Parabolic cylindrical coordinates

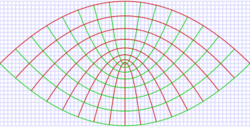

In mathematics, parabolic cylindrical coordinates are a three-dimensional orthogonal coordinate system that results from projecting the two-dimensional parabolic coordinate system in the perpendicular -direction. Hence, the coordinate surfaces are confocal parabolic cylinders. Parabolic cylindrical coordinates have found many applications, e.g., the potential theory of edges.

Basic definition

The parabolic cylindrical coordinates (σ, τ, z) are defined in terms of the Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z) by:

The surfaces of constant σ form confocal parabolic cylinders

that open towards +y, whereas the surfaces of constant τ form confocal parabolic cylinders

that open in the opposite direction, i.e., towards −y. The foci of all these parabolic cylinders are located along the line defined by x = y = 0. The radius r has a simple formula as well

that proves useful in solving the Hamilton–Jacobi equation in parabolic coordinates for the inverse-square central force problem of mechanics; for further details, see the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector article.

Scale factors

The scale factors for the parabolic cylindrical coordinates σ and τ are:

Differential elements

The infinitesimal element of volume is

The differential displacement is given by:

The differential normal area is given by:

Del

Let f be a scalar field. The gradient is given by

The Laplacian is given by

Let A be a vector field of the form:

The divergence is given by

The curl is given by

Other differential operators can be expressed in the coordinates (σ, τ) by substituting the scale factors into the general formulae found in orthogonal coordinates.

Relationship to other coordinate systems

Relationship to cylindrical coordinates (ρ, φ, z):

Parabolic unit vectors expressed in terms of Cartesian unit vectors:

Parabolic cylinder harmonics

Since all of the surfaces of constant σ, τ and z are conicoids, Laplace's equation is separable in parabolic cylindrical coordinates. Using the technique of the separation of variables, a separated solution to Laplace's equation may be written:

and Laplace's equation, divided by V, is written:

Since the Z equation is separate from the rest, we may write

where m is constant. Z(z) has the solution:

Substituting −m2 for , Laplace's equation may now be written:

We may now separate the S and T functions and introduce another constant n2 to obtain:

The solutions to these equations are the parabolic cylinder functions

The parabolic cylinder harmonics for (m, n) are now the product of the solutions. The combination will reduce the number of constants and the general solution to Laplace's equation may be written:

Applications

The classic applications of parabolic cylindrical coordinates are in solving partial differential equations, e.g., Laplace's equation or the Helmholtz equation, for which such coordinates allow a separation of variables. A typical example would be the electric field surrounding a flat semi-infinite conducting plate.

See also

Bibliography

- Morse PM, Feshbach H (1953). Methods of Theoretical Physics, Part I. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 658. ISBN 0-07-043316-X.

- Margenau H, Murphy GM (1956). The Mathematics of Physics and Chemistry. New York: D. van Nostrand. pp. 186–187. https://archive.org/details/mathematicsofphy0002marg.

- Korn GA, Korn TM (1961). Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 181. ASIN B0000CKZX7.

- Sauer R, Szabó I (1967). Mathematische Hilfsmittel des Ingenieurs. New York: Springer Verlag. p. 96.

- Zwillinger D (1992). Handbook of Integration. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett. p. 114. ISBN 0-86720-293-9. Same as Morse & Feshbach (1953), substituting uk for ξk.

- Moon P, Spencer DE (1988). "Parabolic-Cylinder Coordinates (μ, ν, z)". Field Theory Handbook, Including Coordinate Systems, Differential Equations, and Their Solutions (corrected 2nd ed., 3rd print ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 21–24 (Table 1.04). ISBN 978-0-387-18430-2.

External links

|