Physics:Vibration of plates

The vibration of plates is a special case of the more general problem of mechanical vibrations. The equations governing the motion of plates are simpler than those for general three-dimensional objects because one of the dimensions of a plate is much smaller than the other two. This permits a two-dimensional plate theory to give an excellent approximation to the actual three-dimensional motion of a plate-like object.[1]

There are several theories that have been developed to describe the motion of plates. The most commonly used are the Kirchhoff-Love theory[2] and the Uflyand-Mindlin.[3][4] The latter theory is discussed in detail by Elishakoff.[5] Solutions to the governing equations predicted by these theories can give us insight into the behavior of plate-like objects both under free and forced conditions. This includes the propagation of waves and the study of standing waves and vibration modes in plates. The topic of plate vibrations is treated in books by Leissa,[6][7] Gontkevich,[8] Rao,[9] Soedel,[10] Yu,[11] Gorman[12][13] and Rao.[14]

Kirchhoff-Love plates

The governing equations for the dynamics of a Kirchhoff-Love plate are

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} N_{\alpha\beta,\beta} & = J_1~\ddot{u}_\alpha \\ M_{\alpha\beta,\alpha\beta} + q(x,t) & = J_1~\ddot{w} - J_3~\ddot{w}_{,\alpha\alpha} \end{align} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ u_\alpha }[/math] are the in-plane displacements of the mid-surface of the plate, [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] is the transverse (out-of-plane) displacement of the mid-surface of the plate, [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] is an applied transverse load pointing to [math]\displaystyle{ x_3 }[/math] (upwards), and the resultant forces and moments are defined as

- [math]\displaystyle{ N_{\alpha\beta} := \int_{-h}^h \sigma_{\alpha\beta}~dx_3 \quad \text{and} \quad M_{\alpha\beta} := \int_{-h}^h x_3~\sigma_{\alpha\beta}~dx_3 \,. }[/math]

Note that the thickness of the plate is [math]\displaystyle{ 2h }[/math] and that the resultants are defined as weighted averages of the in-plane stresses [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_{\alpha\beta} }[/math]. The derivatives in the governing equations are defined as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{u}_i := \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial t} ~;~~ \ddot{u}_i := \frac{\partial^2 u_i}{\partial t^2} ~;~~ u_{i,\alpha} := \frac{\partial u_i}{\partial x_\alpha} ~;~~ u_{i,\alpha\beta} := \frac{\partial^2 u_i}{\partial x_\alpha \partial x_\beta} }[/math]

where the Latin indices go from 1 to 3 while the Greek indices go from 1 to 2. Summation over repeated indices is implied. The [math]\displaystyle{ x_3 }[/math] coordinates is out-of-plane while the coordinates [math]\displaystyle{ x_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ x_2 }[/math] are in plane. For a uniformly thick plate of thickness [math]\displaystyle{ 2h }[/math] and homogeneous mass density [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ J_1 := \int_{-h}^h \rho~dx_3 = 2\rho h \quad \text{and} \quad J_3 := \int_{-h}^h x_3^2~\rho~dx_3 = \frac{2}{3}\rho h^3 \,. }[/math]

Isotropic Kirchhoff–Love plates

For an isotropic and homogeneous plate, the stress-strain relations are

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{bmatrix}\sigma_{11} \\ \sigma_{22} \\ \sigma_{12} \end{bmatrix} = \cfrac{E}{1-\nu^2} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & \nu & 0 \\ \nu & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1-\nu \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}\varepsilon_{11} \\ \varepsilon_{22} \\ \varepsilon_{12} \end{bmatrix} \,. }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_{\alpha\beta} }[/math] are the in-plane strains and [math]\displaystyle{ \nu }[/math] is the Poisson's ratio of the material. The strain-displacement relations for Kirchhoff-Love plates are

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_{\alpha\beta} = \frac{1}{2}(u_{\alpha,\beta}+u_{\beta,\alpha}) - x_3\,w_{,\alpha\beta} \,. }[/math]

Therefore, the resultant moments corresponding to these stresses are

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{bmatrix}M_{11} \\ M_{22} \\ M_{12} \end{bmatrix} = -\cfrac{2h^3E}{3(1-\nu^2)}~\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \nu & 0 \\ \nu & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1-\nu \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} w_{,11} \\ w_{,22} \\ w_{,12} \end{bmatrix} }[/math]

If we ignore the in-plane displacements [math]\displaystyle{ u_{\alpha\beta} }[/math], the governing equations reduce to

- [math]\displaystyle{ D\nabla^2\nabla^2 w = q(x,t) - 2\rho h\ddot{w} \, }[/math]

- where [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math] is the bending stiffness of the plate. For a uniform plate of thickness [math]\displaystyle{ 2h }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ D := \cfrac{2h^3E}{3(1-\nu^2)} \,. }[/math]

The above equation can also be written in an alternative notation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu \Delta\Delta w - \hat{q} + \rho w_{tt}= 0\,. }[/math]

In solid mechanics, a plate is often modeled as a two-dimensional elastic body whose potential energy depends on how it is bent from a planar configuration, rather than how it is stretched (which is the instead the case for a membrane such as a drumhead). In such situations, a vibrating plate can be modeled in a manner analogous to a vibrating drum. However, the resulting partial differential equation for the vertical displacement w of a plate from its equilibrium position is fourth order, involving the square of the Laplacian of w, rather than second order, and its qualitative behavior is fundamentally different from that of the circular membrane drum.

Free vibrations of isotropic plates

For free vibrations, the external force q is zero, and the governing equation of an isotropic plate reduces to

- [math]\displaystyle{ D\nabla^2\nabla^2 w = - 2\rho h\ddot{w} }[/math]

or

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu \Delta\Delta w + \rho w_{tt}= 0\,. }[/math]

This relation can be derived in an alternative manner by considering the curvature of the plate.[15] The potential energy density of a plate depends how the plate is deformed, and so on the mean curvature and Gaussian curvature of the plate. For small deformations, the mean curvature is expressed in terms of w, the vertical displacement of the plate from kinetic equilibrium, as Δw, the Laplacian of w, and the Gaussian curvature is the Monge–Ampère operator wxxwyy−w2xy. The total potential energy of a plate Ω therefore has the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ U = \int_\Omega [(\Delta w)^2 +(1-\mu)(w_{xx}w_{yy}-w_{xy}^2)]\,dx\,dy }[/math]

apart from an overall inessential normalization constant. Here μ is a constant depending on the properties of the material.

The kinetic energy is given by an integral of the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ T = \frac{\rho}{2}\int_\Omega w_t^2\, dx\, dy. }[/math]

Hamilton's principle asserts that w is a stationary point with respect to variations of the total energy T+U. The resulting partial differential equation is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho w_{tt} + \mu \Delta\Delta w = 0.\, }[/math]

Circular plates

For freely vibrating circular plates, [math]\displaystyle{ w = w(r,t) }[/math], and the Laplacian in cylindrical coordinates has the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla^2 w \equiv \frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial }{\partial r}\left(r \frac{\partial w}{\partial r}\right) \,. }[/math]

Therefore, the governing equation for free vibrations of a circular plate of thickness [math]\displaystyle{ 2h }[/math] is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial }{\partial r}\left[r \frac{\partial }{\partial r}\left\{\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial }{\partial r}\left(r \frac{\partial w}{\partial r}\right)\right\}\right] = -\frac{2\rho h}{D}\frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial t^2}\,. }[/math]

Expanded out,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial^4 w}{\partial r^4} + \frac{2}{r} \frac{\partial^3 w}{\partial r^3} - \frac{1}{r^2} \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial r^2} + \frac{1}{r^3} \frac{\partial w}{\partial r} = -\frac{2\rho h}{D}\frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial t^2}\,. }[/math]

To solve this equation we use the idea of separation of variables and assume a solution of the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ w(r,t) = W(r)F(t) \,. }[/math]

Plugging this assumed solution into the governing equation gives us

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{\beta W}\left[\frac{d^4 W}{dr^4} + \frac{2}{r}\frac{d^3 W}{dr^3} - \frac{1}{r^2}\frac{d^2W}{dr^2} + \frac{1}{r^3} \frac{d W}{dr}\right] = -\frac{1}{F}\cfrac{d^2 F}{d t^2} = \omega^2 }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \omega^2 }[/math] is a constant and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta := 2\rho h/D }[/math]. The solution of the right hand equation is

- [math]\displaystyle{ F(t) = \text{Re}[ A e^{i\omega t} + B e^{-i\omega t}] \,. }[/math]

The left hand side equation can be written as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{d^4 W}{dr^4} + \frac{2}{r}\frac{d^3 W}{dr^3} - \frac{1}{r^2}\frac{d^2W}{dr^2} + \frac{1}{r^3} \cfrac{d W}{d r} = \lambda^4 W }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda^4 := \beta\omega^2 }[/math]. The general solution of this eigenvalue problem that is appropriate for plates has the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ W(r) = C_1 J_0(\lambda r) + C_2 I_0(\lambda r) }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ J_0 }[/math] is the order 0 Bessel function of the first kind and [math]\displaystyle{ I_0 }[/math] is the order 0 modified Bessel function of the first kind. The constants [math]\displaystyle{ C_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ C_2 }[/math] are determined from the boundary conditions. For a plate of radius [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] with a clamped circumference, the boundary conditions are

- [math]\displaystyle{ W(r) = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \cfrac{d W}{d r} = 0 \quad \text{at} \quad r = a \,. }[/math]

From these boundary conditions we find that

- [math]\displaystyle{ J_0(\lambda a)I_1(\lambda a) + I_0(\lambda a)J_1(\lambda a) = 0 \,. }[/math]

We can solve this equation for [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda_n }[/math] (and there are an infinite number of roots) and from that find the modal frequencies [math]\displaystyle{ \omega_n = \lambda_n^2/\sqrt{\beta} }[/math]. We can also express the displacement in the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ w(r,t) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty C_n\left[J_0(\lambda_n r) - \frac{J_0(\lambda_n a)}{I_0(\lambda_n a)}I_0(\lambda_n r)\right] [A_n e^{i\omega_n t} + B_n e^{-i\omega_n t}] \,. }[/math]

For a given frequency [math]\displaystyle{ \omega_n }[/math] the first term inside the sum in the above equation gives the mode shape. We can find the value of [math]\displaystyle{ C_n }[/math] using the appropriate boundary condition at [math]\displaystyle{ r = 0 }[/math] and the coefficients [math]\displaystyle{ A_n }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B_n }[/math] from the initial conditions by taking advantage of the orthogonality of Fourier components.

Rectangular plates

Consider a rectangular plate which has dimensions [math]\displaystyle{ a\times b }[/math] in the [math]\displaystyle{ (x_1,x_2) }[/math]-plane and thickness [math]\displaystyle{ 2h }[/math] in the [math]\displaystyle{ x_3 }[/math]-direction. We seek to find the free vibration modes of the plate.

Assume a displacement field of the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ w(x_1,x_2,t) = W(x_1,x_2) F(t) \,. }[/math]

Then,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla^2\nabla^2 w = w_{,1111} + 2w_{,1212} + w_{,2222} = \left[\frac{\partial^4 W}{\partial x_1^4} + 2\frac{\partial^4 W}{\partial x_1^2 \partial x_2^2} + \frac{\partial^4W}{\partial x_2^4}\right] F(t) }[/math]

and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ddot{w} = W(x_1,x_2)\frac{d^2F}{dt^2} \,. }[/math]

Plugging these into the governing equation gives

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{D}{2\rho h W}\left[\frac{\partial^4 W}{\partial x_1^4} + 2\frac{\partial^4 W}{\partial x_1^2 \partial x_2^2} + \frac{\partial^4W}{\partial x_2^4}\right] = -\frac{1}{F}\frac{d^2F}{dt^2} = \omega^2 }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \omega^2 }[/math] is a constant because the left hand side is independent of [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] while the right hand side is independent of [math]\displaystyle{ x_1,x_2 }[/math]. From the right hand side, we then have

- [math]\displaystyle{ F(t) = A e^{i\omega t} + B e^{-i\omega t} \,. }[/math]

From the left hand side,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial^4 W}{\partial x_1^4} + 2\frac{\partial^4 W}{\partial x_1^2 \partial x_2^2} + \frac{\partial^4W}{\partial x_2^4} = \frac{2\rho h \omega^2}{D} W =: \lambda^4 W }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda^2 = \omega\sqrt{\frac{2\rho h}{D}} \,. }[/math]

Since the above equation is a biharmonic eigenvalue problem, we look for Fourier expansion solutions of the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ W_{mn}(x_1,x_2) = \sin\frac{m\pi x_1}{a}\sin\frac{n\pi x_2}{b} \,. }[/math]

We can check and see that this solution satisfies the boundary conditions for a freely vibrating rectangular plate with simply supported edges:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} w(x_1,x_2,t) = 0 & \quad \text{at}\quad x_1 = 0, a \quad \text{and} \quad x_2 = 0, b \\ M_{11} = D\left(\frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial x_1^2} + \nu\frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial x_2^2}\right) = 0 & \quad \text{at}\quad x_1 = 0, a \\ M_{22} = D\left(\frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial x_2^2} + \nu\frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial x_1^2}\right) = 0 & \quad \text{at}\quad x_2 = 0, b \,. \end{align} }[/math]

Plugging the solution into the biharmonic equation gives us

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda^2 = \pi^2\left(\frac{m^2}{a^2} + \frac{n^2}{b^2}\right) \,. }[/math]

Comparison with the previous expression for [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda^2 }[/math] indicates that we can have an infinite number of solutions with

- [math]\displaystyle{ \omega_{mn} = \left(\frac{m^2}{a^2} + \frac{n^2}{b^2}\right)\sqrt{\frac{D\pi^4}{2\rho h}} \,. }[/math]

Therefore the general solution for the plate equation is

- [math]\displaystyle{ w(x_1,x_2,t) = \sum_{m=1}^\infty \sum_{n=1}^\infty \sin\frac{m\pi x_1}{a}\sin\frac{n\pi x_2}{b} \left( A_{mn} e^{i\omega_{mn} t} + B_{mn} e^{-i\omega_{mn} t}\right) \,. }[/math]

To find the values of [math]\displaystyle{ A_{mn} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B_{mn} }[/math] we use initial conditions and the orthogonality of Fourier components. For example, if

- [math]\displaystyle{ w(x_1,x_2,0) = \varphi(x_1,x_2) \quad \text{on} \quad x_1 \in [0,a] \quad \text{and} \quad \frac{\partial w}{\partial t}(x_1,x_2,0) = \psi(x_1,x_2)\quad \text{on} \quad x_2 \in [0,b] }[/math]

we get,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} A_{mn} & = \frac{4}{ab}\int_0^a \int_0^b \varphi(x_1,x_2) \sin\frac{m\pi x_1}{a}\sin\frac{n\pi x_2}{b} dx_1 dx_2 \\ B_{mn} & = \frac{4}{ab\omega_{mn}}\int_0^a \int_0^b \psi(x_1,x_2) \sin\frac{m\pi x_1}{a}\sin\frac{n\pi x_2}{b} dx_1 dx_2\,. \end{align} }[/math]

References

- ↑ Reddy, J. N., 2007, Theory and analysis of elastic plates and shells, CRC Press, Taylor and Francis.

- ↑ A. E. H. Love, On the small free vibrations and deformations of elastic shells, Philosophical trans. of the Royal Society (London), 1888, Vol. série A, N° 17 p. 491–549.

- ↑ Uflyand, Ya. S.,1948, Wave Propagation by Transverse Vibrations of Beams and Plates, PMM: Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics, Vol. 12,pp. 287-300 (in Russian)

- ↑ Mindlin, R.D. 1951, Influence of rotatory inertia and shear on flexural motions of isotropic, elastic plates, ASME Journal of Applied Mechanics, Vol. 18 pp. 31–38

- ↑ Elishakoff ,I.,2020, Handbook on Timoshenko-Ehrenfest Beam and Uflyand-Mindlin Plate Theories, World Scientific, Singapore, ISBN:978-981-3236-51-6

- ↑ Leissa, A.W.,1969, Vibration of Plates, NASA SP-160, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office

- ↑ Leissa, A.W. and Qatu, M.S.,2011, Vibration of Continuous Systems, New York: Mc Graw-Hill

- ↑ Gontkevich, V. S., 1964, Natural Vibrations of Plates and Shells, Kiev: “Naukova Dumka” Publishers, 1964 (in Russian); (English Translation: Lockheed Missiles & Space Co., Sunnyvale, CA)

- ↑ Rao, S.S., Vibration of Continuous Systems, New York: Wiley

- ↑ Soedel, W.,1993, Vibrations of Shells and Plates, New York: Marcel Dekker Inc., (second edition)

- ↑ Yu, Y.Y.,1996, Vibrations of Elastic Plates, New York: Springer

- ↑ Gorman, D.,1982, Free Vibration Analysis of Rectangular Plates, Amsterdam: Elsevier

- ↑ Gorman, D.J.,1999, Vibration Analysis of Plates by Superposition Method, Singapore: World Scientific

- ↑ Rao, J.S.,1999, Dynamics of Plates, New Delhi: Narosa Publishing House

- ↑ Courant, Richard; Hilbert, David (1953), Methods of mathematical physics. Vol. I, Interscience Publishers, Inc., New York, N.Y.

See also

- Bending

- Bending of plates

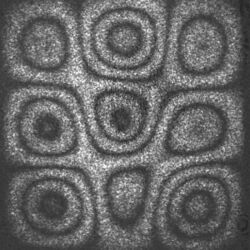

- Chladni figures

- Infinitesimal strain theory

- Kirchhoff–Love plate theory

- Linear elasticity

- Mindlin–Reissner plate theory

- Plate theory

- Stress (mechanics)

- Stress resultants

- Structural acoustics

|