Philosophy:Theosophy and literature

According to some literary and religious studies scholars, modern Theosophy had a certain influence on contemporary literature,[1][2] particularly in forms of genre fiction such as fantasy and science fiction.[3][4] Researchers claim that Theosophy has significantly influenced the Irish literary renaissance of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, notably in such figures as W. B. Yeats and G. W. Russell.[5][6][7]

Classic writers and Theosophists

Dostoevsky

In November 1881, Helena Blavatsky, editor in chief of The Theosophist, started publishing her translation into English of "The Grand Inquisitor" from Book V, chapter five of Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov.[8][note 1][note 2]

In a small commentary which preceded the beginning of the publication, she explained that "the great Russian novelist" Dostoevsky died a few months ago, making the "celebrated" novel The Brothers Karamazov his last work. She described the passage as a "satire" on modern theology in general and on the Roman Catholic Church in particular. As described by Blavatsky, "The Grand Inquisitor" imagines the Second Coming of Christ occurring in Spain during the time of the Inquisition. Christ is at once arrested as a heretic by the Grand Inquisitor. The legend, or "poem", is created by the character Ivan Karamazov, a materialist and an atheist, who tells it to his younger brother Alyosha, an immature Christian mystic."[10][note 3]

According to Brendan French, a researcher in esotericism, "it is highly significant" that [exactly 8 years after her publication of "The Grand Inquisitor"] Blavatsky declared Dostoevsky to be "a theosophical writer."[12] In her article about the approach of a new era in both society and literature, called "The Tidal Wave", she wrote:

"[The root of evil lies, therefore, in a moral, not in a physical cause.] If asked what is it then that will help, we answer boldly:—Theosophical literature; hastening to add that under this term, neither books concerning adepts and phenomena, nor the Theosophical Society publications are meant... What the European world now needs is a dozen writers such as Dostoyevsky, the Russian author... It is writers of this kind that are needed in our day of reawakening; not authors writing for wealth or fame, but fearless apostles of the living Word of Truth, moral healers of the pustulous sores of our century... To write novels with a moral sense in them deep enough to stir Society, requires a literary talent and a born Theosophist as was Dostoyevsky."[13][14]

Tolstoy

When Leo Tolstoy was working on his book The Thoughts of Wise People for Every Day,[15] he used a magazine of the Theosophical Society of Germany Theosophischer Wegweiser. He extracted eight aphorisms of the Indian sage Ramakrishna, eight from The Voice of the Silence[16] by Blavatsky, and one of fellow Theosophist Franz Hartmann, from the issues of 1902 and 1903, and translated them into Russian.[17] Tolstoy had in his library the English edition of The Voice of the Silence, which had been presented to him by its author.[18][note 4]

In November 1889, Blavatsky published her own English translation of Tolstoy's fairy tale "How A Devil's Imp Redeemed His Loaf, or The First Distiller",[20] which was accompanied by a small preface about the features of translation from Russian. Calling Tolstoy "the greatest novelist and mystic of Russia of to-day," she wrote that all his best works had already been translated, but that the attentive Russian reader would not find the "popular national spirit" that permeates all original stories and fairy tales, in any of these translations. Despite the fact that they are full of "popular mysticism", and some of them are "charming", they are the most difficult to translate into a foreign language. She concluded: "No foreign translator, however able, unless born and bred in Russia and acquainted with Russian peasant life, will be able to do them justice, or even to convey to the reader their full meaning, owing to their absolutely national idiomatic language."[21]

In September 1890, Blavatsky published philosopher Raphael von Koeber's article "Leo Tolstoi and his Unecclesiastical Christianity" in her magazine Lucifer.[22] Prof. von Koeber briefly described the merits of Tolstoy as a great master of artistic language, but the main focus of the article was Tolstoy's search for answers to religious and philosophical questions. The author concluded that Tolstoу's "philosophy of life" is identical in its foundation to that of Theosophy.[23]

Theosophist Charles Johnston, president of the New York branch of the Irish Literary Society,[24] Johnston travelled to Russia and met with Tolstoy. In March 1899 Johnston published "How Count Tolstoy Writes?"[25] in the American magazine The Arena. In November 1904, Rudolf Steiner gave a lecture in Berlin entitled "Theosophy and Tolstoy",[26] where he discussed the novels War and Peace, Anna Karenina, the novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich, and the philosophical book On Life (1886–87).[27]

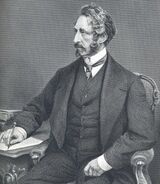

Yeats

| Poem by W. B. Yeats | |

Yeats became interested in Theosophy in 1884, after reading Esoteric Buddhism by Alfred Percy Sinnett. A copy of the book was sent him by his aunt, Isabella Varley. Together with his friends George Russell[35][note 7] and Charles Johnston,[33] he established the Dublin Hermetic Society, which would later become the Irish section of the Theosophical Society.[37] According to Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (EOP), Yeats's tendency toward mysticism was "stimulated" by the religious philosophy of the Theosophical Society.[38]

In 1887, Yeats's family moved to London, where he was introduced to Blavatsky by his friend Johnston.[39] In her external appearance she reminded him of "an old Irish peasant woman". He recalled her massive figure, constant cigarette smoking, and unceasing work at her writing desk which, he claimed, "she did for twelve hours a day." He respected her "sense of humor, her dislike of formalism, her abstract idealism, and her intense, passionate nature." At the end of 1887, she officially founded the Blavatsky Lodge of the Theosophical Society in London. Yeats entered into the Esoteric Section of the Lodge in December 1888 and became a member of the "Recording Committee for Occult Research" in December 1889. In August 1890, to his great regret, he was expelled from the Society for undertaking occult experiments forbidden by the Theosophists.[40][41][42]

According to The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (EF), Yeats wrote extensively on mysticism and magic.[43] In 1889 he published an article—"Irish Fairies, Ghosts, Witches, etc."[44][41]—in Blavatsky's journal, and another in 1914—"Witches and Wizards and Irish Folk-Lore".[45] Literary scholar Richard Ellmann wrote of him:

"Yeats found in occultism, and in mysticism generally, a point of view which had the virtue of warring with accepted belief... He wanted to secure proof that experimental science was limited in its results, in an age when science made extravagant claims; he wanted evidence that an ideal world existed, in an age which was fairly complacent about the benefits of actuality; he wanted to show that the current faith in reason and in logic ignored a far more important human faculty, the imagination."[46][47]

Poetry and mysticism

According to Gertrude Marvin Williams, British poet Alfred Tennyson was reading Blavatsky's "mystical poem" The Voice of the Silence in the last days of his life.[48][49]

In his article on Blavatsky, Prof. Russell Goldfarb[note 8] mentions a lecture by American psychologist and philosopher William James in which he said that "mystical truth spoke best as musical composition rather than as conceptual speech."[51] As evidence for this, James cited this passage from The Voice of the Silence in his book The Varieties of Religious Experience:

"He, who would hear the voice of Nada, 'the Soundless Sound,'

and comprehend it, he has to learn the nature of Dhāranā...

When to himself his form appears unreal,

as do on waking all the forms he sees in dreams;

when he has ceased to hear the many, he may discern

the One—the inner sound which kills the outer...

For then the soul will hear, and will remember.

And then to the inner ear will speak

The Voice Of The Silence...

And now thy Self is lost in Self,

thyself unto Thyself, merged in

that Self from which thou first didst radiate...

Behold! thou hast become the Light, thou has become the Sound,

thou art thy Master and thy God.

Thou art Thyself the object of thy search;

the Voice unbroken, that resounds throughout eternities,

exempt from change, from sin exempt,

the seven sounds in one,

the Voice Of The Silence.

Om tat Sat."

In Buddhist writer Dennis Lingwood's opinion, the author of The Voice of the Silence (abbreviated VS) "seeks more to inspire than to instruct, appeals to the heart rather than to the head."[55] A researcher of NRM Arnold Kalnitsky wrote that, in spite of inevitable questions on the origins and authorship of VS,[note 10] the "authenticity of the tone of the teachings and the expression of the sentiments" have risen above the Theosophical and occult environment, receiving "independent respect" from such authorities as William James, D. T. Suzuki and others.[57]

Russian esotericist P. D. Ouspensky affirmed that VS has a "very special" position in modern mystical literature, and used several quotes from it in his book Tertium Organum to demonstrate "the wisdom of the East."[58] Writer Howard Murphet has called VS a "little gem", noting that its poetry "is rich in both imagery and mantra-like vibrations."[59] Annie Besant characterized the language of VS as "perfect and beautiful English, flowing and musical."[60]

In Prof. Robert Ellwood's opinion, the book is a "short mystical devotional work of rare beauty."[61] Other scholars of religious studies have suggested that: a rhythmic modulation in VS supports "the feeling of mystical devotion";[62] the questions illumined in VS are "explicitly devoted to the attainment of mystical states of consciousness";[63] and that VS is among the "most spiritually practical works produced by Blavatsky."[64]

William James said of mysticism that: "There is a verge of the mind which these things haunt; and whispers therefrom mingle with the operations of our understanding, even as the waters of the infinite ocean send their waves to break among the pebbles that lie upon our shores."[53]

Theosophical fiction

Forerunner

According to scholar Brendan French, novels by authors in the Rosicrucian tradition are a path to the "conceptual domain" of Blavatsky.[66] He notes that Zanoni (1842)[67] by Edward Bulwer-Lytton[68][69] is "undoubtedly the apogee of the genre". It was this novel that later had the greatest impact on the elaboration of the concept of the Theosophical mahatmas. French quoted Blavatsky as saying: "No author in the world of literature ever gave a more truthful or more poetical description of these beings than Sir E. Bulwer-Lytton, the author of Zanoni." [70][71]

This novel is especially important for followers of occultism because of "the suspicion—actively fostered by its author—that the work is not a fictional account of a mythical fraternity, but an accurate depiction of a real brotherhood of immortals."[72] According to EF, Bulwer-Lytton's character the "Dweller on the Threshold"[73] has since become widely used by followers of Theosophy[74][75] and authors of "weird fiction".[76]

A second important novel for Theosophists by Bulwer-Lytton is The Coming Race[77] published in 1871.[78][79]

Theosophists as fiction writers

According to French, Theosophy has contributed much to the expansion of occultism in fiction. Not only were Theosophists writing occult fiction, but many professional authors who were prone to mysticism joined the Theosophical Society.[80] Russian literary scholar Anatoly Britikov wrote that "Theosophical myth is beautiful and poetic" because its authors had an "extraordinary talent for fiction", and borrowed their ideas from works of "high literary value."[81]

In John Clute's opinion, Blavatsky's own fiction, most of which was published in 1892 in the collection Nightmare Tales,[82][83] is "unimportant".[note 11] However, her main philosophical works, Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine, can be considered as rich sources that contain "much raw material for creators of fantasy worlds".[3] He wrote that in its content, supported by an attendant entourage that intensifies its effect, Theosophy is a "sacred drama, a romance, a secret history" of the world. Those whose souls are "sufficiently evolved to understand that drama know the tale is enacted in another place, beyond the threshold... within a land exempt from secular accident."[4][note 12]

In Prof. Antoine Faivre's opinion, Ghost Land, or Researches into the Mysteries of Occultism[86] by Emma Hardinge Britten,[87][79] one of the founders of the Theosophical movement, is "one of the principal works of fiction inspired by the occultist current".[69]

Mabel Collins,[note 13] who helped Blavatsky edit the Theosophical journal Lucifer in London, wrote a book entitled The Blossom and the Fruit: A True Story of a Black Magician (1889).[89] According to EOP the book demonstrated her growing interest in metaphysics and occultism.[88] After leaving editorial work, however, she published several books[note 14] that parodied Blavatsky and her Masters.[91][92]

Franz Hartmann has published several fiction works: An Adventure among the Rosicrucians (1887),[93][note 15] the Theosophical satire The Talking Image of Urur (1890),[95] and Among the Gnomes (1895)[96]—a satire on those who immediately deny everything "supernatural".[97] Russian philologist Alexander Senkevich noted that Blavatsky perfectly understood that the titular 'Talking Image' was her "caricatured persona", but nevertheless continued publishing the novel in her magazine for many months.[98] In the foreword to the first edition its author proclaimed that the characters of the novel are "so to say, composite photographs of living people", and that it was created "with the sole object of showing to what absurdities a merely intellectual research after spiritual truths will lead."[99][100][note 16] "The end of Hartmann's novel is unexpected. The evil forces that held the 'Talking Image' weaken, and it is freed from the darkening of consciousness. The author's final conclusion is quite a Buddhist one: 'Search for the truth yourself: do not entrust this to someone else'."[98]

The Theosophical leaders William Quan Judge,[101] Charles Webster Leadbeater,[102] Anna Kingsford,[103] and others wrote so-called "weird stories".[104][84] In his fiction collection, Leadbeater gave a brief description of Blavatsky as a storyteller of occult tales: "She held her audience spell-bound, she played on them as on an instrument and made their hair rise at pleasure, and I have often noticed how careful they were to go about in couples after one of her stories, and to avoid being alone even for a moment!"[105][106] The novel Karma by Alfred Sinnett[107] is, in essence, a presentation of the Theosophical doctrines of karma and reincarnation, using knowledge of past lives and the present karma of the leading characters.[108][92] His next occult novel United, [109][110] was published in 1886 in 2 volumes.[note 17]

A trilogy The Initiate (1920–32)[112] by Cyril Scott was extremely popular and reprinted several times. In it the author expounds his understanding of the Theosophical doctrine, using fictional characters alongside real ones.[113][114]

Fiction writers and Theosophy

In 1887, Blavatsky published the article "The Signs of the Times", in which she discussed the growing influence of Theosophy in literature. She listed some novels that can be categorized as Theosophical and mystical literature, including Mr Isaacs[115] (1882) and Zoroaster[116] (1885) by Francis Marion Crawford;[117] The Romance of Two Worlds[118] (1886) by Marie Corelli;[119] The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde[120] (1886) by Robert Louis Stevenson;[note 18] A Fallen Idol[122] (1886) by F. Anstey;[123] King Solomon's Mines[124] (1885) and She: A History of Adventure[125] (1887) by H. Rider Haggard;[78] Affinities[126] (1885) and The Brother of the Shadow[127] (1886) by Rosa Campbell Praed; A House of Tears[128] (1886) by Edmund Downey;[129] and A Daughter of the Tropics[130] (1887) by Florence Marryat.[131][132]

According to EOP, the prototype for the main character of Crawford's novel Mr Isaacs was someone called Mr. Jacob, a Hindu mage of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[133] Blavatsky was particularly charmed by Crawford's Ram Lal, a character akin to Bulwer-Lytton's Mejnour or Koot Hoomi of the Theosophists. Ram Lal says of himself: "I am not omnipotent. I have very little more power than you. Given certain conditions I can produce certain results, palpable, visible, and appreciable by all; but my power, as you know, is itself merely the knowledge of the laws of nature, which Western scientists, in their ignorance, ignore."[134][135][136] According to EF, this book informs readers about some of the teachings of Theosophy.[117]

Rosa Campbell Praed[137] was interested in spiritualism, occultism, and Theosophy, and made the acquaintance of many Theosophists who, as French pointed out, "inevitably became characters in her novels". He wrote: "Praed was especially influenced by her meeting in 1885 with Mohini Chatterji (who became the model for Ananda in The Brother of the Shadow)."[138][note 19]

French wrote that figures of the Theosophical mahatmas appear in several of the most popular novels of Marie Corelli, including her first book The Romance of Two Worlds (1886). A similar theme is present in A Fallen Idol (1886) by F. Anstey.[139]

According to EOP, the author of occult novels Algernon Blackwood specialized in literature describing psychic phenomena and ghosts.[140][141] In their article "Theosophy and Popular Fiction", the esotericism researchers Gilhus and Mikaelsson point out that in his novel The Human Chord[142] (1910), Blackwood warns readers about the dangers of occult experiments.[143]

Gustav Meyrink's novel [144] The Golem[145] (1914) is mentioned by many researchers of esotericism.[146][2][79] Writer Talbot Mundy[2] created his works on the basis of the Theosophical assumption that various forms of occultism exist as evidence of the ancient wisdom that is preserved at the present time, thanks to the secret brotherhood of adepts.[147][148][114]

Characters whose prototype was Blavatsky

- Mme Tamvaco in a novel by Rosa Campbell Praed Affinities[126][149]

- Image of Urur in a novel by Franz Hartmann The Talking Image of Urur[95][91][98]

- Maya in the story of the same name by Vera Zhelikhovsky[150][note 20]

- Mme Petrovna in a novel by William Lincoln Garver Brother of the Third Degree[151][note 21]

- Mme Sosostris in a poem by T. S. Eliot The Waste Land[153][154][155]

- Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in a novel by Mark Frost The List of 7[156][3][157]

- Natalia Vladimirovna Andreyeva in a novel by Concordia Antarova Two Lives[158]

Bibliography

- Allen, F. M. (1886). A House of Tears. https://books.google.com/books?id=aWdMtQEACAAJ.

- Anstey, F. (1886). A Fallen Idol. https://archive.org/details/fallenidol00anst.

- Blackwood, A. (1910). The Human Chord. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11988.

- Blavatsky, H. P. (1889). The Voice of the Silence. http://blavatskyarchives.com/theosophypdfs/blavatsky__the_voice_of_the_silence_1889.pdf.

- Britten, E. H. (1876). Ghost Land, or Researches into the Mysteries of Occultism. http://www.ehbritten.org/texts/primary/ehb_ghost_land_first_edition.pdf.

- Collins, M. (1889). The Blossom and the Fruit: A True Story of a Black Magician. New York, J.W. Lovell company. https://archive.org/details/blossomandfruit01collgoog.

- Corelli, M. (1886). A Romance of Two Worlds. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4394. ()

- Crawford, F. M. (1882). Mr Isaacs. New York, Collier. https://archive.org/details/completeworksoff01crawrich.

- Dostoevsky, F. (1880). The Grand Inquisitor. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/8578.

- Eliot, T. S. (1922). The Waste Land. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1321.

- Flammarion, C. (1889). Urania. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/41941.[159][note 22]

- Frost, M. (1993). The List of 7.

- Garver, W. L. (1894). Brother of the Third Degree. https://www.globalgreyebooks.com/content/books/ebooks/brother-of-the-third-degree.pdf.

- Haggard, H. R. (1885). King Solomon's Mines. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2166.

- Hartmann, F. (1887). An Adventure among the Rosicrucians. Occult Pub. Co.. https://archive.org/details/anadventureamon00hartgoog.

- Judge, W. Q. (1893). Occult Tales. https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/wqjtales/tales-hp.htm.

- Kingsford, A. (1875). Rosamunda the Princess, and Other Tales. https://archive.org/details/rosamundaprince00kinggoog.

- Leadbeater, C. W. (1911). The Perfume of Egypt and other Weird Stories. http://www.anandgholap.net/Perfume_Of_Egypt-CWL.htm.

- Lytton, B. (1842). Zanoni. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2664.

- Marryat, F. (1887). A Daughter of the Tropics. https://books.google.com/books?id=4xRMuAEACAAJ.

- Meyrink, G. (1914) (in de). Der Golem. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/51476.

- Mundy, T. (1924). Om: The Secret of Ahbor Valley. http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks05/0500271h.html.

- Praed, R. C. (1885). Affinities. G. Routledge and Sons. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/012192117.

- Scott, C. M. (1920). The Initiate. https://archive.org/details/initiatesomeimpr00scot. (1st part)

- Sinnett, A. P. (1885). Karma: A Novel. https://archive.org/details/karmanovel00sinnrich.

- Stevenson, R. L. (1886). The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/42.

- Tolstoy, L. N. (1889). How A Devil's Imp Redeemed His Loaf, or The First Distiller. http://www.katinkahesselink.net/blavatsky/articles/v12/y1889_073.htm.

- Yeats, W. B. (1889). Irish Fairies, Ghosts, Witches, etc.. http://www.iapsop.com/archive/materials/lucifer/lucifer_v3_n17_january_1889.

- In Russian

- Достоевский, Ф. М. (in ru). Великий инквизитор. http://www.e-reading.by/chapter.php/98717/81/Dostoevskiii_09_Tom_9._Brat%27ya_Karamazovy.html. (1980)

- Желиховская, В. П. (in ru). Майя. http://www.e-reading.by/book.php?book=1052641. (1893)

- Толстой, Л. Н. (in ru). Как чертёнок краюшку выкупал. http://www.e-reading.by/chapter.php/97272/275/Tolstoii_10_Tom_10._Proizvedeniya_1872-1886_gg.html. (1886)

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Blavatsky was so impressed by Dostoevskii's The Brothers Karamazov that she translated... 'The Grand Inquisitor' for publication in The Theosophist."[9]

- ↑ In Brendan French's opinion, it is difficult to assume that, apart from Blavatsky, anyone else translated Dostoevsky into English until 1912, when a translation by Constance Garnett was issued.[9]

- ↑ After the first publication in 1881, Blavatsky's translation was reprinted several times.[11]

- ↑ Maria Carlson stated that Tolstoy liked Blavatsky's "devotional work", The Voice of the Silence, and was familiar with several of the leading Theosophists.[19]

- ↑ It has been first published in 1929 under the title "Meditations upon Death," one was reissued in 1932 as "Mohini Chatterji."[30]

- ↑ In 1885, a Hindu Theosophist Mohini Chatterji has paid visit into Dublin at the invitation of the Hermetic Society, which president was Yeats.[32][33][34]

- ↑ An Irish writer George Russell, Yeats's friend, was "a life-long Theosophist."[36]

- ↑ "Russell M. Goldfarb is a professor of English at Western Michigan University."[50]

- ↑ "Om Tat Sat, a Sanskrit mantra meaning 'Om that is being.' Sacred words that are used to invoke a deity."[54]

- ↑ Blavatsky was, as she claimed, only a translator of the ancient text.[56]

- ↑ Almost all of her stories are about psychic phenomena, karma, reincarnation, and secrets.[84]

- ↑ Russian literary critic Zinaida Vengerova complimented Blavatsky as an artist of the word, although she considered only her Russian publications.[85]

- ↑ "An important but shadowy figure in the Theosophical Society during the latter part of the nineteenth century."[88]

- ↑ In particular, Morial the Mahatma, or The Black Master of Tibet (1892)[90]

- ↑ Blavatsky called this work by Hartmann an unusual and strange story, "full of poetic feeling" which, moreover, contains "deep philosophical and occult truths."[94]

- ↑ The real figures of the Theosophical history, who served as the prototypes for Hartmannn's characters, are viewed quite easily in the novel: Image of Urur, a mediator between the Society for Distribution of Wisdom and a Mysterious Brotherhood of Adepts— Helena Blavatsky; captain Bumpkins—colonel Henry Olcott; Mr. Puffer—Alfred Percy Sinnett, Mme. and Mssr. Corneille—Mme. and Mssr. Coulomb; Rev. Sniff—Rev. George Patterson; Mr. Bottler, a representative of the Society for the Discovery of Unknown Sciences—Hodgson from the Society for Psychical Research, etc.

- ↑ Blavatsky called this novel a "remarkable work", not only because of its "undeniable" literary merits, but also because of its "psychic" qualities.[111]

- ↑ In Blavatsky's opinion, Stevenson had a "glimpse of a true vision" when he wrote his novel which should be considered as a "true allegory." Every student of occultism would recognize in Mr. Hyde an "obsessor of the personality."[121]

- ↑ According to EF, Blavatsky's ideas "provide the basis for the brief but wholehearted Theosophical fantasy" The Brother of the Shadow (1886) by Mrs Praed.[137]

- ↑ See the comments for the 2017 reprint.[150]

- ↑ "Garver's portrait of Madame Petrovna is a clear literary replica of Blavatsky."[152]

- ↑ A French astronomer and writer Camille Flammarion was a member of the Theosophical Society.

References

- ↑ Goldfarb 1971, p. 671.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Santucci 2012, p. 240.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Clute 1997b.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Clute 1999.

- ↑ Goldfarb 1971, p. 666.

- ↑ Sellon & Weber 1992, p. 327.

- ↑ Melton 2001b, p. 196.

- ↑ Dostoevsky 1880.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 French 2000, p. 444.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1968.

- ↑ WorldCat.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 443.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1980a, pp. 6–8.

- ↑ French 2000, pp. 443–444.

- ↑ Толстой 1903.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1889, pp. 25, 31, 54, 61–62.

- ↑ Толстой 1956, p. 482.

- ↑ Ласько 2004.

- ↑ Carlson 2015, p. 161.

- ↑ Tolstoy 1889.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1889a.

- ↑ Koeber 1890.

- ↑ Koeber 1890, pp. 9, 14.

- ↑ McCready 1997c, p. 206.

- ↑ Johnston 2014.

- ↑ Steiner 1904.

- ↑ Толстой 1887.

- ↑ Yeats 1929.

- ↑ Monteith 2014, pp. 21–6.

- ↑ Ross 2014, p. 159.

- ↑ McCready 1997b.

- ↑ Ellmann 1987, p. 44.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 McCready 1997c.

- ↑ Singh 2012.

- ↑ Melton 2001h.

- ↑ Monteith 2014, p. 216.

- ↑ Ross 2014, p. 565.

- ↑ Melton 2001i.

- ↑ McCready 1997c, p. 205.

- ↑ Ellmann 1987, p. 69.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 McCready 1997a, p. 41.

- ↑ Ross 2014, p. 566.

- ↑ Ashley 1997d.

- ↑ Yeats 1889.

- ↑ Yeats 1914.

- ↑ Ellmann 1964, p. 3.

- ↑ Goldfarb 1971, p. 667.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1889.

- ↑ Williams 1946, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Goldfarb 1971, p. 672.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Goldfarb 1971, p. 669.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1889, pp. 1–3, 20–22.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 James 1929, p. 412.

- ↑ Theosopedia 2012.

- ↑ Sangharakshita 1958, p. 1.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1889, p. vi.

- ↑ Kalnitsky 2003, p. 329.

- ↑ Успенский 1911, Гл. 20.

- ↑ Murphet 1975, p. 241.

- ↑ Besant 2011, p. 353.

- ↑ Ellwood 2014, p. 219.

- ↑ Kuhn 1992, p. 272.

- ↑ Kalnitsky 2003, p. 323.

- ↑ Rudbøg 2012, p. 406.

- ↑ Introvigne 2018, p. 13.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 557.

- ↑ Lytton 1842.

- ↑ Melton 2001g.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Faivre 2010, p. 88.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1877, p. 285.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 562.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 585.

- ↑ Godwin 1994, p. 129.

- ↑ Ashley 1997a.

- ↑ Purucker 1999.

- ↑ Clute 1997e.

- ↑ Lytton 1871.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Melton 2001e, p. 558.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 Hanegraaff 2013, p. 151.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 662.

- ↑ Бритиков 1970, p. 60.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1892.

- ↑ Шабанова 2016, p. 66.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Gilhus & Mikaelsson 2013, p. 456.

- ↑ Венгерова & Соловьёв 1892, pp. 301–315.

- ↑ Britten 1876.

- ↑ Melton 2001c.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Melton 2001d.

- ↑ Collins 1889.

- ↑ Collins 1892.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 French 2000, p. 671.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Gilhus & Mikaelsson 2013, p. 457.

- ↑ Hartmann 1887.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1960, p. 130.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Hartmann 1890.

- ↑ Hartmann 1895.

- ↑ Zirkoff 1960, pp. 453–5.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 Сенкевич 2012, p. 418.

- ↑ Hartmann 1890, p. viii.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 672.

- ↑ Judge 1893.

- ↑ Leadbeater 1911.

- ↑ Kingsford 1875.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 2013, p. 150.

- ↑ Leadbeater 1911, p. 138.

- ↑ Gilhus & Mikaelsson 2013, pp. 456–457.

- ↑ Sinnett 1885.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 667.

- ↑ Sinnett 1886a.

- ↑ Sinnett 1886b.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1958, p. 306.

- ↑ Scott 1920.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 728.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 Gilhus & Mikaelsson 2013, p. 459.

- ↑ Crawford 1882.

- ↑ Crawford 1885.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Ashley 1997c.

- ↑ Corelli 1886.

- ↑ Ashley 1997b.

- ↑ Stevenson 1886.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1980b, pp. 636–7.

- ↑ Anstey 1886.

- ↑ Larson 1997.

- ↑ Haggard 1885.

- ↑ Haggard 1887.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 Praed 1885.

- ↑ Praed 1886.

- ↑ Allen 1886.

- ↑ Clute 1997a.

- ↑ Marryat 1887.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1887, p. 83.

- ↑ French 2000, pp. 663–664.

- ↑ Melton 2001f.

- ↑ Crawford 1882, p. 300.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1883, p. 125.

- ↑ French 2000, pp. 664–665.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 Stableford 1997.

- ↑ French 2000, pp. 665–6.

- ↑ French 2000, pp. 669–70.

- ↑ Melton 2001a.

- ↑ Melton 2001e, p. 559.

- ↑ Blackwood 1910.

- ↑ Gilhus & Mikaelsson 2013, p. 465.

- ↑ Clute 1997c.

- ↑ Meyrink 1914.

- ↑ Faivre 2010, p. 104.

- ↑ Mundy 1924.

- ↑ Clute 1997d.

- ↑ Sasson 2012, p. 103.

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 Желиховская 1893.

- ↑ Garver 1894.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 677.

- ↑ Eliot 1922.

- ↑ Goldfarb 1971, p. 668.

- ↑ Breen 2014, p. 110.

- ↑ Frost 1993.

- ↑ Gilhus & Mikaelsson 2013, p. 470.

- ↑ Abbasova 2015.

- ↑ Clute & Sterling 1999.

Sources

- Melton, J. G., ed (2001a). "Blackwood, Algernon (Henry) (1869–1951)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 192. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-O9xQAAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Melton, J. G., ed (2001b). "Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna (1831–1891)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 194–6. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-O9xQAAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Melton, J. G., ed (2001c). "Britten, Emma Hardinge (1823–1899)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 218–19. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-O9xQAAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Melton, J. G., ed (2001d). "Collins, Mabel (Mrs. Keningale Cook) (1851–ca. 1922)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 310–11. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-O9xQAAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Melton, J. G., ed (2001e). "Fiction, English Occult". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 557–60. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-O9xQAAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Melton, J. G., ed (2001f). "Jacob, Mr. ("Jacob of Simla") (ca. 1850–1921)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 819. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-O9xQAAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Melton, J. G., ed (2001g). "Lytton, Bulwer (1803–1873)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 948–9. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-O9xQAAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Melton, J. G., ed (2001h). "Russell, George W(illiam) (1867–1935)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 1333. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-O9xQAAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Melton, J. G., ed (2001i). "Yeats, W(illiam) B(utler) (1865–1939)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 1696. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-O9xQAAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Purucker, G. de, ed (1999). "Dweller on the Threshold". Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary. Theosophical University Press. ISBN 978-1-55700-141-2. https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/etgloss/dis-dz.htm. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- "Formats and editions of The Grand Inquisitor". WorldCat. https://www.worldcat.org/title/grand-inquisitor/oclc/659874336/editions?referer=di&editionsView=true.

- "Om Tat Sat". Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. 30 March 2012. http://theosophy.ph/encyclo/index.php?title=Om_Tat_Sat.

- Abbasova, Pyarvin (Summer 2015). "HPB in Today's Russia". Quest (Wheaton, Illinois: Theosophical Publishing House) 103 (3): 112–113. https://www.theosophical.org/publications/quest-magazine/3618. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- Ashley, M. (1997a). "Bulwer-Lytton, [Sir Edward, First Baron Lytton"]. in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=bulwer-lytton_edward_first_baron_lytton. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Ashley, M. (1997b). "Corelli, Marie". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=corelli_marie. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Ashley, M. (1997c). "Crawford, F. Marion". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=crawford_f_marion. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Ashley, M. (1997d). "Yeats, William Butler". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=yeats_william_butler. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Besant, A. (2011). Annie Besant: An Autobiography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108027311. https://books.google.com/books?id=ey9hPV9brxoC. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Blavatsky, H. P. (1877). Isis Unveiled. 1. New York: J. W. Bouton. http://www.phx-ult-lodge.org/isis_unveiled1.htm.

- Breen, B. (April 2014). Breen, B.. ed. "Victorian Occultism and the Art of Synesthesia". The Appendix (Austin, TX: The Appendix, LLC) 2 (2): 109–14. https://archive.org/details/TheAppendix-Bodies-2-2. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Carlson, Maria (2015). No Religion Higher Than Truth: A History of the Theosophical Movement in Russia, 1875-1922. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400872794. https://books.google.com/books?id=Jrl9BgAAQBAJ. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- Clute, J. (1997a). "Allen, F M". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=allen_f_m. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Clute, J. (1997b). "Blavatsky, H P". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=blavatsky_h_p. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Clute, J. (1997c). "Meyrink, Gustav". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=meyrink_gustav. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Clute, J. (1997d). "Mundy, Talbot". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=mundy_talbot. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Clute, J. (1997e). "Weird Fiction". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=weird_fiction. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Clute, J. (1999). "Theosophy". in Clute, J.; Nicholls, P.. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (2nd ed.). Orbit. ISBN 9781857238976. http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/theosophy. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Clute, J.; Sterling, B. (1999). "Flammarion, Camille". in Clute, J.; Nicholls, P.. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (2nd ed.). Orbit. ISBN 9781857238976. http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/flammarion_camille. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Ellmann, R. (1964). The identity of Yeats. Galaxy book (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195007121. https://books.google.com/books?id=BqYOAQAAMAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Ellwood, R. S. (2014). Theosophy: A Modern Expression of the Wisdom of the Ages. Quest Books. Wheaton, Ill.: Quest Books. ISBN 9780835631457. https://books.google.com/books?id=bl9bBgAAQBAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Faivre, A. (2010). Western Esotericism: A Concise History. SUNY series in Western Esoteric Traditions. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 9781438433776. https://books.google.com/books?id=MfL-AgAAQBAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- French, B. J. (2000). The Theosophical Masters: An Investigation into the Conceptual Domains of H. P. Blavatsky and C. W. Leadbeater (PhD thesis). Sydney: University of Sydney. hdl:2123/7147.

- Gilhus, I. S.; Mikaelsson, L. (2013). "Theosophy and Popular Fiction". in Hammer, O.; Rothstein, M.. Handbook of the Theosophical Current. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Boston: Brill. pp. 453–72. ISBN 9789004235977. https://books.google.com/books?id=0VozAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA453. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Godwin, J. (1994). The Theosophical Enlightenment. SUNY series in Western esoteric traditions. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791421512. https://books.google.com/books?id=w2PYAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Goldfarb, R. M. (1971). "Madame Blavatsky". The Journal of Popular Culture (Wiley-Blackwell) 5 (3): 660–72. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1971.0503_660.x.

- Hanegraaff, W. J. (2013). "Literature". Western Esotericism: A Guide for the Perplexed. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781441188977. https://books.google.com/books?id=khaNd720XQMC. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Introvigne, M. (2018). Reginald W. Machell (1854–1927): A British Theosophical Artist in San Diego. Torino: UPS. https://www.cesnur.org/2018/machell_san_diego.pdf. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- James, W. (1929). "Lectures XVI And XVII. Mysticism". The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Random House. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/621/621-h/621-h.html#toc23.

- Johnston, C. (2014). "How Count Tolstoy Writes?". in Sekirin, Peter. Americans in Conversation with Tolstoy: Selected Accounts, 1887–1923. McFarland. pp. 55–8. ISBN 9780786481651. https://books.google.com/books?id=kSjBsH-XrCcC. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Kalnitsky, Arnold (2003). "7.5.3 The Voice of the Silence: An Overview of Thematic Contents and Points of Emphasis". The Theosophical Movement of the Nineteenth Century: The Legitimation of the Disputable and the Entrenchment of the Disreputable (D. Litt. et Phil. thesis). Promoter Dr H. C. Steyn. Pretoria: University of South Africa (published 2009). pp. 322–9. hdl:10500/2108. OCLC 1019696826.

- Koeber, R. von (September 1890). Blavatsky, H. P.. ed. "Leo Tolstoi and his Unecclesiastical Christianity". Lucifer (London: Theosophical Publishing Society) 7 (37): 9–14. http://www.iapsop.com/archive/materials/lucifer/lucifer_v7_n37_september_1890.pdf.

- Kuhn, A. B. (1992) [1930]. Theosophy: A Modern Revival of Ancient Wisdom (PhD thesis). American religion series: Studies in religion and culture. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56459-175-3.

- Larson, R. D. (1997). "Anstey, F". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=anstey_f. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- McCready, S. (1997a). "Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna (1831–91)". A William Butler Yeats Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0313283710. https://books.google.com/books?id=6aRxQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- McCready, S. (1997b). "Chatterjee, Mohini (1858–1936)". A William Butler Yeats Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 75–6. ISBN 0313283710. https://books.google.com/books?id=6aRxQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- McCready, S. (1997c). "Johnston, Charles (1867–1931)". A William Butler Yeats Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 205–6. ISBN 0313283710. https://books.google.com/books?id=6aRxQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Monteith, K. (2014). Yeats and Theosophy. Studies in Major Literary Authors. Routledge. ISBN 9781135915629. https://books.google.com/books?id=-064AwAAQBAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Murphet, H. (1975). When Daylight Comes: Biography of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. Theosophical Publishing House. ISBN 9780835604611. https://books.google.com/books?id=T74OAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Ross, D. A. (2014). Critical Companion to William Butler Yeats: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438126920. https://books.google.com/books?id=QxVvh5BHkloC. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Rudbøg, Tim (2012). H. P. Blavatsky's Theosophy in Context (PDF) (PhD thesis). Exeter: University of Exeter. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Sangharakshita, Bhikshu (1958). Paradox and Poetry in The Voice of the Silence. Bangalore: Indian Institute of World Culture. http://www.theosophical.org/files/resources/articles/ParadoxAndPoetry.pdf. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Santucci, J. A. (2012). "Theosophy". in Hammer, O.; Rothstein, M.. The Cambridge Companion to New Religious Movements. Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–46. ISBN 9781107493551. https://books.google.com/books?id=RM0AAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA231. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Sasson, D. (2012). Albanese, C. L.; Stein, S. J.. eds. Yearning for the New Age: Laura Holloway-Langford and Late Victorian Spirituality. Religion in North America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253001771. https://books.google.com/books?id=74jEiVAhVHEC. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Sellon, E. B.; Weber, R. (1992). "Theosophy and The Theosophical Society". in Faivre, A.; Needleman, J.. Modern Esoteric Spirituality. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company. pp. 311–29. ISBN 0-8245-1145-X. https://books.google.com/books?id=UrnXAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Singh, Suman (15 July 2012). "Mohini Mohan Chatterji's Influence on W. B. Yeats". Shodh Sanchayan (Web Portal of Humanity & Social Science Research) 3 (2). ISSN 2249-9180. http://www.shodh.net/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&download=138:4-mohini-mohan-chatterjis-influence-on-wb-yeats-dr-suman-singh-&id=40:vol3-issue-2&Itemid=99. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Stableford, B. M. (1997). "Praed, Mrs". in Clute, J.; Grant, J.. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 9781857233681. http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=praed_mrs. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Steiner, R. (1904). "Theosophy and Tolstoy". Rudolf Steiner Archive & e.Lib. https://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/19041103p01.html.

- Williams, G. M. (1946). Priestess of the Occult: Madame Blavatsky. New York: Alfred A Knopf. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.178230.

- Zirkoff, B. de (1960). "Franz Hartmann". in Zirkoff, B. de. Blavatsky Collected Writings. 8. Wheaton, Ill: Theosophical Publishing House. pp. 439–57. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/theosophy-and-theosophists/de-zirkoff-on-franz-hartmann.pdf. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- In Russian

- Бритиков, А. Ф. (1970). Русский советский научно-фантастический роман. Л.: Наука. https://books.google.com/books?id=GUxGuQEACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Венгерова, З. А.; Соловьёв, В. С. (1892). "Блаватская Елена Петровна" (in ru). Критико-биографический словарь русских писателей и учёных. 3. СПб.: Типо-литография И. А. Ефрона. pp. 301–319. http://www.runivers.ru/bookreader/book16782/#page/331/mode/1up. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Ласько, В. А. (2004). "Книги с полки яснополянской библиотеки" (in ru). Культура и время (Москва: МЦР) (3/4): 232–43. http://www.ivorr.narod.ru/blavatsk/blav_sovrem/100-let/lasko.htm. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Сенкевич, А. Н. (2012) (in ru). Елена Блаватская. Между светом и тьмой. Носители тайных знаний. Москва: Алгоритм. ISBN 978-5-4438-0237-4. OCLC 852503157. https://books.google.com/books?id=KtIwkgEACAAJ. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Толстой, Л. Н. (1956). Полное собрание сочинений: Произведения 1886, 1903–1909 гг. 40. М.: Государственное издательство художественной литературы. http://tolstoy.ru/online/90/40. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Успенский, П. Д. (1911). Tertium Organum. СПб.. http://www.psylib.ukrweb.net/books/uspen01/index.htm. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Шабанова, Ю. А. (2016) (in ru). Теософия: история и современность. Харьков: ФЛП Панов А. Н.. ISBN 978-617-7293-89-6. http://filosof.nmu.org.ua/ua/Шабанова%20Днепр_1_198.pdf. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

External links

|