Physics:PET bottle recycling

- Sorting at a material recovery facility

- Bales of colour-sorted PET bottles

- A reprocessing facility where used bottles are converted into clean flakes or pellets suitable for remoulding into new items

- Recycled PET flakes

- A water bottle made from recycled PET (bottle-to-bottle recycling)

- A polyester bag made from recycled PET

- A food tray made from recycled PET bearing the rPET symbol

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is one of the most common polymers in its polyester family. Its global market size was estimated to be worth 37.25 billion USD in 2021.[1] Polyethylene terephthalate is used in several applications such as; textile fibres, bottles, rigid/flexible packaging, and electronics. However, it accounts for 12% in global solid waste.[2] This is why bottle recycling is highly encouraged and has reached its highest level in decades (33% in 2023). In 2023, the US collected 1,962 million pounds of bottles for recycling.[3] Compared to glass bottles, the PET bottle is lightweight and has a lower carbon footprint in production and transportation. Recycling further reduces emissions. The recycled material can be put back into bottles, fibres, film, thermoformed packaging and strapping.[4]

After collecting the bottles from landfills, they are sorted, cleaned and grinded. This grinded material is "bottle flake", which is then processed by either:

- "Basic" or "physical" recycling. Bottle flake is melted into its new shape directly with basic changes in its physical properties.[5]

- "Chemical" or "advanced" recycle. Bottle flake is partially or totally depolymerized then enabling purification. The resulting oligomers or monomers are repolymerized to PET polymer, which is then processed in the same way as virgin polymer.

In either case, the resulting feedstock is known as "r-PET" or "rPET" ("recycled PET").[5] This recycled PET's carbon footprint is 79% lower than virgin PET's, namely 0.45kg CO2 per kg instead of 2.5kg C02 per kg.[6]

Bottle manufacturing

PET and rPET are both used in the creation of bottled water (still and carbonated). Bottled water companies have been voluntarily using rPET in the production and many companies are producing bottles using 100% rPET nowadays. Such companies include Dasani, Fiji and Nestlé Pure Life. Other goods bottled in PET include oil, vinegar, milk, and shampoo. These bottles are closed with polyolefin screw closure with antitamper ring, and have a label which may be printed on paper or plastic and may be glued on. The resin may be colourless or tinted blue, green or brown, or pigmented white.[7] [8]

When manufacturing these water bottles, the energy used to mold the resin into its shape varies based on the bottle shape and its thickness. Some bottles have complex shapes such as Dasani while other bottles have a very simple form such as Smartwater. Therefore, the energy used to create these bottles can range from 8.33 - 20 MJ/kg where the units "MJ" represent megajoules,[9][10] a unit for energy. The emissions associated with the production range from 0.034 – 0.046 kg C02-eq per 500mL.[9]

Collection and sorting

The empty PET packaging is discarded by the consumer after its use and becomes PET waste. In the recycling industry, this is referred to as "post-consumer PET". All types of PET packaging, including bottles are usually marked with the recycle symbol 1. The bottles are sent to trash centers (materials recovery facilities) and get sorted out from the other disposable items. There are times when the recyclables are taken to a transfer station first. At this facility, the materials are stored, sorted, and compacted before being transported to a true recycling facility where they are further processed. This step is especially common in areas where MRFs are located far from collection points Here the PET bottles are sorted and separated from other objects and bottles made of other materials

Collection and sorting process in Switzerland

Source:[5]

- recyclables collected from bins and sent to facility

- metal collection

- ballistic sorting (items that fall slower or faster in air such as dust, films, glass bottles and stones are removed here)

- metal separation again

- spectral sorting: sensors detect polymer type and colour

- sorting on a conveyor belt (manual)

- baling: the flattened bottles are compressed into bales for shipment to the processing centre

Types of sorting at MRFs

- Air classifiers: Stream of air directed towards conveyor belt that lifts away lighter materials (paper and light plastics)

- Eddy current / magnetic separators: Use magnets to separate magnetized and non-magnetized metals

- Manual separation: Workers stationed along conveyor belt that sort out items and contaminants (usually assisting the machines and catching what they missed)

- Optical sorters: A camera or laser sorts items based on color, shape, and other properties (still a new technology)

- Screens: Rotating screens that separate materials based on size (like a colander)

|

|

The sorted post-consumer PET bottless are flattened, pressed into bales and offered for sale to recycling companies. Colourless/light blue post-consumer PET attract higher sales prices than the darker blue and green fractions. The mixed color fraction is the least valuable due simply to the fact unlike aluminium, there are few standards when it comes to the coloration of PET. Unlike clear varieties, PET with unique color characteristics are only useful to the particular manufacturer that uses that color.[12] For material recovery facilities, colored PET bottles are therefore a cause for concern as they can impact the financial viability of recycling such materials. The Plastics Recyclers Europe (PRE, Brussels, Belgium), that an upsurge in a variety of PET colors would be a problem because no market exists for them in the current recycling climate.[13] From there, there are two types of recycling; chemical or mechanical.

Types of collections

- Deposit: some countries have legislated a deposit for packaging including PET bottles. In the EU, deposit schemes average an 86% recovery rate.[14]

- Collect: waste collectors pick up PET bottles mixed into some other stream (54% recovery in EU).

- Bring: consumers take PET bottles and place them into a container (43% recovery in EU).

Different countries have opted for different systems.

- France: public voluntarily puts PET bottles into containers for plastic bottles and metal packaging. The stream in which PET bottles are collected comprises metallic packaging, plastic bottles, and unwanted contaminants.

- Germany: PET bottles carry a deposit,[15] so PET bottles are collected by retailers. The collected stream consists almost entirely of PET bottles.

- Singapore: plastic bottles are collected with glass bottles. The stream in which PET bottles are collected comprises PET bottles, other plastic bottles and glass bottles, and contamination.

- Switzerland: Retailers contribute a fee to a national operator (PRS) who manages collection bins, sorting and production of rPET flake. The stream in which PET bottles are collected is intended to be PET bottles, but contains other PET packaging and other contamination.[5]

- UK: Plastic producers pay a fee, and collection is devolved to municipalities.[16] The stream in which PET bottles are collected varies by municipality, but always require further sorting.

- United States: curbside recycling to which most consumers have access. The waste hauler brings the recycled material to a material recovery facilities (MRFs) where it is further separated. The PET is then baled and sent on to a PET reclaimer. The PET reclaimer processes the bale, grinding the PET into flakes. Some do additional processing to make ready for food grade packaging.

Chemical recycling

This method of recycling is not very common anymore since it is a more intensive and expensive process. Chemical recycling involves breaking down the plastic into its monomers which can be used as building blocks for new materials. Because of the use of more energy for the chemical reactions to take place, chemical recycling produces more emissions than mechanical recycling.[17] This process is also known as "Tertiary" or "Advanced" recycling. Polyethylene terephthalate can be depolymerized partially or completely to yield the constituent oligomers or the monomers, MEG and PTA or DMT. The main processes are glycolysis, methanolysis or hydrolysis.[18][19] After purification, the oligomers or monomers can be used to prepare new recycled polyethylene terephthalate ("r-PET"). The ester bonds in polyethylene terephthalate may be cleaved by hydrolysis, or by transesterification. The reactions are simply the reverse of those used in production.[20]

Partial glycolysis

The task consists in feeding 10–25% bottle flakes while maintaining the quality of the bottle pellets that are manufactured on the line. This aim is solved by degrading the PET bottle flakes—already during their first plasticization, which can be carried out in a single- or multi-screw extruder—to an intrinsic viscosity of about 0.30 dℓ/g by adding small quantities of ethylene glycol and by subjecting the low-viscosity melt stream to an efficient filtration directly after plasticization. Furthermore, temperature is brought to the lowest possible limit. In addition, with this way of processing, the possibility of a chemical decomposition of the hydro peroxides is possible by adding a corresponding P-stabilizer directly when plasticizing. The destruction of the hydro peroxide groups is, with other processes, already carried out during the last step of flake treatment for instance by adding H3PO3.[21] The partially glycolyzed and finely filtered recycled material is continuously fed to the esterification or prepolycondensation reactor, the dosing quantities of the raw materials are being adjusted accordingly.

Total glycolysis

The treatment of polyester waste through total glycolysis to fully convert the polyester to bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (C6H4(CO2CH2CH2OH)2). This compound is purified by vacuum distillation, and is one of the intermediates used in polyester manufacture (see production). The reaction involved is as follows:[19]

- [(CO)C6H4(CO2CH2CH2O)]n + n HOCH2CH2OH → n C6H4(CO2CH2CH2OH)2

Methanolysis

converts the polyester to dimethyl terephthalate(DMT), which can be filtered and vacuum distilled:[19]

- [(CO)C6H4(CO2CH2CH2O)]n + 2n CH3OH → n C6H4(CO2CH3)2

Even though polyester production based on dimethyl terephthalate(DMT) is limited to legacy plants,[22] investments were announced in 2021 and 2022 into methanolysis plants.[23][24]

Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis can be done in a neutral, alkaline or acidic environment.[19][25]

Neutral hydrolysis

Polyethylene terephthalate can be hydrolyzed to terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol under high temperature (200-300 °C) and pressure. The resultant crude terephthalic acid can be purified by recrystallization to yield material suitable for re-polymerization:

- [(CO)C6H4(CO2CH2CH2O)]n + 2n H2O → n C6H4(CO2H)2 + n HOCH2CH2OH

Avoiding a neutralization step consumes less resource than alkaline or acidic hydrolysis, but there is no opportunity to filter a solution, so mechanical impurities remain with the terephthalic acid.[19] This method does not appear to have been commercialized as of 2022.

Alkaline hydrolysis

Alkaline hydrolysis is done in an aqueous solution of potassium hydroxide or sodium hydroxide. The reaction yields ethylene glycol and the terephalate salt, in aqueous solution. After separation and filtration, in a second step, the salt is neutralized with strong mineral acid to precipitate the terephthalic acid.

- [(CO)C6H4(CO2CH2CH2O)]n + 2n MOH → n C6H4(CO2M)2 + n HOCH2CH2OH

- C6H4(CO2M)2 + 2HCl → C6H4(CO2H)2 + 2MCl

This method is particularly tolerant of contamination.[19] The use of NaOH as a base is preferred and the addition of ethanol to the medium speeds up the process. Many catalysts have been evaluated in academic studies.[18]

Acidic hydrolysis

The usual acid employed in this process is sulphuric. Sulphuric acid is corrosive, requiring expensive corrosion resistant alloys to be used in the reaction vessels. Also the recovery of ethylene glycol and the recovery and reuse of the sulphuric acid itself are expensive.[19] These are the likely reasons why acid hydrolysis is not employed commercially in 2022.

Enzymatic hydrolysis

Most petroleum‐based plastics are resistant to microbial degradation, however the ester groups in PET can be targeted. A number of enzymes capable of hydrolysing PET (PETases) have been reported. The appeal of enzymatic hydrolysis is that it can operate at much milder conditions, reducing energy costs. Enzymes are also very precise in their action, reducing the formation of by-products. In April 2020, a French university in collaboration with Carbios announced the discovery of a highly efficient, optimized enzyme claimed to outperform all PET hydrolases reported so far.[26] Enzymatic recycle may require size reduction and amorphisation prior to the depolymerization reaction.[27]

Chemical recycle to molecules other than PET monomers

The chemical recycling where transesterification takes place and other glycols/polyols or glycerol are added to make a polyol which may be used in other ways such as polyurethane production or PU foam production[28][29]

|

|

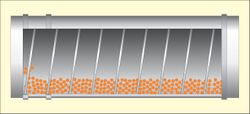

Mechanical recycling

The bales consisting mostly of PET mostly of a single colour are delivered to plants where the bottles may be treated by a variety of processes to convert them into usable feedstocks.[30]

The preferred method for recycling this stream is mechanical recycle, a process in which the resin is remelted, filtered and extruded or molded into new PET articles, such as bottles,[5] films[31] strapping or fibers.[32](Bottles or flakes may be exported from one country to another[33])

If the PET feedstock is not pure enough for mechanical recycle, then chemical recycling back to monomers or oligomers is used. Terephthalic acid (PTA) or dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) and ethylene glycol (EG), or bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (BHET) are popular reaction products. However, chemical recycling to other products is also done.[34][35]

Physical recycling

For physical recycling, especially for recycle to food contact applications, rigorous sorting and cleaning is required.

In Switzerland, for example, the steps that the bottles follow are the following[5] (similar processes are used elsewhere):[36]

- metal separation (to protect the granulator)

- granulation to "flake"

- washing in hot water

- flotation (which separates materials with density <1, notably PE caps and antitamper rings) and sedimentation

- drying

- air current sorting

- washing with caustic soda

This flake is suitable for fibre extrusion. For "bottle to bottle" recycle, the following additional steps are required to correct the molecular weight and meet food contact regulations:

- washing and drying under vacuum

- post washing and drying

- flake sorting

- melt filtration and regranulation

- solid phase polymerization

- moulding into preforms

Melt filtration is typically used to remove contaminants from polymer melts during the extrusion process.[37] There is a mechanical separation of the contaminants within a machine called a "screen changer". A typical system will consist of a steel housing with the filtration medium contained in moveable pistons or slide plates that enable the processor to remove the screens from the extruder flow without stopping production. The contaminants are usually collected on woven wire screens which are supported on a stainless steel plate called a "breaker plate"—a strong circular piece of steel drilled with large holes to allow the flow of the polymer melt. For the recycling of polyester it is typical to integrate a screen changer into the extrusion line. This can be in a pelletizing, sheet extrusion or strapping tape extrusion line.

Purification and decontamination

The success of any recycling concept is hidden in the efficiency of purification and decontamination at the right place during processing and to the necessary or desired extent.

In general, the following applies: The earlier in the process foreign substances are removed, and the more thoroughly this is done, the more efficient the process is.

The high plasticization temperature of PET in the range of 280 °C (536 °F) is the reason why almost all common organic impurities such as PVC,[38] PLA, polyolefin, chemical wood-pulp and paper fibers, polyvinyl acetate, melt adhesive, coloring agents, sugar, and protein residues are transformed into colored degradation products that, in their turn, might release in addition reactive degradation products.[clarification needed] Then, the number of defects in the polymer chain increases considerably. The particle size distribution of impurities is very wide, the big particles of 60–1000 μm—which are visible by naked eye and easy to filter—representing the lesser evil, since their total surface is relatively small and the degradation speed is therefore lower. The influence of the microscopic particles, which—because they are many—increase the frequency of defects in the polymer, is relatively greater.

Besides efficient sorting, the removal of visible impurity particles by melt filtration processes plays a particular part in this case.

In general, one can say that the processes to make PET bottle flakes from collected bottles are as versatile as the different waste streams are different in their composition and quality. In view of technology there is not just one way to do it. Meanwhile, there are many engineering companies that are offering flake production plants and components, and it is difficult to decide for one or other plant design. Nevertheless, there are processes that are sharing most of these principles. Depending on composition and impurity level of input material, the general following process steps are applied.[36]

- Bale opening, briquette opening

- Sorting and selection for different colors, foreign polymers especially PVC, foreign matter, removal of film, paper, glass, sand, soil, stones, and metals

- Pre-washing without cutting

- Coarse cutting dry or combined to pre-washing

- Removal of stones, glass, and metal

- Air sifting to remove film, paper, and labels

- Grinding, dry and / or wet

- Removal of low-density polymers (bottle caps) by density differences

- Hot-wash

- Caustic wash, and surface etching, maintaining intrinsic viscosity and decontamination

- Rinsing

- Clean water rinsing

- Drying

- Air-sifting of flakes

- Automatic flake sorting

- Water circuit and water treatment technology

- Flake quality control

Impurities and material defects

The number of possible impurities and material defects that accumulate in the polymeric material is increasing permanently—when processing as well as when using polymers—taking into account a growing service lifetime, growing final applications and repeated recycling. As far as recycled PET bottles are concerned, the defects mentioned can be sorted in the following groups:

- Reactive polyester OH- or COOH- end groups are transformed into dead or non-reactive end groups, e.g. formation of vinyl ester end groups through dehydration or decarboxylation of terephthalate acid, reaction of the OH- or COOH- end groups with mono-functional degradation products like mono-carbonic acids or alcohols. Results are decreased reactivity during re-polycondensation or re-SSP and broadening the molecular weight distribution.

- The end group proportion shifts toward the direction of the COOH end groups built up through a thermal and oxidative degradation. The results are decrease in reactivity, and increase in the acid autocatalytic decomposition during thermal treatment in presence of humidity.

- Number of polyfunctional macromolecules increases. Accumulation of gels and long-chain branching defects.

- Number, concentration, and variety of nonpolymer-identical organic and inorganic foreign substances are increasing. With every new thermal stress, the organic foreign substances will react by decomposition. This is causing the liberation of further degradation-supporting substances and coloring substances.

- Hydroxide and peroxide groups build up at the surface of the products made of polyester in presence of air (oxygen) and humidity. This process is accelerated by ultraviolet light. During an ulterior treatment process, hydro peroxides are a source of oxygen radicals, which are source of oxidative degradation. Destruction of hydro peroxides is to happen before the first thermal treatment or during plasticization and can be supported by suitable additives like antioxidants.

Taking into consideration the above-mentioned chemical defects and impurities, there is an ongoing modification of the following polymer characteristics during each recycling cycle, which are detectable by chemical and physical laboratory analysis.

In particular:

- Increase of COOH end-groups

- Increase of color number b

- Increase of haze (transparent products)

- Increase of oligomer content

- Reduction in filterability

- Increase of by-products content such as acetaldehyde, formaldehyde

- Increase of extractable foreign contaminants

- Decrease in color L

- Decrease of intrinsic viscosity or dynamic viscosity

- Decrease of crystallization temperature and increase of crystallization speed

- Decrease of the mechanical properties like tensile strength, elongation at break or elastic modulus

- Broadening of molecular weight distribution

The recycling of PET bottles is meanwhile an industrial standard process that is offered by a wide variety of engineering companies.[39]

Processing routes

Recycling processes with polyester are almost as varied as the manufacturing processes based on primary pellets or melt. Depending on purity of the recycled materials, polyester can be used today in most of the polyester manufacturing processes as blend with virgin polymer or increasingly as 100% recycled polymer. Some exceptions like BOPET-film of low thickness, special applications like optical film or yarns through FDY-spinning at > 6000 m/min, microfilaments, and micro-fibers are produced from virgin polyester only.

Simple re-pelletizing of bottle flakes

This process consists of transforming bottle waste into flakes, by drying and crystallizing the flakes, by plasticizing and filtering, as well as by pelletizing. Product is an amorphous re-granulate of an intrinsic viscosity in the range of 0.55–0.7, depending on how complete pre-drying of PET flakes has been done.

Special feature are: Acetaldehyde and oligomers are contained in the pellets at lower level; the viscosity is reduced somehow, the pellets are amorphous and have to be crystallized and dried before further processing.

Processing to:

- A-PET film for thermoforming

- Addition to PET virgin production

- BoPET packaging film

- PET Bottle resin by SSP

- Carpet yarn

- Engineering plastic

- Filaments

- Non-woven

- Packaging stripes

- Staple fibre.

Choosing the re-pelletizing way means having an additional conversion process that is, at the one side, energy-intensive and cost-consuming, and causes thermal destruction. At the other side, the pelletizing step is providing the following advantages:

- Intensive melt filtration

- Intermediate quality control

- Modification by additives

- Product selection and separation by quality

- Processing flexibility increased

- Quality uniformization.

Manufacture of PET-pellets or flakes for bottles (bottle to bottle) and A-PET

This process is, in principle, similar to the one described above; however, the pellets produced are directly (continuously or discontinuously) crystallized and then subjected to a solid-state polycondensation (SSP) in a tumbling drier or a vertical tube reactor. During this processing step, the corresponding intrinsic viscosity of 0.80–0.085 dℓ/g is rebuilt again and, at the same time, the acetaldehyde content is reduced to < 1 ppm.

The fact that some machine manufacturers and line builders in Europe and the United States make efforts to offer independent recycling processes, e.g. the so-called bottle-to-bottle (B-2-B) process, such as Next Generation Recycling (NGR), BePET, Starlinger, URRC or BÜHLER, aims at generally furnishing proof of the "existence" of the required extraction residues and of the removal of model contaminants according to FDA applying the so-called challenge test, which is necessary for the application of the treated polyester in the food sector. Besides this process approval it is nevertheless necessary that any user of such processes has to constantly check the FDA limits for the raw materials manufactured by themselves for their process.

Direct conversion of bottle flakes

Drying

PET polymer is very sensitive to hydrolytic degradation, resulting in severe reduction in its molecular weight, thereby adversely affecting its subsequent melt processability. Therefore, it is essential to dry the PET flakes or granules to a very low moisture level prior to melt extrusion.

PET must be dried to <100 parts per million (ppm) moisture and maintained at this moisture level to minimize hydrolysis during melt processing.[40]

Dehumidifying Drying – These types of dryers circulate hot and de-humidified dry air onto the resin, suck the air back, dry it and then pump again in a closed loop operation. This process reduces moisture level in the PET down to 50ppm or lower. The efficiency of moisture removal depends on the air dew point. If the air dew point is not good, then some moisture remains in the chips and cause IV loss during processing.

Infrared Drying polyester pellets and flakes – A new type of dryer has been introduced in recent years, using Infrared drying (IRD). Due to the high rate of energy transfer with IR heating in combination with the specific wavelength used, the energy costs involved with these systems can be greatly reduced, along with the size. Polyester can be dried and amorphous flake crystallized and dried within only about 15 minutes down to a moisture level of approx. 300ppm in one step, and down to <50 ppm using a buffer hopper to complete the drying in typically under 1 hour

Global statistics

Worldwide, approximately 7.5 million tons of PET were collected in 2011. This gave 5.9 million tons of flake. In 2009 3.4 million tons were used to produce fibre, 500,000 tons to produce bottles, 500,000 tons to produce APET sheet for thermoforming, 200,000 tons to produce strapping tape and 100,000 tons for miscellaneous applications.[41] Thus only approximately 15% of collected PET bottles were actually recycled into new bottles, the rest being used in generally non-recyclable products.

Petcore, the European trade association that fosters the collection and recycling of PET, reported that in the EU 28+2,[14] out of 3.4 Mt bottles sold, 2.1Mt of PET bottles were collected in 2018 (so around 2/3). 1.35Mt of r-PET were produced for which the end uses were:

- 30% sheets & films (half for food contact). (2010: 22%[42])

- 28% bottles (half for food contact). (2010: 25%)

- 24% fibres (2010: 38%)

- 10% strapping (2010: 10%)

- 8% other

NAPCOR reported that for the US and Canada in 2018:[43]

out of 3 Mt bottles sold, 900kt of PET bottles (up from 600kt in 2008[44]) were collected in 2018 (so around 1/3). 700kt of r-PET were produced for which the end uses were:

- 15% sheets & films

- 35% bottles (1/5 for food contact).

- 40% fibres

- 8% strapping

- 1% other

In 2019, 81% of the PET bottles sold in Switzerland were recycled,[45] as in 2012.[46]

In 2018, 90% of the PET bottles sold in Finland were recycled. The high rate of recycling is mostly result of the deposit system in use. The law demands a tax of €0,51 /l for bottles and cans that are not part of a refund system. Thus encouraged by the law, products are included to have a 10¢ to 40¢ deposit that is paid to the recycler of the can or bottle.[47]

rPET end use in 2020 (total of 1,805 million pounds)

- 38% fiber

- 34% beverage bottles

- 14% sheet & film

- 7% non-food bottles

- 5% strapping

- 2% other

PET bottles recycle-rate globally[48][49]

| Japan | US | Europe | India [50] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 72% | 33%[43] | 66%[14] | 90% |

Uses

Re-use of PET bottles

In 2019, 2 billion PET bottles were refilled with mineral water in Germany. There is a plan to make these refillable bottles from rPET.[51]

PET bottles are also repurposed for various uses, including for use in school projects, and for use in solar water disinfection in developing nations, in which empty PET bottles are filled with water and left in the sun to allow disinfection by ultraviolet radiation. PET is useful for this purpose because many other materials (including window glass) that are transparent to visible light are opaque to ultraviolet radiation.[52]

A novel use is as a building material in third-world countries.[53] According to online sources[which?], the bottles, in a labor-intensive process, are filled with sand, then stacked and either mudded or cemented together to form a wall. Some of the bottles can be filled instead with air or water, to admit light into the structure.

Fibres

Most recycled PET is used as apparel fiber. However rPET has also been sold in the form of carpet fiber. Mohawk Industries released everSTRAND in 1999, a 100% post-consumer recycled content PET fiber. Since that time, more than 17 billion bottles have been recycled into carpet fiber.[54] Pharr Yarns, a supplier to numerous carpet manufacturers including Looptex, Dobbs Mills, and Berkshire Flooring,[55] produces a BCF (bulk continuous filament) PET carpet fiber containing a minimum of 25% post-consumer recycled content.

Energy recovery

If it not possible to recycle PET bottles for whatever reason, PET works well as a fuel in waste to energy plants, composed as it is of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, with only trace amounts of catalyst elements (but no sulfur). PET has the energy content of soft coal.

Life cycle analysis

Studies have shown that mechanical recycle has a lower environmental impact than incineration, due to avoided new raw material production.[56]

One study for the USA territory in 2018[57] concluded that recycle PET vs virgin gave reductions in environmental footprint (all forms are covered but bottles dominate the PET stream). Assuming that virgin PET will be used regardless of the existence of recycling:

- Energy 70 → 15 MJ/kg

- Water 9.9 → 10.3 L/kg (this increase due to the intense washing required for mechanical recycle)

- Greenhouse gas emissions 2.8 → 0.9 kgCO2 /kg

See also

- Health and environmental issues with plastic bottles

- Low plastic water bottle

- Plastiki

References

- ↑ "Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Market". January 2023. https://www.fnfresearch.com/polyethylene-terephthalate-pet-market.

- ↑ Benyathiar, Patnarin (2022). "Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Bottle-to-Bottle Recycling for the Beverage Industry: A Review". Polymers 14 (12): 2366. doi:10.3390/polym14122366. PMID 35745942.

- ↑ "2023 US PET Bottle Recycling Rate Reaches Highest Level in Decades; Recycled PET Content in US Bottles Reaches Highest Level Ever". December 12, 2024. https://napcor.com/news/2023-pet-bottle-recycling-reach-new-heights/.

- ↑ "Study: PET recycling process – bottles increasingly environmentally friendly". 19 November 2020. https://newsroom.kunststoffverpackungen.de/en/2020/11/19/study-pet-recycling-process-bottles-increasingly-environmentally-friendly/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 "R-PET: Schweizer Kreislauf – PET-Recycling" (in fr). https://www.petrecycling.ch/fr/savoir/recycling-pet/r-pet-schweizer-kreislauf-kopie.

- ↑ Wöllersdorf, Hard (August 9, 2017). "Study confirms the excellent carbon footprint of recycled PET". https://blog.alpla.com/en/press-release/newsroom/study-confirms-excellent-carbon-footprint-recycled-pet/08-17.

- ↑ Clark Howard, Brian. "Recycling Symbols on Plastics – What Do Recycling Codes on Plastics Mean". The Daily Green (Good Housekeeping). http://www.thedailygreen.com/green-homes/latest/recycling-symbols-plastics-460321?src=soc_fcbk.

- ↑ Chacon, F A (January 2020), "Effect of recycled content and rPET quality on the properties of PET bottles, part I: Optical and mechanical properties", Packaging Technology and Science 33 (9): 347–357, doi:10.1002/pts.2490

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Life Cycle Environmental Impact of PET Water Bottles". 2021. https://nems.nih.gov/Documents/PETWaterBottlesEnvironmentalImpact.pdf.

- ↑ "Energy balance in recycling one PET bottle". February 2025. http://www-g.eng.cam.ac.uk/impee/topics/RecyclePlastics/files/RecyclingEnergyBalance.pdf.

- ↑ "Plastic Packaging Resins". American Chemistry Council. http://www.americanchemistry.com/s_plastics/bin.asp?CID=1102&DID=4645&DOC=FILE.PDF.

- ↑ Szaky, Tom (April 22, 2015). "The Many Challenges of Plastic Recycling". https://sustainablebrands.com/read/waste-not/the-many-challenges-of-plastic-recycling.

- ↑ "Colored PET: Pretty To Look At; Headache For Recyclers". 28 May 2015. https://www.ptonline.com/blog/post/colored-pet-pretty-to-look-at-headache-for-recyclers-.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "PET Market in Europe State of Play". PETCORE. https://www.petcore-europe.org/component/edocman/eunomia-report-2020-pdf/download.html?Itemid=0.

- ↑ Banos Ruiz, Irene; Cwienk, Jeannette (2021-11-17). "How does Germany's bottle deposit scheme work?". DW.COM. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/how-does-germanys-bottle-deposit-scheme-work/a-50923039.

- ↑ "Plastic Recycling" (in en). https://www.bpf.co.uk/Sustainability/Plastics_Recycling.aspx.

- ↑ Möck, Alexandra; Klinge, Johannes (October 13, 2022). "Mechanical recycling is more climate-compatible than chemical recycling". https://www.oeko.de/en/news/latest-news/mechanical-recycling-is-more-climate-compatible-than-chemical-recycling/.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Barnard, Elaine; Rubio Arias, Jose Jonathan; Thielemans, Wim (2021). "Chemolytic depolymerisation of PET: a review". Green Chemistry 23 (11): 3765–3789. doi:10.1039/D1GC00887K.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 G. P. Karayannidis, George P.; D. S. Achilias, Dimitris S. (2007). "Chemical Recycling of Poly(ethylene terephthalate)". Macromol. Mater. Eng. 292 (2): 128–146. doi:10.1002/mame.200600341.

- ↑ Tournier, V.; Topham, C. M.; Gilles, A.; David, B.; Folgoas, C.; Moya-Leclair, E.; Kamionka, E.; Desrousseaux, M.-L. et al. (9 April 2020). "An engineered PET depolymerase to break down and recycle plastic bottles". Nature 580 (7802): 216–219. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2149-4. PMID 32269349. Bibcode: 2020Natur.580..216T. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02545880.

- ↑ Boos, Frank and Thiele, Ulrich "Reprocessing pulverised polyester waste without yellowing", German Patent DE19503055, Publication date: 8 August 1996

- ↑ Fakirov, Stoyko (ed.) (2002) Handbook of Thermoplastic Polyesters, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, pp. 1223 ff, ISBN 3-527-30113-5

- ↑ Laird, Karen (18 January 2022). "Loop, Suez select site in France for first European Infinite Loop facility" (in en). Plastics News. https://www.plasticsnews.com/news/loop-industries-suez-select-site-normandy-first-european-infinite-loop-facility.

- ↑ Toto, Deanne (1 Feb 2021). "Eastman invests in methanolysis plant in Kingsport, Tennessee" (in en). Recycling Today. https://www.recyclingtoday.com/article/eastman-chemical-recycling-plastics-investment/.

- ↑ Umdagas, Luqman; Orozco, Rafael; Heeley, Kieran; Thom, William; Al-Duri, Bushra (April 2025). "Advances in chemical recycling of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) via hydrolysis: A comprehensive review". Polymer Degradation and Stability 234. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2025.111246.

- ↑ Tournier, V. (8 April 2020). "An engineered PET depolymerase to break down and recycle plastic bottles". Nature 580 (7802): 216–9. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2149-4. PMID 32269349. Bibcode: 2020Natur.580..216T.

- ↑ Singh, Avantika; Rorrer, Nicholas A.; Nicholson, Scott R.; Erickson, Erika; DesVeaux, Jason S.; Avelino, Andre F. T.; Lamers, Patrick; Bhatt, Arpit et al. (15 September 2021). "Techno-economic, life-cycle, and socioeconomic impact analysis of enzymatic recycling of poly(ethylene terephthalate)" (in English). Joule 5 (9): 2479–2503. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2021.06.015. ISSN 2542-4785. Bibcode: 2021Joule...5.2479S.

- ↑ Makuska, Ricardas (2008). "Glycolysis of industrial poly(ethylene terephthalate) waste directed to bis(hydroxyethylene) terephthalate and aromatic polyester polyols". Chemija 19 (2): 29–34. https://mokslozurnalai.lmaleidykla.lt/publ/0235-7216/2008/2/29-34.pdf.

- ↑ "Arropol | Arropol Chemicals" (in en-US). https://arropol.com/.

- ↑ "Processing". Petcore Europe. https://www.petcore-europe.org/processing.html.

- ↑ "Plastic Packaging Resins". American Chemistry Council. http://www.americanchemistry.com/s_plastics/bin.asp?CID=1102&DID=4645&DOC=FILE.PDF.

- ↑ "Recycled Products". Petcore Europe. https://www.petcore-europe.org/recycled-products.html.

- ↑ K. Hanaki: Urban Environmental Management and Technology, ISBN 9784431783978, p. 104

- ↑ Shirazimoghaddam, Shadi; Amin, Ihsan; Faria Albanese, Jimmy A; Shiju, N. Raveendran (2023-01-03). "Chemical Recycling of Used PET by Glycolysis Using Niobia-Based Catalysts" (in en). ACS Engineering Au 3 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1021/acsengineeringau.2c00029. ISSN 2694-2488. PMID 36820227.

- ↑ Jehanno, Coralie; Pérez-Madrigal, Maria M.; Demarteau, Jeremy; Sardon, Haritz; Dove, Andrew P. (2018-12-21). "Organocatalysis for depolymerisation" (in en). Polymer Chemistry 10 (2): 172–186. doi:10.1039/C8PY01284A. ISSN 1759-9962. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2019/py/c8py01284a.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 PET-Recycling Forum; "Current Technological Trends in Polyester Recycling"; 9th International Polyester Recycling Forum Washington, 2006; São Paulo; ISBN 3-00-019765-6

- ↑ Melt Filtration Options and Alternatives

- ↑ Paci, M; La Mantia, F.P (January 1999). "Influence of small amounts of polyvinylchloride on the recycling of polyethyleneterephthalate". Polymer Degradation and Stability 63 (1): 11–14. doi:10.1016/S0141-3910(98)00053-6.

- ↑ Thiele, Ulrich K. (2007) Polyester Bottle Resins Production, Processing, Properties and Recycling, PETplanet Publisher GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany, pp. 259 ff, ISBN 978-3-9807497-4-9

- ↑ http://infohouse.p2ric.org/ref/14/13543.pdf PET Drying Best Practices

- ↑ "- PCI Wood Mackenzie" (in en-US). http://www.pcipetpackaging.co.uk.

- ↑ "Post consumer PET recycling in Europe 2010". PCI. https://www.petcore-europe.org/component/edocman/pci-report-2010-pdf/download.html?Itemid=0.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Postconsumer PET Recycling Activity in 2018". https://napcor.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Postconsumer-PET-Recycling-Activity-in-2018.pdf.

- ↑ Nicholas Dege: The Technology of bottled water, p. 431, John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 9781444393323

- ↑ "Chiffres indicateurs et taux" (in fr-CH). https://www.swissrecycling.ch/fr/substances-valorisables-savoir/chiffres-indicateurs-et-taux.

- ↑ http://www.bafu.admin.ch/dokumentation/medieninformation/00962/index.html?lang=fr&msg-id=50084 (page visited on 4 November 2013).

- ↑ "Deposit refund system". https://www.palpa.fi/beverage-container-recycling/deposit-refund-system/.

- ↑ Japan streets ahead in global plastic recycling race Primary source is 『Plastic Waste Management Institute, Tokyo http://www.pwmi.or.jp/ei/index.htm』

- ↑ "Global Plastic Bottle Recycling Market-Industry Analysis and Forecast (2020–2027)" (in en-GB). https://www.prfire.co.uk/global-plastic-bottle-recycling-market-industry-analysis-and-forecast-2020-2027/.

- ↑ http://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/india-recycles-90-of-its-pet-waste-outperforms-japan-europe-and-us-study/story-yqphS1w2GdlwMYPgPtyb2L.html NCL and PET Packaging Association for Clean Environment (PACE) Data release Feb 2017. The figure is strikingly high and could place India as among the top recycles of PET. The reason is thought not to be due to a strong recycling culture or infrastructure at the consumer end, but by ragpickers who collect and sell the bottles discarded as normal trash to reprocessors. The industry is supposed to be a ₹3200 crore one>

- ↑ "Petainer support refPET in German market". 21 April 2021. https://www.petainer.com/petainer-and-german-wells-cooperative-transition-refillable-pet-bottles-to-30-rpet/.

- ↑ Spuhler, Dorothee; Meierhofer, Regula. "SODIS". Seecon. http://www.sswm.info/content/sodis.

- ↑ "Dune Towers Plastic Bottle House constructed in Sri Lanka". 21 April 2021. https://www.dunetowers.com/accommodation/house-kalpitiya/.

- ↑ everSTRAND Carpet-inspectors-experts.com archive 2008-03-17

- ↑ Simply Green Carpet – A Berkshire Flooring Brand. simplygreencarpet.com

- ↑ Chilton, Tom; Burnley, Stephen; Nesaratnam, Suresh (October 2010). "A life cycle assessment of the closed-loop recycling and thermal recovery of post-consumer PET". Resources, Conservation and Recycling 54 (12): 1241–1249. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.04.002. Bibcode: 2010RCR....54.1241C.

- ↑ "Life cycle impacts for postconsumer recycled resins: PET, HDPE, and PP". Franklin Associates. https://plasticsrecycling.org/images/library/2018-APR-LCI-report.pdf.

|