Physics:Gamow factor

The Gamow factor, Sommerfeld factor or Gamow–Sommerfeld factor,[1] named after physicists George Gamow and Arnold Sommerfeld, is a probability factor for two nuclear particles' chance of overcoming the Coulomb barrier in order to undergo nuclear reactions, for example in nuclear fusion. By classical physics, there is almost no possibility for protons to fuse by crossing each other's Coulomb barrier at temperatures commonly observed to cause fusion, such as those found in the Sun. In 1927 it was discovered that there is a significant chance for nuclear fusion due to quantum tunnelling.

While the probability of overcoming the Coulomb barrier increases rapidly with increasing particle energy, for a given temperature, the probability of a particle having such an energy falls off very fast, as described by the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution. Gamow found that, taken together, these effects mean that for any given temperature, the particles that fuse are mostly in a temperature-dependent narrow range of energies known as the Gamow window. The maximum of the distribution is called the Gamow peak.

Description

When two positively charged nuclei approach each other, they are repulsed by the strong electric field between them – the Coulomb barrier. In order to undergo a nuclear reaction, the nuclei must quantum-tunnel through the barrier. The probability of this happening is proportional to the following factor:[2]

where is the Gamow energy

where is the reduced mass of the two particles.[lower-alpha 1] The constant is the fine-structure constant, is the speed of light, and and are the respective atomic numbers of each particle.

It is sometimes rewritten using the Sommerfeld parameter η, such that

where η is a dimensionless quantity used in nuclear astrophysics in the calculation of reaction rates between two nuclei. It is defined as[3][4]

where e is the elementary charge, v is the magnitude of the relative incident velocity in the centre-of-mass frame.[lower-alpha 2]

S-factor

The probability of a nuclear reaction is proportional to the probability that the particles penetrate the barrier , times the probability that they react upon doing so. The latter probability is described by the astrophysical S-factor.

The S-factor depends on the complicated strong force interactions between the nuclei, and thus nonlinearly depends on particle energy. It is defined as[5]

- ,

where σ is the cross section, a measure of the total reaction probability.

The Coulomb barrier causes the cross section to have a strong exponential dependence on . The S-factor remedies this by factoring out the Coulomb component of the cross section (the Gamow factor) and the DeBroglie wavelength (the cross section is proportional to the wavelength squared, which is proportional to ). For nuclear reactions without resonances, varies less with than does. Thus, is a useful reparameterization of .[6]

Gamow peak

For an ideal gas, the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution is proportional to

where is the average squared speed of all particles, is the Boltzmann constant and T is absolute temperature.

The fusion probability is the product of the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution factor and the Gamow factor

The maximum of the fusion probability is given by which yields[7]

This quantity is known as the Gamow peak.[lower-alpha 3]

Expanding around gives:[7]

where (in joule)

is the Gamow window.[lower-alpha 4]

Derivation

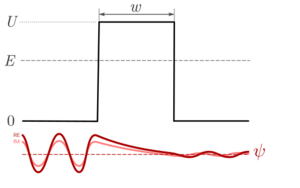

1D problem

The derivation consists in the one-dimensional case of quantum tunnelling using the WKB approximation.[8] Considering a wave function of a particle of mass m, we take area 1 to be where a wave is emitted, area 2 the potential barrier which has height V and width l (at ), and area 3 its other side, where the wave is arriving, partly transmitted and partly reflected. For wave numbers k [m−1] and energy E we get:

where and both in [1/m]. This is solved for given A and phase α by taking the boundary conditions at the barrier edges, at and : there and its derivatives must be equal on both sides. For , this is easily solved by ignoring the time exponential and considering the real part alone (the imaginary part has the same behaviour). We get, up to factors

- depending on the β phases which are typically of order 1, and

- of the order of (assumed not very large, since V is greater than E (not marginally)):

and

Next, the alpha decay can be modelled as a symmetric one-dimensional problem, with a standing wave between two symmetric potential barriers at and , and emitting waves at both outer sides of the barriers. Solving this can in principle be done by taking the solution of the first problem, translating it by and gluing it to an identical solution reflected around .

Due to the symmetry of the problem, the emitting waves on both sides must have equal amplitudes (A), but their phases (α) may be different. This gives a single extra parameter; however, gluing the two solutions at requires two boundary conditions (for both the wave function and its derivative), so in general there is no solution. In particular, re-writing (after translation by ) as a sum of a cosine and a sine of , each having a different factor that depends on k and β; the factor of the sine must vanish, so that the solution can be glued symmetrically to its reflection. Since the factor is in general complex (hence its vanishing imposes two constraints, representing the two boundary conditions), this can in general be solved by adding an imaginary part of k, which gives the extra parameter needed. Thus E will have an imaginary part as well.

The physical meaning of this is that the standing wave in the middle decays; the waves newly emitted have therefore smaller amplitudes, so that their amplitude decays in time but grows with distance. The decay constant, denoted λ [1/s], is assumed small compared to .

λ can be estimated without solving explicitly, by noting its effect on the probability current conservation law. Since the probability flows from the middle to the sides, we have:

note the factor of 2 is due to having two emitted waves.

Taking , this gives:

Since the quadratic dependence on is negligible relative to its exponential dependence, we may write:

Remembering the imaginary part added to k is much smaller than the real part, we may now neglect it and get:

Note that is the particle velocity, so the first factor is the classical rate by which the particle trapped between the barriers ( apart) hits them.

3D problem

Finally, moving to the three-dimensional problem, the spherically symmetric Schrödinger equation reads (expanding the wave function in spherical harmonics and looking at the l-th term):

Since amounts to enlarging the potential, and therefore substantially reducing the decay rate (given its exponential dependence on ): we focus on , and get a very similar problem to the previous one with , except that now the potential as a function of r is not a step function. In short

The main effect of this on the amplitudes is that we must replace the argument in the exponent, taking an integral of over the distance where rather than multiplying by width l. We take the Coulomb potential:

where is the vacuum electric permittivity, e the electron charge, z = 2 is the charge number of the alpha particle and Z the charge number of the nucleus (Z–z after emitting the particle). The integration limits are then:

where we assume the nuclear potential energy is still relatively small, and

, which is where the nuclear negative potential energy is large enough so that the overall potential is smaller than E.

Thus, the argument of the exponent in λ is:

This can be solved by substituting and then and solving for θ, giving:

where . Since x is small, the x-dependent factor is of the order 1.

Assuming

, the x-dependent factor can be replaced by

giving:

with

Which is the same as the formula given in the beginning of the article with

,

and the fine-structure constant

For a radium alpha decay, Z = 88, z = 2 and m ≈ 4mp, EG is approximately 50 GeV. Gamow calculated the slope of with respect to E at an energy of 5 MeV to be ~ 1014 J−1, compared to the experimental value of 0.7×1014 J−1.[lower-alpha 5]

History

In 1927, Ernest Rutherford published an article in Philosophical Magazine on a problem related to Hans Geiger's 1921 experiment of scattering alpha particles from uranium.[9] Previous experiments with thorium C' (now called polonium-262)[lower-alpha 6] confirmed that uranium has a Coulomb barrier of 8.57 MeV, however uranium emitted alpha particles of 4.2 MeV.[9] The emitted energy was too low to overcome the barrier. On 29 July 1928, George Gamow, and independently the next day Ronald Wilfred Gurney and Edward Condon submitted their solution based on quantum tunnelling to the journal Zeitschrift für Physik.[9] Their work was based on previous work on tunnelling by J. Robert Oppenheimer, Gregor Wentzel, Lothar Wolfgang Nordheim, and Ralph H. Fowler.[9] Gurney and Condon cited also Friedrich Hund.[9]

In 1931, Arnold Sommerfeld introduced a similar factor (a Gaunt factor) for the discussion of bremsstrahlung.[10]

Gamow popularized his personal version of the discovery in his 1970's book, My World Line: An Informal Autobiography.[9]

Examples

The Gamow energies for some common nuclear fusion reactions are given in kiloelectronvolts below, as well as the low-energy limits of the astrophysical S-factors in kiloelectronvolt–barns.[6]

| Reaction | (keV) | (keV1/2) | (keV⋅barn) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D + T → α + n | 1180 | 34.4 | 12000 |

| D + D → T + p | 986 | 31.4 | 56 |

| D + D → 3He + n | 986 | 31.4 | 54 |

| D + 3He → α + p | 4730 | 68.8 | 5900 |

| p + 11B → α + α + α | 22600 | 150.3 | 2×105 |

| p + p → D + e+ + ν | 493 | 22.2 | 4.0×10−22 |

| p + D → 3He + Template:Gamma | 657 | 25.6 | 2.5×10−4 |

| 3He + 3He → α + p + p | 23700 | 153.8 | 5400 |

| p + 12C → 13N + Template:Gamma | 32800 | 181.0 | 1.34 |

| p + 13C → 14N + Template:Gamma | 32900 | 181.5 | 7.6 |

| p + 14N → 15O + Template:Gamma | 45100 | 212.3 | 3.5 |

| p + 15N → 12C + α | 45300 | 212.8 | 67500 |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Identical (protons, 2He2+): cation vs 1H1+

- ↑

- ↑ At kT resp. EG the factors are 1/e (37%) at any temperature. Locus E0 of the Gamow peak is

- ↑ Double log. graphs vs T: . Similar

- ↑ ; (Natural log.) Around 10 /MeV; 'kT = 0.217 fJ = 0.135 keV', 'typical core temperatures in main-sequence stars (the Sun) give kT of the order of 1 keV': joule

- ↑ 88Ra (90Th) 92U are radioactive elements in periods 7, 84Po in period 6. Spontaneous nuclear fission

References

- ↑ Yoon, Jin-Hee; Wong, Cheuk-Yin (February 9, 2008). "Relativistic Modification of the Gamow Factor". Physical Review C 61 (4). doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.61.044905. Bibcode: 2000PhRvC..61d4905Y.

- ↑ "Nuclear reactions in stars". Dept. Physics & Astronomy University College London. https://zuserver2.star.ucl.ac.uk/~idh/PHAS2112/Lectures/Current/Part7.pdf.

- ↑ Rolfs, C.E.; Rodney, W.S. (1988). Cauldrons in the Cosmos. Chicago: University of Chicago press. p. 156. ISBN 0-226-72456-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=BHKLFPUS1RcC&pg=PA156.

- ↑ Breit, G. (1967). "Virtual Coulomb Excitation in Nucleon Transfer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 57 (4): 849–855. doi:10.1073/pnas.57.4.849. PMID 16591541. PMC 224623. Bibcode: 1967PNAS...57..849B. http://www.pnas.org/content/57/4/849.full.pdf. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Thompson, Ian J.; Nunes, Filomena M. (2009). Nuclear Reactions for Astrophysics: Principles, Calculations and Applications of Low-Energy Reactions.. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-85635-5.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Atzeni, Stefano; Meyer-ter-Vehn, Jürgen (2004). The physics of inertial fusion: Beam plasma interaction, hydrodynamics, hot dense matter. New York: Clarendon Press. pp. 3–14. ISBN 0198562640.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Clayton, D. D. (Donald Delbert) (1983). Principles of stellar evolution and nucleosynthesis: with a new preface. Internet Archive. Chicago ; London : University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10952-7. https://archive.org/details/principlesofstel0000clay/mode/2up.

- ↑ Quantum Theory of the Atomic Nucleus, G. Gamow. Translated to English from: G. Gamow, ZP, 51, 204

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Merzbacher, Eugen (2002-08-01). "The Early History of Quantum Tunneling". Physics Today 55 (8): 44–49. doi:10.1063/1.1510281. ISSN 0031-9228. Bibcode: 2002PhT....55h..44M. https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/article-abstract/55/8/44/412308/The-Early-History-of-Quantum-Tunneling-Molecular?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

- ↑ Iben, Icko (2013) (in en). Stellar Evolution Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01656-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=hFmpIXwLUvIC&dq=sommerfeld++1931+factor&pg=PA335.

External links

- Modeling Alpha Half-life (Georgia State University) hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu

|