Physics:Luttinger–Ward functional

In solid state physics, the Luttinger–Ward functional,[1] proposed by Joaquin Mazdak Luttinger and John Clive Ward in 1960,[2] is a scalar functional of the bare electron-electron interaction and the renormalized one-particle propagator. In terms of Feynman diagrams, the Luttinger–Ward functional is the sum of all closed, bold, two-particle irreducible diagrams, i.e., all diagrams without particles going in or out that do not fall apart if one removes two propagator lines. It is usually written as [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi[G] }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi[G,U] }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] is the one-particle Green's function and [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] is the bare interaction. The Luttinger–Ward functional has no direct physical meaning, but it is useful in proving conservation laws.

The functional is closely related to the Baym–Kadanoff functional constructed independently by Gordon Baym and Leo Kadanoff in 1961.[3] Some authors use the terms interchangeably;[4] if a distinction is made, then the Baym–Kadanoff functional is identical to the two-particle irreducible effective action [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma[G] }[/math], which differs from the Luttinger–Ward functional by a trivial term.

Construction

Given a system characterized by the action [math]\displaystyle{ S[c, \bar c] }[/math] in terms of Grassmann fields [math]\displaystyle{ c_i, \bar c_i }[/math], the partition function can be expressed as the path integral:

- [math]\displaystyle{ Z[J] = \int \mathrm D[c,\bar c] \exp\!\Big(-S[c, \bar c] + \sum_{ij} \bar c_i J_{ij} c_j\Big) }[/math],

where [math]\displaystyle{ J }[/math] is a binary source field. By expansion in the Dyson series, one finds that [math]\displaystyle{ Z = Z[J=0] }[/math] is the sum of all (possibly disconnected), closed Feynman diagrams. [math]\displaystyle{ Z[J] }[/math] in turn is the generating functional of the N-particle Green's function:

- [math]\displaystyle{ G_{i_1j_1\ldots i_Nj_N} = - \langle c_{i_1} \bar c_{j_1} \cdots c_{i_N} \bar c_{j_N} \rangle = \frac {-1}{Z[0]} \left. \frac {\delta^N Z[J]} {\delta J_{j_1i_1}\cdots \delta J_{j_Ni_N} } \right|_{J=0} }[/math]

The linked-cluster theorem asserts that the effective action [math]\displaystyle{ W =- \log Z }[/math] is the sum of all closed, connected, bare diagrams. [math]\displaystyle{ W[J] = -\log Z[J] }[/math] in turn is the generating functional for the connected Green's function. As an example, the two particle connected Green's function reads:

- [math]\displaystyle{ G^\mathrm{conn}_{ijkl} = - \langle c_i \bar c_j c_k \bar c_l \rangle + \langle c_i \bar c_j \rangle \langle c_k \bar c_l \rangle - \langle c_i \bar c_l \rangle \langle c_k \bar c_j \rangle = \left. \frac {\delta^2 W[J]} {\delta J_{ji}\delta J_{lk} } \right|_{J=0} }[/math]

To pass to the two-particle irreducible (2PI) effective action, one performs a Legendre transform of [math]\displaystyle{ W[J] }[/math] to a new binary source field. One chooses an, at this point arbitrary, convex [math]\displaystyle{ G_{ij} }[/math] as the source and obtains the 2PI functional, also known as Baym–Kadanoff functional:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma[G] = \Big[ W[J] - \sum_{ij} J_{ij} G_{ij} \Big]_{J=J[G]} }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ G_{ij} = -\frac {\delta W[J]}{\delta J_{ij}} }[/math].

Unlike the connected case, one more step is required to obtain a generating functional from the two-particle irreducible effective action [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma }[/math] because of the presence of a non-interacting part. By subtracting it, one obtains the Luttinger–Ward functional:[5]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi[G] = \Gamma[G] - \Gamma_0[G] = \Gamma[G] - \mathrm{tr}\log(-G) - \mathrm{tr}(\Sigma G) }[/math],

where [math]\displaystyle{ \Sigma }[/math] is the self-energy. Along the lines of the proof of the linked-cluster theorem, one can show that this is the generating functional for the two-particle irreducible propagators.

Properties

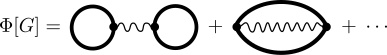

Diagrammatically, the Luttinger–Ward functional is the sum of all closed, bold, two-particle irreducible Feynman diagrams (also known as “skeleton” diagrams):

The diagrams are closed as they do not have any external legs, i.e., no particles going in or out of the diagram. They are “bold” because they are formulated in terms of the interacting or bold propagator rather than the non-interacting one. They are two-particle irreducible since they do not become disconnected if we sever up to two fermionic lines.

The Luttinger–Ward functional is related to the grand potential [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] of a system:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega = \mathrm{tr}\log(-G) + \mathrm{tr}(\Sigma G) + \Phi\left[G\right] }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \Phi }[/math] is a generating functional for irreducible vertex quantities: the first functional derivative with respect to [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] gives the self-energy, while the second derivative gives the partially two-particle irreducible four-point vertex:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Sigma_{ij} = \frac {\delta\Phi} {\delta G_{ij}} }[/math]; [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_{ijkl} = \frac {\delta^2\Phi} {\delta G_{ij}\delta G_{kl}} }[/math]

While the Luttinger–Ward functional exists, it can be shown to be not unique for Hubbard-like models.[6] In particular, the irreducible vertex functions show a set of divergencies, which causes the self-energy to bifurcate into a physical and an unphysical solution.[7]

Baym and Kadanoff showed that we can satisfy the conservation law for any functional [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi\left[G\right] }[/math], thanks to the Noether's theorem. This is followed by the fact that the equation of motion of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] responding to one-body external fields apparently satisfies the space- and time- translational symmetries as well as the abelian gauge symmetry (phase symmetry), as long as the equation of motion is given with the derivative of [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi\left[G\right] }[/math].[3] Note that reverse is also true. Based on the diagramatic analysis, what Baym found is that [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\delta \Sigma(1,\left[G\right])}{\delta G(2)}=\frac{\delta \Sigma(2,\left[G\right])}{\delta G(1)} }[/math] is needed to satisfy the conservation law. This is nothing but the completely-integrable condition, implying the existence of [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi\left[G\right] }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \Sigma\left[G\right]=\frac{\delta \Phi\left[G\right]}{\delta G} }[/math] (recall the completely-integrable condition for [math]\displaystyle{ df= A(x,y)dx +B(x,y)dy }[/math]).

Thus the remainig problem is how to determine [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi\left[G\right] }[/math] approximately. Such approximations are called as conserving approximation. Some examples:

- The (fully self-consistent) GW approximation is equivalent to truncating [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi }[/math] to so-called ring diagrams: [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi[G]\approx GUG + GUGGUG + \ldots }[/math] (A ring diagram consists of polarisation bubbles connected by interaction lines).

- Dynamical mean field theory is equivalent to taking only purely local diagrams into account: [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi[G_{ij},U_{ijkl}] }[/math][math]\displaystyle{ \approx \Phi[G_{ii}, U_{iiii}] }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ i,j,k,l }[/math] are lattice site indices.[4]

See also

- Luttinger's theorem

- Ward identity

References

- ↑ Potthoff, M. (2003). "Self-energy-functional approach to systems of correlated electrons". European Physical Journal B 32 (4): 429–436. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2003-00121-8. Bibcode: 2003EPJB...32..429P.

- ↑ Luttinger, J. M.; Ward, J. C. (1960). "Ground-State Energy of a Many-Fermion System. II". Physical Review 118 (5): 1417–1427. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.118.1417. Bibcode: 1960PhRv..118.1417L.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Baym, G.; Kadanoff, L. P. (1961). "Conservation Laws and Correlation Functions". Physical Review 124 (2): 287–299. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.124.287. Bibcode: 1961PhRv..124..287B.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kotliar, G.; Savrasov, S. Y.; Haule, K.; Oudovenko, V. S.; Parcollet, O.; Marianetti, C. A. (2006). "Electronic structure calculations with dynamical mean-field theory". Rev. Mod. Phys. 78 (3): 865–951. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.78.865. Bibcode: 2006RvMP...78..865K.

- ↑ Rentrop, J. F.; Meden, V.; Jakobs, S. G. (2016). "Renormalization group flow of the Luttinger–Ward functional: Conserving approximations and application to the Anderson impurity model". Phys. Rev. B 93 (19): 195160. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.93.195160. Bibcode: 2016PhRvB..93s5160R.

- ↑ Kozik, E.; Ferrero, M.; Georges, A. (2015). "Nonexistence of the Luttinger-Ward Functional and Misleading Convergence of Skeleton Diagrammatic Series for Hubbard-Like Models". Phys. Rev. Lett. 114 (15): 156402. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.156402. PMID 25933324. Bibcode: 2015PhRvL.114o6402K.

- ↑ Schaefer, T.; Rohringer, G.; Gunnarsson, O.; Ciuchi, S.; Sangiovanni, G.; Toschi, A. (2013). "Divergent Precursors of the Mott-Hubbard Transition at the Two-Particle Level". Phys. Rev. Lett. 110 (24): 246405. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.246405. PMID 25165946. Bibcode: 2013PhRvL.110x6405S.

|