Physics:Van der Waals equation

The van der Waals equation, named for its originator, the Dutch physicist Johannes Diderik van der Waals, is an equation of state that extends the ideal gas law to include the non-zero size of gas molecules and the interactions between them (both of which depend on the specific substance). As a result the equation is able to model the phase change from liquid to gas, and vice versa. It also produces simple analytic expressions for the properties of real substances that shed light on their behavior. One common way to write this dimensional equation is:[1][2]

where is pressure, is temperature, and is the molar volume, where is the total volume, and is the number of molecules. is the universal gas constant, is Avogadro's constant, and is Boltzmann's constant. The experimentally determinable, substance specific constant expresses the strength of the molecular interactions, it has the dimension pressure times molar volume squared. The experimentally determinable, substance specific constant denotes the excluded molar volume, where is the volume excluded due to the finite size of the molecules; it is four times the volume of all the molecules.[3]

In his book (see references [2] and [3]) Boltzmann wrote equations using (specific volume) in place of (molar volume), Gibbs did also, and so do most engineers. There is no essential difference between equations written with either of these two properties. Equations of state written using molar volume contain while those using specific volume contain , where the substance specific is the molar mass.

Once and are experimentally determined for a given substance, the van der Waals equation can be used to predict the boiling point at any given pressure, the critical point (defined by pressure and temperature values, such that the substance cannot be liquified either when no matter how low the temperature, or when no matter how high the pressure), and other attributes. These predictions are accurate for only a few substances. For most simple fluids it is only a valuable approximation. The equation also explains why superheated liquids can exist above their boiling point and subcooled vapors can exist below their condensation point.

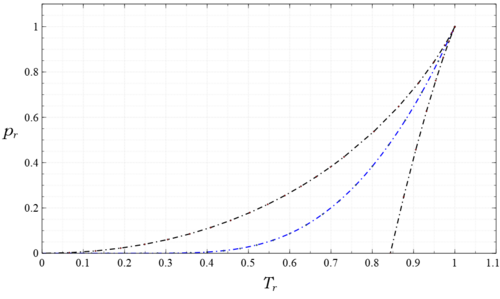

thumb|400px| The graph on the right is a plot of vs calculated from the equation at four constant pressure values. On the red isobar, , the slope is positive over the entire range, (although the plot only shows a finite quadrant). This describes a fluid as a gas for all , and is characteristic of all isobars The green isobar, , has a physically unreal negative slope, hence shown dotted gray, between its local minimum, , and local maximum, . This describes the fluid as two disconnected branches; a gas for , and a denser liquid for .[4]

The thermodynamic requirements of mechanical, thermal, and material equilibrium together with the equation specify two points on the curve, , and , shown as green circles that designate the coexisting boiling liquid and condensing gas respectively. Heating the fluid in this state increases the fraction of gas in the mixture; its , an average of and weighted by this fraction, increases while remains the same. This is shown as the dotted gray line, because it does not represent a solution of the equation; however, it does describe the observed behavior. The points above , superheated liquid, and those below it, subcooled vapor, are metastable; a sufficiently strong disturbance causes them to transform to the stable alternative. Consequently they are shown dashed. Finally the points in the region of negative slope are unstable. All this describes a fluid as a stable gas for , a stable liquid for , and a mixture of liquid and gas at , that also supports metastable states of subcooled gas and superheated liquid. It is characteristic of all isobars , where is a function of .[5] The orange isobar is the critical one on which the minimum and maximum are equal. The black isobar is the limit of positive pressures, although drawn solid none of its points represent stable solutions, they are either metastable (positive or zero slope) or unstable (negative slope. All this is a good explanation of the observed behavior of fluids.

Relationship to the ideal gas law

The ideal gas law follows from the van der Waals equation whenever is sufficiently large (or correspondingly whenever the density, , is sufficiently small), Specifically[6][7]

- when , then is numerically indistinguishable from ,

- and when , then is numerically indistinguishable from .

Putting these two approximations into the van der Waals equation when v is large enough that both inequalities are satisfied reduces it to

which is the ideal gas law.[8] This is not surprising since the van der Waals equation was constructed from the ideal gas equation in order to obtain an equation valid beyond the limit of ideal gas behavior.

What is truly remarkable is the extent to which van der Waals succeeded. Indeed, Epstein in his classic thermodynamics textbook began his discussion of the van der Waals equation by writing: "In spite of its simplicity, it comprehends both the gaseous and the liquid state and brings out, in a most remarkable way, all the phenomena pertaining to the continuity of these two states".[9] Also in Volume 5 of his Lectures on Theoretical Physics Sommerfeld, in addition to noting that "Boltzmann[10] described van der Waals as the Newton of real gases", also wrote "It is very remarkable that the theory due to van der Waals is in a position to predict, at least qualitatively, the unstable [referring to superheated liquid, and subcooled vapor now called metastable] states" that are associated with the phase change process.[11]

Utility of the equation

The equation has been, and remains very useful because:[12]

- Its coefficient of thermal expansion, has a simple analytic expression [this is also true of its isothermal compressibility, ]

- It explains the existence of the critical point and the liquid --- vapor phase transition including the observed metastable states

- it establishes the law of corresponding states

- its specific heat at constant volume, , can be shown to be a function of only, and its thermodynamic properties, internal energy , entropy , as well as the specific heat at constant pressure have simple analytic expressions [this is also true of enthalpy , Helmholtz free energy , and Gibbs free energy ]

- Its Joule-Thomson coefficient and associated inversion curve, which were instrumental in the commercial liquefaction of gases have simple analytic expressions.

The equation also plays an important role in the modern theory of phase transitions.[13] It depicts the liquid metals, Mercury and Cesium, quantitatively, and describes most real fluids qualitatively.[14] Consequently it can be regarded as one member of a family of equations of state,[15] that depend on a molecular parameter such as the critical compressibility factor, , or the Pitzer (acentric) factor, , where is a dimensionless saturation pressure, and log is the logarithm base 10.[16]

All this makes it a worthwhile pedagogical tool for physics, chemistry, and engineering lecturers, in addition to being a useful mathematical model which can aid student understanding.

History

In 1857 Rudolf Clasius published The Nature of the Motion which We Call Heat. In it he derived the relation for the pressure, , in a gas with particles per unit volume (number density), mass , and mean square speed . He then noted that using the classical laws of Boyle and Charles one could write with a constant of proportionality. Hence temperature was proportional to the average kinetic energy of the particles.[17] This article inspired further work based on the twin ideas that substances are composed of indivisible particles, and that heat is a consequence of the particle motion as governed by Newton's laws. The work, known as the kinetic theory of gases, was done principally by James Clerk Maxwell, and Ludwig Boltzmann. At about the same time J. Willard Gibbs also contributed, and advanced it by converting it into statistical mechanics.[18]

This environment influenced Johannes Diderik van der Waals. After initially pursuing a teaching credential, he was accepted for doctoral studies at the University of Leiden under Pieter Rijke. This led, in 1873, to a dissertation that provided a simple, particle based, equation that described the gas-liquid change of state, the origin of a critical temperature, and the concept of corresponding states.[7] The equation is based on two premises, first that fluids are composed of particles with non-zero volumes, and second that at a large enough distance each particle exerts an attractive force on all other particles in its vicinity. These forces were called by Boltzmann van der Waals cohesive forces.[19]

In 1869 Irish professor of chemistry Thomas Andrews at Queen's University Belfast in a paper entitled On the Continuity of the Gaseous and Liquid States of Matter,[20] displayed an experimentally obtained set of isotherms of carbonic acid, HCO, that showed at low temperatures a jump in density at a certain pressure, while at higher temperatures there was no abrupt change; the figure can be seen here. Andrews called the isotherm at which the jump just disappeared the critical point. Given the similarity of the titles of this paper and van der Waals subsequent thesis one might think that van der Waals set out to develop a theoretical explanation of Andrews' experiments. However the opposite is true, van der Waals began work by trying to determine a mollecular attraction that appeared in Laplace's theory of capillarity, and only after establishing his equation tested it using Andrews results.[21]

By 1877 sprays of both liquid oxygen and liquid nitrogen had been produced, and a new field of research, low temperature physics, had been opened. The van der Waals equation played a part in all this especially with respect to the liquefaction of hydrogen and helium which was finally achieved in 1908.[22] From measurements of and in two states with the same density, the van der Waals equation produces the values and .[23] Thus from two such measurements of pressure and temperature one could determine and , and from these values calculate the expected critical pressure, temperature, and molar volume. Goodstein summarized this contribution of the van der Waals equation as follows:[24]

All this labor required considerable faith in the belief that gas-liquid systems were all basically the same, even if no one had ever seen the liquid phase. This faith arose out of the repeated success of the van der Waals theory, which is essentially a universal equation of state, independent of the details of any particular substance once it has been properly scaled. ... As a result, not only was it possible to believe that hydrogen could be liquefied. but it was even possible to predict the necessary temperature and pressure.

Van der Waals was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1910, in recognition of the contribution of his formulation of this "equation of state for gases and liquids".

As noted previously, modern day studies of first order phase changes make use of the van der Waals equation together with the Gibbs criterion, equal chemical potential of each phase, as a model of the phenomenon. This model has an analytic coexistence (saturation) curve that was apparently known to Gibbs, and was re-derived in a beautifully simple and elegant manner by Lekner;[25] a brief summary of which is presented in a subsequent section, and a more complete discussion in the Maxwell Construction.

Critical point and corresponding states

Figure 1 shows four isotherms of the van der Waals equation (abbreviated as vdW) on a pressure, molar volume plane. The essential character of these curves is that:

1) at some critical temperature, the slope is negative, , everywhere except at a single point, the critical point, , where both the slope and curvature are zero, ;

2) at higher temperatures the slope of the isotherms is everywhere negative (values of for which the equation has 1 real root for );

3) at lower temperatures there are two points on each isotherm where the slope is zero (values of for which the equation has 3 real roots for )

Evaluating the two partial derivatives in 1) using the vdW equation and equating them to zero produces, , and using these in the equation gives .[26]

This calculation can be done algebraically by noting that the vdW equation can be written as a cubic in , which at the critical point is, . Moreover, at the critical point all three roots coalesce so it can also be written as Then dividing the first by , and noting that these two cubic equations are the same when all their coefficients are equal gives three equations whose solution produces the previous results for .[27][28]

Using these critical values to define reduced properties renders the equation in the dimensionless form used to construct Fig. 1 This dimensionless form is a similarity relation; it indicates that all vdW fluids at the same will plot on the same curve. It expresses the law of corresponding states which Boltzmann described as follows:[29]

All the constants characterizing the gas have dropped out of this equation. If one bases measurements on the van der Waals units [Boltzmann's name for the reduced quantities here], then he obtains the same equation of state for all gases. ... Only the values of the critical volume, pressure, and temperature depend on the nature of the particular substance; the numbers that express the actual volume, pressure, and temperature as multiples of the critical values satisfy the same equation for all substances. In other words, the same equation relates the reduced volume, reduced, pressure, and reduced temperature for all substances.

Obviously such a broad general relation is unlikely to be correct; nevertheless, the fact that one can obtain from it an essentially correct description of actual phenomena is very remarkable.

This "law" is just a special case of dimensional analysis in which an equation containing 6 dimensional quantities, , and 3 dimensions, [p], [v], [T], must be expressible in terms of 6-3=3 dimensionless groups.[30] Here is a characteristic molar volume, a characteristic pressure, and a characteristic temperature, and the 3 dimensionless groups are . Note that , , and . As mentioned earlier, recent research has indicated that there is a family of equations of state that depend on another dimensionless group as well, and this provides a more exact correlation of properties. Nevertheless, as Boltzmann observed, the van der Waals equation provides an essentially correct description.

Notice that the vdW equation produces , while for most real fluids .[31] Thus most real fluids do not satisfy this condition, and consequently their behavior is only described qualitatively by the vdW equation. However, as mentioned previously, research has shown that the vdW equation of state is a member of a family of state equations that include the Pitzer (acentric) factor, , and the liquid metals, Mercury and Cesium, are well approximated by it.[32] [33]

Thermodynamic properties

The properties molar internal energy, , and entropy, , defined by the first and second laws of thermodynamics, hence all thermodynamic properties of a simple compressible substance, can be specified, up to a constant of integration, by two measurable functions, a mechanical equation of state, , and a constant volume specific heat, .[34][35]

Internal energy and specific heat at constant volume

The internal energy is given by the energetic equation of state,[36] [37] where is an arbitrary constant of integration.

Now in order for to be an exact differential, namely that be continuous with continuous partial derivatives, its second mixed partial derivatives must also be equal, . Then with this condition can be written simply as . Differentiating for the vdW equation gives , so . Consequently for a vdW fluid exactly as it is for an ideal gas. To keep things simple it is regarded as a constant here, with a number. Then both integrals can be easily evaluated and the result is This is the energetic equation of state for a perfect vdW fluid. By making a dimensional analysis (what might be called extending the principle of corresponding states to other thermodynamic properties) it can be written simply in reduced form as where and C is a dimensionless constant.

Enthalpy

The enthalpy is , and the product is just . Then is simplyThis is the enthalpic equation of state for a perfect vdW fluid, or in reduced form

Entropy

The entropy is given by the entropic equation of state:[38][39] Using as before, and integrating the second term using we obtain simply This is the entropic equation of state for a perfect vdW fluid, or in reduced form

Gibbs free energy

The Gibbs free energy is so combining the previous results gives This is the Gibbs free energy for a perfect vdW fluid, or in reduced form

The thermodynamic derivatives: α, κT and cp

The two first partial derivatives of the vdW equation are The first equation is , while the second is , where , the isothermal compressibility, is a measure of the relative increase of volume from an increase of pressure, at constant temperature, while , the coefficient of thermal expansion, is a measure of the relative increase of volume from an increase of temperature, at constant pressure. Therefore In the limit while . Since the vdW equation in this limit becomes , finally . Both of these are the ideal gas values, which is consistent because, as noted earlier, the vdW fluid behaves like an ideal gas in this limit.

The specific heat at constant pressure, is defined as the partial derivative . However, it is not independent of , they are related by the Mayer equation, .[40] [41] Then the two partials of the vdW equation can be used to express as Here in the limit , , which is also the ideal gas result as expected; however the limit gives the same result, which does not agree with experiments on liquids.

In this liquid limit we also find , namely that the vdW liquid is incompressible. Moreover, since , it is also mechanically incompressible, that is faster than .

Finally , and are all infinite on the curve . This curve, called the spinodal curve, is defined by , and is discussed at length in the next section.

Stability

According to the extremum principle of thermodynamics and , namely that at equilibrium the entropy is a maximum. This leads to a requirement that .[42] This mathematical criterion expresses a physical condition which Epstein[43] described as follows:

"It is obvious that this middle part, dotted in our curves [the place where the requirement is violated, dashed gray in Fig. 1 and repeated here], can have no physical reality. In fact, let us imagine the fluid in a state corresponding to this part of the curve contained in a heat conducting vertical cylinder whose top is formed by a piston. The piston can slide up and down in the cylinder, and we put on it a load exactly balancing the pressure of the gas. If we take a little weight off the piston, there will no longer be equilibrium and it will begin to move upward. However, as it moves the volume of the gas increases and with it its pressure. The resultant force on the piston gets larger, retaining its upward direction. The piston will, therefore, continue to move and the gas to expand until it reaches the state represented by the maximum of the isotherm. Vice versa, if we add ever so little to the load of the balanced piston, the gas will collapse to the state corresponding to the minimum of the isotherm"

While on an isotherm this requirement is satisfied everywhere so all states are gas, those states on an isotherm, which lie between the local minimum, , and local maximum, , for which (shown dashed gray in Fig. 1), are unstable and thus not observed. This is the genesis of the phase change; there is a range , for which no observable states exist. The states for are liquid and for are vapor; due to gravity the denser liquid lies below the vapor. The transition points, states with zero slope, are called spinodal points. Their locus is the spinodal curve that separates the regions of the plane for which liquid, vapor, and gas exist from a region where no observable states exist. This spinodal curve is obtained here from the vdW equation by differentiation (or equivalently ) as A projection of this space curve is plotted in Fig.1 as the black dash dot curve. It passes through the critical point which is, of course, also a spinodal point.

Saturation

Although the gap in delimited by the two spinodal points on an isotherm (e.g. shown in Fig. 1) is the origin of the phase change, the spinodal points do not represent its full extent, because both states, saturated liquid and saturated vapor coexist in equlilbrium; they both must have the same pressure as well as the same temperature.[44] Thus the phase change is characterized, at temperature , by a pressure that lies between that of the minimum and maximum spinodal points, and with molar volumes of liquid, and vapor .. Then from the vdW equation applied to these saturated liquid and vapor states These two vdW equations contain 4 variables, , so another equation is required in order to specify the values of 3 of these variables uniquely in terms of a fourth. Such an equation is provided here by the equality of the Gibbs free energy in the saturated liquid and vapor states, .[45] This condition of material equilibrium can be obtained from a simple physical argument as follows: the energy required to vaporize a mole is from the second law at constant temperature , and from the first law at constant pressure . Equating these two, rearranging, and recalling that produces the result.

The Gibbs free energy is one of the 4 thermodynamic potentials whose partial derivatives produce all other thermodynamics state properties;[46] its differential is . Integrating this over an isotherm from to , noting that the pressure is the same at each endpoint, and setting the result to zero yields Here because is a multivalued function, the integral must be divided into 3 parts corresponding to the 3 real roots of the vdW equation in the form, (this can be visualized most easily by imagining Fig. 1 rotated 90); the result is a special case of material equilibrium.[47] The last equality, which follows from integrating , is the Maxwell equal area rule which requires that the upper area between the vdW curve and the horizontal through be equal to the lower one.[48] This form means that the thermodynamic restriction that fixes is specified by the equation of state itself, . Using the equation for the Gibbs free energy obtained previously for the vdW equation applied to the saturated vapor state and subtracting the result applied to the saturated liquid state produces, This is a third equation that along with the two vdW equations above can be solved numerically. This has been done given a value for either or , and tabular results presented;[49][50] however, the equations also admit an analytic parametric solution first obtained by Gibbs and later more simply, but elegantly, by Lekner.[51] Details of this solution may be found in the Maxwell Construction; the results are where

and the parameter is given physically by . The values of all other property discontinuities across the saturation curve also follow from this solution.[52] These functions define the coexistence curve which is the locus of the saturated liquid and saturated vapor states of the vdW fluid. The curve is plotted in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, two projections of the state surface. These curves agree exactly with the numerical results referenced earlier.

Referring back to Fig. 1 the isotherms for are discontinuous. Considering as an example, it consists of the two separate green segments. The solid segment above the green circle on the left, and below the one on the right correspond to stable states, the dots represent the saturated liquid and vapor states that comprise the phase change, and the two green dotted segments below and above the dots are metastable states, superheated liquid and subcooled vapor, that are created in the process of phase transition, have a short lifetime, then devolve into their lower energy stable alternative.

In his treatise of 1898 in which he described the van der Waals equation in great detail Boltzmann discussed these states in a section titled "Undercooling, Delayed evaporation";[53] they are now denoted subcooled vapor, and superheated liquid. Moreover, it has now become clear that these metastable states occur regularly in the phase transition process. In particular processes that involve very high heat fluxes create large numbers of these states, and transition to their stable alternative with a corresponding release of energy can be dangerous. Consequently there is a pressing need to study their thermal properties.[54]

In the same section Boltzmann also addressed and explained the negative pressures which some liquid metastable states exhibit (for example of Fig. 1). He concluded that such liquid states of tensile stresses were real, as did Tien and Lienhard many years later who wrote "The van der Waals equation predicts that at low temperatures liquids sustain enormous tension...In recent years measurements have been made that reveal this to be entirely correct."[55]

Even though the phase change produces a mathematical discontinuity in the homogeneous fluid properties, for example , there is no physical discontinuity.[56] As the liquid begins to vaporize the fluid becomes a heterogeneous mixture of liquid and vapor whose molar volume varies continuously from to according to the equation of state where is the mole fraction of the vapor. This equation is called the lever rule and applies to other properties as well.[57][58] The states it represents form a horizontal line connecting the same colored dots on an isotherm, but not shown in Fig. 1 as noted already since it is a distinct equation of state for the heterogeneous combination of liquid and vapor components.

Extended corresponding states behavior and the van der Waals Equation

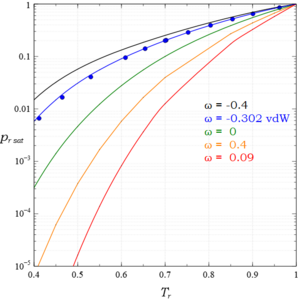

As discussed previously the idea of corresponding states originated when van der Waals cast his equation in the dimensionless form, . However, as Boltzmann noted, such a simple representation could not correctly describe all substances. Indeed, the saturation analysis of this form produces , namely all substances have the same dimensionless coexistence curve.[59] In order to avoid this paradox an extended principle of corresponding states has been suggested in which where is a substance dependent dimensionless parameter related to the only physical feature associated with an individual substance, its critical point.

The first candidate for was the critical compressibility factor , but because that quantity is difficult to measure accurately, the acentric factor developed by Kenneth Pitzer, , is more useful. The saturation pressure in this situation is represented by a one parameter family of curves, . Several investigators have produced correlations of saturation data for a number of substances, the best is that of Dong and Lienhard,[60]

which has an rms error of

over the range

Figure 3 is a plot of vs . for various values of as given by this equation. The ordinate is logarithmic in order to show the behavior at pressures far below the critical where differences among the various substances (indicated by varying values of ) are more pronounced.

Figure 4 is another plot of the same equation showing as a function of for various values of . It includes data from 51 substances including the vdW fluid over the range . This plot shows clearly that the vdW fluid () is a member of the class of real fluids; indeed it quantitatively describes the behavior of the liquid metals cesium () and mercury () whose values of are close to the vdW value. However, it describes the behavior of other fluids only qualitatively, because specific numerical values are modified by differing values of their Pitzer factor, .

Joule-Thomson coefficient and the inversion curve

The Joule-Thomson coefficient, , is of practical importance because the two end states of a throttling process () lie on a constant enthalpy curve. Although ideal gases, for which , do not change temperature in such a process, real gases do, and it is important in applications to know whether they heat up or cool down.[61]

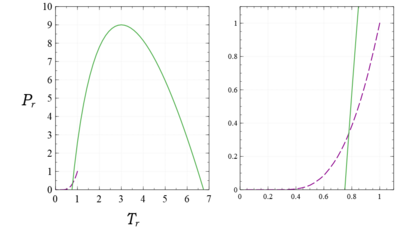

This coefficient can be found in terms of the previously described derivatives as,[62] so when is positive the gas temperature decreases when it passes through a throttle, and if it is negative the temperature increases. Therefore the condition defines a curve that separates the region of the plane where from the region where it is less than zero. This curve is called the inversion curve, and its equation is . Using the expression for derived previously for the van der Waals equation this is Note that for there will be cooling for or in terms of the critical temperature . As Sommerfeld noted, "This is the case with air and with most other gases. Air can be cooled at will by repeated expansion and can finally be liquified."[63]

The inversion curve can be found by solving its equation for

, and substituting into the vdW equation. This produces

, where, for simplicity,

have been replaced by

.

The maximum of this, quadratic, curve occurs, with , for which gives , or , and the corresponding . The zeros of the inversion curve , are, making use of the quadratic formula, , or and ( and ). In terms of the dimensionless variables, the zeros are at and , while the maximum is , and occurs at . Note from Fig. 5 that there is an overlap between the saturation curve and the inversion curve plotted there. This region is shown enlarged in the right hand graph of the figure. Therefore a van der Waals gas can be liquified by passing it through a throttle under the proper conditions; real gases are liquified in this way.

Compressibility factor

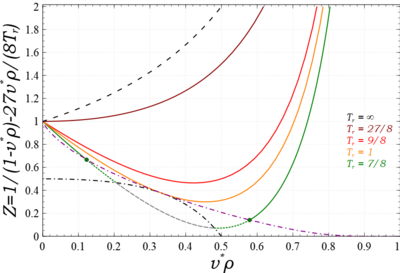

Real gases can be characterized by their difference from ideal. This is done by writing the mechanical equation of state in the form where , called the compressibility factor, is usually expressed either as a function of pressure and temperature, or density and temperature, and in each case in the limit or , , the ideal gas value. In the second case .[64] Thus for a van der Waals fluid the compressibility factor is , or in terms of reduced variables where . At the critical point, , .

In the limit , (for finite ); the fluid behaves like an ideal gas, a point noted several times earlier. Note additionally that the derivative for , and when this is . The slope is positive or negative depending on whether is greater than or less than , and becomes infinitely large negative as approaches .

Figure 6 shows a plot of various isotherms of vs . Also shown are the spinodal and coexistence curves described previously. The subcritical isotherm consists of stable, metastable, and unstable segments, and are identified the same as they were in Fig. 1. Also included are the zero initial slope isotherm and the one corresponding to infinite temperature.

By plotting vs using as a parameter, one obtains the generalized compressibility chart for a vdW gas, which is shown in Fig. 7. Like all other vdW properties, this is not quantitatively correct for most gases but it has the correct qualitative features as can be seen by comparison with this figure which was produced from data using real gases.[65][66] The two graphs are similar, including the caustic generated by the crossing isotherms; they are qualitatively very much alike.

Virial expansion

Statistical mechanics suggests that can be expressed by a power series called a virial expansion,[67] The functions are the virial coefficients; the th term represents a particle interaction.

If we note in the expression for that for , the term can be expanded in an absolutely convergent series; this yields This is the virial expansion for the van der Waals fluid. The first virial coefficient is the slope of at . Notice that it can be positive or negative depending on whether or not , which agrees with the result found previously by differentiation.

Gas mixtures

If a mixture of gases is being considered, and each gas has its own (attraction between molecules) and (volume occupied by molecules) values, then and for the mixture can be calculated as

- = total number of moles of gas present,

- for each , = number of moles of gas present, and

- [68][69]

- [68][69]

and the rule of adding partial pressures becomes invalid if the numerical result of the equation is significantly different from the ideal gas equation .

Derivation

Textbooks in physical chemistry generally give two derivations of the title equation.[who?] One is the conventional derivation that goes back to Van der Waals, a mechanical equation of state that cannot be used to specify all thermodynamic functions; the other is a statistical mechanics derivation that makes explicit the intermolecular potential neglected in the first derivation.[citation needed] A particular advantage of the statistical mechanical derivation is that it yields the partition function for the system, and allows all thermodynamic functions to be specified (including the mechanical equation of state).[citation needed]

Conventional derivation

Consider one mole of gas composed of non-interacting point particles that satisfy the ideal gas law:(see any standard Physical Chemistry text, op. cit.)

Next, assume that all particles are hard spheres of the same finite radius r (the Van der Waals radius). The effect of the finite volume of the particles is to decrease the available void space in which the particles are free to move. We must replace V by V − b, where b is called the excluded volume (per mole) or "co-volume". The corrected equation becomes

The excluded volume is not just equal to the volume occupied by the solid, finite-sized particles, but actually four times the total molecular volume for one mole of a Van der waals' gas. To see this, we must realize that a particle is surrounded by a sphere of radius 2r (two times the original radius) that is forbidden for the centers of the other particles. If the distance between two particle centers were to be smaller than 2r, it would mean that the two particles penetrate each other, which, by definition, hard spheres are unable to do.

The excluded volume for the two particles (of average diameter d or radius r) is

- ,

which, divided by two (the number of colliding particles), gives the excluded volume per particle:

- ,

So b′ is four times the proper volume of the particle. It was a point of concern to Van der Waals that the factor four yields an upper bound; empirical values for b′ are usually lower. Of course, molecules are not infinitely hard, as Van der Waals thought, and are often fairly soft. To obtain the excluded volume per mole we just need to multiply by the number of molecules in a mole, i.e. by the avogadro number:

- .

Next, we introduce a (not necessarily pairwise) attractive force between the particles. Van der Waals assumed that, notwithstanding the existence of this force, the density of the fluid is homogeneous; furthermore, he assumed that the range of the attractive force is so small that the great majority of the particles do not feel that the container is of finite size.[citation needed] Given the homogeneity of the fluid, the bulk of the particles do not experience a net force pulling them to the right or to the left. This is different for the particles in surface layers directly adjacent to the walls. They feel a net force from the bulk particles pulling them into the container, because this force is not compensated by particles on the side where the wall is (another assumption here is that there is no interaction between walls and particles, which is not true, as can be seen from the phenomenon of droplet formation; most types of liquid show adhesion). This net force decreases the force exerted onto the wall by the particles in the surface layer. The net force on a surface particle, pulling it into the container, is proportional to the number density. On considering one mole of gas, the number of particles will be NA

- .

The number of particles in the surface layers is, again by assuming homogeneity, also proportional to the density. In total, the force on the walls is decreased by a factor proportional to the square of the density, and the pressure (force per unit surface) is decreased by:

- ,

so that:

Upon writing n for the number of moles and nVm = V, the equation obtains the second form given above:

It is of some historical interest to point out that Van der Waals, in his Nobel prize lecture, gave credit to Laplace for the argument that pressure is reduced proportional to the square of the density.[70]

Statistical thermodynamics derivation

The canonical partition function Z of an ideal gas consisting of N = nNA identical (non-interacting) particles, is:[71][72]

where is the thermal de Broglie wavelength:

with the usual definitions: h is the Planck constant, m the mass of a particle, k the Boltzmann constant and T the absolute temperature. In an ideal gas z is the partition function of a single particle in a container of volume V. In order to derive the Van der Waals equation we assume now that each particle moves independently in an average potential field offered by the other particles. The averaging over the particles is easy because we will assume that the particle density of the Van der Waals fluid is homogeneous. The interaction between a pair of particles, which are hard spheres, is taken to be:

r is the distance between the centers of the spheres and d is the distance where the hard spheres touch each other (twice the Van der Waals radius). The depth of the Van der Waals well is .

Because the particles are not coupled under the mean field Hamiltonian, the mean field approximation of the total partition function still factorizes:

- ,

but the intermolecular potential necessitates two modifications to z. First, because of the finite size of the particles, not all of V is available, but only V − Nb', where (just as in the conventional derivation above):

- .

Second, we insert a Boltzmann factor exp[ - Φ/2kT] to take care of the average intermolecular potential. We divide here the potential by two because this interaction energy is shared between two particles. Thus:

The total attraction felt by a single particle is:

where we assumed that in a shell of thickness dr there are N/V 4π r2dr particles. This is a mean field approximation; the position of the particles is averaged. In reality the density close to the particle is different than far away as can be described by a pair correlation function. Furthermore, it is neglected that the fluid is enclosed between walls. Performing the integral we get:

Hence, we obtain:

From statistical thermodynamics we know that:

- ,

so that we only have to differentiate the terms containing . We get:

Application to compressible fluids

The equation is also usable as a PVT equation for compressible fluids (e.g. polymers). In this case specific volume changes are small and it can be written in a simplified form:

where p is the pressure, V is specific volume, T is the temperature and A, B, C are parameters.

See also

- Gas laws

- Ideal gas

- Inversion temperature

- Iteration

- Maxwell construction

- Real gas

- Theorem of corresponding states

- Van der Waals constants (data page)

- Redlich–Kwong equation of state

References

- ↑ Epstein, P.S., Textbook of Thermodynamics, John Wiley & Sons, NY, p 9, (1937)

- ↑ Boltzmann, L., Vorlesungen Über Gastheorie; English Translation S.G. Brush, Lectures on Gas Theory, Dover, N.Y. pp 221-231

- ↑ Boltzmann, p 221-224

- ↑ Truesdale, C. and Bharatha, S., Classical Thermodynamics as a Theory of Heat Engines, Springer-Verlag, NY, pp 13-15, (1977)

- ↑ Epstein, p. 11

- ↑ Epstein, p.10

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 van der Waals, J.D., Over de Continuïteit van den Gas en Vloeistoftoestand, Ph.D. Thesis, Leiden Univ. (1873); English Translation J.S. Rowlinson, On the Continuity of the Gaseous and Liquid States, Dover, N.Y. (1988)

- ↑ Epstein, p.10

- ↑ Epstein, P.S., p. 10

- ↑ Boltzmann, L. Enzykl. der Mathem. Wiss., Vol. V. 1, p. 550

- ↑ Sommerfeld, A., Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics Lectures on Theoretical Physics Volume V, Edited by Bopp, F. and Meixner, J., Translated by Kestin, J., Academic Press, N.Y., pp 55, 66, (1956)

- ↑ Sommerfeld, pp. 55-68

- ↑ Goodstein, D.L., States of Matter, Dover, N.Y., pp 443-452, (1975)

- ↑ Lienhard, J.H., The Properties and Behavior of Superheated Liquids, Lat. Am. J. Heat and Mass Transfer, 10, 169-187, (1986)

- ↑ Peck, R.E., The Assimilation of van der Waals Equation in the Corresponding States Family, Can. J. Chem. Eng., 60, 446-449 (1982)

- ↑ Pitzer, K.S., Lippman D.Z., Curl R.F., Huggins C.M. and Peterson D.E., The Volumetric and Thermodynamic Properties of Fluids. II. Compressibility Factor, Vapor Pressure and Entropy of Vaporization, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 77, 3433-3440, (1955)

- ↑ Weinberg, S., Foundations of Modern Physics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., pp 4-5 (2021)

- ↑ Gibbs, J.W. The Collected Works of J. Willard Gibbs Volume II Part One Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, Yale University Press , New Haven, pp vii-xii, (1901 reprinted in 1948)

- ↑ Boltzmann, p 218

- ↑ Andrews, Thomas, The Bakerian Lecture: On the Continuity of the Gaseous and Liquid States of Matter, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, {\bf 159}, pp. 575-590, (1869)

- ↑ Klein, M. J., The Historical Origins of the Van der Waals Equation, Physica, {\bf 73}, p. 31, (1974)

- ↑ Goodstein, D.L., p 450-451

- ↑ Boltzmann, L., p. 232-233

- ↑ Goodstein, D.L., p. 452

- ↑ Lekner, J. Parametric solution of the van der Waals liquid-vapor coexistence curve, Am. J. Phys., 50, 161-163, (1982)

- ↑ Sommerfeld, pp. 56-57

- ↑ Goodstein, p 449

- ↑ Boltzmann, p 237-238

- ↑ Boltzmann, L., pp 239-240

- ↑ Barenblatt, G.I., Scaling, Cambridge University Press, pp 22-26, (2003)

- ↑ Johnston, D.C., Thermodynamic Properties of the van der Waals Fluid, arXiv:1402.1205v1, (2014)

- ↑ Lienhard, J.H., The Properties and Behavior of Superheated Liquids, Lat. Am. J. Heat and Mass Transfer, 10, 169-187, (1986)

- ↑ Dong, W.G., and Lienhard, J.H., Corresponding States Correlation of Saturated and Metastable Properties, Canad J Chem Eng, 64, 159-161, (1986)

- ↑ Whitman, A.M., Thermodynamics: Basic Principles and Engineering Applications, Springer, N.Y., pp 155, 203, 204 (2023)

- ↑ Moran, M.J., and Shapiro, H.N., Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics 4th Edition, pp. 574, 580 (2000)

- ↑ Whitman, p 155

- ↑ Moran and Shapiro, p 574

- ↑ Whitman, p. 203

- ↑ Moran and Shapiro, p. 574

- ↑ Whitman, p. 204

- ↑ Moran and Shapiro, p. 580

- ↑ Callen, H.B., Thermodynamics, John Wiley \& Sons, N.Y., pp 131-135, (1960)

- ↑ Epstein, p 10

- ↑ Callen, pp. 37-44

- ↑ Callen, p. 153

- ↑ Callen, pp. 85-101

- ↑ Callen, pp 146-156

- ↑ Maxwell, J.C. On the Dynamical Evidence of the Molecular Constitution of Bodies, Nature, 11 (279), 357-359, (1875)

- ↑ Shamsundar, N. and Lienhard, J.H., Saturation and Metastable Properties of the van der Waals Fluid, Canad J Chem Eng, 61, 876-880, (1983)

- ↑ Barrufet, M.A., Eubank, P.T., Generalized Saturation Properties of Pure Fluids Via Cubic Equations of State, ASEE Chemical Engineering Education, 168-175, (1989)

- ↑ Lekner, J.

- ↑ Johnston, D.C., Thermodynamic Properties of the van der Waals Fluid, arXiv:1402.1205v1, (2014)

- ↑ Boltzmann, pp. 248-250

- ↑ Lienhard. J.H., Shamsundar, N., and Biney, P.O., Spinodal Lines and Equations of State: A Review, Nuclear Engineering and Design, 95, 297-314, (1986)

- ↑ Tien, C.L., and Lienhard, J.H., Statistical Thermodynamics Revised Printing, Hemisphere Publishing, NY, p.254, (1979)

- ↑ Callen, pp 146-156

- ↑ Sommerfeld, p 66

- ↑ Callen, pp 146-156

- ↑ Rowlinson, p. 22

- ↑ Dong, W.G., and Lienhard, J.H., Corresponding States Correlation of Saturated and Metastable Properties, Canad J Chem Eng, 64, 159-161, (1986)

- ↑ Sommerfeld, pp 61-63

- ↑ Sommerfeld, pp 60-62

- ↑ Sommerfeld, p 61

- ↑ Van Wylen, G.J., and Sonntag, R.E., Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics Second Edition, Wiley, N.Y., p. 49, (1973)

- ↑ Su, G.J., Modified Law of Corresponding States for Real Gases, Ind. Eng. Chem., 38, 803-806, (1946)

- ↑ Moran, M.J., and Shapiro, H.N., p. 113

- ↑ Tien and Lienhard, p. 247-248

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Hewitt, Nigel. "Who was Van der Waals anyway and what has he to do with my Nitrox fill?". Maths for Divers. http://www.nigelhewitt.co.uk/diving/maths/vdw.html.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Lindsey, Brice, "Mixing Rules for Simple Equations of State", Intermolecular Potentials and the Evaluation of Second Virial Coefficient, https://slideplayer.com/slide/9376976/28/images/34/Mixing+Rules+for+Simple+Equations+of+State.jpg, retrieved 1 February 2019

- ↑ van der Waals, Johannes Diderik. "J. D. van der Waals - Nobel lecture". Nobel Prize Outreach. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1910/waals/lecture/.

- ↑ Hill, Terrell L. (1960). An Introduction to Statistical Thermodynamics. Courier Corporation. p. 77.

- ↑ Denker, John (2014). "Chapter 26.9, Derivation: Particle in a Box". Modern Thermodynamics. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1502530356. https://www.av8n.com/physics/thermo/z-particles.html#sec-particle-box. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

Further reading

- Chandler, David (1987). Introduction to Modern Statistical Mechanics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 287–295. ISBN 0195042778.

- Cross, Michael (2004), "Lecture 3: First Order Phase Transitions", Physics 127: Statistical Physics, Second Term, Pasadena, California: Division of Physics, Mathematics, and Astronomy, California Institute of Technology, http://www.pmaweb.caltech.edu/~mcc/Ph127/b/Lecture3.pdf.

- Dalgarno, A.; Davison, W.D. (1966). "The Calculation of Van Der Waals Interactions". Advances in Atomic and Molecular Physics 2: 1–32. doi:10.1016/S0065-2199(08)60216-X. ISBN 9780120038022. Bibcode: 1966AdAMP...2....1D.

- Kittel, Charles; Kroemer, Herbert (1980). Thermal Physics (Revised ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 287–295. ISBN 0716710889.

|