Medicine:Work–life interface

Work–life interface is the intersection of work and personal life. There are many aspects of one's personal life that can intersect with work including family, leisure, and health. Work–life interface is bidirectional; for instance, work can interfere with private life, and private life can interfere with work. This interface can be adverse in nature (e.g., work-life conflict) or can be beneficial (e.g., work-life enrichment) in nature.[1] Recent research has shown that the work–life interface is becoming increasingly boundaryless, especially for technology-enabled workers.[2]

Dominant theories of the relationship

Several theories explain different aspects of the relationship between the work and family life. Boundary theory and border theory are the two fundamental theories that researchers have used to study these role conflicts. Other theories are built on the foundations of these two theories. In the two decades since boundary theory and border theory were first proposed, the rise of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) has drastically altered the work–life interface.[3] Work can now be completed at any time and in any location, meaning that domains are more likely to be blended and boundaries barely exist.[4]

Seven dominant theories have been utilized to explain this relationship on the boundary-border spectrum; These theories are: structural functioning, segmentation, compensation, supplemental and reactive compensation, role enhancement, spillover, and work enrichment model.[5]

Structural functionalism

The roots of this theory can be traced back to the early 20th century, when industrial revolution was separating economic work from the family home. The 19th century’s technological advancements in machinery and manufacturing initiated the separation of work from family. However, it was not until the early 20th century that the first view of work-family theories started to shape. Structural-functionalism as one of the dominant sociology theories of early 20th century was a natural candidate. The structural functionalism theory, which emerged following WWII, was largely influenced from the industrial revolution and the changes in the social role of men and women during this period. This theory implies that the life is concerned mainly with two separate spheres: productive life which happens in the workplace and affective life which is at home. Structural functionalism theory believes in the existence of radical separation between work (institution, workplace, or market) and families. According to this theory, these two (workplace and family) work best "when men and women specialize their activities in separate spheres, women at home doing expressive work and men in the workplace performing instrumental tasks” (Kingsbury & Scanzoni, 1993; as cited in MacDermid, 2005: 18).

Greedy institutions

It has been argued that the work-family conflicts, in particular role conflicts, can be interpreted in terms of Lewis A. Coser's concept of "greedy institutions". These institutions are called "greedy" in the sense that they make all-encompassing demands on the commitment and loyalty of individuals, and tend to discourage involvement in other social spheres.[6][7][8] Institutions such as religious orders, sects, academia, top level sports, the military and senior management have been interpreted as greedy institutions. On the other hand, also the family has been interpreted as a greedy institution in consideration of the demands placed on a caretaker.[9][10] When a person is involved in two greedy institutions – be it child care and university, or family and the military,[11] or others − task and role conflicts arise.

Segmentation

Based on this theory work and family do not affect each other, since they are segmented and independent from each other.[5] The literature also reports the usage of the terms compartmentalization, independence, separateness, disengagement, neutrality, and detachment to describe this theory.[12]

Compensation

In 1979, Piotrkowski argued that according to this theory employees “look to their homes as havens, [and] look to their families as sources of satisfaction lacking in the occupational sphere."[5] What distinguishes compensation theory from the previous theories is that, in compensation theory, for the first time, the positive effect of work to family has been recognized.

Supplemental and reactive compensation

Supplemental and reactive compensation theories are two dichotomies of compensation theory which were developed during the late 1980s and the early 1990s. While compensation theory describes the behavior of employees in pursuing an alternative reward in the other sphere, supplemental and reactive compensation theories try to describe the reason behind the work-family compensation behavior of employees.

Role enhancement theory

According to this theory, the combination of certain roles has a positive, rather than a negative effect on well-being. This theory states that participation in one role is made better or easier by virtue of participation in the other role. Moreover, this theory acknowledges the negative effect of the work-family relationship, in which, only beyond a certain upper limit may overload and distress occur, however, the central focus of this perspective is mainly on the positive effects of work and family relationship, such as resource enhancement.

Spillover

Spillover is a process by which an employee’s experience in one domain affects their experience in another domain. Theoretically, spillover is perceived to be one of two types: positive or negative. Spillover as the most popular view of relationship between work and family, considers multidimensional aspects of work and family relationship.

Work enrichment model

This theory is one of the recent models for explaining the relationship between work and family. According to this model, experience in one role (work or family) will enhance the quality of life in the other role. In other words, this model tries to explain the positive effects of the work-family relationship.

Work–family conflict

Work and family studies historically focus on studying the conflict between different roles that individuals have in their society, specifically their roles at work, and their roles as a family member.[5]

Work–family conflict is defined as interrole conflict where the participation in one role interfere with the participation in another. Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) differentiate three sources for conflict between work and family:

- "time devoted to the requirements of one role makes it difficult to fulfill requirements of another" (p. 76);

- "strain from participation in one role makes it difficult to fulfill requirements of another" (p. 76);

- "specific behaviors required by one role make it difficult to fulfill the requirements of another" (p. 76).

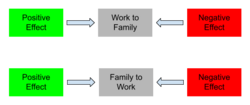

Conceptually, the conflict between work and family is bi-directional. Scholars distinguish between what is termed work-to-family conflict (WFC), and what is termed family-to-work conflict (FWC). This bi-directional view is displayed in the figure on the right.

Accordingly, WFC might occur when experiences at work interfere with family life like extensive, irregular, or inflexible work hours. Family-to-work conflict occurs when experiences in the family interfere with work life. For example, a parent may take time off from work in order to take care of a sick child. Although these two forms of conflict — WFC and FWC — are strongly correlated with each other, more attention has been directed at WFC. This may because family demands are more elastic than the boundaries and responsibilities of the work role. Also, research has found that work roles are more likely to interfere with family roles than family roles are likely to interfere with work roles.

Allen, Herst, Bruck, and Sutton (2000)[5] describe in their paper three categories of consequences related to WFC: work-related outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction or job performance), nonwork-related outcomes (e.g., life or family satisfaction), and stress-related outcomes (e.g., depression or substance abuse). For example, WFC has been shown to be negatively related to job satisfaction whereas the association is more pronounced for females.[13]

The vast majority of studies investigating the consequences of WFC were interrogating samples from Western countries, such as U.S. Therefore, the generalizability of their findings is in question. Fortunately, there is also literature studying WFC and its consequences in other cultural contexts, such as Taiwan[14] and India .[15] Lu, Kao, Cooper, Allen, Lapierre, O`Driscoll, Poelmans, Sanchez, and Spector (2009) could not find any cultural difference related in work-related and nonwork-related outcomes of WFC when they compared Great Britain and Taiwan. Likewise, Pal and Saksvik (2008) also did not detect specific cultural differences between employees from Norway and India. Nevertheless, more cross-cultural research is needed to understand the cultural dimensions of the WFC construct.

The research concerning interventions to reduce WFC is currently still very limited. As an exception, Nielson, Carlson, and Lankau (2001)[16] showed that having a supportive mentor on the job correlates negatively with the employee’s WFC. However, other functions of mentoring, like the role model aspect, appear to have no effect on WFC. Therefore, the mechanisms how having a mentor influences the work–family interface remain unclear.

In terms of primary and secondary intervention there are some results. Hammer, Kossek, Anger, Bodner, and Zimmerman (2011)[17] conducted a field study and showed that training supervisors to show more family supportive behavior, led to increased physical health in employees that were high in WFC. At the same time, employees having low WFC scores even decreased in physical health. This shows that even though interventions can help, it is important to focus on the right persons. Otherwise, the intervention damages more than it helps. Another study (Wilson, Polzer-Debruyne, Chen, & Fernandes, 2007)[18] showed that training employees helps to reduce shift work related WFC. Additionally, this training is more effective, if the partner of the focal person is also participating. Therefore, integrating the family into the intervention seems to be helpful too. There are various additional factors that might influence the effectiveness of WFC interventions. For example, some interventions seem more adequate to reduce family-to-work conflict (FWC) than WFC (Hammer et al., 2011). More research is still needed, before optimal treatments against WFC can be derived.

Work–family enrichment

Work–family enrichment or work–family facilitation is a form of positive spillover, defined as a process whereby involvement in one domain establishes benefits and/or resources which then may improve performance or involvement in another domain (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006).[19] For example, involvement in the family role is made easier by participation in the work role (Wayne, Musisca, & Fleeson, 2004).[20]

In contrast to work–family conflict which is associated with several negative consequences, work–family enrichment is related to positive organizational outcomes such as job satisfaction and effort (Wayne et al., 2004). There are several potential sources enrichment can arise from. Examples are that resources (e.g., positive mood) gained in one role lead to better functioning in the other role (Sieber, 1974)[21] or skills and attitudes that are acquired in one role are useful in the other role (Crouter, 1984).[22]

Conceptually, enrichment between work and family is bi-directional. Most researchers make the distinction between what is termed work–family enrichment, and what is termed family–work enrichment. Work–family enrichment occurs, when ones involvement in work provides skills, behaviors, or positive mood which influences the family life in a positive way. Family-work enrichment, however, occurs when ones involvement in the family domain results in positive mood, feeling of success or support that help individuals to cope better with problems at work, feel more confident and in the end being more productive at work (Wayne, et al., 2004).

Several antecedents of work–family enrichment have been proposed. Personality traits, such as extraversion and openness for experience have been shown to be positively related to work–family enrichment (Wayne et al., 2004). Next to individual antecedents, organizational circumstances such as resources and skills gained at work foster the occurrence of work–family enrichment (Voydanoff, 2004).[23] For example, abilities such as interpersonal communication skills are learned at work and may then facilitate constructive communication with family members at home.

Work-life balance

The emergence of new family models

"Our review suggests that most of what is known about Work-Family issues is based on the experiences of heterosexual, Caucasian, managerial and professional employees in family arrangements" (Casper et al., 2007, p. 10).

The role of organization and supervisor

Research has focused especially on the role of the organization and the supervisor in the reduction of WFC. Results provide evidence for the negative association between the availability of family friendly resources provided by the work place and WFC. General support by the organization aids the employees to deal with work family issues so that organizational support is negatively connected to WFC (Kossek, Pichler, Bodner, & Hammer, 2011).[24] Furthermore, Kossek et al. (2011) showed that work family specific support has a stronger negative connection with work family conflict. Interesting results by other researchers show that family friendly organizational culture also has an indirect effect on WFC via supervisor support and coworker support (Dolcoy & Daley, 2009).[25] Surprisingly, some research also shows that the utilization of provided resources such as child care support or flexible work hours has no longitudinal connection with WFC (Hammer, Neal, Newson, Brockwood, & Colton, 2005).[26] This result speaks against common assumptions. Also, the supervisor has a social-support function for his/her subordinates. As Moen and Yu (2000)[27] showed supervisor support is an indicator for lower levels of WFC. Further support for this hypothesis stems from a study conducted by Thompson and Prottas (2005).[28] Keeping in mind the support function, organizations should provide trainings for the supervisors and conduct the selection process of new employees. Similar as for organizational support, the meta-analysis by Kossek et al. (2011) showed that general supervisor is negatively connected to WFC. Again, work–family-specific supervisor support has a stronger negative connection with WFC. Aside from support by the organization and the supervisor, research points out a third source of work-place support: The coworker. The informal support by the coworker not only correlates with positive aspects such as job satisfaction, but is also negatively associated with negative variables such as WFC (Dolcos & Doley, 2009; Thompson & Prottas, 2005).

In terms of work–family enrichment, supervisors and organizations are also relevant, since they are able to provide with important resource (e.g., skills and financial benefits) and positive affect.

Research methods to investigate

A methodological review by Casper, Eby, Bordeaux, Lockwood, and Lambert (2007)[29] summarizes the research methods used in the area of work-family research from 1980 to 2003. Their main findings are:

· The descriptions of sample characteristics are often inconsistent and leave out essential information necessary to evaluate if generalization is appropriate or not.

· Samples are mostly homogenous, neglecting diversity regarding racial, ethnic, cultural aspects, and non-traditional families (e.g., single or homosexual parents).

· The research design of most studies is cross-sectional and correlational. Field settings are predominant (97%). Only 2% use experimental designs.

· Surveys are mostly used for data collection (85%) whereas qualitative methods are used less often. Measures are mainly derived from one single person (76%) and focus on the individual level of analysis (89%). In this respect, research on, for example, dyads and groups have been neglected.

· Simple inferential statistics are preferred (79%) instead of, for example, structural equation modeling (17%).

· Regarding reliability aspects, coefficient alpha is often provided (87%), thereby reaching .79 on average. Pre-existing scales are often used (69%) containing multi-item measures (79%).

In light of these results, Casper, et al. (2007) give several recommendations. They suggest, for example, that researchers should use more longitudinal and experimental research designs, more diverse samples, data sources and levels of analysis.

References

- ↑ Greenhaus, J. H., & Allen, T. D. (2011). Work–family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (2nd ed.). (pp. 165–183). Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ Chan, Xi Wen; Field, Justin Craig (2018). "Contemporary Knowledge Workers and the Boundaryless Work–Life Interface: Implications for the Human Resource Management of the Knowledge Workforce" (in English). Frontiers in Psychology 9: 2414. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02414. ISSN 1664-1078. PMID 30555399.

- ↑ Chan, Xi Wen; Field, Justin Craig (2018). "Contemporary Knowledge Workers and the Boundaryless Work–Life Interface: Implications for the Human Resource Management of the Knowledge Workforce" (in English). Frontiers in Psychology 9: 2414. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02414. ISSN 1664-1078. PMID 30555399.

- ↑ Chan, Xi Wen; Field, Justin Craig (2018). "Contemporary Knowledge Workers and the Boundaryless Work–Life Interface: Implications for the Human Resource Management of the Knowledge Workforce" (in English). Frontiers in Psychology 9: 2414. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02414. ISSN 1664-1078. PMID 30555399.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Lavassani, K. M., & Movahedi, P. (2014). DEVELOPMENTS IN THEORIES AND MEASURES OF WORK-FAMILY. Contemporary Research on Organization Management and Administration, 2, 6–19.

- ↑ Lewis A. Coser: Greedy Institutions. Patterns of Undivided Commitment. The Free Press, New York 1974. Cited after: Jan Currie, Patricia Harris, Bev Thiele: Sacrifices in Greedy Universities: are they gendered? Gender and Education, 2000, Vol. 12, No. 3, p. 269–291. S. 270.

- ↑ Lewis A. Coser: Greedy Institutions. Patterns of Undivided Commitment. The Free Press, New York 1974. Cited after R. Burchielli, T. Bartram: Work-Family Balance or Greedy Organizations?, érudit, 2008, Vol. 63, No. 1, p. 108–133, doi:10.7202/018124ar

- ↑ Lewis A. Coser: Greedy Institutions. Patterns of Undivided Commitment. The Free Press, New York 1974. Cited after: Asher Cohen, Bernard Susser: Women Singing, Cadets Leaving. The Extreme Case Syndrome in Religion-Army Relationships, S. 127 ff. In: Elisheva Rosman-Stollman, Aharon Kampinsky: Civil–Military Relations in Israel: Essays in Honor of Stuart A. Cohen, Lexington Books, 2014, Script error: No such module "CS1 identifiers"., p. 130.

- ↑ Rosalind Edwards: Mature Women Students: Separating Or Connecting Family and Education, Taylor & Francis 1993, Script error: No such module "CS1 identifiers"., Chapter 4 'Greedy Institutions': Straddling the worlds of family and education. p. 62 ff.

- ↑ Jan Currie, Patricia Harris, Bev Thiele: Sacrifices in Greedy Universities: are they gendered? Gender and Education, 2000, Vol. 12, No. 3, p. 269–291.

- ↑ M.W. Segal: The Military And the Family As Greedy Institutions, Armed Forces & Society (1986), Vol. 13 No. 1, p. 9–38, doi:10.1177/0095327X8601300101 (abstract)

- ↑ Schultz Jennifer, Higbee Jeanne (April 2010). "An Exploration Of Theoretical Foundations For Working Mothers' Formal Workplace Social Networks". Journal of Business & Economics Research 8 (4): 87–94.

- ↑ Grandey, A. A., Cordeiro, B. L., & Crouter, A. C. (2005). A longitudinal and multi-source test of the work-family conflict and job satisfaction relationship. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 305–323.

- ↑ Lu, L., Kao, S. F., Cooper, C. L., Allen, T. D., Lapierre, L. M., O`Driscoll, M., Poelmans, S. A. Y., Sanchez, J. I., & Spector, P. L. (2009). Work resources, work-to-family conflict, and its consequences: A Taiwanese–British cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Stress Management, 16, 25-44.

- ↑ Pal, S., & Saksvik, P. Ø. (2008). Work–family conflict and psychosocial work environment stressors as predictors of job stress in a cross-cultural study. International Journal of Stress Management, 15, 22–42.

- ↑ Nielson, T. R., Carlson, D. S., & Lankau, M. J. (2001). The supportive mentor as a means of reducing Work–Family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59, 364–381.

- ↑ Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E., Anger, W., Bodner, T., & Zimmerman, K. L. (2011). Clarifying work–family intervention processes: The roles of work–family conflict and family-supportive supervisor behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 134–150.

- ↑ Wilson, M. G., Polzer-Debruyne, A., Chen, S. & Fernandes, S. (2007). Shift work interventions for reduced work–family conflict. Employee Relations, 29, 162–177.

- ↑ Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work–family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31, 72–92.

- ↑ Wayne, J. H., Musisca, N., & Fleeson, W. (2004). Considering the role of personality in the work–family experience: Relationships of the big five to work–family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64, 108–130. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00035-6

- ↑ Sieber, S. D. (1974). Toward a theory of role accumulation. American Sociological Review, 39, 567–578. doi:10.2307/2094422

- ↑ Crouter, A. C. (1984). Spillover from family to work: The neglected side of the work–family interface. Human Relations, 37, 425–441. doi:10.1177/001872678403700601

- ↑ Voydanoff, P. (2004). The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 398–412. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00028.x

- ↑ Kossek, E.E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T., & Hammer, L. (2011). Workplace Social Support and Work-Family Conflict: A Meta Analysis Clarifying the Influence of General and Work Specific Supervisor and Organizational Support. Personnel Psychology, 64, 289–313.

- ↑ Dolcos, S., & Daley, D. (2009). Work pressure, workplace social resources and work-family conflict: The tale of two sectors, International Journal of Stress Management, 16, 291–311.

- ↑ Hammer, L., Neal, M., Newson, J., Brockwood, K., & Colton, C. (2005). A Longitudinal Study of the Effects of Dual-Earner Couples’ Utilization of Family-Friendly Workplace Supports on Work and Family Outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 799–810.

- ↑ Moen, P., & Yu, Y. (2000). Effective work/life strategies: Working couples, work conditions, gender, and life quality. Social Problems, 47, 291–326.

- ↑ Thompson, C. A., & Prottas, D. F. (2005). Relationships among organizational family support, job autonomy, perceived control, and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 100–118.

- ↑ Casper, W. J., Eby, L. T., Bordeaux, C., Lockwood, A., & Lambert, D. (2007). A review of research methods in IO/OB work-family research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 28–43.

Work–life balance