Medicine:Polycythemia vera

| Polycythemia vera | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Polycythaemia vera (PV, PCV), erythremia, primary polycythemia, Vaquez disease, Osler-Vaquez disease, polycythemia rubra vera[1] |

| |

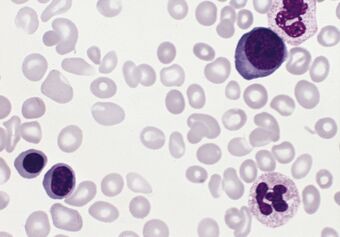

| Blood smear from a patient with polycythemia vera | |

| Specialty | Oncology, hematology |

In oncology, polycythemia vera (PV) is an uncommon myeloproliferative neoplasm in which the bone marrow makes too many red blood cells.[1] Approximately 98%[2][3] of PV patients have a JAK2 gene mutation in their blood-forming cells[4][5] (compared with 0.1-0.2% of the general population).[6][7]

Most of the health concerns associated with PV, such as thrombosis, are caused by the blood being thicker as a result of the increased red blood cells.

PV may be asymptomatic. Possible symptoms, if any do occur, include fatigue, itching (pruritus), particularly after exposure to warm water, and severe burning pain in the hands or feet that is usually accompanied by a reddish or bluish coloration of the skin.

Treatment consists primarily of blood withdrawals (phlebotomy) and oral meds.

PV is more common in the elderly.

Classification

PV is code 2A20.4 in the ICD-11.[8] It is a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN).[9] It is a primary form of polycythemia.

Pathophysiology

Approximately 98%[2][3] of PV patients have a mutation in a tyrosine kinase–encoding gene, JAK2, in their blood-forming cells[4][5] (compared with 0.1-0.2% of the general population).[6][7]

This acts in signaling pathways of the EPO receptor, making those cells proliferate independently from EPO. PV is associated with a low serum level of the hormone erythropoietin (EPO), in contrast to secondary polycythemias.[10][page needed]

While the mutation is a JAK2 V617F in 95% of patients, JAK2 exon 12 mutations have also been observed.[11]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms

People with PV can be asymptomatic.[12]

Possible symptoms of PV[13][14] that may aid identification include;

- pruritus (itching), particularly after exposure to warm water (such as when taking a bath),[15] which may be due to abnormal histamine release[16][17] or prostaglandin production.[18] Such itching is present in 40%-55% of patients with PV.[19][20]

- erythromelalgia,[21] a burning pain in the hands or feet, usually accompanied by a reddish or bluish coloration of the skin. Erythromelalgia is caused by an increased platelet count or increased platelet "stickiness" (aggregation), resulting in the formation of tiny blood clots in the vessels of the extremity; it responds rapidly to treatment with aspirin.[22][23]

Other possible symptoms of PV include night sweats and fatigue.[13][14]

No symptoms are required for diagnosis.

Other diseases that may be present with PV

Other diseases that may be present with PV include;

- An enlarged spleen, a manageable condition, may occur[24] and may cause the spleen to be palpable in some patients. This may be associated with both the V617F mutation and the development of myelofibrosis.[25]

- Swollen joints (Gout)[24]

- Peptic ulcers.[24]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria

WHO 2016

Diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera were modified by the World Health Organization in 2016.[26]

There are 3 major criteria for PV diagnosis:

- A very high red blood cell count, which is usually identified by elevated levels of hemoglobin or hematocrit;

- A bone marrow biopsy that shows hypercellularity and abnormalities in megakaryocytes; and

- The presence of a mutation in the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) gene.

A minor diagnostic feature is that patients usually have a very low level of erythropoietin (EPO), a growth factor that increases the production of red blood cells.[27][11] This is used to detect cases which are negative for JAK2 mutation.[28]

Reviews 2023-25

As of 2025, reviews state diagnosis can be based on

- the presence of a JAK2 mutation and

- hemoglobin/hematocrit levels of >16.5 g/dL/49% in men or 16 g/dL/48% in women.

Bone marrow morphologic confirmation is advised but not mandated.[29][30]

Outlook and prognosis

Prognosis

PV may remain stable for many years, with no effect on life expectancy, particularly if managed effectively.[31] Studies show the median survival rate of controlled PV ranges from 10 to 20 years but most observations are of people diagnosed in their 60s. Patients live close to a normal life expectancy,[11] but overall survival in PV is below that of age- and sex-matched general population.[32] Factors predicting this may include age and detailed genetic differences.[32]

Possible complications and developments

PV may cause blood clotting complications (thrombosis),[33] with the two main risk factors being a previous clot or clots, and age (60 years or older).[34] If PV is untreated, there is a substantial risk of Budd-Chiari syndrome (a hepatic vein thrombosis).[35]

PV may develop into myelofibrosis (a rare bone marrow cancer) or acute myeloid leukemia.[31][36][30]

Bleeding is a possible PV complication, although major bleeds are rare.[30]

Treatment and management

Overview

As of 2024 a cure for PV has not been found.[32][30]

The treatment goal is to prevent thrombosis.

The "backbone" of treatment, regardless of risk category, if there are no contraindications, is;

- Periodic blood withdrawals (phlebotomy), to keep hematocrit level below 45%, and

- daily (or twice daily) aspirin (81 mg).[32][30]

Additional management, depending on risks appraisal,[32][30] may include meds.[37]

A secondary treatment goal is to alleviate symptoms, for instance of pruritus (itching).[32][30]

Blood withdrawals

Blood withdrawal, sometimes called phlebotomy or venesection, is a process similar to donating blood[38] and helps to keep haematocrit levels low. This might be done weekly initially, and less often over time.[37]

Meds

Aspirin may be taken, to reduce thrombosis risk, regardless of risk category.[32]

Other medications may be used;

- Hydroxyurea reduces adverse cell development. Side effects include a small increase in the risk of developing a leukaemia. Ruxolitinib (brand name Jakafi), a JAK2 inhibitor, and Busulfan may be used as alternatives.[39]

- Ropeginterferon alfa-2b (Besremi) reduces the rate of blood cell production,[40][41][42] and can be used regardless of treatment history.[41] Interferon alfa-2b is also used.[43]

- Anagrelide with other cytoreductive drugs may be used to manage platelet levels.[37][44]

Erlotinib may be an additional treatment option for those with certain genetic markers.[45]

Allopurinol may be used to manage gout.[37]

Lifestyle

A healthy lifestyle, including no smoking and avoidance of excessive weight, is also recommended.[37]

Specialist care

A hematologist may be involved in the care of patients with PV.[30]

Managing itching, if present

Ideas for managing itching include trying cooler showers and baths.[34][46]

Managing emotional and practical effects

Patient education and patient forums can help patients practically and emotionally manage a PV diagnosis, symptoms and other practical considerations.[36][47]

Epidemiology

Polycythemia vera occurs in all age groups,[48] although the incidence increases with age. One study found the median age at diagnosis to be 60 years,[19] and another that the highest incidence was in people aged 70–79 years.[49] 10% of PV patients are below age 40 years.[32]

Overall incidences in population studies have been 1.9/100,000 person-years in a Minnesota study,[49] and 1.48/100,000 person-years in an age-standardized Swedish study (n = 6281).[32] PV can impact all ethnic groups. There are slightly more cases in men than women.[30][49]

A cluster around a toxic site was confirmed in northeast Pennsylvania in 2008.[50]

While the JAK2 V617F mutation is generally sporadic (random), a certain inherited haplotype of JAK2 has been associated with its development.[20][51]

Notable cases

Notable people living with PV include:

- Juan Alderete

- Will Self

Few notable deaths have been attributed to PV. Instances (all aged 56 or older) are

- Alessandro Di Fiore (1965-2021), Italian entrepreneur.

- Phyllis George (1949–2020), American sportscaster and former First Lady of Kentucky[52]

- Chet Lemon (1955-2025), American baseball player[53]

- Ron Miles (1963–2022), American jazz trumpeter[54]

- Nell Rankin (1924–2005), American mezzo-soprano[55]

History

Figures in the discovery of and development of treatment for PV include William Osler and Louis Henri Vaquez.[56] Historically PV was called Osler–Vaquez disease.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "polycythemia vera." at Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 21 Sep. 2010

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Regimbeau, M.; Mary, R.; Hermetet, F.; Girodon, F. (2022). "Genetic Background of Polycythemia Vera". Genes 13 (4): 637. doi:10.3390/genes13040637. PMID 35456443.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Polycythemia Vera (PV) – MPN Research Foundation". https://mpnresearchfoundation.org/polycythemia-vera-pv/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Targeted deep sequencing in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocytopenia". Blood Advances 1 (1): 21–30. 2016. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2016000216. PMID 29296692.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Most commonly resulting in a single amino acid change in its protein product from valine to phenylalanine at position 617."Genetic Background of Polycythemia Vera". Genes 13 (4): 637. 2022. doi:10.3390/genes13040637. PMID 35456443.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Nielsen, C.; Bojesen, S. E.; Nordestgaard, B. G.; Kofoed, K. F.; Birgens, H. S. (2014). "JAK2V617F somatic mutation in the general population: Myeloproliferative neoplasm development and progression rate". Haematologica 99 (9): 1448–1455. doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.107631. PMID 24907356.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Nielsen, C.; Birgens, H. S.; Nordestgaard, B. G.; Kjær, L.; Bojesen, S. E. (2010). "The JAK2 V617F somatic mutation, mortality and cancer risk in the general population". Haematologica 96 (3): 450–453. doi:10.3324/haematol.2010.033191. PMID 21160067.

- ↑ "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". https://icd.who.int/browse/2025-01/mms/en#818364947.

- ↑ "Myeloproliferative Neoplasms | Leukemia and Lymphoma Society". https://www.lls.org/myeloproliferative-neoplasms.

- ↑ Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. 2007. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Verstovsek, S. (2016). "Highlights in polycythemia vera from the 2016 EHA congress". Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 14 (10): 810–813. PMID 27930632. https://www.hematologyandoncology.net/archives/october-2016/highlights-in-polycythemia-vera-from-the-2016-eha-congres/.

- ↑ [Polycythemia vera EBSCO database] verified by URAC; accessed from Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Signs and Symptoms | Leukemia and Lymphoma Society". https://www.lls.org/myeloproliferative-neoplasms/polycythemia-vera/signs-and-symptoms.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "What is polycythaemia vera (PV)?". https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/polycythaemia-vera/what-is-pv.

- ↑ "Polycythemia vera-associated pruritus and its management". Eur J Clin Invest 40 (9): 828–34. 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02334.x. PMID 20597963.

- ↑ "Polycythaemia rubra vera and water-induced pruritus: blood histamine levels and cutaneous fibrinolytic activity before and after water challenge". Br J Dermatol 116 (3): 329–33. 1987. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb05846.x. PMID 3567071.

- ↑ "Skin mast cells in polycythaemia vera: relationship to the pathogenesis and treatment of pruritus". Br J Dermatol 116 (1): 21–9. 1987. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb05787.x. PMID 3814512.

- ↑ "Pruritus in polycythemia vera: treatment with aspirin and possibility of platelet involvement". Acta Derm Venereol 59 (6): 505–12. 1979. doi:10.2340/0001555559505512. PMID 94209.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Berlin NI (1975). "Diagnosis and classification of polycythemias". Semin Hematol 12 (4): 339–51. PMID 1198126.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "JAK2 haplotype is a major risk factor for the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms". Nature Genetics 41 (4): 446–449. 2009. doi:10.1038/ng.334. PMID 19287382.

- ↑ "Erythromelalgia: a pathognomonic microvascular thrombotic complication in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera". Semin Thromb Hemost 23 (4): 357–63. 1997. doi:10.1055/s-2007-996109. PMID 9263352.

- ↑ Michiels J (1997). "Erythromelalgia and vascular complications in polycythemia vera". Semin Thromb Hemost 23 (5): 441–54. doi:10.1055/s-2007-996121. PMID 9387203.

- ↑ "Increased thromboxane biosynthesis in patients with polycythemia vera: evidence for aspirin-suppressible platelet activation in vivo". Blood 80 (8): 1965–71. 1992. doi:10.1182/blood.V80.8.1965.1965. PMID 1327286.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Polycythemia vera-Polycythemia vera - Symptoms & causes". https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/polycythemia-vera/symptoms-causes/syc-20355850.

- ↑ "Volumetric Splenomegaly in Patients With Polycythemia Vera". Journal of Korean Medical Science 37 (11). 2022. doi:10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e87. PMID 35315598.

- ↑ Daniel A. Arber; Attilio Orazi; Robert Hasserjian; Jürgen Thiele; Michael J. Borowitz; Michelle M. Le Beau; Clara D. Bloomfield; Mario Cazzola et al. (2016). "The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia". Blood 127 (20): 2391–2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. PMID 27069254. The WHO criteria for polycythemia vera are specifically outlined in Table 4.

- ↑ "Hematocrit Levels | HCT Blood Test For Blood Cancer | LLS". https://www.lls.org/myeloproliferative-neoplasms/polycythemia-vera/diagnosis.

- ↑ https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7326849/

- ↑ Tefferi, Ayalew; Barbui, Tiziano (September 5, 2023). "Polycythemia vera: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management". American Journal of Hematology 98 (9): 1465–1487. doi:10.1002/ajh.27002. PMID 37357958.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 30.8 Lu, Xiao; Chang, Richard (June 5, 2025). "Polycythemia Vera". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557660/.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Treatment Outcomes | Leukemia and Lymphoma Society". https://www.lls.org/myeloproliferative-neoplasms/polycythemia-vera/treatment/treatment-outcomes.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 32.8 Tefferi, Ayalew; Barbui, Tiziano (Jun 5, 2023). "Polycythemia vera: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management". American Journal of Hematology 98 (9): 1465–1487. doi:10.1002/ajh.27002. PMID 37357958. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajh.27002.

- ↑ "Disease Complications | Leukemia and Lymphoma Society". https://www.lls.org/myeloproliferative-neoplasms/polycythemia-vera/disease-complications.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Treatment | Leukemia and Lymphoma Society". https://www.lls.org/myeloproliferative-neoplasms/polycythemia-vera/treatment.

- ↑ "Elevated serum erythropoietin levels in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome secondary to polycythemia vera: clinical implications for the role of JAK2 mutation analysis". Eur. J. Haematol. 77 (1): 57–60. July 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2006.00667.x. PMID 16827884.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Research and coping with polycythaemia vera (PV)". https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/polycythaemia-vera/research-coping.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 "Tests and treatment for polycythaemia vera (PV)". https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/polycythaemia-vera/tests-treatment.

- ↑ "Polycythemia Vera: What It Is, Symptoms & Treatment". https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17742-polycythemia-vera.

- ↑ Tefferi, A; Vannucchi, AM; Barbui, T (10 January 2018). "Polycythemia vera treatment algorithm 2018.". Blood Cancer Journal 8 (1): 3. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0042-7. PMID 29321547.

- ↑ "Besremi EPAR". 12 December 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/besremi.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "FDA Approves Treatment for Rare Blood Disease". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 12 November 2021. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "U.S. FDA Approves Besremi (ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft) as the Only Interferon for Adults With Polycythemia Vera" (Press release). PharmaEssentia. 12 November 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021 – via Business Wire.

- ↑ "Polycythemia vera - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/polycythemia-vera/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20355855.

- ↑ "Polycythemia vera-Polycythemia vera - Diagnosis & treatment". https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/polycythemia-vera/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20355855.

- ↑ "Erlotinib Effectively Inhibits JAK2V617F Activity and Polycythemia Vera Cell Growth". J Biol Chem 282 (6): 3428–32. 2007. doi:10.1074/jbc.C600277200. PMID 17178722.

- ↑ "Blood Cancer UK | Looking after yourself with PV". https://bloodcancer.org.uk/understanding-blood-cancer/polycythaemia-vera-pv/looking-after-yourself-with-pv/#managing-itching.

- ↑ "Polycythaemia vera (PV) - Macmillan Cancer Support". https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/blood-cancer/polycythaemia-vera-pv.

- ↑ "Polycythemia vera in young patients: a study on the long-term risk of thrombosis, myelofibrosis and leukemia". Haematologica 88 (1): 13–8. 2003. PMID 12551821.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 "Trends in the incidence of polycythemia vera among Olmsted County, Minnesota residents, 1935-1989". Am J Hematol 47 (2): 89–93. 1994. doi:10.1002/ajh.2830470205. PMID 8092146.

- ↑ MICHAEL RUBINKAM (2008). "Cancer cluster confirmed in northeast Pennsylvania". Associated Press. https://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20080826/ap_on_sc/toxic_dump_fears.

- ↑ "Whole-exome sequencing identifies novel candidate predisposition genes for familial polycythemia vera". Human Genomics 11 (1). 2017. doi:10.1186/s40246-017-0102-x. PMID 28427458.

- ↑ Yetter, Deborah (May 16, 2020). "Phyllis George, former Kentucky first lady and Miss America, dies at 70". The Courier-Journal. https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/local/2020/05/16/former-miss-america-kentucky-first-lady-phyllis-george-dies/3051644001/.

- ↑ Jeff Seidel; Evan Petzold (May 8, 2025). "Chet Lemon, 1984 Detroit Tigers hero, dies at age 70". Detroit Free Press. https://www.freep.com/story/sports/mlb/tigers/2025/05/08/chet-lemon-death-age-tigers-1984/83513931007/.

- ↑ Harrington, Jim (March 9, 2022). "'Gifted artist' Ron Miles dies of a rare blood disorder at 58". The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2022/03/09/gifted-artist-ron-miles-dies-of-a-rare-blood-disorder-at-58/.

- ↑ Allan Kozinn (January 19, 2005). "Nell Rankin Is Dead at 81; Mezzo-Soprano with Met". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/19/arts/music/19rankin.html.

- ↑ Berlin, N. I.; Wasserman, L. R. (Oct 25, 1997). "Polycythemia vera: a retrospective and reprise". The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine 130 (4): 365–373. doi:10.1016/s0022-2143(97)90035-4. PMID 9358074.

External links

- Polycythemia Vera at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- 11-141d. at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|