Physics:Causal structure

In mathematical physics, the causal structure of a Lorentzian manifold describes the causal relationships between points in the manifold.

Introduction

In modern physics (especially general relativity) spacetime is represented by a Lorentzian manifold. The causal relations between points in the manifold are interpreted as describing which events in spacetime can influence which other events.

The causal structure of an arbitrary (possibly curved) Lorentzian manifold is made more complicated by the presence of curvature. Discussions of the causal structure for such manifolds must be phrased in terms of smooth curves joining pairs of points. Conditions on the tangent vectors of the curves then define the causal relationships.

Tangent vectors

If is a Lorentzian manifold (for metric on manifold ) then the nonzero tangent vectors at each point in the manifold can be classified into three disjoint types. A tangent vector is:

- timelike if

- null or lightlike if

- spacelike if

Here we use the metric signature. We say that a tangent vector is non-spacelike if it is null or timelike.

The canonical Lorentzian manifold is Minkowski spacetime, where and is the flat Minkowski metric. The names for the tangent vectors come from the physics of this model. The causal relationships between points in Minkowski spacetime take a particularly simple form because the tangent space is also and hence the tangent vectors may be identified with points in the space. The four-dimensional vector is classified according to the sign of , where is a Cartesian coordinate in 3-dimensional space, is the constant representing the universal speed limit, and is time. The classification of any vector in the space will be the same in all frames of reference that are related by a Lorentz transformation (but not by a general Poincaré transformation because the origin may then be displaced) because of the invariance of the metric.

Time-orientability

At each point in the timelike tangent vectors in the point's tangent space can be divided into two classes. To do this we first define an equivalence relation on pairs of timelike tangent vectors.

If and are two timelike tangent vectors at a point we say that and are equivalent (written ) if .

There are then two equivalence classes which between them contain all timelike tangent vectors at the point. We can (arbitrarily) call one of these equivalence classes future-directed and call the other past-directed. Physically this designation of the two classes of future- and past-directed timelike vectors corresponds to a choice of an arrow of time at the point. The future- and past-directed designations can be extended to null vectors at a point by continuity.

A Lorentzian manifold is time-orientable[1] if a continuous designation of future-directed and past-directed for non-spacelike vectors can be made over the entire manifold.

Curves

A path in is a continuous map where is a nondegenerate interval (i.e., a connected set containing more than one point) in . A smooth path has differentiable an appropriate number of times (typically ), and a regular path has nonvanishing derivative.

A curve in is the image of a path or, more properly, an equivalence class of path-images related by re-parametrisation, i.e. homeomorphisms or diffeomorphisms of . When is time-orientable, the curve is oriented if the parameter change is required to be monotonic.

Smooth regular curves (or paths) in can be classified depending on their tangent vectors. Such a curve is

- chronological (or timelike) if the tangent vector is timelike at all points in the curve. Also called a world line.[2]

- null if the tangent vector is null at all points in the curve.

- spacelike if the tangent vector is spacelike at all points in the curve.

- causal (or non-spacelike) if the tangent vector is timelike or null at all points in the curve.

The requirements of regularity and nondegeneracy of ensure that closed causal curves (such as those consisting of a single point) are not automatically admitted by all spacetimes.

If the manifold is time-orientable then the non-spacelike curves can further be classified depending on their orientation with respect to time.

A chronological, null or causal curve in is

- future-directed if, for every point in the curve, the tangent vector is future-directed.

- past-directed if, for every point in the curve, the tangent vector is past-directed.

These definitions only apply to causal (chronological or null) curves because only timelike or null tangent vectors can be assigned an orientation with respect to time.

- A closed timelike curve is a closed curve which is everywhere future-directed timelike (or everywhere past-directed timelike).

- A closed null curve is a closed curve which is everywhere future-directed null (or everywhere past-directed null).

- The holonomy of the ratio of the rate of change of the affine parameter around a closed null geodesic is the redshift factor.

Causal relations

There are several causal relations between points and in the manifold .

- chronologically precedes (often denoted ) if there exists a future-directed chronological (timelike) curve from to .

- strictly causally precedes (often denoted ) if there exists a future-directed causal (non-spacelike) curve from to .

- causally precedes (often denoted or ) if strictly causally precedes or .

- horismos [3] (often denoted or ) if or there exists a future-directed null curve from to [4] (or equivalently, and ).

These relations satisfy the following properties:

- implies (this follows trivially from the definition)[5]

- , implies [5]

- , implies [5]

- , , are transitive.[5] is not transitive.[6]

- , are reflexive[4]

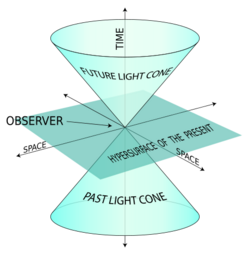

For a point in the manifold we define[5]

- The chronological future of , denoted , as the set of all points in such that chronologically precedes :

- The chronological past of , denoted , as the set of all points in such that chronologically precedes :

We similarly define

- The causal future (also called the absolute future) of , denoted , as the set of all points in such that causally precedes :

- The causal past (also called the absolute past) of , denoted , as the set of all points in such that causally precedes :

- The future null cone of as the set of all points in such that .

- The past null cone of as the set of all points in such that .

- The light cone of as the future and past null cones of together.[7]

- elsewhere as points not in the light cone, causal future, or causal past.[7]

Points contained in , for example, can be reached from by a future-directed timelike curve. The point can be reached, for example, from points contained in by a future-directed non-spacelike curve.

In Minkowski spacetime the set is the interior of the future light cone at . The set is the full future light cone at , including the cone itself.

These sets defined for all in , are collectively called the causal structure of .

For two subsets of we define

- The chronological future of relative to , , is the chronological future of considered as a submanifold of . Note that this is quite a different concept from which gives the set of points in which can be reached by future-directed timelike curves starting from . In the first case the curves must lie in in the second case they do not. See Hawking and Ellis.

- The causal future of relative to , , is the causal future of considered as a submanifold of . Note that this is quite a different concept from which gives the set of points in which can be reached by future-directed causal curves starting from . In the first case the curves must lie in in the second case they do not. See Hawking and Ellis.

- A future set is a set closed under chronological future.

- A past set is a set closed under chronological past.

- An indecomposable past set (IP) is a past set which isn't the union of two different open past proper subsets.

- An IP which does not coincide with the past of any point in is called a terminal indecomposable past set (TIP).

- A proper indecomposable past set (PIP) is an IP which isn't a TIP. is a proper indecomposable past set (PIP).

- The future Cauchy development of , is the set of all points for which every past directed inextendible causal curve through intersects at least once. Similarly for the past Cauchy development. The Cauchy development is the union of the future and past Cauchy developments. Cauchy developments are important for the study of determinism.

- A subset is achronal if there do not exist such that , or equivalently, if is disjoint from .

thumb|Causal diamond

- A Cauchy surface is a closed achronal set whose Cauchy development is .

- A metric is globally hyperbolic if it can be foliated by Cauchy surfaces.

- The chronology violating set is the set of points through which closed timelike curves pass.

- The causality violating set is the set of points through which closed causal curves pass.

- The boundary of the causality violating set is a Cauchy horizon. If the Cauchy horizon is generated by closed null geodesics, then there's a redshift factor associated with each of them.

- For a causal curve , the causal diamond is (here we are using the looser definition of 'curve' whereon it is just a set of points), being the point in the causal past of . In words: the causal diamond of a particle's world-line is the set of all events that lie in both the past of some point in and the future of some point in . In the discrete version, the causal diamond is the set of all the causal paths that connect from .

Properties

See Penrose (1972), p13.

- A point is in if and only if is in .

- The horismos is generated by null geodesic congruences.

Topological properties:

- is open for all points in .

- is open for all subsets .

- for all subsets . Here is the closure of a subset .

Conformal geometry

Two metrics and are conformally related[8] if for some real function called the conformal factor. (See conformal map).

Looking at the definitions of which tangent vectors are timelike, null and spacelike we see they remain unchanged if we use or . As an example suppose is a timelike tangent vector with respect to the metric. This means that . We then have that so is a timelike tangent vector with respect to the too.

It follows from this that the causal structure of a Lorentzian manifold is unaffected by a conformal transformation.

A null geodesic remains a null geodesic under a conformal rescaling.

Conformal infinity

An infinite metric admits geodesics of infinite length/proper time. However, we can sometimes make a conformal rescaling of the metric with a conformal factor which falls off sufficiently fast to 0 as we approach infinity to get the conformal boundary of the manifold. The topological structure of the conformal boundary depends upon the causal structure.

- Future-directed timelike geodesics end up on , the future timelike infinity.

- Past-directed timelike geodesics end up on , the past timelike infinity.

- Future-directed null geodesics end up on ℐ+, the future null infinity.

- Past-directed null geodesics end up on ℐ−, the past null infinity.

- Spacelike geodesics end up on spacelike infinity.

In various spaces:

- Minkowski space: are points, ℐ± are null sheets, and spacelike infinity has codimension 2.

- Anti-de Sitter space: there's no timelike or null infinity, and spacelike infinity has codimension 1.

- de Sitter space: the future and past timelike infinity has codimension 1.

Gravitational singularity

If a geodesic terminates after a finite affine parameter, and it is not possible to extend the manifold to extend the geodesic, then we have a singularity.

- For black holes, the future timelike boundary ends on a singularity in some places.

- For the Big Bang, the past timelike boundary is also a singularity.

The absolute event horizon is the past null cone of the future timelike infinity. It is generated by null geodesics which obey the Raychaudhuri optical equation.

See also

- Causal dynamical triangulation (CDT)

- Causality conditions

- Causal sets

- Cauchy surface

- Closed timelike curve

- Cosmic censorship hypothesis

- Globally hyperbolic manifold

- Malament–Hogarth spacetime

- Null infinity

- Penrose diagram

- Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems

- Spacetime

Notes

- ↑ Hawking & Israel 1979, p. 255

- ↑ Galloway, Gregory J.. "Notes on Lorentzian causality". University of Miami. p. 4. https://www.math.miami.edu/~galloway/vienna-course-notes.pdf.

- ↑ Penrose 1972, p. 15

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Papadopoulos, Kyriakos; Acharjee, Santanu; Papadopoulos, Basil K. (May 2018). "The order on the light cone and its induced topology". International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics 15 (5): 1850069–1851572. doi:10.1142/S021988781850069X. Bibcode: 2018IJGMM..1550069P.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Penrose 1972, p. 12

- ↑ Stoica, O. C. (25 May 2016). "Spacetime Causal Structure and Dimension from Horismotic Relation". Journal of Gravity 2016: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2016/6151726.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sard 1970, p. 78

- ↑ Hawking & Ellis 1973, p. 42

References

- Hawking, S.W.; Ellis, G.F.R. (1973), The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-20016-4

- Hawking, S.W.; Israel, W. (1979), General Relativity, an Einstein Centenary Survey, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22285-0

- Penrose, R. (1972), Techniques of Differential Topology in Relativity, SIAM, ISBN 0898710057

- Sard, R. D. (1970). Relativistic Mechanics - Special Relativity and Classical Particle Dynamics. New York: W. A. Benjamin. ISBN 978-0805384918. https://archive.org/details/relativisticmech0000sard.

Further reading

- G. W. Gibbons, S. N. Solodukhin; The Geometry of Small Causal Diamonds arXiv:hep-th/0703098 (Causal intervals)

- S.W. Hawking, A.R. King, P.J. McCarthy; A new topology for curved space–time which incorporates the causal, differential, and conformal structures; J. Math. Phys. 17 2:174-181 (1976); (Geometry, Causal Structure)

- A.V. Levichev; Prescribing the conformal geometry of a lorentz manifold by means of its causal structure; Soviet Math. Dokl. 35:452-455, (1987); (Geometry, Causal Structure)

- D. Malament; The class of continuous timelike curves determines the topology of spacetime; J. Math. Phys. 18 7:1399-1404 (1977); (Geometry, Causal Structure)

- A.A. Robb; A theory of time and space; Cambridge University Press, 1914; (Geometry, Causal Structure)

- A.A. Robb; The absolute relations of time and space; Cambridge University Press, 1921; (Geometry, Causal Structure)

- A.A. Robb; Geometry of Time and Space; Cambridge University Press, 1936; (Geometry, Causal Structure)

- R.D. Sorkin, E. Woolgar; A Causal Order for Spacetimes with C^0 Lorentzian Metrics: Proof of Compactness of the Space of Causal Curves; Classical & Quantum Gravity 13: 1971-1994 (1996); arXiv:gr-qc/9508018 (Causal Structure)

External links

- Turing Machine Causal Networks by Enrique Zeleny, the Wolfram Demonstrations Project

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Causal Network". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CausalNetwork.html.

|