Paraboloidal coordinates

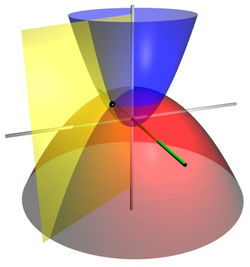

Paraboloidal coordinates are three-dimensional orthogonal coordinates that generalize two-dimensional parabolic coordinates. They possess elliptic paraboloids as one-coordinate surfaces. As such, they should be distinguished from parabolic cylindrical coordinates and parabolic rotational coordinates, both of which are also generalizations of two-dimensional parabolic coordinates. The coordinate surfaces of the former are parabolic cylinders, and the coordinate surfaces of the latter are circular paraboloids.

Differently from cylindrical and rotational parabolic coordinates, but similarly to the related ellipsoidal coordinates, the coordinate surfaces of the paraboloidal coordinate system are not produced by rotating or projecting any two-dimensional orthogonal coordinate system.

Basic formulas

The Cartesian coordinates can be produced from the ellipsoidal coordinates by the equations[1]

with

Consequently, surfaces of constant are downward opening elliptic paraboloids:

Similarly, surfaces of constant are upward opening elliptic paraboloids,

whereas surfaces of constant are hyperbolic paraboloids:

Scale factors

The scale factors for the paraboloidal coordinates are[2]

Hence, the infinitesimal volume element is

Differential operators

Common differential operators can be expressed in the coordinates by substituting the scale factors into the general formulas for these operators, which are applicable to any three-dimensional orthogonal coordinates. For instance, the gradient operator is

and the Laplacian is

Applications

Paraboloidal coordinates can be useful for solving certain partial differential equations. For instance, the Laplace equation and Helmholtz equation are both separable in paraboloidal coordinates. Hence, the coordinates can be used to solve these equations in geometries with paraboloidal symmetry, i.e. with boundary conditions specified on sections of paraboloids.

The Helmholtz equation is . Taking , the separated equations are[3]

where and are the two separation constants. Similarly, the separated equations for the Laplace equation can be obtained by setting in the above.

Each of the separated equations can be cast in the form of the Baer equation. Direct solution of the equations is difficult, however, in part because the separation constants and appear simultaneously in all three equations.

Following the above approach, paraboloidal coordinates have been used to solve for the electric field surrounding a conducting paraboloid.[4]

References

- ↑ Yoon, LCLY; M, Willatzen (2011), Separable Boundary-Value Problems in Physics, Wiley-VCH, p. 217, ISBN 978-3-527-63492-7

- ↑ Willatzen and Yoon (2011), p. 219

- ↑ Willatzen and Yoon (2011), p. 227

- ↑ Duggen, L; Willatzen, M; Voon, L C Lew Yan (2012), "Laplace boundary-value problem in paraboloidal coordinates", European Journal of Physics 33 (3): 689–696, doi:10.1088/0143-0807/33/3/689, Bibcode: 2012EJPh...33..689D

Bibliography

- Separable Boundary-Value Problems in Physics. Wiley-VCH. 2011. ISBN 978-3-527-41020-0.

- Methods of Theoretical Physics, Part I. New York: McGraw-Hill. 1953. p. 664. ISBN 0-07-043316-X.

- The Mathematics of Physics and Chemistry. New York: D. van Nostrand. 1956. pp. 184–185. https://archive.org/details/mathematicsofphy0002marg.

- Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers. New York: McGraw-Hill. 1961. p. 180. ASIN B0000CKZX7. https://archive.org/details/mathematicalhand0000korn.

- Arfken G (1970). Mathematical Methods for Physicists (2nd ed.). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. pp. 119–120.

- Mathematische Hilfsmittel des Ingenieurs. New York: Springer Verlag. 1967. p. 98.

- Zwillinger D (1992). Handbook of Integration. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett. p. 114. ISBN 0-86720-293-9. Same as Morse & Feshbach (1953), substituting uk for ξk.

- "Paraboloidal Coordinates (μ, ν, λ)". Field Theory Handbook, Including Coordinate Systems, Differential Equations, and Their Solutions (corrected 2nd ed., 3rd print ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. 1988. pp. 44–48 (Table 1.11). ISBN 978-0-387-18430-2.

External links

|