Biology:Immunoglobulin E

Immunoglobulin E (IgE) is a type of antibody (or immunoglobulin (Ig) "isotype") that has been found only in mammals. IgE is synthesised by plasma cells. Monomers of IgE consist of two heavy chains (ε chain) and two light chains, with the ε chain containing four Ig-like constant domains (Cε1–Cε4).[1] IgE is thought to be an important part of the immune response against infection by certain parasitic worms, including Schistosoma mansoni, Trichinella spiralis,[2][3] and Fasciola hepatica.[4] IgE is also utilized during immune defense against certain protozoan parasites such as Plasmodium falciparum.[5] IgE may have evolved as a defense to protect against venoms.[6][7][8]

IgE also has an essential role in type I hypersensitivity,[9] which manifests in various allergic diseases, such as allergic asthma, most types of sinusitis, allergic rhinitis, food allergies, and specific types of chronic urticaria and atopic dermatitis. IgE also plays a pivotal role in responses to allergens, such as: anaphylactic reactions to drugs, bee stings, and antigen preparations used in desensitization immunotherapy.

Although IgE is typically the least abundant isotype—blood serum IgE levels in a normal ("non-atopic") individual are only 0.05% of the Ig concentration,[10] compared to 75% for the IgGs at 10 mg/ml, and are the isotypes responsible for most of the classical adaptive immune response—it is capable of triggering anaphylaxis, one of the most rapid and severe immunological reactions.[11]

Discovery

IgE was simultaneously discovered in 1966 and 1967 by two independent groups:[12] Kimishige Ishizaka and his wife Teruko Ishizaka at the Children's Asthma Research Institute and Hospital in Denver, Colorado,[13] and by Gunnar Johansson and Hans Bennich (sv) in Uppsala, Sweden.[14] Their joint paper was published in April 1969.[15]

Receptors

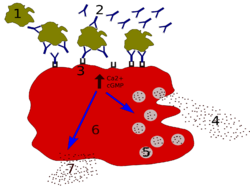

IgE primes the IgE-mediated allergic response by binding to Fc receptors found on the surface of mast cells and basophils. Fc receptors are also found on eosinophils, monocytes, macrophages and platelets in humans. There are two types of Fcε receptors:[citation needed]

- FcεRI (type I Fcε receptor), the high-affinity IgE receptor

- FcεRII (type II Fcε receptor), also known as CD23, the low-affinity IgE receptor

IgE can upregulate the expression of both types of Fcε receptors. FcεRI is expressed on mast cells, basophils, and the antigen-presenting dendritic cells in both mice and humans. Binding of antigens to IgE already bound by the FcεRI on mast cells causes cross-linking of the bound IgE and the aggregation of the underlying FcεRI, leading to degranulation (the release of mediators) and the secretion of several types of type 2 cytokines like interleukin (IL)-3 and stem cell factor (SCF), which both help the mast cells survive and accumulate in tissue, and IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-33, which in turn activate group 2-innate lymphoid cells (ILC2 or natural helper cells). Basophils share a common haemopoietic progenitor with mast cells; upon the cross-linking of their surface bound IgE by antigens, also release type 2 cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13, and other inflammatory mediators. The low-affinity receptor (FcεRII) is always expressed on B cells; but IL-4 can induce its expression on the surfaces of macrophages, eosinophils, platelets, and some T cells.[16][17]

Function

Parasite hypothesis

The IgE isotype has co-evolved with basophils and mast cells in the defence against parasites like helminths (like Schistosoma) but may be also effective in bacterial infections.[18] Epidemiological research shows that IgE level is increased when infected by Schistosoma mansoni,[19] Necator americanus,[20] and nematodes[21] in humans. It is most likely beneficial in removal of hookworms from the lung.[citation needed]

Toxin hypothesis of allergic disease

In 1981 Margie Profet suggested that allergic reactions have evolved as a last line of defense to protect against venoms.[6] Although controversial at the time, new work supports some of Profet’s thoughts on the adaptive role of allergies as a defense against noxious toxins.[7]

In 2013 it emerged that IgE-antibodies play an essential role in acquired resistance to honey bee[8] and Russell's viper venoms.[8][22] The authors concluded that "a small dose of bee venom conferred immunity to a much larger, fatal dose" and "this kind of venom-specific, IgE-associated, adaptive immune response developed, at least in evolutionary terms, to protect the host against potentially toxic amounts of venom, such as would happen if the animal encountered a whole nest of bees, or in the event of a snakebite".[8][23][24] The major allergen of bee venom (phospholipase A2) induces a Th2 immune responses, associated with production of IgE antibodies, which may "increase the resistance of mice to challenge with potentially lethal doses".[25]

Cancer

Although it is not yet well understood, IgE may play an important role in the immune system's recognition of cancer,[26] in which the stimulation of a strong cytotoxic response against cells displaying only small amounts of early cancer markers would be beneficial. If this were the case, anti-IgE treatments such as omalizumab (for allergies) might have some undesirable side effects. However, a recent study, which was performed based on pooled analysis using comprehensive data from 67 phase I to IV clinical trials of omalizumab in various indications, concluded that a causal relationship between omalizumab therapy and malignancy is unlikely.[27]

Role in disease

Atopic individuals can have up to ten times the normal level of IgE in their blood (as do sufferers of hyper-IgE syndrome). However, this may not be a requirement for symptoms to occur as has been seen in asthmatics with normal IgE levels in their blood—recent research has shown that IgE production can occur locally in the nasal mucosa.[28]

IgE that can specifically recognise an allergen (typically this is a protein, such as dust mite Der p 1, cat Fel d 1, grass or ragweed pollen, food protein, etc.) has a unique long-lived interaction with its high-affinity receptor FcεRI so that basophils and mast cells, capable of mediating inflammatory reactions, become "primed", ready to release chemicals like histamine, leukotrienes, and certain interleukins. These chemicals cause many of the symptoms we associate with allergy, such as airway constriction in asthma, local inflammation in eczema, increased mucus secretion in allergic rhinitis, and increased vascular permeability, it is presumed, to allow other immune cells to gain access to tissues, but which can lead to a potentially fatal drop in blood pressure as in anaphylaxis.[citation needed]

IgE is known to be elevated in various autoimmune disorders such as SLE, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and psoriasis, and is theorized to be of pathogenetic importance in SLE and RA by eliciting a hypersensitivity reaction.[29][30]

Regulation of IgE levels through control of B cell differentiation to antibody-secreting plasma cells is thought to involve the "low-affinity" receptor FcεRII, or CD23.[31] CD23 may also allow facilitated antigen presentation, an IgE-dependent mechanism whereby B cells expressing CD23 are able to present allergen to (and stimulate) specific T helper cells, causing the perpetuation of a Th2 response, one of the hallmarks of which is the production of more antibodies.[32]

Role in diagnosis

Diagnosis of allergy is most often done by reviewing a person's medical history and finding a positive result for the presence of allergen specific IgE when conducting a skin or blood test.[33] Specific IgE testing is the proven test for allergy detection; evidence does not show that indiscriminate IgE testing or testing for immunoglobulin G (IgG) can support allergy diagnosis.[34]

Drugs targeting the IgE pathway

Currently, allergic diseases and asthma are usually treated with one or more of the following drugs: (1) antihistamines and antileukotrienes, which antagonize the inflammatory mediators histamine and leukotrienes, (2) local or systemic (oral or injectable) corticosteroids, which suppress a broad spectrum of inflammatory mechanisms, (3) short or long-acting bronchodilators, which relax smooth muscle of constricted airway in asthma, or (4) mast cell stabilizers, which inhibit the degranulation of mast cells that is normally triggered by IgE-binding at FcεRI. Long-term uses of systemic corticosteroids are known to cause many serious side effects and are advisable to avoid, if alternative therapies are available.[citation needed]

IgE, the IgE synthesis pathway, and the IgE-mediated allergic/inflammatory pathway are all important targets in intervening with the pathological processes of allergy, asthma, and other IgE-mediated diseases. The B lymphocyte differentiation and maturation pathway that eventually generate IgE-secreting plasma cells go through the intermediate steps of IgE-expressing B lymphoblasts and involves the interaction with IgE-expressing memory B cells. Tanox, a biotech company based in Houston, Texas, proposed in 1987 that by targeting membrane-bound IgE (mIgE) on B lymphoblast and memory B cells, those cells can be lysed or down-regulated, thus achieving the inhibition of the production of antigen-specific IgE and hence a shift of immune balance toward non-IgE mechanisms.[35] Two approaches targeting the IgE pathway were evolved and both are in active development. In the first approach, the anti-IgE antibody drug omalizumab (trade name Xolair) recognises IgE not bound to its receptors and is used to neutralise or mop-up existing IgE and prevent it from binding to the receptors on mast cells and basophils. Xolair has been approved in many countries for treating severe, persistent allergic asthma. It has also been approved in March 2014 in the European Union[36] and the U. S.[37] for treating chronic spontaneous urticaria, which cannot be adequately treated with H1-antihistamines. In the second approach, antibodies specific for a domain of 52 amino acid residues, referred to as CεmX or M1’ (M1 prime), present only on human mIgE on B cells and not on free, soluble IgE, have been prepared and are under clinical development for the treatment of allergy and asthma.[38][39] An anti-M1’ humanized antibody, quilizumab, is in phase IIb clinical trial.[40][41]

In 2002, researchers at the Randall Division of Cell and Molecular Biophysics determined the structure of IgE.[42] Understanding of this structure (which is atypical of other isotypes in that it is highly bent and asymmetric) and of the interaction of IgE with receptor FcεRI will enable development of a new generation of allergy drugs that seek to interfere with the IgE-receptor interaction. It may be possible to design treatments cheaper than monoclonal antibodies (for instance, small molecule drugs) that use a similar approach to inhibit binding of IgE to its receptor.[citation needed]

References

- ↑ "Antibody structure". http://www.cartage.org.lb/en/themes/Sciences/LifeScience/GeneralBiology/Immunology/Recognition/AntigenRecognition/Antibodystructure/Antibodystructure.htm.

- ↑ "Helminths, allergic disorders and IgE-mediated immune responses: where do we stand?". European Journal of Immunology 37 (5): 1170–3. May 2007. doi:10.1002/eji.200737314. PMID 17447233.

- ↑ "IgE: a question of protective immunity in Trichinella spiralis infection". Trends in Parasitology 21 (4): 175–8. April 2005. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2005.02.010. PMID 15780839.

- ↑ "IgE production in rat fascioliasis". Parasite Immunology 5 (6): 587–93. November 1983. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3024.1983.tb00775.x. PMID 6657297.

- ↑ "Total and functional parasite specific IgE responses in Plasmodium falciparum-infected patients exhibiting different clinical status". Malaria Journal 6: 1. January 2007. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-6-1. PMID 17204149.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "The function of allergy: immunological defense against toxins". The Quarterly Review of Biology 66 (1): 23–62. March 1991. doi:10.1086/417049. PMID 2052671.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Allergic host defences". Nature 484 (7395): 465–72. April 2012. doi:10.1038/nature11047. PMID 22538607. Bibcode: 2012Natur.484..465P.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "A beneficial role for immunoglobulin E in host defense against honeybee venom" (in en). Immunity 39 (5): 963–75. November 2013. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.005. PMID 24210352.

- ↑ "The biology of IGE and the basis of allergic disease". Annual Review of Immunology 21: 579–628. 2003. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141103. PMID 12500981.

- ↑ "Immunoglobulin E: importance in parasitic infections and hypersensitivity responses". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 124 (9): 1382–5. September 2000. doi:10.5858/2000-124-1382-IE. PMID 10975945.

- ↑ Reber, LL; Hernandez, JD; Galli, SJ (August 2017). "The pathophysiology of anaphylaxis.". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 140 (2): 335–348. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.003. PMID 28780941.

- ↑ "The discovery of IgE". Allergy 48 (2): 67–71. February 1993. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1993.tb00687.x. PMID 8457034.

- ↑ "Physico-chemical properties of human reaginic antibody. IV. Presence of a unique immunoglobulin as a carrier of reaginic activity". Journal of Immunology 97 (1): 75–85. July 1966. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.97.1.75. PMID 4162440.

- ↑ "Immunological studies of an atypical (myeloma) immunoglobulin". Immunology 13 (4): 381–94. October 1967. PMID 4168094.

- ↑ "Histamine release from human leukocytes by anti-gamma E antibodies". Journal of Immunology 102 (4): 884–92. April 1969. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.102.4.884. PMID 4181251. http://www.jimmunol.org/content/102/4/884.abstract. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- ↑ "The CD23a and CD23b proximal promoters display different sensitivities to exogenous stimuli in B lymphocytes". Genes and Immunity 3 (3): 158–64. May 2002. doi:10.1038/sj.gene.6363848. PMID 12070780.

- ↑ "IgE receptors". Current Opinion in Immunology 13 (6): 721–6. December 2001. doi:10.1016/s0952-7915(01)00285-0. PMID 11677096.

- ↑ Abraham, Soman N.; St. John, Ashley L. (June 2010). "Mast cell-orchestrated immunity to pathogens" (in en). Nature Reviews Immunology 10 (6): 440–452. doi:10.1038/nri2782. ISSN 1474-1741. PMID 20498670.

- ↑ "Evidence for an association between human resistance to Schistosoma mansoni and high anti-larval IgE levels". European Journal of Immunology 21 (11): 2679–86. November 1991. doi:10.1002/eji.1830211106. PMID 1936116.

- ↑ "Immunity in humans to Necator americanus: IgE, parasite weight and fecundity". Parasite Immunology 17 (2): 71–5. February 1995. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3024.1995.tb00968.x. PMID 7761110.

- ↑ "Allergen-specific IgE and IgG4 are markers of resistance and susceptibility in a human intestinal nematode infection". Microbes and Infection 7 (7–8): 990–6. June 2005. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2005.03.036. PMID 15961339.

- ↑ "IgE antibodies, FcεRIα, and IgE-mediated local anaphylaxis can limit snake venom toxicity". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 137 (1): 246–257.e11. January 2016. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.005. PMID 26410782.

- ↑ Sharlach, Molly (24 October 2013). "Bee sting allergy could be a defense response gone haywire, scientists say". http://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2013/10/bee-sting-allergy-could-be-a-defense-response-gone-haywire-scientists-say.html.

- ↑ Foley, James A. (25 October 2013). "Severe Allergies to Bee Stings may be Malfunctioning Evolutionary Response". Nature World News. https://www.natureworldnews.com/articles/4618/20131025/severe-allergies-bee-stings-malfunctioning-evolutionary-response.htm.

- ↑ "Testing the 'toxin hypothesis of allergy': mast cells, IgE, and innate and acquired immune responses to venoms". Current Opinion in Immunology 36: 80–7. October 2015. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2015.07.001. PMID 26210895.

- ↑ "Activity of human monocytes in IgE antibody-dependent surveillance and killing of ovarian tumor cells". European Journal of Immunology 33 (4): 1030–40. April 2003. doi:10.1002/eji.200323185. PMID 12672069.

- ↑ "Omalizumab and the risk of malignancy: results from a pooled analysis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 129 (4): 983–9.e6. April 2012. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.033. PMID 22365654.

- ↑ "Allergen drives class switching to IgE in the nasal mucosa in allergic rhinitis". Journal of Immunology 174 (8): 5024–32. April 2005. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5024. PMID 15814733.

- ↑ "The prevalence of IgE antinuclear antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus". Acta Pathologica et Microbiologica Scandinavica, Section C 86C (5): 245–9. October 1978. doi:10.1111/j.1699-0463.1978.tb02587.x. PMID 309705.

- ↑ "Serum IgE concentrations, disease activity, and atopic disorders in systemic lupus erythematosus". Allergy 50 (1): 94–6. January 1995. PMID 7741196.

- ↑ "CD23: an overlooked regulator of allergic disease". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 7 (5): 331–7. September 2007. doi:10.1007/s11882-007-0050-y. PMID 17697638.

- ↑ "Facilitated antigen presentation and its inhibition by blocking IgG antibodies depends on IgE repertoire complexity". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 127 (4): 1029–37. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.062. PMID 21377718.

- ↑ "Pearls and pitfalls of allergy diagnostic testing: report from the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Specific IgE Test Task Force". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 101 (6): 580–92. December 2008. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60220-7. PMID 19119701.

- ↑ American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. http://choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/5things_12_factsheet_AAAAI.pdf. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ↑ Anti‐IgE Antibodies for the Treatment of IgE‐Mediated Allergic Diseases. Advances in Immunology. 93. 2007. pp. 63–119. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(06)93002-8. ISBN 9780123737076.

- ↑ "Novartis announces Xolair® approved in EU as first and only licensed therapy for chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) patients unresponsive to antihistamines". Novartis. 2014-03-06. http://www.novartis.com/newsroom/media-releases/en/2014/1766627.shtml.

- ↑ "Novartis announces US FDA approval of Xolair® for chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU)". Novartis. 2014-03-21. http://www.novartis.com/newsroom/media-releases/en/2014/1770973.shtml.

- ↑ "Unique epitopes on C epsilon mX in IgE-B cell receptors are potentially applicable for targeting IgE-committed B cells". Journal of Immunology 184 (4): 1748–56. February 2010. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0902437. PMID 20083663.

- ↑ "Antibodies specific for a segment of human membrane IgE deplete IgE-producing B cells in humanized mice". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 120 (6): 2218–29. June 2010. doi:10.1172/JCI40141. PMID 20458139.

- ↑ "MEMP1972A". U.S. National Institutes of Health. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=MEMP1972A.

- ↑ "Targeting membrane-expressed IgE B cell receptor with an antibody to the M1 prime epitope reduces IgE production". Science Translational Medicine 6 (243): 243ra85. July 2014. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3008961. PMID 24990880.

- ↑ "The crystal structure of IgE Fc reveals an asymmetrically bent conformation". Nature Immunology 3 (7): 681–6. July 2002. doi:10.1038/ni811. PMID 12068291.

|