficiency will need replacement estrogen to induce puberty. Most will also need periodic progestin to regularize menses. Fertility is usually reduced because egg maturation and ovulation is poorly supported by the reduced intra-ovarian steroid production. The most difficult management decisions are posed by the more ambiguous genetic (XY) males. Most who are severely undervirilized, looking more female than male, are raised as females with surgical removal of the nonfunctional testes. If raised as males, a brief course of testosterone can be given in infancy to induce growth of the penis. Surgery may be able to repair the hypospadias. The testes should be salvaged by orchiopexy if possible. Testosterone must be replaced in order for puberty to occur and continued throughout adult life.[citation needed]

See also

- Cytochrome b5 deficiency

- Inborn errors of steroid metabolism

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- Isolated 17,20-lyase deficiency

- Disorders of sexual development

- Intersexuality, pseudohermaphroditism, and ambiguous genitalia

- CYP17A1 (17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase)

References

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) CYTOCHROME P450, FAMILY 17, SUBFAMILY A, POLYPEPTIDE 1; CYP17A1 -609300

- ↑ Yanase, Toshihiko; Imai, Tsuneo; Simpson, Evan R.; Waterman, Michael R. (1992). "Molecular basis of 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase deficiency". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 43 (8): 973–9. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(92)90325-D. PMID 22217842.

- ↑ Levran, David; Ben-Shlomo, Izhar; Pariente, Clara; Dor, Jehoshua; Mashiach, Shlomo; Weissman, Ariel (2003). "Familial Partial 17,20-Desmolase and 17α-Hydroxylase Deficiency Presenting as Infertility". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 20 (1): 21–8. doi:10.1023/A:1021206704958. PMID 12645864.

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) ADRENAL HYPERPLASIA, CONGENITAL, DUE TO 17-ALPHA-HYDROXYLASE DEFICIENCY -202110

- ↑ Miller, Walter L. (2012). "The Syndrome of 17,20 Lyase Deficiency". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 97 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-2161. PMID 22072737.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 C-17 Hydroxylase Deficiency Medication at eMedicine

- ↑ Taniyama, Matsuo; Tanabe, Makito; Saito, Hiroshi; Ban, Yoshio; Nawata, Hajime; Yanase, Toshihiko (2005). "Subtle 17α-Hydroxylase/17,20-Lyase Deficiency with Homozygous Y201N Mutation in an Infertile Woman". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 90 (5): 2508–11. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-2067. PMID 15713706.

- ↑ Miura, K; Yasuda, K; Yanase, T; Yamakita, N; Sasano, H; Nawata, H; Inoue, M; Fukaya, T et al. (1996). "Mutation of cytochrome P-45017 alpha gene (CYP17) in a Japanese patient previously reported as having glucocorticoid-responsive hyperaldosteronism: with a review of Japanese patients with mutations of CYP17". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 81 (10): 3797–801. doi:10.1210/jcem.81.10.8855840. PMID 8855840.

- ↑ Yanase, Toshihiko; Kagimoto, Masaaki; Suzuki, Shin; Hashiba, Kunitake; Simpson, Evan R.; Waterman, Michael R. (1989). "Deletion of a phenylalanine in the N-terminal region of human cytochrome P-450(17 alpha) results in partial combined 17 alpha-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase deficiency". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 264 (30): 18076–82. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)84680-X. PMID 2808364. http://www.jbc.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=2808364.

- ↑ Fernández-Cancio, Mónica; Camats, Núria; Flück, Christa E.; Zalewski, Adam; Dick, Bernhard; Frey, Brigitte M.; Monné, Raquel; Torán, Núria et al. (2018-04-29). "Mechanism of the Dual Activities of Human CYP17A1 and Binding to Anti-Prostate Cancer Drug Abiraterone Revealed by a Novel V366M Mutation Causing 17,20 Lyase Deficiency" (in en). Pharmaceuticals 11 (2): 37. doi:10.3390/ph11020037. PMID 29710837.

Further reading

- Krone, Nils; Dhir, Vivek; Ivison, Hannah E.; Arlt, Wiebke (2007). "Congenital adrenal hyperplasia and P450 oxidoreductase deficiency". Clinical Endocrinology 66 (2): 162–72. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02740.x. PMID 17223983.

External links

|