Philosophy:Female intrasexual competition

Female intrasexual competition is competition between women over a potential mate. Such competition might include self-promotion, derogation of other women, and direct and indirect aggression toward other women. Factors that influence female intrasexual competition include the genetic quality of available mates, hormone levels, and interpersonal dynamics.

There are two modes of sexual selection: intersexual selection and intrasexual selection. Intersexual selection includes the display of desirable sexual characteristics to attract a potential mate. Intrasexual selection is competition between members of the same sex other over a potential mate.

Compared to males, females tend to prefer subtle rather than overt forms of intrasexual competition.[1][2] However, they are also less likely to resolve a conflict with a same sex peer.[3]

Self-promotion tactics

Self-promotion tactics are one of the main strategies that can be used during intrasexual competition for mates.[4] It is often perceived to be the most socially desirable strategy, as it can be perceived as self-improvement, rather than an attack on competitors. Self-promotion tactics are especially useful for when women are looking for short-term mates, as such tactics will directly promote their sexual availability.[5]

Luxury consumption

Self-promotion tactics refers to the different strategies that women might use to make themselves look better compared to other competing women. For example, women are interested in luxury items that enhance their attractiveness.[6] Luxury items can indicate attractiveness by emphasising a higher status, which is a factor that potential mates will take into consideration. When testing for female intrasexual competition, research has shown that women would purposely choose luxury items that boosts their level of attractiveness, and will disregard non-attractive items, even if they are luxury items. When consuming attractive luxury items, women are perceived to be more attractive, young, and flirty by other women. At the same time, such consumption portrays their willingness to engage in sexual activity.[citation needed]

When women's hormonal cycles are nearing the ovulation stage, which is peak fertility, they have a higher tendency to choose products that would enhance their attractiveness, such as sexier and more revealing clothes.[citation needed] It has been shown that when women are at their peak fertility, they will have an increased awareness and sensitivity to female intrasexual competition. This is due to the fact that when women are at their peak fertility, this is the most optimal time for them to mate and produce offspring.[7] However, this tends to be only applied in situations when women are faced with rivals who they consider to be attractive. When with an unattractive rival, women might not necessarily see them posing any threat, as they would feel more attractive in comparison.[8]

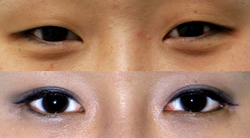

Cosmetic surgery

By using plastic surgery, women can surgically change their appearances to make themselves more attractive. They can surgically alter their faces and bodies according to their wishes. They can use botulinum toxin to prevent wrinkles and get face lifts. Or they can use get liposuction to remove fat and achieve a more desirable body. Research has shown that the waist–hip ratio (WHR) of a female is a good indicator of their health, and that males tend to have a preference for females with a low WHR.[9] When comparing women's pre- and post-operative photographs, post-operative photographs where women have a lower WHR are rated as more attractive, regardless of their weight gain or their body mass index (BMI).[10] Culture plays a role in the type of plastic surgery a woman gets. The beauty standards for Westerners and Easterners are extremely different. Western models tend to be used to promote clothing and to portray seductiveness, whereas Asian models tend to be used to promote hair and skin products. Research suggest that Western models are more body-oriented.[11][12]

Regardless, by using cosmetic surgery, females can change various aspects of their body to make themselves more attractive by displaying a more desirable waist–hip ratio. This can lead to competition with other females who may be considered less attractive in comparison. When women change their appearances, such as by applying cosmetic products and wearing sexy or stylish clothes, do make a difference and has been proven to be effective.[4]

Clothing and make-up

Use of certain clothing strategically can increase women's appeal, most commonly such as emphasizing the décolletage, wearing body-hugging outfits, and choosing leg-revealing attire and other garmets that accentuate specific body parts.

Women often opt for clothing with plunging necklines or low-cut tops, a style which draws attention to the cleavage, thus accentuating the area. This leverages the emphasis on sexually dimorphic traits and can enhance a woman's appeal. And reversely crop-tops, which would expose the midriff area or waistline.

Wearing form-fitting attire, such as dresses that highlight the waist and hips or pants that accentuate curves, is a common strategy to enhance the overall figure. Such outfits highlight the importance of the waist-hip ratio (WHR).[13]

Short skirts, high-heels, and attire that showcases the legs. These clothing choices subtly emphasize leg length and overall body proportions, which are characteristics often deemed attractive.

Makeup, too, plays a role in self-promotion, allowing to enhance certain facial features and draw attention to specific areas such as the eyes and lips.[14]

Competitor derogation

There are a number of competitive strategies that females may use in a bid to appear more attractive in comparison to other females. Whilst males may use direct forms of aggression during intrasexual competition[15][16] females typically compete for access to desired mates through the use of indirect aggression. Unlike direct aggression which involves delivering harm face to face,[17] indirect aggression describes acts that are done circuitously, where an individual aims to cause harm but attempts to appear as if they have no harmful intentions.[18] In the context of intrasexual competition, indirect aggression works to reduce the opportunities the rival may have in securing access to the desired mate to, therefore, increase one's chances of reproductive success.[19] These include behaviours such as shunning, social exclusion, getting others to dislike the individual, spreading rumours and criticizing the rival's appearance.

Female derogation

Female derogation is a form of indirect aggression where females attempt to reduce the perceived value of another female 'rival'. Fisher (2004)[20] studied female derogation and the effects of estrogen levels on this form of competition. Females disclosed their ovulation status and rated the attractiveness of male and female faces. Competitor derogation (giving low ratings) towards same-sex rivals occurred frequently when women were at their most fertile stages. In contrast, women gave same-sex rivals higher ratings during the least fertile stages of their ovulation. This indirect form of competition appears exclusive toward females as findings also showed that women, irrespective of ovulation status (high or low), showed no difference in the rating of male faces. Supporting research has also found that younger women who are considered as having high fertility, gossip about other women more than older women, who are no longer at their most fertile stage.[21]

Indeed, indirect aggression appears more prevalent amongst (or exclusive to) females than males who are said to engage in more direct forms of competition.[22] Research studying the relationship between indicators of attractiveness, such as physical attractiveness and indirect victimisation, showed that the likelihood of experiencing indirect victimization increased by 35% for females who perceived themselves as physically attractive.[23] In contrast, being a male who is physically attractive decreased the chances of experiencing such indirect victimization. This also highlights how the physical attractiveness of a female is a trigger for indirect aggression and forms a core part of intersexual selection between the sexes.

Female derogation is also used to enforce equality amongst females which prevents high-status ambitious females from using their status to gain resources, allies and mates at the expense of other females. Thus attempts to gain social status are punished while norms of "niceness" (which is defined as a lack of competitiveness) and equality dominates as a social norm amongst females. Equality is enforced by threat of social exclusion (which can be directed against any female but females attempting to gain status are more likely to be targets) and low thresholds for dissolving relationships when inequality arises. Within a peer group, a high-status girl who tries to interfere with another's goals risks social derision and exclusion.[2]

Slut-shaming

Another form of competitor derogation that is instrumental in making rivals appear less desirable is slut-shaming. In slut-shaming, females criticize and derogate same-sex rivals for engaging in sexual behaviors that are deemed "unacceptable" by society's standards, as it violates social expectations and norms with regards to their gender role. For example, an act of sexual promiscuity demonstrated by a female is often considered non-conventional and inappropriate as such behaviors are not viewed as acts that constitute femininity. Females may choose to personally confront or spread rumors and gossip about the promiscuous activity of another female. Buss and Dedden explored sex differences in competitor derogation to investigate the tactics that are commonly adopted by both sexes for intrasexual competition.[24] Researchers presented both sexes with a list of tactics that are often employed by individuals to derogate same-sex competitors in an attempt to make them look undesirable to the opposite sex. On a scale from 1 (likely) to 7 (unlikely), participants rated the likelihood that members of their own sex would perform each act. Results revealed that tactics that pointed out a competitor's promiscuity were used by females more frequently than males. These involved "calling her a tramp", "telling everyone that she sleeps around a lot" and that "she cheats on men". Indeed, accusations of promiscuity are a frequent cause of female-female violence, where females may physically retaliate in a bid to defend their sexual reputation.[25] British schoolgirls were surveyed and asked questions about their involvement in fights. In addition to 89% stating that they had actually been involved in a fight, 46% of reported fights were attacks on personal integrity related to promiscuity or gossiping.[26]

With an ultimate goal of enhancing reproductive success at the expense of others, slut-shaming effectively works to arouse suspicion and cause suitors to question the fidelity of these females. In the long term, men may have doubts regarding the paternity of any offspring produced and since humans strive for reproductive success, (which, for a man is to reproduce and to continually invest in his own children), the decision to mate with such an individual drastically reduces the chances of reproductive success. Considering this and the high-value that men attach to women who practice chastity, men are less likely to mate with a supposedly promiscuous female due to the fear of becoming a cuckold.

The effectiveness of strategies: competitor derogation vs. self-promotion tactics

Generally speaking, competitor derogation is often rated as less effective than self-promotion tactics. Men and women tend to judge self-promotion tactics that show resource potential and sexual availability as highly effective for short and long-term mating, respectively.[27] Women, relative to men, appear more likely to engage in self-promotion than competitor derogation tactics.[28] With females having a tendency to engage in more indirect forms of aggression/derogation such as spreading rumors and shunning (social manipulation),[18][19] studies investigate the extent to which such strategies enable females success by increasing their mating opportunities. Common indicators of reproductive success are sexual activity and dating behaviors. Research has found that the use of indirect aggression is positively correlated with increased dating behavior and early engagement in sexual activity. Arnocky and Pavilion[29] investigated whether the use of victimization or personally experiencing victimization could predict the dating behavior of adolescents over a year. In a follow-up assessment, indirect aggression (peer-nominated) was found to predict dating behavior one year after the initial assessment. Moreover, indirect aggression appeared to be a more powerful predictor of dating behavior than other factors such as initial dating status, peer-rated attractiveness, peer-perceived popularity, and age. Overall, females who used indirect aggression were more likely to be dating in comparison to victimized individuals, who were less likely to have a dating partner. The notion that peer aggression is associated with adaptive dating outcomes is further supported by studies that note that females who frequently displayed indirect aggression began dating much earlier in life than individuals who experienced female-female peer victimization, for whom dating behavior had a much later onset.[30] Dating popularity is also found to have a strong association with the use of indirect aggression.[31] With regards to sexual activity, White et al.[32] investigated the influence of peer victimization and perpetuated aggression on reproductive opportunities amongst young adults. Measures of sexual activity such as the number of previous sexual partners and the age of their first sexual intercourse were obtained alongside measures of their social experiences in middle and high school. Results found that females who experienced more peer aggression during adolescence had their first sexual intercourse at a later age. In contrast, females who perpetuated high levels of indirect peer aggression tended to have their first sexual encounter at earlier stages of adolescence.

Overall, indirect aggression (peer aggression) appears functional in maximizing one's own reproductive opportunities at the expense of same-sex rivals. A quote by Tracy Vaillancourt neatly concludes the literature on female-female aggression by stating: "Not only does such cattiness make the targeted women too sad and anxious to compete in the sexual market, some studies suggest it can make men find rivals less attractive".

Variables that influence female competition

Females often compete using low-risk strategies compared to males as females have to provide primary care and protection to their offspring.[33] Fisher (2015) suggested that attractiveness is the single route by which women compete and men have shown a preference for attractive women. [34]

Other factors that influence women's intrasexual competition are:

High genetic quality of the males

Females will promote themselves more often when males demonstrate various abilities to provide secure resources, protection for offspring, or when the costs of competing are inferior to the benefits gained.[35] They choose males with the highest possible qualities that can maximise reproductive success. Attractiveness and gene quality are both believed to be highly correlated.[36][37] Some research suggests that male attractiveness is biased by female's phenotypic quality, male attractiveness does not necessarily correspond to their gene quality.[38] This leads to the state-dependent choice theory which suggests females with lower qualities prefer low-quality males than high-quality males.[39][40][41] Promiscuity does not affect attractiveness rankings if physical attractiveness outweighs this variable.[42]

Ovarian hormones and hormonal variations

The ovarian cycle phase is an emerging concern in exploring issues related to female intrasexual competitive behaviour. It has been found that when fertility rate was maximised during the ovarian phase, women gave significantly lower ratings of attractiveness to other females. Ovarian hormones affect how females view their potential competitors and cause them to behave more competitively.[20][43]

Many studies implied that testosterone levels were one of the key factors in aggressive competitive behaviour in social situations.[44][45] When testosterone is produced in the brain and gonads in both genders, the androgen receptors in neural and peripheral tissues are being possessed and trigger behavioural and physiological responses to testosterone. The role of androgenic steroids is to activate or facilitate aggressive behaviour.[46] High levels of oestrogen are shown to have an effect on women's derogation on potential competitors (e.g. rating other female faces as less attractive) but there is no effect on ratings of male attractiveness.[20]

Interpersonal dynamics

Females often compete with their own sex to gain the attention of potential mates with high genetic qualities in order to induce reproductive success.[47][48] Miller et al. (2011)’s study revealed that presence of another sex individual leads to testosterone enhancement.[49]

The ratio of females to males in the course of competition might alter salivary testosterone levels in both genders which lead to competition.[47] The nonequivalent ratio of men with "good genes" to a large number of accessible females also leads to female intrasexual competition. Biosocial status hypothesis[47] indicated that to win in the female competition, it is thought to enhance in testosterone production thus facilitating violent, prevailing behaviours and exhibition of high status. Whereas, losing in female competition lowers testosterone levels which weaken the tendency of competing.[50][51] Testosterone levels correspond to various factors such as form of competition,[44] characteristics of opponent,[52] psychological state and baseline hormone levels of the person competing.

See also

- Dominance hierarchy

- Sexual selection

- Queen Bees and Wannabes

References

- ↑ Benenson, Joyce F.; Abadzi, Helen (2020). "Contest versus scramble competition: Sex differences in the quest for status". Current Opinion in Psychology 33: 62–68. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.013. PMID 31400660.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Benenson, Joyce F. (2013). "The development of human female competition: allies and adversaries". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 368 (1631): 20130079. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0079. PMID 24167309.

- ↑ Benenson, Joyce F.; Kuhn, Melissa N.; Ryan, Patrick J. et al. (2014). "Human males appear more prepared than females to resolve conflicts with same-sex peers". Human Nature 25 (2): 251–268. doi:10.1007/s12110-014-9198-z. PMID 24845881.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Fisher, Maryanne; Cox, Anthony (2011-03-01). "Four strategies used during intrasexual competition for mates" (in en). Personal Relationships 18 (1): 20–38. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01307.x. ISSN 1475-6811.

- ↑ Schmitt, D. P.; Buss, D. M. (1996-06-01). "Strategic self-promotion and competitor derogation: sex and context effects on the perceived effectiveness of mate attraction tactics". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70 (6): 1185–1204. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1185. ISSN 0022-3514. PMID 8667162.

- ↑ Hudders, L.; Backer, C. De; Fisher, M.; Vyncke, P. (2014-07-01). "The Rival Wears Prada: Luxury Consumption as a Female Competition Strategy". Evolutionary Psychology 12 (3): 570–587. doi:10.1177/147470491401200306. ISSN 1474-7049. PMID 25299993. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261145378.

- ↑ Durante, Kristina M.; Griskevicius, Vladas; Hill, Sarah E.; Perilloux, Carin; Li, Norman P. (2011-04-01). "Ovulation, Female Competition, and Product Choice: Hormonal Influences on Consumer Behavior" (in en). Journal of Consumer Research 37 (6): 921–934. doi:10.1086/656575. ISSN 0093-5301.

- ↑ Haselton, Martie G.; Mortezaie, Mina; Pillsworth, Elizabeth G.; Bleske-Rechek, April; Frederick, David A. (2007-01-01). "Ovulatory shifts in human female ornamentation: Near ovulation, women dress to impress". Hormones and Behavior 51 (1): 40–45. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.07.007. PMID 17045994.

- ↑ Singh, Devendra; Singh, Dorian (2011-02-06). "Shape and Significance of Feminine Beauty: An Evolutionary Perspective" (in en). Sex Roles 64 (9–10): 723–731. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9938-z. ISSN 0360-0025.

- ↑ Singh, Devendra; Randall, Patrick K. (2007-07-01). "Beauty is in the eye of the plastic surgeon: Waist–hip ratio (WHR) and women's attractiveness". Personality and Individual Differences 43 (2): 329–340. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.12.003.

- ↑ Frith, Katherine Toland; Cheng, Hong; Shaw, Ping (2004-01-01). "Race and Beauty: A Comparison of Asian and Western Models in Women's Magazine Advertisements" (in en). Sex Roles 50 (1–2): 53–61. doi:10.1023/B:SERS.0000011072.84489.e2. ISSN 0360-0025.

- ↑ Frith, Katherine; Shaw, Ping; Cheng, Hong (2005-03-01). "The Construction of Beauty: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Women's Magazine Advertising" (in en). Journal of Communication 55 (1): 56–70. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb02658.x. ISSN 1460-2466.

- ↑ Kościński, Krzysztof (July 2014). "Assessment of Waist-to-Hip Ratio Attractiveness in Women: An Anthropometric Analysis of Digital Silhouettes" (in en). Archives of Sexual Behavior 43 (5): 989–997. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0166-1. ISSN 0004-0002. PMID 23975738.

- ↑ Hendrie, Colin; Chapman, Rhiannon; Gill, Charlotte (2020-01-01). "Women's strategic use of clothing and make-up". Human Ethology 35 (1): 16–26. doi:10.22330/he/35/016-026. http://ishe.org/volume-35-2020/womens-strategic-use-of-clothing-and-make-up/.

- ↑ Shackelford, Todd (2012). The Oxford handbook of evolutionary perspectives on violence, homicide, and war. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199738403.

- ↑ Benenson, Joyce F. (2009-08-01). "Dominating versus eliminating the competition: Sex differences in human intrasexual aggression". Behavioral and Brain Sciences 32 (3–4): 268–269. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999046X. ISSN 1469-1825.

- ↑ Richardson, Deborah R.; Green, Laura R. (1999-01-01). "Social sanction and threat explanations of gender effects on direct and indirect aggression" (in en). Aggressive Behavior 25 (6): 425–434. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-2337(1999)25:6<425::aid-ab3>3.3.co;2-n. ISSN 1098-2337.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Bjorkqvist, Kaj; Österman, Karin; Lagerspetz, Kirsti (June 1, 1994). "Sex differences in covert aggression among adults". Aggressive Behavior 20 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1994)20:1<27::AID-AB2480200105>3.0.CO;2-Q.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Vaillancourt, Tracy (2013-12-05). "Do human females use indirect aggression as an intrasexual competition strategy?" (in en). Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 368 (1631): 20130080. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0080. ISSN 0962-8436. PMID 24167310.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Fisher, M. L. (2004). "Female intrasexual competition decreases female facial attractiveness". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 271 (Suppl_5): S283–S285. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0160. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 15503995.

- ↑ Massar, Karlijn; Buunk, Abraham P.; Rempt, Sanna (2012-01-01). "Age differences in women's tendency to gossip are mediated by their mate value". Personality and Individual Differences 52 (1): 106–109. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.09.013. https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/portal/en/publications/age-differences-in-womens-tendency-to-gossip-are-mediated-by-their-mate-value(413819a2-6142-45f3-8198-372b4be24b7b).html.

- ↑ Campbell, A (2004). "Female competition: Causes, constraints, content, and contexts". Journal of Sex Research 41 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1080/00224490409552210. PMID 15216421.

- ↑ Leenaars, Lindsey S.; Dane, Andrew V.; Marini, Zopito A. (2008-07-01). "Evolutionary perspective on indirect victimization in adolescence: the role of attractiveness, dating and sexual behavior" (in en). Aggressive Behavior 34 (4): 404–415. doi:10.1002/ab.20252. ISSN 1098-2337. PMID 18351598.

- ↑ Buss, David M.; Dedden, Lisa A. (1990-08-01). "Derogation of Competitors" (in en). Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 7 (3): 395–422. doi:10.1177/0265407590073006. ISSN 0265-4075.

- ↑ Campell, Anne; Gibbs, John J., eds (1986). Violent transactions: the limits of personality. New York, USA: Blackwell.

- ↑ Campbell, Anne (1995-03-01). "A few good men: Evolutionary psychology and female adolescent aggression". Ethology and Sociobiology 16 (2): 99–123. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(94)00072-F.

- ↑ Schmitt, David P.; Buss, David M. (1996). "Strategic self-promotion and competitor derogation: Sex and context effects on the perceived effectiveness of mate attraction tactics.". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70 (6): 1185–1204. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1185. PMID 8667162.

- ↑ Fisher, Maryanne; Cox, Anthony; Gordon, Fiona (2009-12-01). "Self-promotion versus competitor derogation: the influence of sex and romantic relationship status on intrasexual competition strategy selection". Journal of Evolutionary Psychology 7 (4): 287–308. doi:10.1556/JEP.7.2009.4.6. ISSN 1789-2082.

- ↑ Arnocky, Steven; Vaillancourt, Tracy (2012-04-01). "A Multi-Informant Longitudinal Study on the Relationship between Aggression, Peer Victimization, and Dating Status in Adolescence" (in en). Evolutionary Psychology 10 (2): 147470491201000207. doi:10.1177/147470491201000207. ISSN 1474-7049.

- ↑ Gallup, Andrew C.; O'Brien, Daniel T.; Wilson, David Sloan (2011-05-01). "Intrasexual peer aggression and dating behavior during adolescence: an evolutionary perspective" (in en). Aggressive Behavior 37 (3): 258–267. doi:10.1002/ab.20384. ISSN 1098-2337. PMID 21433032.

- ↑ Pellegrini, Anthony D.; Long, Jeffrey D. (2003-07-01). "A sexual selection theory longitudinal analysis of sexual segregation and integration in early adolescence". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 85 (3): 257–278. doi:10.1016/s0022-0965(03)00060-2. ISSN 0022-0965. PMID 12810038.

- ↑ White, Daniel D.; Gallup, Andrew C.; Gallup, Gordon G. (2010-01-01). "Indirect peer aggression in adolescence and reproductive behavior". Evolutionary Psychology 8 (1): 49–65. doi:10.1177/147470491000800106. ISSN 1474-7049. PMID 22947779.

- ↑ Fisher, M. (2015). "Women's competition for mates: Experimental findings leading to ethological studies.". Human Ethology Bulletin 30: 53–70. http://ishe.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/HEB_2015_30_1_53-70.pdf.

- ↑ Buss, David M. (1989). "Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures". Behavioral and Brain Sciences 12 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1017/s0140525x00023992.

- ↑ Palombit, R.A.; Cheney, D.L.; Seyfarth, R.M. (2001). "Female–female competition for male 'friends' in wild chacma baboons (Papio cynocephalus ursinus)". Animal Behaviour 61 (6): 1159–1171. doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1690. ISSN 0003-3472.

- ↑ Geary, David C. (2005). "Evolution of life-history trade-offs in mate attractiveness and health: Comment on Weeden and Sabini (2005).". Psychological Bulletin 131 (5): 654–657. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.654. PMID 16187850.

- ↑ Weeden, Jason; Sabini, John (2005). "Physical Attractiveness and Health in Western Societies: A Review.". Psychological Bulletin 131 (5): 635–653. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.635. PMID 16187849.

- ↑ "Are high-quality mates always attractive?: State-dependent mate preferences in birds and humans". Commun Integr Biol 3 (3): 271–3. 2010. doi:10.4161/cib.3.3.11557. PMID 20714411.

- ↑ Buston, P. M.; Emlen, S. T. (2003). "Cognitive processes underlying human mate choice: The relationship between self-perception and mate preference in Western society". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100 (15): 8805–8810. doi:10.1073/pnas.1533220100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 12843405. Bibcode: 2003PNAS..100.8805B.

- ↑ Todd, P. M.; Penke, L.; Fasolo, B.; Lenton, A. P. (2007). "Different cognitive processes underlie human mate choices and mate preferences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 (38): 15011–15016. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705290104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 17827279. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..10415011T.

- ↑ Little, A. C.; Burt, D. M.; Penton-Voak, I. S.; Perrett, D. I. (2001). "Self-perceived attractiveness influences human female preferences for sexual dimorphism and symmetry in male faces". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 268 (1462): 39–44. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1327. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 12123296.

- ↑ Rucas, Stacey L.; Gurven, Michael; Kaplan, Hillard; Winking, Jeff; Gangestad, Steve; Crespo, Maria (2006-01-01). "Female intrasexual competition and reputational effects on attractiveness among the Tsimane of Bolivia" (in en). Evolution and Human Behavior 27 (1): 40–52. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.07.001. ISSN 1090-5138.

- ↑ Stockley, Paula; Bro-Jørgensen, Jakob (2011). "Female competition and its evolutionary consequences in mammals". Biological Reviews 86 (2): 341–366. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00149.x. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 20636474.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Archer, John (2006). "Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 30 (3): 319–345. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.12.007. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 16483890.

- ↑ Dabbs, James M.; Hargrove, Marian F.; Heusel, Colleen (1996). "Testosterone differences among college fraternities: well-behaved vs rambunctious". Personality and Individual Differences 20 (2): 157–161. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(95)00190-5. ISSN 0191-8869.

- ↑ French, J. A.; Mustoe, A. C.; Cavanaugh, J.; Birnie, A. K. (2013). "The influence of androgenic steroid hormones on female aggression in 'atypical' mammals". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 368 (1631): 20130084. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0084. ISSN 0962-8436. PMID 24167314.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Miller, Saul L.; Maner, Jon K.; McNulty, James K. (2012). "Adaptive attunement to the sex of individuals at a competition: the ratio of opposite- to same-sex individuals correlates with changes in competitors' testosterone levels". Evolution and Human Behavior 33 (1): 57–63. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2011.05.006. ISSN 1090-5138.

- ↑ Buss, David M. (1988). "The evolution of human intrasexual competition: Tactics of mate attraction.". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54 (4): 616–628. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.4.616. ISSN 0022-3514. PMID 3367282. https://www.academia.edu/download/35430302/evolution_intrasexual_competition_1988_jpsp.pdf.[|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ López, Hassan H.; Hay, Aleena C.; Conklin, Phoebe H. (2009). "Attractive men induce testosterone and cortisol release in women". Hormones and Behavior 56 (1): 84–92. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.004. ISSN 0018-506X. PMID 19303881.

- ↑ Booth, Alan; Shelley, Greg; Mazur, Allan; Tharp, Gerry; Kittok, Roger (1989). "Testosterone, and winning and losing in human competition". Hormones and Behavior 23 (4): 556–571. doi:10.1016/0018-506X(89)90042-1. ISSN 0018-506X. PMID 2606468.

- ↑ Mccaul, K (1992). "Winning, losing, mood, and testosterone". Hormones and Behavior 26 (4): 486–504. doi:10.1016/0018-506X(92)90016-O. ISSN 0018-506X. PMID 1478633.

- ↑ van der Meij, Leander; Buunk, Abraham P.; Almela, Mercedes; Salvador, Alicia (2010). "Testosterone responses to competition: The opponent's psychological state makes it challenging". Biological Psychology 84 (2): 330–335. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.03.017. ISSN 0301-0511. PMID 20359521.

- Huddergs, L., De Backer, C., Fisher, M., & Vyncke, P. (2014). The Rival Wears Prada: Luxury Consumption as a Female Competition Strategy. Evolutionary

- Singh, D. (2011). "Shape and Significance of Feminine Beauty: An Evolutionary Perspective". Sex Roles 64 (9–10): 723–731. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9938-z.

|