Neural cryptography

Neural cryptography is a branch of cryptography dedicated to analyzing the application of stochastic algorithms, especially artificial neural network algorithms, for use in encryption and cryptanalysis.

Definition

Artificial neural networks are well known for their ability to selectively explore the solution space of a given problem. This feature finds a natural niche of application in the field of cryptanalysis. At the same time, neural networks offer a new approach to attack ciphering algorithms based on the principle that any function could be reproduced by a neural network, which is a powerful proven computational tool that can be used to find the inverse-function of any cryptographic algorithm.

The ideas of mutual learning, self learning, and stochastic behavior of neural networks and similar algorithms can be used for different aspects of cryptography, like public-key cryptography, solving the key distribution problem using neural network mutual synchronization, hashing or generation of pseudo-random numbers.

Another idea is the ability of a neural network to separate space in non-linear pieces using "bias". It gives different probabilities of activating the neural network or not. This is very useful in the case of Cryptanalysis.

Two names are used to design the same domain of research: Neuro-Cryptography and Neural Cryptography.

The first work that it is known on this topic can be traced back to 1995 in an IT Master Thesis.

Applications

In 1995, Sebastien Dourlens applied neural networks to cryptanalyze DES by allowing the networks to learn how to invert the S-tables of the DES. The bias in DES studied through Differential Cryptanalysis by Adi Shamir is highlighted. The experiment shows about 50% of the key bits can be found, allowing the complete key to be found in a short time. Hardware application with multi micro-controllers have been proposed due to the easy implementation of multilayer neural networks in hardware.

One example of a public-key protocol is given by Khalil Shihab. He describes the decryption scheme and the public key creation that are based on a backpropagation neural network. The encryption scheme and the private key creation process are based on Boolean algebra. This technique has the advantage of small time and memory complexities. A disadvantage is the property of backpropagation algorithms: because of huge training sets, the learning phase of a neural network is very long. Therefore, the use of this protocol is only theoretical so far.

Neural key exchange protocol

The most used protocol for key exchange between two parties A and B in the practice is Diffie–Hellman key exchange protocol. Neural key exchange, which is based on the synchronization of two tree parity machines, should be a secure replacement for this method. Synchronizing these two machines is similar to synchronizing two chaotic oscillators in chaos communications.

Tree parity machine

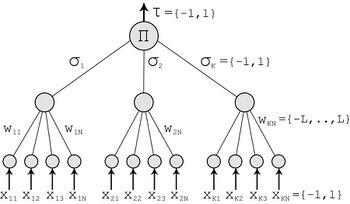

The tree parity machine is a special type of multi-layer feedforward neural network.

It consists of one output neuron, K hidden neurons and K×N input neurons. Inputs to the network take three values:

The weights between input and hidden neurons take the values:

Output value of each hidden neuron is calculated as a sum of all multiplications of input neurons and these weights:

Signum is a simple function, which returns −1,0 or 1:

If the scalar product is 0, the output of the hidden neuron is mapped to −1 in order to ensure a binary output value. The output of neural network is then computed as the multiplication of all values produced by hidden elements:

Output of the tree parity machine is binary.

Protocol

Each party (A and B) uses its own tree parity machine. Synchronization of the tree parity machines is achieved in these steps

- Initialize random weight values

- Execute these steps until the full synchronization is achieved

- Generate random input vector X

- Compute the values of the hidden neurons

- Compute the value of the output neuron

- Compare the values of both tree parity machines

- Outputs are the same: one of the suitable learning rules is applied to the weights

- Outputs are different: go to 2.1

After the full synchronization is achieved (the weights wij of both tree parity machines are same), A and B can use their weights as keys.

This method is known as a bidirectional learning.

One of the following learning rules[1] can be used for the synchronization:

- Hebbian learning rule:

- Anti-Hebbian learning rule:

- Random walk:

Where:

- if otherwise

And:

- is a function that keeps the in the range

Attacks and security of this protocol

In every attack it is considered, that the attacker E can eavesdrop messages between the parties A and B, but does not have an opportunity to change them.

Brute force

To provide a brute force attack, an attacker has to test all possible keys (all possible values of weights wij). By K hidden neurons, K×N input neurons and boundary of weights L, this gives (2L+1)KN possibilities. For example, the configuration K = 3, L = 3 and N = 100 gives us 3*10253 key possibilities, making the attack impossible with today's computer power.

Learning with own tree parity machine

One of the basic attacks can be provided by an attacker, who owns the same tree parity machine as the parties A and B. He wants to synchronize his tree parity machine with these two parties. In each step there are three situations possible:

- Output(A) ≠ Output(B): None of the parties updates its weights.

- Output(A) = Output(B) = Output(E): All the three parties update weights in their tree parity machines.

- Output(A) = Output(B) ≠ Output(E): Parties A and B update their tree parity machines, but the attacker can not do that. Because of this situation his learning is slower than the synchronization of parties A and B.

It has been proven, that the synchronization of two parties is faster than learning of an attacker. It can be improved by increasing of the synaptic depth L of the neural network. That gives this protocol enough security and an attacker can find out the key only with small probability.

Other attacks

For conventional cryptographic systems, we can improve the security of the protocol by increasing of the key length. In the case of neural cryptography, we improve it by increasing of the synaptic depth L of the neural networks. Changing this parameter increases the cost of a successful attack exponentially, while the effort for the users grows polynomially. Therefore, breaking the security of neural key exchange belongs to the complexity class NP.

Alexander Klimov, Anton Mityaguine, and Adi Shamir say that the original neural synchronization scheme can be broken by at least three different attacks—geometric, probabilistic analysis, and using genetic algorithms. Even though this particular implementation is insecure, the ideas behind chaotic synchronization could potentially lead to a secure implementation.[2]

Permutation parity machine

The permutation parity machine is a binary variant of the tree parity machine.[3]

It consists of one input layer, one hidden layer and one output layer. The number of neurons in the output layer depends on the number of hidden units K. Each hidden neuron has N binary input neurons:

The weights between input and hidden neurons are also binary:

Output value of each hidden neuron is calculated as a sum of all exclusive disjunctions (exclusive or) of input neurons and these weights:

(⊕ means XOR).

The function is a threshold function, which returns 0 or 1:

The output of neural network with two or more hidden neurons can be computed as the exclusive or of the values produced by hidden elements:

Other configurations of the output layer for K>2 are also possible.[3]

This machine has proven to be robust enough against some attacks[4] so it could be used as a cryptographic mean, but it has been shown to be vulnerable to a probabilistic attack.[5]

Security against quantum computers

A quantum computer is a device that uses quantum mechanisms for computation. In this device the data are stored as qubits (quantum binary digits). That gives a quantum computer in comparison with a conventional computer the opportunity to solve complicated problems in a short time, e.g. discrete logarithm problem or factorization. Algorithms that are not based on any of these number theory problems are being searched because of this property.

Neural key exchange protocol is not based on any number theory. It is based on the difference between unidirectional and bidirectional synchronization of neural networks. Therefore, something like the neural key exchange protocol could give rise to potentially faster key exchange schemes.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ Singh, Ajit; Nandal, Aarti (May 2013). "Neural Cryptography for Secret Key Exchange and Encryption with AES". International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science and Software Engineering 3 (5): 376–381. ISSN 2277-128X. http://ijarcsse.com/Before_August_2017/docs/papers/Volume_3/5_May2013/V3I5-0187.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Klimov, Alexander; Mityagin, Anton; Shamir, Adi (2002). "Analysis of Neural Cryptography". ASIACRYPT 2002. 2501. pp. 288–298. doi:10.1007/3-540-36178-2_18. https://iacr.org/archive/asiacrypt2002/25010286/25010286.pdf. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Reyes, O. M.; Kopitzke, I.; Zimmermann, K.-H. (April 2009). "Permutation Parity Machines for Neural Synchronization". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 42 (19): 195002. doi:10.1088/1751-8113/42/19/195002. ISSN 1751-8113. Bibcode: 2009JPhA...42s5002R.

- ↑ Reyes, Oscar Mauricio; Zimmermann, Karl-Heinz (June 2010). "Permutation parity machines for neural cryptography". Physical Review E 81 (6): 066117. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.81.066117. ISSN 1539-3755. PMID 20866488. Bibcode: 2010PhRvE..81f6117R.

- ↑ Seoane, Luís F.; Ruttor, Andreas (February 2012). "Successful attack on permutation-parity-machine-based neural cryptography". Physical Review E 85 (2): 025101. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.85.025101. ISSN 1539-3755. PMID 22463268. Bibcode: 2012PhRvE..85b5101S.

- Neuro-Cryptography 1995 - The first definition of the Neuro-Cryptography (AI Neural-Cryptography) applied to DES cryptanalysis by Sebastien Dourlens, France.

- Neural Cryptography - Description of one kind of neural cryptography at the University of Würzburg, Germany.

- Kinzel, W.; Kanter, I. (2002). "Neural cryptography". ICONIP '02. pp. 1351–1354. doi:10.1109/ICONIP.2002.1202841. - One of the leading papers that introduce the concept of using synchronized neural networks to achieve a public key authentication system.

- Li, Li-Hua; Lin, Luon-Chang; Hwang, Min-Shiang (November 2001). "A remote password authentication scheme for multiserver architecture using neural networks". IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 12 (6): 1498–1504. doi:10.1109/72.963786. ISSN 1045-9227. PMID 18249979. - Possible practical application of Neural Cryptography.

- Klimov, Alexander; Mityagin, Anton; Shamir, Adi (2002). "Analysis of Neural Cryptography". ASIACRYPT 2002. 2501. pp. 288–298. doi:10.1007/3-540-36178-2_18. https://iacr.org/archive/asiacrypt2002/25010286/25010286.pdf. Retrieved 2017-11-15. - Analysis of neural cryptography in general and focusing on the weakness and possible attacks of using synchronized neural networks.

- Neural Synchronization and Cryptography - Andreas Ruttor. PhD thesis, Bayerische Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg, 2006.

- Ruttor, Andreas; Kinzel, Wolfgang; Naeh, Rivka; Kanter, Ido (March 2006). "Genetic attack on neural cryptography". Physical Review E 73 (3): 036121. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.73.036121. ISSN 1539-3755. PMID 16605612. Bibcode: 2006PhRvE..73c6121R.

- Khalil Shihab (2006). "A backpropagation neural network for computer network security". Journal of Computer Science 2: 710–715. Archived from the original on 2007-07-12. https://web.archive.org/web/20070712012959/http://www.scipub.org/fulltext/jcs/jcs29710-715.pdf.

|