Medicine:Lactobacillus vaccine

| |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Non-specific bacterial vaginitis, Trichomoniasis |

| Type | Killed/Inactivated |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Gynatren, SolcoTrichovac, Gynevac |

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular injection |

| ATC code | |

Lactobacillus vaccines are used in the therapy and prophylaxis of non-specific bacterial vaginitis and trichomoniasis.[1] The vaccines consist of specific inactivated strains of Lactobacilli, called "aberrant" strains in the relevant literature dating from the 1980s.[1] These strains were isolated from the vaginal secretions of patients with acute colpitis.[2] The lactobacilli in question are polymorphic, often shortened or coccoid in shape and do not produce an acidic, anti-pathogenic vaginal environment.[2] A colonization with aberrant lactobacilli has been associated with an increased susceptibility to vaginal infections and a high rate of relapse following antimicrobial treatment.[2] Intramuscular administration of inactivated aberrant lactobacilli provokes a humoral immune response.[1] The production of specific antibodies both in serum[3] and in the vaginal secretion[4] has been demonstrated. As a result of the immune stimulation, the abnormal lactobacilli are inhibited, the population of normal, rod-shaped lactobacilli can grow and exert its defense functions against pathogenic microorganisms.[1]

Medical uses

Lactobacillus vaccines are primarily used in the therapy and prophylaxis of dysbiotic conditions of the vaginal ecosystem (bacterial vaginitis,[1][5][6] vaginal trichomoniasis,[1][7] and to a lesser extent, vaginal candidiasis[7]). Secondarily, they are used in the prophylaxis and complementary treatment of various urogenital diseases, if vaginal dysbiosis is suspected to be the root cause of the condition. These include (chronic) upper genital tract infections,[8] urinary tract infections[8] and cervical dysplasias.[9] The prophylactic use in patients with a history of late miscarriage and preterm labor is practiced preferably before conception.[10][11][12]

Effectiveness

Bacterial vaginitis

Rüttgers studied the benefit of vaccination with Gynatren in preventing bacterial vaginitis in a patient group with frequent vaginal infections.[4] All of the 192 patients participating in the prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study received local treatment with a tetracycline-amphotericin B vaginal suppository. 95 patients additionally received vaccination with Gynatren, whereas 97 patients were treated with a placebo preparation of identical outward appearance. One month after the start of the treatment 85% of the patients in the active treatment group and 83% in the placebo group were cured (asymptomatic and free from pathogenic bacteria). After 3 months 78% of the verum group and 60% of the placebo group remained free from infection. After 6 months 76% and 40%, and after 12 months 75% and 37% of women in the respective groups were still free from infection.[4]

Another study by Boos and Rüttgers investigated the therapeutic effect of SolcoTrichovac when used as a sole therapeutic agent.[13] The 182 patients enrolled into the study showed symptoms of acute vaginitis, and most of them had been treated for months with topical or oral antibiotics or antimycotics without success. For the course of the study they were advised to refrain from using such preparations. Six months after the first injection 71% of the patients showed a normal vaginal flora according to the classification of Jirovec and Peter.[13] Further studies on the therapeutic and preventive efficacy of lactobacillus vaccines alone or in combination to antimicrobial treatment in bacterial vaginitis have produced similar results.[14][15][16][17][18][19][20]

Vaginal trichomoniasis

Litschgi has investigated the use of SolcoTrichovac both as a therapeutic[21] and as a recurrence prophylactic[22] measure. On the latter subject he reported enrolling 114 women with trichomoniasis into a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 66% of whom had case histories of recurrent vulvovaginitis.[22] All patients as well as their sexual partners received systemic and/or local nitroimidazole treatment. 61 patients were additionally vaccinated with SolcoTrichovac, 53 patients with placebo. At the first follow-up check, 6 weeks after the first injection, 3 patients in each group still had motile trichomonads. Among the patients that were pronounced cured at this visit, a total of 15 reinfections (33.3%) were recorded in the placebo group during the follow-up period from month 4 to month 12 after the first injection, whilst in the verum group there were no new infections.[22] Harris designed a similar randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 198 participants and reported a reinfection rate of 21.6% in the placebo group, in contrast to 3.1% in the SolcoTrichovac group 8 months after completing the course of three injections.[23] Further studies have confirmed the efficacy of lactobacillus vaccines as a powerful complementary treatment and recurrence prophylactic measure in trichomoniasis.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30]

Vaginal candidiasis

Vaginal mycoses are considered a weak indicator that the lactobacillus flora is compromised, since Candida albicans and Lactobacilli can coexist symbiotically.[31] Consequently, immunotherapeutic modulation of the lactobacillus flora has a lesser success rate in this condition than in bacterial and trichomonal vaginitis. Verling reported vaccinating 42 patients with candida-induced chronic colpo-vaginitis with SolcoTrichovac, who had shown resistance to usual fungicidal treatment such as topical amphotericin B, nystatin and povidone-iodine.[18] Of these, 7 patients (17%) have healed and another 18 patients (43%) showed only mild symptoms one month after the third injection.[18]

Urinary tract infections

In many women prone to recurrent urinary tract infections, the mucosal surfaces of the vaginal introitus are colonized by Escherichia coli and Enterococci, rather than Lactobacilli.[32] Reid and Burton have postulated that the vagina may act as a reservoir for uropathogens.[32] In the proposed scenario, the dysbiotic vaginal environment is continually seeding the bladder with infectious microbes leading to a persistent or recurrent urinary tract infection. As they suggested, by recolonizing the vagina with lactobacilli and displacing the pathogens, the infection of the bladder may resolve.[32] No studies have been conducted on the use of lactobacillus vaccines in recurrent urinary tract infections using modern formulations of the vaccine. The inventor of lactobacillus vaccines, Újhelyi reported initial success in preventing uropoietic infections in pregnant women under therapy with experimental single-strain vaccines.[33]

Intrauterine infections during pregnancy

The relationship between intrauterine infections and second-trimester pregnancy loss as well as early preterm delivery has been established.[34][35] Most bacteria found in the uterus in association with preterm labor are of vaginal origin, with only a small minority originating from the abdominal cavity or from an inadvertent needle contamination at the time of amniocentesis.[34] Pathogenic bacteria may ascend through the cervix and maintain a subacute infection of the upper genital tract and the fetal membranes for months before the infection is eventually detected.[34] These infections tend to remain asymptomatic and are not associated with fever, a tender uterus, or peripheral-blood leukocytosis.[34] Often the first symptoms are the rupture of membranes and preterm labor,[34] at which point the conservation of pregnancy becomes difficult.[36] Early treatment and prophylaxis of vaginal infections are crucially important especially in those patients, that have already experienced a second-trimester miscarriage, which is associated with 27% rate of recurrence (pregnancy loss between 14 and 23 6⁄7 weeks of gestation), 10% rate of extremely preterm delivery (24 to 27 6⁄7 weeks), and further 23% rate of very, moderate or late preterm delivery (28 to 36 6⁄7 weeks) in the subsequent pregnancy.[37]

A study performed by Lázár and her coworkers examined the incidence of low-birth-weight offspring among therapeutically and preventively vaccinated women.[10] Out of 413 pregnant women presenting with acute urogenital infections, 209 were vaccinated with Gynevac additionally to conventional antimicrobial treatment, whereas 204 women only received antimicrobial therapy. A birth-weight below 2500 g was recorded in 10.4% of vaccinated patients compared to 24.1% among patients that had not received lactobacillus vaccination. The rate of perinatal mortality was 1.42% in the vaccinated group in contrast to 3.86% among non-vaccinated patients. On average the gestational period was longer in vaccinated patients, 81.3% of whom reached full term, in contrast to only 66.7% of the non-vaccinated patients. Preventive lactobacillus vaccination with Gynevac was performed on 1396 healthy women, partly before conception and partly during early pregnancy. The reported incidence of low birth weight was 7.9% among vaccinated women compared to 14.0% among healthy controls.[10] In a subsequent prospective study with the participation of 1852 vaccinated pregnant women and 1418 controls, Lázár and coworkers reported a preterm birth rate of 7.1% among vaccinated women and 12.2% among those that declined lactobacillus vaccination.[12]

Formulation

Each ampoule of Gynatren contains at least 7×109 inactivated microorganisms of eight Lactobacillus strains in approximately equal amounts (8.75×108 microorganisms per strain). Three strains belong to the species L. vaginalis, three strains to L. rhamnosus, one strain to L. fermentum and one to L. salivarius.[38] The eight specific aberrant polymorphous Lactobacillus strains have been deposited at the Westerdijk Institute (Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures) in 1977 under the strain numbers CBS 465.77 to CBS 472.77.[39] Inactivated material from the eight strains is mixed and diluted with physiological sodium chloride solution. Phenol is added as a preservative. The vaccine usually has a total nitrogen content of 3.68 mg in 100 ml solution (based on the dry material, using the Kjeldahl method).[39] Using the conversion factor of 6.25 to convert nitrogen concentration to protein concentration, this means that there is on average 0.115 mg bacterial proteins in each ampoule of 0.5 ml.

Gynevac is composed of five specific aberrant polymorphous Lactobacillus strains, four belonging to the species L. fermentum and one to the species L. reuteri. The further ingredients are formaldehyde and sodium ethylmercuric thiosalicylate (Thiomersal) as preservatives and sodium chloride solution as a diluent. Each ampoule of 1 ml contains between 0.08 mg and 0.32 mg bacterial proteins.[40]

Schedule

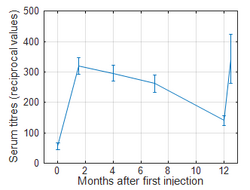

The usual vaccination schedule of Gynatren is 3 intramuscular injections of 0.5 ml vaccine at intervals of 2 weeks, followed by a booster dose of 0.5 ml 6–12 months after the first injection.[38] The booster injection raises the serum antibody titres in most cases back to similar levels to those found shortly after primary vaccination and ensures renewed immune protection for about 2 further years.[38][41] Grčić et al. recommends the periodic administration of booster doses every 2 years to maintain protective immunity for many years.[41]

The schedule of Gynevac includes 5 intragluteal injections of 1 ml vaccine at intervals of 10 days.[40] Protective immunity is conferred for about a year. The primary immunization program may be repeated, if reinfection or relapse occurs.[42]

Side effects

Common side effects include pain, redness and swelling or hardening of the tissues at the injection site. Systemic vaccination reactions commonly include fatigue, flu-like symptoms, a raised temperature between 37 and 38 °C (98.6 and 100.4 °F), shivering, headache, dizziness, nausea and a swelling of the inguinal lymph nodes. Symptoms usually subside within days after injection and are less pronounced or absent at subsequent injections.[38]

Contraindications

Gynatren is contraindicated in patients with a history of allergic reaction to the bacterial antigens or phenol contained in the vaccine. Further contraindications are acute fever, active tuberculosis, severe hematopoietic disorders, decompensated cardiac or renal insufficiency, autoimmune and immunoproliferative diseases.[38] Gynevac is additionally contraindicated in arthritides affecting several joints, under immunosuppressive- or radiotherapy.[40]

Pregnancy

Lactobacillus vaccines are not contraindicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[1] Both Gynatren and Gynevac may be prescribed during pregnancy upon careful individual consideration of the potential risks and benefits.[38][40] Lázár reported vaccinating 3457 pregnant patients with Gynevac between 1976 and 1982, usually starting the vaccination schedule at the first prenatal care visit, and has not observed any impairment of pregnancy or teratogenic effect in association to the lactobacillus vaccine.[10][12] Rüttgers made similar observations about Gynatren when administered in the second trimester.[4]

Mechanism of action

The mechanism of action of lactobacillus vaccines is far from being completely understood. At least three theories have been proposed. The most commonly accepted one, as formulated by Påhlson and Larsson, suggests that the vaccine breaks the immune tolerance of the host and makes it possible for the immune defense to attack aberrant, "ecologically wrong" lactobacilli and create an environment for beneficial strains to become dominant.[43] Rüttgers on the other hand described SolcoTrichovac as an anti-adhesive vaccine, suggesting that the induced antibodies and perhaps other mechanisms inhibit the adhesion of microbes to epithelial cells in a largely nonspecific manner.[44] A third hypothesis, advanced by Goisis among others, involves the possibility of an immunomodulation resulting in tolerance, rather than defense against the bacterial antigens used in the vaccine.[28]

Multiple authors have proposed cellular immunological phenomena as the primary mediators of protective effect of lactobacillus vaccines.[2][44][45] Studies into cellular immunity are technically challenging in humans owing to the difficulty of sampling lymphoid tissues as opposed to secretions, and none has been performed so far on lactobacillus vaccines. A number of studies have been published on the humoral responses to primary and booster immunization in serum[3][14][41][23] and in the vaginal secretions.[46][13][4] Rüttgers identified mucosal secretory IgA as a strong immune correlate of vaccine efficacy.[4]

Humoral immune response

Mucosal surfaces are a major portal of entry for pathogens into the body. Antibodies in mucosal secretions represent the first line of immune defense of the mucosae. They are capable to bind to specific pathogens and prevent their adherence to the epithelial cell lining of the mucous membranes. Neutralized pathogens can then be eliminated from the mucosal surfaces by means of conveyance by the mucus stream. Mucosae throughout the body have been described as parts of a common mucosal immune system (CMIS). The basis for this concept is the observation that precursor lymphocytes sensitized to a certain antigen at a specific mucosal site can migrate and assume effector function at distant mucosal tissues.[47] Although the female genital tract is thought of as part of the CMIS, it shows some characteristics that set it apart from other mucosal immune sites. One of these features is the relative inefficacy of local antigenic stimulation owing to a sparsity of mucosal lymphoepithelial inductive sites.[48] A further distinctive characteristic is the significant contribution of the systemic immune compartment to the pool of antibodies. In most external secretions, like tears, saliva or milk, the dominant antibody class is secretory IgA (sIgA), whereas in the cervicovaginal secretions IgG levels equal or exceed the levels of sIgA.[49][48] A large portion of this IgG is thought to originate from the circulation and appear in vaginal fluids via transudation through the uterine tissues.[49][48] There are reports that systemic immunization can stimulate humoral immune protection in vaginal secretions more efficiently than in other mucosal secretions, where serum-derived IgG concentrations remain lower.[50][49]

Milovanović and coworkers studied the serum antibody response of 97 women with trichomonad colpitis to primary immunization with SolcoTrichovac (3 intramuscular injections of 0.5 ml vaccine at intervals of 2 weeks) and a booster dose of 0.5 ml administered 12 months after the first injection.[3] The agglutination titres were determined by preparing two-fold serial dilutions of the serum samples in isotonic saline (dilutions of 1:10 to 1:1280), using 0.5 ml concentrated lactobacillus vaccine as an agglutinogen. An at least threefold elevation of the agglutination titres following primary immunization was detected in the serum of 93.8% of patients; the rest of the patients were considered non-responders or poor responders to the vaccination. The geometric mean of the agglutination titres increased from the basal level of 1:56 before vaccination to 1:320 after finishing the primary immunization program, and it was still 1:140 one year later. Two weeks after the booster injection the mean titres were raised back to 1:343.[3]

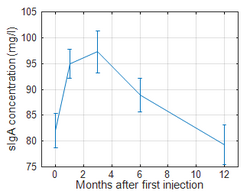

Rüttgers quantified the total concentration of secretory IgA antibodies in the vaginal secretions of 192 women with bacterial vaginitis participating in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.[4] 95 patients were treated with SolcoTrichovac and 97 with placebo, according to the primary immunization scheme described above. The samples were tested using the enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay according to Åkerlund et al.[51] The mean baseline concentrations were similar in the two comparative groups. One month after the start of the therapy the sIgA concentration in the active-treatment group had risen significantly compared to the baseline and also in comparison to the placebo group. This difference gradually decreased over the subsequent months. After 12 months the sIgA concentration in the SolcoTrichovac group had fallen back to baseline value. About 35% of the actively treated patients had not developed a pronounced mucosal immune response. In these patients sIgA concentration of the vaginal secretion remained unchanged or showed only a short-lived elevation. Rüttgers observed that this group of patients by large overlapped with those, that had had reinfections during the follow-up period of 12 months, and concluded that vaginal sIgA concentration is a better correlate to immune protection than serum antibody titres.[4]

On the question of the mechanism underlying the induction of IgA-secreting plasma cells in the vaginal mucosa, Pavić and Stojković suggested that intramuscularly administered antigens may be transported to the local immunocompetent organ, in this case the vagina, and provoke a local secretory immune response.[2] Patrolling dendritic cells exposed to killed bacterial antigens at a muscular injection site however typically do not migrate further than the local draining lymph nodes, where antigen presentation and the activation of T and B cells occur.[52] Effector and memory lymphocytes in turn preferentially home back to the tissue where they were first activated, in this case the secondary lymph nodes.[53] This is the reason why parenteral immunization with non-replicating antigens is generally considered ineffective in eliciting a mucosal immune response.[52] Another possible explanation for an increased level of anti-aberrant-lactobacillus sIgA in vaginal secretions involves natural priming by mucosal infection at this site. Similarly to how subcutaneously administered killed whole-cell cholera vaccines reportedly only provoke substantial mucosal secretory antibody response in cholera‐endemic countries,[54] vaginal priming with aberrant lactobacilli may be necessary for the generation of mucosal IgA-secreting plasma cells following parenteral vaccination.

Effect on the vaginal ecology

Protective lactobacilli inhibit the growth of other microorganisms by competing for adherence to epithelial cells and by producing antimicrobial compounds.[55] These compounds include lactic acid, which lowers the vaginal pH, hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins.[55] Aberrant strains of Lactobacilli are incapable to effectively control the vaginal microbiota, leading to an overgrowth of a mixed flora of aerobic, anaerobic and microaerophilic bacterial species.[2] Antibodies and cellular defense mechanisms directed against aberrant lactobacilli induced by vaccination have been shown to change the composition of the vaginal flora.[2] Milovanović and his coworkers found a marked reduction in prevalence of Klebsiella and Proteus infestations in 36 trichomoniasis patients under therapy with SolcoTrichovac, while normal, metabolically active Lactobacillus species that could initially be found in only 11% of patients, were present in 72% after finishing treatment.[56] Karkut observed a significant reduction in the incidence of Escherichia coli (55% to 23%), Group B Streptococci (37% to 10%), Enterococci (36% to 12%), Bacteroides (25% to 3%) and Gardnerella vaginalis (37% to 9%) in 94 patients treated for recurrent bacterial vaginitis eight weeks after initial injection.[15] The incidence of aberrant lactobacilli fell from 17% to 3%, while that of normal lactobacilli rose from 31% to 72% during the course of the eight weeks.[15] Harris reported a significant reduction of the number of microbial species (other than lactobacilli) found in post-treatment cultures from 77 patients.[16] Litschgi found, that the incidence of mixed bacterial infections characterized by the presence of G. vaginalis, haemolytic Streptococci and Staphylococci was reduced by two-thirds four weeks after finishing therapy in 120 patients treated for bacterial colpitis.[17] He observed a similar reduction of the less frequent Klebsiella, Proteus-dominant infections.[17]

A quantitative bacteriological analysis has been performed by Milovanović and coworkers in a group of 36 trichomoniasis patients.[56] The study aimed at quantifying locally unusual and mostly pathogenic organisms, whereby anaerobes were excluded for methodological reasons. Bacterial counts of aerobes excluding lactobacilli reportedly dropped from 18,900 organisms per 0.1 ml vaginal secretion on the day of the first SolcoTrichovac injection to 5800 organisms 112 days thereafter.[56] Goisis and his coworkers reported a mean count of lactobacilli of 1.6×106 organisms per ml vaginal secretion before vaccination with SolcoTrichovac in 19 trichomoniasis patients.[14] One month after the start of the treatment the count increased to 4.6×106 bacilli per ml. In 46 patients with bacterial vaginitis the lactobacillus counts were significantly higher during the entire course of treatment with 8.6×106 bacilli per ml before and 15×106 bacilli per ml after vaccination. While this study summed the counts of normal and aberrant lactobacilli, microscopic study of the fixed, Gram-stained smears of vaginal secretions revealed lactobacilli of differing lengths, with a predominance of short forms in trichomoniasis patients before vaccination; the bacilli retained this tendency even in cultures started from the secretion samples. The morphology of lactobacilli shifted towards normal rod-shaped forms under therapy in most patients, which property was once again retained in culture.[14] Müller and Salzer have confirmed the quantitative increase in physiological lactobacilli under vaccination therapy of 28 patients with recurrent bacterial infections.[57]

The decreasingly diverse and numerous populations of non-lactic acid-producing bacteria and the concurrent growth of normal, metabolically active lactobacilli lead to a gradual decrease of vaginal pH. Goisis and his coworkers reported in trichomoniasis patients a mean pH value of 6.14 at the time of the first injection, 5.64 two weeks later, and 5.23 on the day of treatment completion, two weeks after the second visit.[14] In patients with vaginitis not caused by trichomonads a mean initial pH of 5.81 was documented, which dropped to 5.39 two weeks later and finally to 4.98.[14] Karkut has published very similar results.[15] Boos and Rüttgers measured in 182 patients with bacterial vaginitis a vaginal pH of 4.90 before therapy and 4.26 six months after the start of therapy.[13]

History

Invention

In 1969 a research project was started in Budapest, Hungary to develop a vaccine against trichomoniasis, initiated by György Philipp, a Hungarian gynaecologist and led by Károly Újhelyi, head of the Vaccine Production and Research Department of the Hungarian Institute of Public Health, one of the most distinguished Hungarian physician-scientists of the 20th century and a pioneer of vaccine research and technology.[42] In 1972 the research group reported vaccinating 300 patients with acute trichomonal colpitis with autovaccines consisting primarily of inactivated Trichomonas vaginalis strains cultured from vaginal samples of the patients themselves, along with some residual amounts of the accompanying bacterial flora, inadvertently present in the cultures.[33] Despite of a marked alleviation of clinical symptoms, all trichomoniasis patients still tested positive upon completion of the autovaccine therapy.

Újhelyi and his coworkers attributed the partial therapeutic effect to the bacterial residue in the T. vaginalis cultures used for the vaccine.[33] They identified a Gram-positive Lactobacillus with a tendency to polymorphism commonly present in the accompanying flora of trichomoniasis patients. To test their assumption, further 700 patients each received treatment with an inactivated bacterial vaccine composed of one of 16 such polymorphic Lactobacillus strains. The effect was studied on eight patient groups with the following conditions: (1) colpitis, including trichomonal colpitis (2) erythroplakia (3) endocervicitis (4) upper genital tract infection (5) urinary tract infection (6) infertility (7) genital lesions and tumors (8) trichomoniasis during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum period. Treatment with the experimental bacterial vaccines was capable to eliminate trichomoniasis in 28% of infected patients and resolved or alleviated many of the examined urogenital conditions.[33] After this initial breakthrough, Újhelyi and his coworkers directed their efforts into the development and optimization of Gynevac, a composite bacterial vaccine, containing five aberrant, polymorphic Lactobacillus strains.[58] Erika Lázár, a Hungarian gynaecologist and specialist in the field of reproductive medicine, and her coworkers performed many of the clinical trials on Gynevac, focusing clinical and research interest on the prevention of ascending infections during pregnancy.[11] In two prospective studies performed between 1976 and 1982 in rural, socioeconomically disadvantaged Kazincbarcika with the enrollment of nearly 3500 pregnant women, lactobacillus vaccination appeared to reduce the incidence of preterm birth by about 40%.[10][12]

1980-2012

In 1975 the research group of Újhelyi sold the unpatented technology to Solco Basel AG, a Swiss pharmaceutical company with the agreement, that Solco would manufacture and market the vaccine in Western Europe, whereas the Hungarian company HUMÁN Oltóanyagtermelő Vállalat (later Vakcina Kft.) would supply the Eastern markets ("Soviet Bloc").[42] In 1980 Solco's researchers patented the vaccine;[39] in 1981 the company obtained regulatory approval and started marketing the vaccine under the trade name SolcoTrichovac.[42] After prolonged clinical trials, mainly driven by Lázár, the production and marketing of Gynevac started in Hungary in 1997.[42]

After Solco's acquisition of the technology, mainly Swiss and German researchers have joined the investigations. In 1980 Mario Litschgi reported a cure rate of trichomoniasis of 92.5% in a clinical study with 427 female participants.[21] Following this initial success, a number of studies have been conducted on the vaccine. Most of the reports can be found in the proceedings of two symposia: the Symposium on Trichomoniasis (1981)[59] featured investigations with Trichomonas vaginalis-infected women and mainly clinical results, whereas the Symposia on the Immunotherapy of Vaginal Infections (1983)[60] focused on the therapy of bacterial infections and delved into the mechanism of action. Solco continued to develop the formulation, during the course of which the new species Lactobacillus vaginalis was identified in 1989.[61] In the same year, the Hamburg-based pharmaceutical company Strathmann GmbH & Co. KG. overtook production of the vaccines SolcoUrovac (now named Strovac) and SolcoTrichovac (now named Gynatren).[62]

2012-today

In 2012 Gynevac was withdrawn from the market, not due to any unexpected adverse effects, but rather due to Vakcina Kft. failing to obtain regulatory compliance upon the EU-accession of Hungary.[42] Today Gynatren is the only lactobacillus vaccine marketed for the treatment of non-specific bacterial vaginitis and trichomoniasis, and it is mostly only prescribed by a select few gynaecologists in the DACH countries and Hungary. In Germany the vaccine may be covered by health insurance upon individual deliberation of the attending gynaecologist.[63]

Research

Research interest in lactobacillus vaccines peaked in the 1980s. The technical and theoretical advances in the fields of microbiology, immunology and vaccinology of the past few decades could help shed new light on the still not fully clarified mode of action of these clinically promising vaccines. More research is warranted to elucidate the distinct properties of "aberrant" strains of Lactobacilli, the exact mechanism by which they contribute to or accompany pathologies, the determinants of colonization in different groups of individuals. A further point of interest is the specificity of the immune stimulation – whether vaccination induces cross-reacting antibodies with any other microorganism. A comparative study on lactobacillus heterovaccines like Gynatren and gynaecological autovaccines such as GynVaccine[64][65] has yet to be performed.

Lactobacillus strains used in the vaccines

Characteristics

It has not been clarified by what mechanism the lactobacilli used in the vaccines ("aberrant" lactobacilli) fail to confer protection against vaginal pathogens. At the time of invention, available knowledge of the various health-promoting mechanisms of lactobacilli was very limited. For example, Eschenbach's seminal work on H2O2-producing lactobacilli has not been published until 1989;[66] at this point scientific efforts to clarify the vaccine's mechanism of action have already subsided.

The nutrient medium, carbohydrate fermentation profile, and microscopic appearance of the strains used in SolcoTrichovac have been described.[39][28] Growth on an iron-enriched medium of 0.12 mᴍ concentration of FeSO4·7H2O is rather unusual for a lactobacillus species,[67][68] and resembles the nutrient needs of L. iners,[69] a vaginal lactobacillus associated with bacterial vaginosis[70][71][72] and preterm birth,[73][74] known for its ambiguous morphology, including coccobacillar cells[75][69] (not used in the vaccine[38]).

Påhlson and Larsson hypothesized, that the defining characteristic of the lactobacilli used in SolcoTrichovac is a missing H2O2-production, which has not been confirmed.[43] Moreover, the correlation they found between bacterial cell morphology and health benefits, pointed towards an association between long uniform lactobacilli and decreased protection against vaginal infections, whereas polymorphic/shortened lactobacilli were described as innocuous inhabitants of the vaginal econiche.[43][76] It seems, that the authors equated the strains used in SolcoTrichovac to those responsible for cytolytic vaginosis,[43] which is generally considered a different condition, characterized by a lactobacillus overgrowth,[77] rather than the depletion seen in patients colonized by the strains used in the vaccine.[56][14]

Various other properties that could potentially play a role in the (lack of) protective effect, like the ratio of L-lactic acid to D-lactic acid production (correlated to MMP-8 concentrations of the vaginal fluid),[78] adhesion competition, self- and co-aggregation ability, production of bacteriocins, organic acids or biosurfactants,[79][80] immunomodulatory properties,[81][82] or toxin production such as seen in L. iners[83][84] remain obscure for the time.

Risk factors of colonization

The inventor of lactobacillus vaccines, Újhelyi described the strains used in Gynevac as pathobionts to Trichomonas vaginalis.[33] He considered colonization with "aberrant", unprotective strains of lactobacilli, and their persistence even after protozoan infection has been cleared, a chronic post-infectious complication, and introduced the term "lactobacillus syndrome" for the condition[33] (not to be confused with the distinct pathologies of cytolytic vaginosis[77] and vaginal lactobacillosis[85][86][87]). Scattered reports suggest that some minority of Lactobacillus strains found in humans indeed enhance rather than inhibit parasite adhesion to the vaginal epithelium. In vitro preincubation of vaginal epithelial cells (VECs) with physiological concentrations (1×107–1×108 CFU/ml) of Lactobacillus CBI3 (a human isolate of L. plantarum or L. pentosus) increased the number of T. vaginalis cells able to adhere to the VEC monolayer up to eightfold.[88] McGrory and Garber reported a significant prolongation of T. vaginalis infection in estrogenized BALB/c mice intravaginally preinoculated with 1×109 cells of L. acidophilus ATCC 4356 (originating from the human pharynx) in comparison to animals that had not been pretreated.[89] Although initial infectivity in the two groups was comparable, at day 24 post-infection 69% of L. acidophilus-inoculated mice still showed positive T. vaginalis cultures, compared with only 11% of mice not harboring lactobacilli.[89]

Other hypothesized risk factors of colonization by lactobacilli of low protective value in general include prior antimicrobial treatment[43][90][91][92] and congenital factors.[43]

Association with T. vaginalis

Soszka and Kuczyńska described the appearance of morphological variations of Lactobacilli, when grown in the presence of a high concentration of Trichomonas vaginalis.[93] The authors interpreted the observed atypical (coccoid) cell morphology as an involution (senescent, dying) form.[93][94] Goisis et al. have shown, that shortened and coccoidal lactobacilli are not only present in the primary secretion samples of trichomoniasis patients, but also in the cultures started from these samples, free from competitive microorganisms and under optimal culture conditions, suggesting that the coccoid bacteria may represent a distinct viable phenotype.[14] Contrastingly, the isolates from vaccinated patients tended to assume bacilliform also in culture.[14] The general consensus remains, that at least some of the morphology variants seen under trichomoniasis versus health are to be interpreted as representations of "true commensal" versus more pathogenic strains (genotypes),[59][60] although a possible relationship between morphotype and distinct environment-driven proteome profiles has not been excluded.[14]

Immunological cross-reaction with T. vaginalis

The antigenic material responsible for the effect of lactobacillus vaccines is most likely surface antigens of the aberrant lactobacilli.[95] The anti-trichomonal effect of SolcoTrichovac has led multiple researchers to investigate the possibility of shared surface antigens between the specific strains used in the vaccine and T. vaginalis. The theory of antigenic cross-reactivity was put to the test by Stojković.[45] Indirect immunofluorescence was performed on trichomonads treated with rabbit antisera against aberrant lactobacilli and against T. vaginalis. Specific immunofluorescence was observed on those protozoa which had been treated with anti-lactobacillus serum and anti-trichomonas serum, but not on those treated with serum from non-vaccinated animals.[45] Bonilla-Musoles performed an electron microscopic study on trichomonads treated with serum from women who were previously vaccinated with SolcoTrichovac.[96] After three days the trichomonads exposed to antibody-containing serum showed marked signs of destruction, similar to those observed under the influence of metronidazole. The electron micrographs revealed cytoplasmic swelling, dilation of the reticuloendothelial lamellae and formation of vacuoles as well as evaginations and invaginations of cellular membranes.[96] Alderete, Gombošová and others however described contrary findings, and attributed any anti-trichomonal activity of lactobacillus vaccines to non-specific immune mechanisms.[97][98] The question of immunological relationship between aberrant lactobacilli and T. vaginalis has not been answered conclusively.

Phylogenetic relationships to T. vaginalis

An intriguing hypothesis was advanced by Alain de Weck that suggests horizontal gene transfer between specific aberrant strains of Lactobacilli used in SolcoTrichovac and T. vaginalis, which leads to their (possible) cross-immunogenicity.[95] Phylogenetic relationships between T. vaginalis and aberrant lactobacilli have not been studied. Nevertheless, multiple examples of gene transfer between the parasite and bacteria have been documented.[99][100] Audrey de Koning argues that lateral transfer of the N-acetylneuraminate lyase gene from Pasteurellaceae to T. vaginalis may have been a key factor in the adaptation of Trichomonas to parasitism.[101] In an analogous manner, Buret et al. suggest gene exchanges between enteropathogens and normal microbiota during acute enteric infection as one of the possible causative factors behind post-infectious intestinal inflammatory disorders.[102]

Alternative theory of the mechanism of action

Goisis and his colleagues proposed an alternative hypothesis on the mechanism of action of SolcoTrichovac, suggesting that anti-lactobacillus antibodies may stimulate proliferation of lactobacilli rather than their (strain-specific) damage or inhibition.[28] Among the circumstances they cited to support this theory, is their opinion that antibodies specific to one strain of Lactobacillus would most likely cross-react with several antigens present on various other strains (yet, both the concentration of anti-lactobacillus sIgA antibodies[46][13][4] and lactobacillus counts[14][57] have been demonstrated to increase in vaccinated women).[28] Further they referred to the inconspicuous metabolic profile and the lack of a verified pathomechanism of the strains used in SolcoTrichovac, suggesting that they may represent mere morphotypes rather than pathogenic/unprotective biotypes.[28] The proposed theory relies on analogies with other known examples of non-classical, stimulatory/homeostatic antibody-antigen interactions.[28] Notably, the majority of intestinal bacterial cells in healthy individuals is bound by sIgA.[103][104] The sIgA-coating of commensal enteric bacteria is believed to promote intestinal microbial homeostasis by a number of mechanisms. Secreted IgA anchors commensal bacteria to the mucus[103] and facilitates biofilm formation,[105] thereby limiting their translocation from the lumen into mucosal tissues.[106][107] This minimizes activation of the innate immune system, a process termed "immune exclusion".[103] Furthermore, the selective uptake of sIgA-microbe immune complexes by dendritic cells (DCs) in lymphoid follicles has been shown to induce semimaturation of the DCs.[108][107] The resulting, so-called tolerogenic DCs downregulate the expression of T cell costimulatory molecules and proinflammatory cytokines.[109][107] The altered immune signaling favours local processing of antigens and a rapid induction of low-affinity, broad-specificity IgA, leaving the systemic immune compartment ignorant about these organisms.[110] In contrast, direct translocation of non-sIgA-coated microbes or microbial products across the epithelium preferentially results in proinflammatory signalling and a systemic response against the invading agent, involving affinity-matured serum antibodies of the classes IgA, IgE and IgG.[110][107] Lastly, binding by sIgA can downregulate the expression of virulence factors e.g. involved in adhesion or nutrient acquisition by commensal bacteria.[111] If the homeostasis breaks down, innate immune responses directed against commensal enteric bacteria lead to a shift in the species composition (dysbiosis).[112] Invasive species are better equipped to resist or take advantage of host inflammatory mechanisms and in the perturbed niche successfully compete with the resident microbiota.[103] Hypersensitivity responses to commensal enteric microbiota and a perturbation of microbial ecology is observed in many patients with chronic enterocolitis.[112]

This alternative theory coincides with the observation that women without a history of urinary tract or vaginal infections harbor higher antibody levels against vaginal lactobacilli than women with a history of these infections.[113] Alvarez-Olmos and her coworkers reported an approximately fourfold elevation of total IgG and a threefold elevation of total IgA concentration in the cervicovaginal secretions of adolescent women colonized with H2O2-producing lactobacilli (associated with vaginal health) in comparison to those colonized with non-H2O2-producing lactobacilli.[114][104]

Goisis et al. described lactobacillus vaccination as a means to systemically boost a diminished pool of lactobacillus-specific vaginal antibodies, likely increasing the potential for immune exclusion and tolerogenic responses to the microorganisms.[28] They added to this a further hypothetical notion: loss of lactobacillus-specific sIgA may be characteristic to patients co-colonized by bacteria capable to gradually desialylate and finally proteolytically degrade sIgA,[28] a known impairment of the vaginal defense system,[115][116] established in the context of Gardnerella vaginalis-specific antibodies.[115] This contrasts with other proposed mechanism of sIgA deficiency, such as the loss of immunomodulatory strains or host immunodeficiency.[4]

Although Goisis et al. announced ongoing experiments and preliminary results to prove this theory, as well as the possible cross-reactivity of "normal", ecologically beneficial lactobacilli with antibodies directed against the strains used in SolcoTrichovac,[28] a conclusive report has not been publicized to date.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 (in German) Vaginose, Vaginitis und Zervizitis. Mit Bildteil zu Vulvovaginalerkrankungen. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. 1995. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-10739-3. ISBN 978-3-540-58553-4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Vaccination with SolcoTrichovac. Immunological aspects of a new approach for therapy and prophylaxis of trichomoniasis in women". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (Suppl 2): 27–38. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269590. PMID 6629132.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Serological study with SolcoTrichovac, a vaccine against Trichomonas vaginalis infection in women". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (Suppl 2): 39–45. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269592. PMID 6629134.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 "Bacterial vaginitis: protection against infection and secretory immunoglobulin levels in the vagina after immunization therapy with Gynatren". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 26 (3): 240–9. 1988. doi:10.1159/000293700. PMID 3240892.

- ↑ "Impfung mit Gynatren – ergänzende Therapiemaßnahme bei Kolpitis" (in German). Gynäkologische Praxis 29 (2): 224. 2005. ISSN 0341-8677.

- ↑ "Infektionen, Impfungen, Reisemedizin" (in German). Praxisleitfaden Allgemeinmedizin (7th ed.). Urban & Fischer. February 2014. pp. 449–571. doi:10.1016/C2012-0-02874-8. ISBN 978-3-437-22445-4.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Impfstoff Gynatren: Erfolgreiche Therapie rezidivierender Kolpitis" (in German). Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 98 (47): A-3146. 2001.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Role of Lactobacillus in Urogenital Inflammations and their Treatment with Vaccination". Symposium cum Participatione Internationali de Biocenosis Vaginae. Smolenice. 14–15 October 1983.

- ↑ "Effect of immunopotentialization on rate of vaginal smear normalization according to appearance of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 28 (1): 41–4. January 1989. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(89)90542-0. PMID 2565829.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 "Kis súlyú újszülöttek arányszámának csökkentése terhesek lactobact vakcinációjával" (in Hungarian). Orvosi Hetilap [Physician's Weekly] 122 (37): 2263–8. September 1981. PMID 7312342.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 András Klinger, ed (5–6 October 1982). "Meddőség kezelése a felszálló nőgyógyászati gyulladások gyógyításának új módszerével" (in Hungarian). A termékenység, családtervezés, születésszabályozás jelene és jövője: Tudományos kongresszus [Scientific Congress on the Present and Future of Fertility, Family Planning and Birth Control]. Budapest: Magyar Család- és Nővédelmi Tudományos Társaság [Pro Familia Hungarian Scientific Society]. pp. 75–77.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 "A koraszülést befolyásoló tényezők vizsgálata Kazincbarcikán, különös tekintettel a Lactobacillus vakcinációra" (in Hungarian). Magyar Nőorvosok Lapja [Journal of Hungarian Gynaecologists] (51): 353–356. 1988.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 "A new therapeutic approach in non-specific vaginitis". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 7–16. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269919. PMID 6537385.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 "Effects of vaccination with SolcoTrichovac on the vaginal flora and the morphology of the Doederlein bacilli". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (Suppl 2): 56–63. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269598. PMID 6629136.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "Effect of lactobacillus immunotherapy (Gynatren/SolcoTrichovac) on vaginal microflora when used for the prophylaxis and treatment of vaginitis". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 17–24. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269921. PMID 6537382.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Gynatren/SolcoTrichovac in the treatment of non-specific vaginitides". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 50–7. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269926. PMID 6336151.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Treatment of non-specific colpitis with Gynatren/SolcoTrichovac". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 58–62. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269927. PMID 6336152.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Treatment of chronic colpo-vaginitis by stimulation of the immune system". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 81–90. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269930. PMID 6537387.

- ↑ "Impfung gegen nichtspezifische bakterielle Vaginose. Doppelblinduntersuchung von Gynatren" (in German). Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 31 (3): 153–60. 1991. doi:10.1159/000271648. PMID 1761240.

- ↑ "An audit of Gynatren (a Lactobacillus acidophilus lyophilisate) vaccination in women with recurrent bacterial vaginosis". International Journal of STD & AIDS 5 (4): 299. July 1994. doi:10.1177/095646249400500416. PMID 7948165.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Wirkung einer Laktobazillus-Vakzine auf die Trichomonas-Infektion der Frau. Vorläufige Ergebnisse" (in German). Fortschritte der Medizin 98 (41): 1624–7. November 1980. PMID 6781998.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "SolcoTrichovac in the prophylaxis of trichomonad reinfection. A randomized double-blind study". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (Suppl 2): 72–6. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269602. PMID 6354888.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Double-blind comparative study of Trichomonas vaginalis infection: SolcoTrichovac versus placebo". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 44–9. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269925. PMID 6399488.

- ↑ "Clinical experience using SolcoTrichovac in the treatment of trichomonas infections in women". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (Suppl 2): 64–71. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269600. PMID 6629137.

- ↑ "SolcoTrichovac in medical practice. An open, multicentre study to investigate the antitrichomonal vaccine SolcoTrichovac". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (Suppl 2): 77–84. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269603. PMID 6629138.

- ↑ "The therapeutic and prophylactic efficacy of SolcoTrichovac in women with trichomoniasis. Investigations in Cairo". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (Suppl 2): 85–8. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269604. PMID 6629139.

- ↑ "Immunotherapy in vaginal trichomoniasis--therapeutic and prophylactic effects of the vaccine SolcoTrichovac". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 63–9. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269928. PMID 6399489.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 28.7 28.8 28.9 "Modification of the vaginal ecology by Gynatren/SolcoTrichovac". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 70–80. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269929. PMID 6537386.

- ↑ "Clinical experience with SolcoTrichovac in the treatment of vaginal trichomoniasis". East African Medical Journal 61 (5): 372–375. May 1984. PMID 6439544.

- ↑ "Vacunación con SolcoTrichovac en trichomoniasis vaginal" (in Spanish). Revista Chilena de Obstetricia y Ginecologia 52 (3): 193–7. May 1987. PMID 3274669.

- ↑ "Hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli and acquisition of vaginal infections". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 174 (5): 1058–63. November 1996. doi:10.1093/infdis/174.5.1058. PMID 8896509.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Use of Lactobacillus to prevent infection by pathogenic bacteria". Microbes and Infection 4 (3): 319–24. March 2002. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(02)01544-7. PMID 11909742.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 "A trichomonas syndroma" (in Hungarian). Magyar Nőorvosok Lapja [Journal of Hungarian Gynaecologists] 36: 433–442. 1973.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 "Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery". The New England Journal of Medicine 342 (20): 1500–7. May 2000. doi:10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. PMID 10816189.

- ↑ "Preterm birth due to maternal infection: Causative pathogens and modes of prevention". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 25 (9): 562–9. September 2006. doi:10.1007/s10096-006-0190-3. PMID 16953371.

- ↑ "Preterm premature rupture of the membranes". Obstetrics and Gynecology 101 (1): 178–93. January 2003. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02366-9. PMID 12517665.

- ↑ "Second-trimester loss and subsequent pregnancy outcomes: What is the real risk?". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 197 (6): 581.e1–6. December 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.016. PMID 18060941.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 Gynatren package insert. Hamburg, Germany: Strathmann GmbH & Co. KG; August 2017.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 "Heterovaccine against the trichomonas syndrome, and process for its preparation" US patent 4238478

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Gynevac package insert. Sajógalgóc, Hungary: Vakcina Kft.; July 2011.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Dauer der Schutzwirkung gegen Trichomoniasis nach Impfung mit SolcoTrichovac" (in German). Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (3): 191–6. January 1983. doi:10.1159/000269512. PMID 6642286.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 (in Hungarian) A Gynevac tündöklése és bukása? Dr. Újhelyi Károly harmadik védőoltásának története. Budapest: V and B Kommunikációs Kft.. 2017. ISBN 978-963-12-9519-1.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 43.5 "The ecologically wrong vaginal lactobacilli". Medical Hypotheses 36 (2): 126–130. October 1991. doi:10.1016/0306-9877(91)90253-U. PMID 1779915.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Bacterial non-specific vaginitis ('bacterial' vaginosis)". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 2–6. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269918. PMID 6537383.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 "New evidence elucidating the mechanism of action of Gynatren/SolcoTrichovac". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 29–37. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269923. PMID 6336149.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "IgA antibodies in the vaginal secretion after vaccination with SolcoTrichovac". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (Suppl 2): 46–9. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269594. PMID 6629135.

- ↑ "IgA antibody-producing cells in peripheral blood after antigen ingestion: evidence for a common mucosal immune system in humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 84 (8): 2449–53. April 1987. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.8.2449. PMID 3470804. Bibcode: 1987PNAS...84.2449C.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 "Chapter 95 - Mucosal Immunity in the Human Female Reproductive Tract". Mucosal Immunology (3rd ed.). Academic Press. 7 January 2005. pp. 1631–1646. doi:10.1016/B978-012491543-5/50099-1. ISBN 978-0-12-491543-5.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 "Induction of mucosal immune responses in the human genital tract". FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology 27 (4): 351–5. April 2000. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01449.x. PMID 10727891.

- ↑ "Immunoglobulin G antibodies in human vaginal secretions after parenteral vaccination". Infection and Immunity 62 (9): 3957–61. September 1994. doi:10.1128/IAI.62.9.3957-3961.1994. PMID 8063413.

- ↑ "A sensitive method for specific quantitation of secretory IgA". Scandinavian Journal of Immunology 6 (12): 1275–82. 1977. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.1977.tb00366.x. PMID 24264.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "Vaccine immunology". Plotkin's Vaccines (7th ed.). Elsevier. 2017. pp. 16–34. ISBN 978-0-323-35761-6.

- ↑ "Differential expression of tissue-specific adhesion molecules on human circulating antibody-forming cells after systemic, enteric, and nasal immunizations. A molecular basis for the compartmentalization of effector B cell responses". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 99 (6): 1281–6. March 1997. doi:10.1172/JCI119286. PMID 9077537.

- ↑ "Vaccination strategies for mucosal immune responses". Clinical Microbiology Reviews 14 (2): 430–45. April 2001. doi:10.1128/CMR.14.2.430-445.2001. PMID 11292646.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "Bacterial flora of the female genital tract: function and immune regulation". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 21 (3): 347–54. June 2007. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.004. PMID 17215167.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 "Changes in the vaginal flora of trichomoniasis patients after vaccination with SolcoTrichovac". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (Suppl 2): 50–5. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269596. PMID 6354887.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Therapie und Prophylaxe des unspezifischen Fluor vaginalis mit einer Laktobazillusvakzine" (in German). Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 23 (3): 205–207. 1983. doi:10.1159/000269691.

- ↑ "Trichomonas syndroma" (in Hungarian). Magyar Nőorvosok Lapja [Journal of Hungarian Gynaecologists] 37: 339–344. 1974.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Trichomoniasis. Scientific papers of the Symposium on Trichomoniasis. Basle, October 20, 1981". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau (Basle: Karger) 23 (Suppl 2): 1–91. 1983. doi:10.1159/isbn.978-3-318-01549-2. ISBN 978-3-8055-3751-3. PMID 6629130.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "Immunotherapy of Vaginal Infections. Scientific Papers Presented at the International Symposia in La Sarraz and Zurich, September 15 and 16, 1983". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau (Basle: Karger) 24 (Suppl 3): 1–92. 1984. doi:10.1159/isbn.978-3-318-01684-0. ISBN 978-3-8055-4072-8. PMID 6537381.

- ↑ "Lactobacillus vaginalis sp. nov. from the Human Vagina". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 39 (3): 368–370. 1989. doi:10.1099/00207713-39-3-368.

- ↑ "Hanseatisches Familienunternehmen mit Tradition" (in German). Strathmann GmbH & Co. KG. https://www.strathmann.de/index.php/en/historie.

- ↑ "Strovac und Gynatren — Impfungen mit amtlichem ATC-Code" (in German). MMW - Fortschritte der Medizin 155 (18): 73. October 2013.

- ↑ "GynVaccine - bei wiederkehrenden Beschwerden im Vaginalbereich" (in German). SymbioVaccin GmbH. https://www.symbiovaccin.de/patienteninfo/scheideninfektionen/.

- ↑ "Natürliche Hilfe bei Vaginose und Vulvovaginalkandidose − Mit Laktobazillen und GynVaccine die Döderleinflora stärken" (in German). Gyne 38 (3): 34–37. 2017. ISSN 0179-9185.

- ↑ "Prevalence of hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species in normal women and women with bacterial vaginosis". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 27 (2): 251–256. February 1989. doi:10.1128/jcm.27.2.251-256.1989. ISSN 0095-1137. PMID 2915019.

- ↑ "The Lactobacillus anomaly: total iron abstinence". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 40 (4): 578–583. January 1997. doi:10.1353/pbm.1997.0072. ISSN 0031-5982. PMID 9269745.

- ↑ "On the iron requirement of lactobacilli grown in chemically defined medium". Current Microbiology 37 (1): 64–66. July 1998. doi:10.1007/s002849900339. ISSN 0343-8651. PMID 9625793.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Lactobacillus iners, the unusual suspect". Research in Microbiology 168 (9–10): 826–836. September 2017. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2017.09.003. PMID 28951208.

- ↑ "Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis". The New England Journal of Medicine 353 (18): 1899–1911. November 2005. doi:10.1056/nejmoa043802. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 16267321.

- ↑ "The vaginal microbiome: new information about genital tract flora using molecular based techniques". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 118 (5): 533–549. January 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02840.x. ISSN 0306-5456. PMID 21251190.

- ↑ "Vaginal Microbiota". Microbiota of the Human Body. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 902 (1st ed.). Springer International Publishing. 2016. pp. 83–93. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31248-4_6. ISBN 978-3-319-31246-0.

- ↑ "Characterisation of the vaginal Lactobacillus microbiota associated with preterm delivery". Scientific Reports 4: 5136. May 2014. doi:10.1038/srep05136. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 24875844. Bibcode: 2014NatSR...4E5136P.

- ↑ "The interaction between vaginal microbiota, cervical length, and vaginal progesterone treatment for preterm birth risk". Microbiome 5 (1): 6. January 2017. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0223-9. ISSN 2049-2618. PMID 28103952.

- ↑ "Quantitative determination by real-time PCR of four vaginal Lactobacillus species, Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae indicates an inverse relationship between L. gasseri and L. iners". BMC Microbiology 7: 115. December 2007. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-7-115. ISSN 1471-2180. PMID 18093311.

- ↑ "Long, uniform Lactobacilli (Döderlein's Bacteria): a new risk factor for postoperative infection after first-trimester abortion". Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology 3 (3): 102–109. January 1995. doi:10.1155/s106474499500041x. ISSN 1064-7449. PMID 18476030.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "Cytolytic vaginosis". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 165 (4 Pt 2): 1245–1249. October 1991. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(12)90736-x. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 1951582.

- ↑ "Influence of vaginal bacteria and D- and L-lactic acid isomers on vaginal extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer: implications for protection against upper genital tract infections". mBio 4 (4). August 2013. doi:10.1128/mbio.00460-13. ISSN 2161-2129. PMID 23919998.

- ↑ "Probiotic agents to protect the urogenital tract against infection". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 73 (2 Suppl): 437S–443S. February 2001. doi:10.1093/ajcn/73.2.437s. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 11157354.

- ↑ "Lactobacilli at the front line of defense against vaginally acquired infections". Future Microbiology 6 (5): 567–582. 2011. doi:10.2217/fmb.11.36. ISSN 1746-0921. PMID 21585263.

- ↑ "S layer protein A of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM regulates immature dendritic cell and T cell functions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (49): 19474–19479. December 2008. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810305105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 19047644. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..10519474K.

- ↑ "Vaginal lactobacilli induce differentiation of monocytic precursors toward Langerhans-like cells: in vitro evidence". Frontiers in Immunology 9: 2437. October 2018. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02437. ISSN 1664-3224. PMID 30410487.

- ↑ "Inerolysin, a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin produced by Lactobacillus iners". Journal of Bacteriology 193 (5): 1034–1041. December 2010. doi:10.1128/jb.00694-10. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 21169489.

- ↑ "Inerolysin and vaginolysin, the cytolysins implicated in vaginal dysbiosis, differently impair molecular integrity of phospholipid membranes". Scientific Reports 9 (1): 10606. July 2019. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-47043-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 31337831. Bibcode: 2019NatSR...910606R.

- ↑ "Vaginal lactobacillosis". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 170 (3): 857–861. March 1994. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70298-5. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 8141216.

- ↑ "Normal and abnormal vaginal microbiota". Journal of Laboratory Medicine 40 (4): 239–246. January 2016. doi:10.1515/labmed-2016-0011. ISSN 0342-3026.

- ↑ "Candidiasis, Bacterial Vaginosis, Trichomoniasis and Other Vaginal Conditions Affecting the Vulva". Vulvar Disease (1st ed.). Springer, Cham. 2019. pp. 167–205. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-61621-6_24. ISBN 978-3-319-61620-9.

- ↑ "The adherence of Trichomonas vaginalis to host ectocervical cells is influenced by lactobacilli". Sexually Transmitted Infections 89 (6): 455–459. May 2013. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2013-051039. ISSN 1368-4973. PMID 23720602.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 "Mouse intravaginal infection with Trichomonas vaginalis and role of Lactobacillus acidophilus in sustaining infection". Infection and Immunity 60 (6): 2375–2379. June 1992. doi:10.1128/iai.60.6.2375-2379.1992. ISSN 0019-9567. PMID 1587604.

- ↑ "Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis". Obstetrics and Gynecology 99 (3): 419–425. March 2002. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01759-8. PMID 11864668.

- ↑ "Cultivation-independent analysis of changes in bacterial vaginosis flora following metronidazole treatment". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 45 (3): 1016–1018. January 2007. doi:10.1128/jcm.02085-06. ISSN 0095-1137. PMID 17202272.

- ↑ "Vaginal lactobacillosis". Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics 3 (3): 81–84. 2014. doi:10.14740/jcgo278e.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Wpływ T. vaginalis na fizjologiczna florę pochwy" (in Polish). Wiadomości Parazytologiczne 23 (5): 519–523. January 1977. ISSN 0043-5163. PMID 415437.

- ↑ "Microflora Associated with Trichomonas vaginalis and Vaccination Against Vaginal Trichomoniasis". Trichomonads Parasitic in Humans (1st ed.). Springer, New York, NY. 1990. pp. 213–224. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-3224-7_10. ISBN 978-1-4612-7922-8.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 "An explanation of the mode of action of Gynatren/SolcoTrichovac based on immunological considerations". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 25–8. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269922. PMID 6537384.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 "The destructive effect of SolcoTrichovac-induced serum antibodies on Trichomonas vaginalis; an electron microscopic investigation". Gynäkologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau 24 (Suppl 3): 38–43. 1984. doi:10.1159/000269924. PMID 6336150.

- ↑ "Does lactobacillus vaccine for trichomoniasis, Solco Trichovac, induce antibody reactive with Trichomonas vaginalis?". Genitourinary Medicine 64 (2): 118–23. April 1988. doi:10.1136/sti.64.2.118. PMID 3290091.

- ↑ "Immunotherapeutic effect of the lactobacillus vaccine, Solco Trichovac, in trichomoniasis is not mediated by antibodies cross reacting with Trichomonas vaginalis". Genitourinary Medicine 62 (2): 107–10. April 1986. doi:10.1136/sti.62.2.107. PMID 3522408.

- ↑ "A recently transferred cluster of bacterial genes in Trichomonas vaginalis--lateral gene transfer and the fate of acquired genes". BMC Evolutionary Biology 14: 119. June 2014. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-119. ISSN 1471-2148. PMID 24898731.

- ↑ "The protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis targets bacteria with laterally-acquired NlpC/P60 peptidoglycan hydrolases". mBio 9 (6). December 2018. doi:10.1128/mbio.01784-18. PMID 30538181.

- ↑ "Lateral gene transfer and metabolic adaptation in the human parasite Trichomonas vaginalis". Molecular Biology and Evolution 17 (11): 1769–73. November 2000. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026275. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 11070064.

- ↑ "Acute enteric infections alter commensal microbiota: new mechanisms in post-infectious intestinal inflammatory disorders". Old Herborn University Seminar Monograph: Persisting Consequences of Intestinal Infection 27: 87–100. 2014.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 103.2 103.3 "Functional flexibility of intestinal IgA - broadening the fine line". Frontiers in Immunology 3: 100. May 2012. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2012.00100. ISSN 1664-3224. PMID 22563329.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 "Life in the littoral zone: lactobacilli losing the plot". Sexually Transmitted Infections 81 (2): 100–102. April 2005. doi:10.1136/sti.2003.007161. ISSN 1368-4973. PMID 15800083.

- ↑ "Secretory IgA and mucin-mediated biofilm formation by environmental strains of Escherichia coli: role of type 1 pili". Molecular Immunology 43 (4): 378–387. February 2006. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2005.02.013. ISSN 0161-5890. PMID 16310051.

- ↑ "Gut microbiota utilize immunoglobulin A for mucosal colonization". Science 360 (6390): 795–800. May 2018. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0926. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29724905.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 107.2 107.3 "Roundtrip ticket for secretory IgA: role in mucosal homeostasis?". Journal of Immunology 178 (1): 27–32. January 2007. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.27. ISSN 0022-1767. PMID 17182536.

- ↑ "Human immature dendritic cells efficiently bind and take up secretory IgA without the induction of maturation". Journal of Immunology 168 (1): 102–107. January 2002. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.102. ISSN 0022-1767. PMID 11751952.

- ↑ "Molecular mechanisms of induction of tolerant and tolerogenic intestinal dendritic cells in mice". Journal of Immunology Research 2016: 1958650. February 2016. doi:10.1155/2016/1958650. ISSN 2314-8861. PMID 26981546.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 "Immune responses that adapt the intestinal mucosa to commensal intestinal bacteria". Immunology 115 (2): 153–162. June 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02159.x. ISSN 0019-2805. PMID 15885120.

- ↑ "IgA response to symbiotic bacteria as a mediator of gut homeostasis". Cell Host & Microbe 2 (5): 328–339. November 2007. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.013. ISSN 1931-3128. PMID 18005754.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 "Role of commensal gut bacteria in inflammatory bowel diseases". Gut Microbes 3 (6): 544–555. October 2012. doi:10.4161/gmic.22156. ISSN 1949-0984. PMID 23060017.

- ↑ "Identification of common vaginal Lactobacilli immunoreactive proteins by immunoproteomic techniques". World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology 35 (10): 161. October 2019. doi:10.1007/s11274-019-2736-4. ISSN 0959-3993. PMID 31608422.

- ↑ "Vaginal lactobacilli in adolescents: presence and relationship to local and systemic immunity, and to bacterial vaginosis". Sexually Transmitted Diseases 31 (7): 393–400. July 2004. doi:10.1097/01.OLQ.0000130454.83883.E9. ISSN 0148-5717. PMID 15215693.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 "Impairment of the mucosal immune system: IgA and IgM cleavage detected in vaginal washings of a subgroup of patients with bacterial vaginosis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 178 (6): 1698–1706. December 1998. doi:10.1086/314505. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 9815222.

- ↑ "Hydrolysis of secreted sialoglycoprotein immunoglobulin A (IgA) in ex vivo and biochemical models of bacterial vaginosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 287 (3): 2079–2089. December 2011. doi:10.1074/jbc.m111.278135. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 22134918.

External links

- "Recommendations to pregnant women suffering from recurrent bacterial vaginal infections (in German)". Erich Saling Institute of Perinatal Medicine. https://www.saling-institut.de/german/03infomo/04faq.html#WiederholtInf.

- "Old Herborn University: a knowledge hub of host-microbiota interaction, microbial preparations and autovaccines". https://www.old-herborn-university.de/.