Place:Royal necropolis of Byblos

| Royal necropolis of Byblos | |

|---|---|

Promontory of Byblos. The royal necropolis lies at the base of the Roman colonnade. | |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 34°07′10″N 35°38′43″E / 34.11944°N 35.64528°E |

| Founded | 19th century BC |

| Built for | Resting place of the Phoenician Gebalite rulers |

| Architectural style(s) | Ancient Egypt–inspired, Phoenician |

| Governing body | Lebanese Directorate General of Antiquities[1] |

| <mapframe zoom="10" frameless="1" align="center" longitude="35.645277777778" latitude="34.119444444444" height="200" width="270">{"type":"Feature","geometry":{"coordinates":[35.64527777777778,34.11944444444445],"type":"Point"},"properties":{"title":"Royal necropolis of Byblos","marker-color":"#5E74F3"}}</mapframe> | |

The royal necropolis of Byblos is a group of nine Bronze Age underground shaft and chamber tombs housing the sarcophagi of several kings of the city. Byblos (modern Jbeil) is a coastal city in Lebanon, and one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world. The city established major trade links with Egypt during the Bronze Age, resulting in a heavy Egyptian influence on local culture and funerary practices. The location of ancient Byblos was lost to history, but was rediscovered in the late 19th century by the French biblical scholar and Orientalist Ernest Renan. The remains of the ancient city sat on top of a hill in the immediate vicinity of the modern city of Jbeil. Exploratory trenches and minor digs were undertaken by the French mandate authorities, during which reliefs inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs were excavated. The discovery stirred the interest of western scholars, leading to systematic surveys of the site.

On 16 February 1922, heavy rains triggered a landslide in the seaside cliff of Jbeil, exposing an underground tomb containing a massive stone sarcophagus. The grave was explored by the French epigrapher and archeologist Charles Virolleaud. Intensive digs were carried out around the site of the tomb by the French Egyptologist Pierre Montet, who unearthed eight additional shaft and chamber tombs. Each of the tombs consisted of a vertical shaft connected to a horizontal burial chamber at its bottom. Montet categorized the graves into two groups. The tombs of the first group date back to the Middle Bronze Age, specifically the 19th century BC; some were unspoiled, and contained a multitude of often valuable items, including royal gifts from Middle Kingdom pharaohs Amenemhat III and Amenemhat IV, locally made Egyptian-style jewelry, and various serving vessels. The graves of the second group were all robbed in antiquity, making precise dating problematic, but the artifacts indicate that some of the tombs were used into the Late Bronze Age (16th to 11th centuries BC).

In addition to grave goods, seven stone sarcophagi were discovered—the burial chambers that did not contain stone sarcophagi appear to have housed wooden ones which disintegrated over time. The stone sarcophagi were undecorated, save the Ahiram sarcophagus. This sarcophagus is famed for its Phoenician inscription, one of five epigraphs known as the Byblian royal inscriptions; it is considered to be the earliest known example of the fully developed Phoenician alphabet. Montet compared the function of the Byblos tombs to that of Egyptian mastabas, where the soul of the deceased was believed to fly from the burial chamber, through the funerary shaft, to the ground-level chapel where priests would officiate.

Historical background

Byblos (Jbeil) is one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world. It has taken many names over the ages; it appears as Kebny in 4th-dynasty Egyptian hieroglyphic records, and as Gubla (𒁺𒆷) in the Akkadian cuneiform Amarna letters of 18th-dynasty-Egypt.[2][3][4] In the second millennium BC, its name appeared in Phoenician inscriptions, such as the Ahiram sarcophagus epitaph, as Gebal (𐤂𐤁𐤋, GBL),[5][6][7] which derives from GB (𐤂𐤁, "well"), and ʾL (𐤀𐤋, "god"). The name thus seems to have meant the "Well of the God".[8] Another interpretation of the name Gebal is "mountain town", derived from the Canaanite Gubal.[9] "Byblos" is a much later Greek exonym, possibly a corruption of Gebal.[9] The ancient settlement sat on a plateau immediately abutting the sea that has been continuously inhabited since as early as 7000–8000 BC.[10] Simple, circular and rectangular habitation units and jar burials dating from the Chalcolithic were unearthed in Byblos. The village grew during the Bronze Age, and became a major center for trade with Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Crete, and Egypt.[11][12]

Egypt sought to maintain favourable relations with Byblos because of its need for lumber, abundant in the mountains of Lebanon.[11][13][14] During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2686 BC–c. 2181 BC), Byblos was under the Egyptian sphere of influence. The city was destroyed by the Amorites around 2150 BC, in the aftermath of the power vacuum that ensued after the fall of the Old Kingdom.[11][12] However, with the emergence of Egypt's Middle Kingdom (c. 1991 BC–c. 1778 BC), Byblos' defensive walls and temples were rebuilt, and it came once more allied to Egypt.[11][12] In 1725 BC, Egypt's Nile Delta and the coastal cities of Phoenicia fell to the Hyksos as the Middle Kingdom disintegrated. A century and a half later, Egypt expelled the Hyksos and returned Phoenicia under its fold, and effectively defended it against the Mitanni and Hittite invasions.[11][12] During this period, Gebalite[lower-alpha 1] trade flourished, and the first phonetic alphabet was developed in Byblos.[12] It consisted of 22 consonant graphemes that were simple enough for common traders to use.[12][17][18]

Relations with Egypt dwindled again in the mid 14th–century, as attested in the Amarna correspondence with the Gebalite king Rib-Hadda. The letters reveal the inability of Egypt to defend Byblos and its territories against Hittite incursion.[11][12][19] During the time of Ramses II, Egyptian hegemony over Byblos was restored; nevertheless, the city was destroyed soon after by the Sea Peoples around 1195 BC. Egypt was weakened during this time, and consequently, Phoenicia experienced a period of prosperity and independence. The Story of Wenamun, which is contemporaneous to this period, shows the continued, yet tepid relations between the Gebalite ruler and the Egyptians.[11]

Longstanding relations with Egypt heavily influenced local culture and funerary practices. It is during the period of Egyptian overlordship that the practice of Egypt-inspired shaft burials appeared.[20]

Excavation history

The search for the ancient city

Ancient texts and manuscripts hinted at the location of Gebal, which was lost to history until its rediscovery in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1860, French biblical scholar and orientalist Ernest Renan carried out an archeological mission in Lebanon and Syria during the French expedition in the area. Renan had relied on ancient Greek historian and geographer Strabo's writing in his attempt to locate the city. Strabo identified Byblos as a city situated on a hill some distance away from the sea.[lower-alpha 2][23][21] This description misled scholars, including Renan who thought that the city lay in the neighboring Qassouba (Kassouba), but he concluded that this hill was too small to have housed a grand ancient city.[24][25]

Renan correctly posited that the ancient Byblos must have been located atop the circular hill dominated by the Crusader citadel of Jbeil, at the immediate outskirts of the modern city. He based his assumption on the reverse of a Roman Elagabalus-era coin depicting a representation of the city with a river running at its feet,[lower-alpha 3][25][24] and theorized that the river in question was the stream that skirts the citadel hill. Starting from the citadel, he had two long trenches dug; the trenches revealed ancient artifacts unquestionably demonstrating that Jbeil is the same as the ancient city of Gebal/Byblos.[23][25]

Early archeological works

During the period of the French Mandate, High Commissioner General Henri Gouraud established the Service of Antiquities in Lebanon; he appointed French archeologist Joseph Chamonard to head the newly created service. Chamonard was succeeded by French epigrapher and archeologist Charles Virolleaud as of 1 October 1920. The service prioritized archeological surveys in the town of Jbeil where Renan had found ancient remains.[26]

On 16 March 1921, Pierre Montet, the Egyptology professor at the University of Strasbourg, addressed a letter to notable French archeologist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau describing Egyptian-inscribed reliefs he had discovered during a 1919 archeological mission in Jbeil. The fascinated Clermont-Ganneau personally funded the methodological survey of the site, which he believed contained an Egyptian temple. Montet was selected to head the excavations, he arrived at Beirut on 17 October 1921.[27][28] Excavation works in Jbeil were inaugurated on 20 October 1921 by the French mandate authorities, they consisted of annual campaigns of three months each.[29]

Discovery of the royal necropolis

On 16 February 1922, heavy rain triggered a landslide on the seaside cliff of Jbeil which exposed an underground man-made cavity. The next day the administrative advisor of Mount Lebanon informed the Service of Antiquities of the landslide and announced the discovery of an ancient underground tomb containing a large unopened sarcophagus.[30][31] To keep treasure hunters at bay, the perimeter was secured by the Mudir of Jbeil Sheikh Wadih Hobeiche.[32] Virolleaud arrived at the site to clear and make an inventory of the contents of the unearthed tomb;[31] he continued to supervise the digs and opened the discovered sarcophagus on 26 February 1922.[33] A second tomb (named Tomb II) was discovered by Montet in October 1923;[34] the discovery triggered a systematic survey of the surrounding area in autumn 1923.[35] Montet headed the excavation of ancient Byblos until 1924; during this period, he uncovered seven other tombs, bringing the total number to nine.[11] French archeologist Maurice Dunand succeeded Montet in 1925 and continued his predecessor's work on the archeological tell for another forty years.[11]

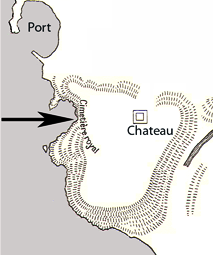

Location

Located 33 km (21 mi) north of Beirut,[36] ancient Byblos/Gebal (modern name: Jbeil/Gebeil) lays south of the city's medieval center. It sits on a seaside promontory consisting of two hills separated by a dell. A 22 m (72 ft) deep well provided the settlement with freshwater.[37] The highly defensible archeological tell of Byblos is flanked by two harbors that were used for sea trade.[37] The royal necropolis of Byblos is a semicircular burial ground located on the promontory summit, on a spur overlooking both seaports of the city, within the walls of ancient Byblos.[38][39]

Description

Montet assigned numbers to the royal tombs and categorized them into two groups: the first, northern group included tombs I to IV; these were of an older construction date and were meticulously built. Tomb III and IV had been emptied of their contents by ancient looters, while the other two remained undisturbed.[40][41]

The second group of tombs is located at the southern side of the necropolis, it includes tombs V to IX. Tombs V to VIII were of inferior construction quality compared to northern ones, and were dug in clay instead of rock at a later period of time.[40][42] Only Tomb IX retained evidence of careful construction reminiscent of the earlier tombs. Earthenware fragments discovered in this tomb, bearing the name of Abishemu in Egyptian hieroglyphs, suggest that its construction date was closer to that of the northern group. Ancient looters had broken into all the tombs of the second group.[40][41][43]

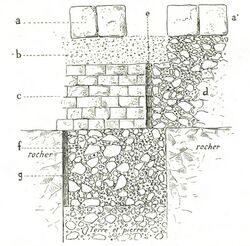

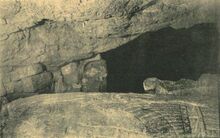

Tombs I and II

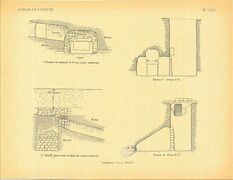

Tomb I consists of a 4 m (13 ft) wide by 12 m (39 ft) deep square vertical shaft giving access to an underground burial chamber carved partly from solid rock and partly from clay.[lower-alpha 4] The west wall, which isolated it from the exterior seaside cliff, had collapsed during the 1922 landslide. The grave goods were not affected by the landslide; inside the burial chamber the excavators discovered several pottery jars in the damp clay, and a large white limestone sarcophagus with three protruding lugs on its lid by which it could be manipulated.[44]

The sarcophagus was placed in a north–south orientation.[45][32] A rock-cut opening is present at a height of 1 m (3.3 ft) on the north wall of Tomb I's chamber, directly facing the sarcophagus. The opening leads to a 1.8 m (5.9 ft) high and 1.2 m (3.9 ft) to 1.5 m (4.9 ft) wide corridor that joins the south side of the shaft of Tomb II. The same corridor is joined by a passageway emerging from the northwestern angle of Tomb I's shaft. Midway between Tomb I and the shaft of Tomb II the S-shaped corridor opens, to its north side, onto a small nondescript hole giving access to a roughly cut round cavity housing an archaic tomb.[45]

A coarsely built wall separated the chamber of Tomb I from its shaft. The shaft was filled to its brim with stones and mortar. The same material was used to build a platform around the shaft, on top of which were laid the foundations of a mastaba-like building. Little remains of the Egyptian-inspired structure because it was replaced by a Roman period bath. Unlike the shaft of Tomb I, the shaft of Tomb II was not closed off with stones and cement, but simply with earth. A thick slab of five to six rows of blocks covered the shaft opening and provided a foundation for a construction from which only a few masonry blocks remain.[46]

The shaft of Tomb II is shallower than that of Tomb I; a single course wall separated it from the burial chamber. Tomb II did not contain any burial receptacles upon its discovery. A number of pottery jars and other artifacts sank in a thick layer of clay, with some of the jars damaged by falling rock fragments from the chamber's ceiling. The ceiling of Tomb II's burial chamber is 3.5 m (11 ft) high at the center of the room, it slopes down to a height of only 1 m (3.3 ft) at its northern wall.[47] Four stones were found at the center of the chamber, they supported a wooden coffin that had disintegrated, leaving rich grave goods scattered in the clay.[34]

Montet demonstrated that Tombs I and II were not broken into before their discovery in 1922–1923, contrary to what his predecessor Virolleaud reported.[48] Virolleaud had found shards of glass lodged in the Tomb I chamber wall and assumed they dated from Roman times.[lower-alpha 5][32]

Tombs III and IV

The shafts of Tombs III and IV are located west of Tombs I and II, adjacent to the northern wall of the Roman baths. The shaft opening of Tomb III measures 2.5 m × 3.3 m (8.2 ft × 10.8 ft); it was covered by a heavy layer of cement covering a masonry course sealed with ash, and vertically pierced close to its south-west angle by a square 30 cm (12 in) conduit reminiscent in function to that of Egyptian mastabas' serdabs. Another similarly sized and shaped conduit traversed the deeper layer of shaft filling, but this one flanked the northwest angle of the shaft, and only ran to a depth of 2 m (6.6 ft). The two conduits did not connect. A niche was carved in the north wall close to the bottom of the shaft.[49][50]

Tomb III's burial chamber extends from the southern wall of the shaft, it was closed off by an uncemented single course wall. It is of fine construction with a paved floor and walls carved straight up to the ceiling.[51] Tomb III did not contain a stone sarcophagus, a number of funerary goods were found lying in a 70 cm (28 in) layer of clay.[52]

Tomb IV is located to the east of Tomb III; at 5.75 m (18.9 ft) it is the shallowest of all the necropolis tombs. The shaft measures 3.05 m × 3.95 m (10.0 ft × 13.0 ft); its southern wall was covered by a 1 m (3.3 ft) thick masonry wall and the burial chamber seemed undisturbed, but the excavators found that the limestone sarcophagus was opened and emptied.[53] A vertical conduit, similar to the one found in Tomb III was found in Tomb IV.[52] These conduits appear to have been a distinguishing element of the Byblos funerary cult.[40] The sarcophagus of Tomb IV lay at the center of the burial chamber facing the entryway, similar to all the other sarcophagi found in the surveyed tombs of the necropolis. The builders placed two stones at the base of the sarcophagus to support and level it on the sloping floor.[53]

Tomb V (King Ahiram's Tomb)

The semicircular shape of Tomb V, known as King Ahiram's tomb, is unique within the necropolis. It was found half-filled with mud, with three tombs inside; a large plain one close to the wall, the finely-carved Ahiram sarcophagus at the center, and a smaller plain sarcophagus.[55] It was also the only tomb to have an inscription within its shaft. This Phoenician inscription, dubbed the Byblos Necropolis graffito, is found at a depth of 3 m (9.8 ft) on the south wall of the shaft; it warns looters from entering the grave.[56] French epigrapher René Dussaud interpreted the inscription as "Avis, voici ta perte (est) ci-dessous" [Beware, here is your loss (is) below].[57][58][59]

The shaft of Ahiram's tomb is located midway between the northern tombs group (Tombs I, II, III, and IV) and the southern group (Tombs VI, VII, VIII, and IX). It is flanked on the west by a two course wall and column bases that were part of the tomb's superstructure. The soil on top of the shaft was very compacted; a conduit similar to the ones found in tombs III and IV measuring 2 m (6.6 ft) was found in the northeast corner of the shaft. Molded fragments and marble plates, and numerous shards of pottery, which were markedly different from the ceramic fragments collected in the other tombs, were mixed with the earth used to fill the shaft. Two levels of four square slots are carved at depths of 2.2 m (7.2 ft) and 4.35 m (14.3 ft) respectively on both of the shaft's east and west walls. These four rows of slots used to hold two rows of wooden vertical beams and floors spanning the width of the shaft.[56] According to Montet, the builders of the tomb did not consider that the king's corpse was sufficiently protected by the shaft's surface paving slabs and by the wall built at the entrance to the chamber halfway up the shaft , so they laid wooden beams which acted as a third obstacle. The looters however, removed the paving and dug out the wooden structures; as they emptied the shaft, they could not have missed seeing the warning spell on their way down to the royal grave.[59]

Below the beam slots no additional pottery shards were found, but near the bottom, against the eastward entrance to the burial chamber, several fragments of alabaster vases that had been cast out of the chamber had collected.[59][60] One of these fragments bore the name of Ramses II. The excavators found that the wall that closed off the burial chamber had partly collapsed, and the content of the room was disorderly and half-filled with muddy clay. A huge block of rock, fallen from the vault, rested atop the decorated sarcophagus of Ahiram that occupied the center of the chamber. All of the three chamber sarcophagi were looted and only contained human bones.[61]

Tombs VI, VII, VIII, and IX

File:Historic monuments, Byblos - UNESCO - PHOTO0000002590 0001.tiff This group of tombs is located 50 m (160 ft) east of the necropolis cliffside and 30 m (98 ft) south of shaft IV; they are built in a part of the hill with a heavy sedimentary deposit. The shafts of these tombs are less well-preserved than the shafts of the first group. The shaft of Tomb VIII was still covered with a layer of pavement, while Tombs VI and VII had lost most of their surface cover. The burial chambers of Tombs VI, VII, VIII, and IX are completely dug in muddy soil.[63] Grave robbers were able to burrow from one tomb to the next through the soft clay.[64]

The shaft of Tomb VI is the deepest of the all the necropolis' shafts. An ashlar wall supported the shaft down to a depth of 6 m (20 ft); beyond this depth the shaft continues through the muddy soil, without any masonry retaining wall.[64] Like the rest of this tomb group, Tomb VI was robbed of its content except for a few artifacts that lay in, and at the entrance of the chamber. There were no stone sarcophagi in this tomb.[63]

Tomb VII has the largest of the burial shafts, with sides measuring 5 m (16 ft) each. The chamber of Tomb VII was dug like that of Tomb VI through hard rock and the underlying clay, and was found two-thirds filled with clay and pebbles. At the time of its excavation, the cambered lid of a stone sarcophagus rose through the layer of clay. The stone sarcophagus laid on a layer of stone pavement, and courses of stone that were in a relatively good state of conservation supported the walls of the chamber. The body of the sarcophagus of Tomb VII is roughly cut and is of simple rectangular shape. Two large lugs jut from each of the extremities of the concave lid that, like those of the sarcophagus of Tomb I, were used to manipulate the heavy cover. This tomb contained a good number of precious artifacts and jewels that appear to have been missed by looters.[65]

Tomb VIII is characterized by a rhomboid shaped opening, which evens into a square at the bottom. The thin wall separating Tomb VIII from Tomb VI is perforated in its center, and Montet assumed that it was due to a quarrying accident. The shaft also reaches the layer of clay underlying the hard rock upper layer, and the tomb chamber was found filled with clay and gravel. The chamber had retaining walls, most of which had collapsed, and small pebbles covered the floor. A simple stone sarcophagus, a few fragments of alabaster vases, and other earthenware items were found in the tomb. No precious artifacts were recovered, except for gold foils that were mixed with the tomb's muddy soil.[66]

The shaft of Tomb IX cuts through 8 m (26 ft) of rock. The wall closing off the chamber was not broken into, the looters had burrowed instead through the clay layer to access the chambers of Tomb V, VIII, and IX. The roof of Tomb IX had collapsed, and it was found filled to its brim with mud and ceiling rock shards. The chamber floor was covered by paving stones, and its walls were sturdy and in good condition. The looters almost completely emptied the contents of the tomb except for alabaster, malachite, and pottery receptacle fragments. Among the finds were terracotta artifacts bearing the names of two Gebalite kings, Abi (possibly a name contraction) and Abishemu.[67]

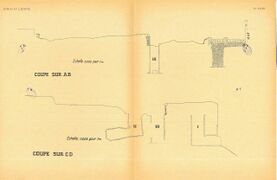

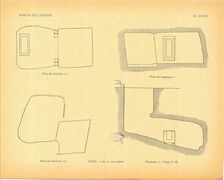

- Montet's sketches of the royal tombs

Context plan of tombs I and II

Section view of tombs I and II

Finds

Sarcophagi

In total, seven stone sarcophagi were discovered in the royal necropolis of Byblos; a single sarcophagus in each of tombs I, IV, VII, VIII and three in Ahiram's tomb (Tomb V).[68][69] The other burial chambers are believed to have housed wooden caskets that have disintegrated over time.[68][69] Tomb II housed a wooden casket that has rotted away, leaving a wealth of objects laying on the burial chamber floor.[70]

The stone sarcophagi found in tombs I and IV are of fine white limestone sourced from the nearby Lebanese mountains; the walls of both sarcophagi are thick, well-polished, and undecorated.[33] Moreover, the sarcophagi found in tombs I, IV, V, and VII share the same morphology which resembles the common stone sarcophagi of Egypt. One difference however, is that the lids of these Gebalite sarcophagi retain the lid lugs which allowed workmen to maneuver them.[71][45][32] These features, along with a number of tomb contents including similarly shaped alabaster containers, suggest that the entire group can be attributed to a restricted time period.[40]

The sarcophagus of Tomb I measures 1.48 m × 2.82 m (4.9 ft × 9.3 ft), and is 1.68 m (5.5 ft) tall.[lower-alpha 6][33] The side walls of the sarcophagus are 35 cm (14 in) thick; the bottom of the sarcophagus body is 44 cm (17 in) thick.[32] The rim of the Sarcophagus I lid is beveled; it is cut from below so as to enter a few centimeters into the sarcophagus body. The back of the lid is rounded and striated with lengthwise irregularly sized flutes. The central flute is the widest; it is flanked by five successively smaller flutes on each side.[72] Three lugs protrude obliquely from the lid's exterior close to its corners; the lug at the northwestern corner and an entire corner section of the lid have broken off at the foot of the sarcophagus. The sarcophagus was opened on 26 February 1922.[33][73]

The sarcophagus of Tomb IV measures 1.41 m × 3 m (4.6 ft × 9.8 ft) and is 1.49 m (4.9 ft) tall. The body of the sarcophagus is slightly more sophisticated as both of its long sides are beveled at the top and bottom. The small sides have a bench-like protrusion at the base. Montet ascertained that the sarcophagus never had a stone lid; he found blackish traces on the rim of the sarcophagus body that prove that it was covered by a curved wooden lid.[74]

The sarcophagi of tombs IV, V and VII were extracted during the fifth campaign, which lasted from 8 March 1926 until 26 June 1926.[75]

The Ahiram sarcophagus

The sandstone sarcophagus of Ahiram was found in Tomb V and is so called for its bas-relief carvings, and its Phoenician inscription that attributes it to King Ahiram. The inscription with 38 words is one of five known Byblian royal inscriptions. It is written in Old Phoenician dialect, and is considered to be the earliest known example of the fully developed Phoenician alphabet discovered to date.[76] For some scholars, the Ahiram sarcophagus inscription represents the terminus post quem of the transmission of the alphabet to Europe.[76] The sarcophagus measures 3 m (9.8 ft) long by 1.14 m (3.7 ft) wide and is 1.47 m (4.8 ft) tall, lid included.[77]

The top of the sarcophagus body is ringed by a frieze of inverted lotus flowers. The flowers alternate between closed buds and open flowers. A motif of thick rope frames the top of the main bas-relief scene, and corner pillars decorate all four sides of the sarcophagus.[78] The body of the sarcophagus rests on four lions on all four sides. The heads and front legs of the lions protrude outside the sarcophagus tank, while the rest of the lions' bodies appear in bas-relief on the long sides.[78]

The main scene on the front of the sarcophagus depicts the king on a throne holding a wilted lotus flower. A table full of offerings stands in front of the throne, followed by a procession of seven male figures.[79] Two scenes of a funerary procession of four mourning women occupy the two small sides of the sarcophagus. Two of the women on each of the sides bare their chests, and the two others are depicted hitting their heads with their hands.[79] The scene on the back side of the sarcophagus shows a procession of men and women bearing offerings.[80]

The lid of the sarcophagus is slightly convex, like those of the neighboring sarcophagi. It has only one lug at each end, which are shaped like lion heads. The bodies of the lions are carved in bas-relief on the flat part of the lid. Two bearded effigies measuring 171 cm (5.61 ft) each are carved on either side of the lions; one of the figures bears a wilted lotus flower, the other a live one. Montet posited that they both represent the deceased king.[78] Lebanese archeologist and museum curator Maurice Chehab, who later demonstrated the presence of traces of red paint on the sarcophagus, interpreted the two figures as the deceased king and his son.[81]

The sarcophagus inscription is composed of 38 words distributed in two parts,[82][83] the shortest of which is found on the sarcophagus body, in the space of the narrow band above the row of lotus flowers.[83] The longer inscription is carved on the front, long edge of the lid.[84] The inscription is cautionary and conjures calamities on whoever desecrates the tomb.[85]

Grave goods

More than 260 items were recovered from the royal necropolis of Byblos.[lower-alpha 7][87]

Egyptian royal gifts

Tomb I contained a 12 cm (4.7 in) high obsidian vase and lid set with gold, engraved with the enthronement name of Amenemhat III in hieroglyphic characters.[88] The same grave also produced two alabaster vases.[89]

Two royal Egyptian gifts were found in Tomb II. The first is a rectangular, 45 cm (18 in) long obsidian box and lid set with gold. The box rests on four legs, and its lid bears a perfectly preserved Egyptian hieroglyphic cartouche containing the enthronement name and epithets of Amenemhat IV.[lower-alpha 8][91] It is not clear what the contents of the box may have been; similarly shaped receptacles were often depicted on Egyptian tomb friezes and called "pr 'nti" which translate to "house of incense".[90] The second gift is a stone vase carved with the name of Amenemhat IV; the cartouche reads: "Long live The Good God, son of Ra, Amenemhat, living forever".[90]

Jewelry and precious objects

The tombs contained a wealth of royal jewelry made from gold, silver and gemstones, some of which bear a heavy Egyptian influence. Each of tombs I, II and III contained chiseled gold Egyptian-influenced pectorals. Tomb II contained an Egyptian-style, locally produced gem-encrusted gold pectoral with its chain and a shell-shaped cloisonné pendant bearing the name of King Ip-Shemu-Abi. Two grand silver hand mirrors were recovered in tombs I and II; all of the three tombs contained bracelets and rings in gold and amethyst, silver sandals and intricately decorated and inscribed khopesh arms made from bronze and gold. The khopesh of tomb II bears the name of its owner, King Ip-Shemu-Abi and his father Abishemu. Other grave goods include a silver knife decorated with niello and gold, several bronze tridents, finely decorated teapot-shaped silver vases and various other vessels made of gold, silver, bronze, alabaster and terracotta.[92][93]

Tomb I contained a rare find of particular interest consisting of a fragment of a silver vase with spiral decorative patterns which French art history expert Edmond Pottier likened to those of the gold oenochoe from Tomb IV of Mycenae.[94] This silver vase demonstrates either Aegean artistic influence on local Gebalite art or could be proof of trade with Mycenae.[93][94]

Dating

French priest and archeologist Father Louis-Hugues Vincent, Pierre Montet, and other early scholars believed the tombs belonged to the Kings of Byblos of the Middle and Late Bronze Age, based on the characteristics of the painted pottery shards.[95]

Tomb I, II, and III

According to Virolleaud and Montet, the lavish Tombs I, II and III date back to the Middle Bronze Age, specifically the Twelfth Dynasty of Middle Kingdom Egypt (19th century BC). Montet based his dating on grave goods and royal Egyptian gifts found in the three tombs. Tomb I housed an ointment jar etched with the cartouche of Amenemhat III, and Tomb II contained an obsidian box bearing the name of his son and successor Amenemhat IV.[96][97]

Tomb V to IX

Montet matched the style of the pottery shards that he uncovered in the shaft of Tomb V to the vases found by English Egyptologist Flinders Petrie in the ruins of the palace of Akhenaten at Amarna. Both featured large brown or black painted bands, which divide the body of the receptacles into several parts, each of which contained vertical lines and circular motifs. Furthermore, the small vase handles are of identical shape. These similarities lead Montet to conclude that the Gebalite pottery shards were contemporary with the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1550 BC –c. 1077 BC).[98][99]

The other graves of the second group (tombs VI to IX) were all robbed in antiquity, making precise dating problematic. Some signs point to a range spanning from the end of the Middle Bronze Age to the Late Bronze Age.[100][99]

Attribution

Scholars, following the French art history expert Edmond Pottier, have noted the similarity of the spiral decorative patterns found in Tomb I to those of the gold oenochoe found in Tomb IV in Mycenae.[Compare] The names of some of the sarcophagi occupants are known from archeological finds. Tombs I belonged to King Abishemu (also romanized as "Abishemou" and "Abichemou") who received gifts from Pharaoh Amenemhat III, and Tomb II belonged to his son Ip-Shemu-Abi (also romanized as "Ypchemouabi") who received similar gifts from the son of Amenemhat IV. These gifts suggest that the reigns of Abishemu and Ip-Shemu-Abi were contemporaneous with those of late Twelfth Dynasty rulers.[34][102][103] The names of both Gebalite kings were inscribed on the khopesh staff found in Tomb II.[104] A passageway linked the chamber of Tomb I to the shaft of Tomb II. Montet posited that Ip-Shemu-Abi had this tunnel dug to remain in constant communication with his father.[105]

Montet proposed that Tomb IV was made for a vassal king of Egyptian origin, whom he believes was appointed by Egypt, thus interrupting the Gebalite dynastic suite. This theory was put forward based on Montet's discovery of an Egyptian scarab inscribed with the Egyptian name Medjed-Tebit-Atef.[102][106]

The sarcophagus of Tomb V belongs to Ahiram;[71] it stands apart from the other sarcophagi for its rich decoration and reliefs. Ahiram's sarcophagus was found in the chamber of Tomb V with two other plain sarcophagi. The lid of the sarcophagus features the effigies of the deceased, and that of his successor. The sarcophagus' funerary inscription identifies the names of the deceased king, and his son and successor Pilsibaal.[lower-alpha 9][81][109]

Earthenware fragments discovered in Tomb IX bore the name of Abishemu in Egyptian hieroglyphs.[41] This led scholars to attribute the sarcophagus to Abishemu, the second of that name, who could be the grandson of the elder. This assumption is based on the Phoenician custom of naming a prince after his grandfather.[110]

Function

Montet likened the Byblos tombs to mastabas and explained that in ancient Egyptian funerary texts, the soul of the deceased was believed to fly from the burial chamber, through the funerary shaft, to the ground-level chapel where priests would officiate.[111] He likened the tunnel connecting Tombs I and II to the tomb of Aba the son of Zau, a high official contemporaneous of Pharaoh Pepi II, who was buried in Deir el-Gabrawi in the same tomb as his father. Aba left an inscription detailing how he chose to share the tomb of his father to "be with him in the same place".[lower-alpha 10][111]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The demonyms Gebalite or Giblite are used in ancient sources to designate the general population of Gebal, the Phoenician name, and the origin of the modern name of the city (Jbeil).[15][16] In the context of this article, the demonym Gebalite was used since the site in question dates back to Phoenician times, and predates the Greek exonym "Byblos".

- ↑ "Now Byblus, the royal residence of Cinyras, is sacred to Adonis; but Pompey freed it from tyranny by beheading its tyrant with an axe; and it is situated on a height only a slight distance from the sea."[22]

- ↑ "R. IERAC BYBLOY. Femme tourrelée et voilée, assise dans un temple tétrastyle; au-dessous d'elle, un fleuve vu à mis-corps..." [Reverse IERAC BYBLOY. Turreted and veiled woman sitting in a tetrastyle temple; below her, a river seen from the side...][24]

- ↑ The rock bank found in this part of the peninsula, 4 m (13 ft) or 5 m (16 ft) from the current ground, is only 6 meters thick. The workers who dug the shaft, therefore, crossed it from the side and, not considering the depth sufficient, continued to dig in the clay.[44]

- ↑ "II semble bien que personne n'ait tenté de soulever le couvercle du sarcophage. Cependant quelqu'un est entré dans la grotte, à l'époque romaine sans doute, puis qu'on a trouvé mêlés aux pierres du mur de soutènement des fragments de verre qui datent sûrement de ce temps-là." [It seems that no one has tried to lift the lid of the sarcophagus. However, someone entered the cave, probably in Roman times, and glass fragments were found mixed with the stones of the retaining wall, which surely date from that time.][32]

- ↑ 2.32 m (7.6 ft) including the lid[32]

- ↑ Objects recovered from the royal tombs are numbered from 610 to 872 in Montet's Atlas.[86]

- ↑ "Vive le dieu bon, maître des Deux Terres, roi de la Haute et Basse Égypte, Ma'a-kherou-rê, aimé de Tourn, seigneur d'Héliopolis (On), à qui est donnée la vie éternelle comme Râ." ["Long Live The Good God, Master of both lands, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Ma'a-kherou-re, beloved of Tourn, Lord of Heliopolis (On), to whom eternal life is given as Ra."][90]

- ↑ The reconstruction of the name of Ahiram's son from the sarcophagus inscription was a point of contention due to the presence of a lacuna at the beginning of the prince's name. Since the Ahiram sarcophagus inscription was originally published in 1924, the name Ittobaal had prevailed. New epigraphic analyses reveal that this long-held interpretation is impossible, and a new reconstruction was presented using modern paleographic and calligraphic methods. These have demonstrated that Ahiram's son's name must have been Pulsibaal or Pilsibaal.[107][108]

- ↑ "I therefore made sure to be buried in the same tomb, with this Zau, in order to be with him in the same place, not that I did not have the means to make a second tomb, but I did this in order to see this Zau every day, in order to be with him in the same place."[111]

References

Citations

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2009.

- ↑ Cooper 2020, p. 298.

- ↑ Wilkinson 2011, p. 66.

- ↑ Moran 1992, p. 143.

- ↑ Head et al. 1911, p. 763.

- ↑ Huss 1985, p. 561.

- ↑ Lehmann 2008, pp. 120, 121, 154, 163–164.

- ↑ Salameh 2017, p. 353.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Harper 2000.

- ↑ DeVries 2006, p. 135.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 DeVries 1990, p. 124.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Awada Jalu 1995, p. 37.

- ↑ Redford 2021, pp. 89, 296.

- ↑ Jidejian 1986, p. 1.

- ↑ Head et al. 1911, p. 791.

- ↑ Barry 2016, headword: Gebal.

- ↑ Fischer 2003, p. 90.

- ↑ Segert 1997, p. 58.

- ↑ Moran 1992, p. 197.

- ↑ Charaf 2014, p. 442.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Renan 1864, p. 173.

- ↑ Strabo 1930, p. 263, §16.2.18.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Montet 1928, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Mionnet 1806, pp. 355–356.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Renan 1864, pp. 173–175.

- ↑ Dussaud 1956, p. 9.

- ↑ D. 1921, pp. 333–334.

- ↑ Montet 1921, pp. 158–168.

- ↑ Vincent 1925, p. 163.

- ↑ Virolleaud 1922, p. 1.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Dussaud 1956, p. 10.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 Virolleaud 1922, p. 275.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Montet 1928, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Montet 1928, pp. 145–147.

- ↑ Vincent 1925, p. 178.

- ↑ Sparks 2017, p. 249.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Lendering 2020.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 22–23, 143.

- ↑ Nigro 2020, p. 67.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 Porada 1973, p. 356.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Montet 1928, p. 212.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 214.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 155.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Montet 1928, p. 143.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Montet 1928, p. 144.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 145–146.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 146.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 148–150.

- ↑ Montet 1929, p. Pl. LXXVI (illustration).

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 150.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Montet 1928, p. 151.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Montet 1928, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Vincent 1925, PLANCHE VIII.

- ↑ Porada 1973, pp. 356–357.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Montet 1928, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ Dussaud 1924, p. 143.

- ↑ Vincent 1925, p. 189.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Montet 1928, p. 217.

- ↑ Porada 1973, p. 357.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 217, 225.

- ↑ Dunand 1937, XXVIII.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Montet 1928, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Montet 1928, p. 205.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 207–210.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 210.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 210–213.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Montet 1929, pp. 118–120.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Montet 1928, pp. 144, 146, 151–153 ,205–220, 229.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Porada 1973, p. 355.

- ↑ Virolleaud 1922, p. 276.

- ↑ Virolleaud 1922, pp. 275–276.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 154.

- ↑ Dunand 1939, p. 2.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Cook 1994, p. 1.

- ↑ Maïla Afeiche 2019.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 Montet 1928, p. 229.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Montet 1928, p. 230.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 231.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Porada 1973, p. 359.

- ↑ Lehmann 2008, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Montet 1928, p. 236.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 237.

- ↑ Teixidor 1987, p. 137.

- ↑ Montet 1929, pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 202.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 156–159.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Montet 1928, p. 159.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 157–159.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 155–204.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Dussaud 1930, pp. 176–178.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Pottier 1922, pp. 298–299.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 129, 219.

- ↑ Virolleaud 1922, pp. 273–290.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 16–17, 25, 219.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 220.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Kilani 2019, p. 97.

- ↑ Montet 1928, pp. 213–214.

- ↑ Montet 1929, PLANCHE CXI.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Dussaud 1930, p. 176.

- ↑ Montet 1927, p. 86.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 174.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 147.

- ↑ Montet 1928, p. 203.

- ↑ Lehmann 2005, p. 38.

- ↑ Lehmann 2015, p. 178.

- ↑ Lehmann 2008, p. 164.

- ↑ Helck 1971, p. 67.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 Montet 1928, pp. 147–148.

Bibliography

- Awada Jalu, Sawsan (1995). "The stones of Byblos". UNESCO Courier (Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization): 34–37. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000099738/PDF/099738engo.pdf.multi. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- Barry, John D. (2016) (in en). The Lexham Bible Dictionary. Bellingham, Washington: Lexham Press.

- Charaf, Hanan (2014). "The northern Levant (Lebanon) during the Middle Bronze Age". in Steiner, Margreet L. (in en). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000–332 BCE. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191662553. OCLC 1164893708. https://books.google.com/books?id=d_Z0AgAAQBAJ.

- Cook, Edward M. (1994). "On the Linguistic Dating of the Phoenician Ahiram Inscription (KAI 1)". Journal of Near Eastern Studies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 53 (1): 33–36. doi:10.1086/373654. ISSN 0022-2968. https://www.jstor.org/stable/545356.

- Cooper, Julien (2020) (in en). Toponymy on the Periphery: Placenames of the Eastern Desert, Red Sea, and South Sinai in Egyptian Documents from the Early Dynastic until the End of the New Kingdom. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 9789004422216. OCLC 1240671488. https://books.google.com/books?id=znD-DwAAQBAJ.

- D., R. (1921). "Mission Pierre Montet à Byblos" (in fr). Syria (Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient) 2 (4): 333–334. ISSN 0039-7946. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4389726.

- DeVries, LaMoine F. (1990). Mills, Watson E.. ed (in en). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737. OCLC 613917443. https://books.google.com/books?id=goq0VWw9rGIC.

- DeVries, LaMoine F. (2006) (in en). Cities of the Biblical World: An Introduction to the Archaeology, Geography, and History of Biblical Sites. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781556351204. OCLC 1026419222. https://books.google.com/books?id=aOJJAwAAQBAJ.

- Dunand, Maurice (1937) (in French). Fouilles de Byblos, Tome 1er, 1926–1932 (Atlas). Bibliothèque archéologique et historique. 24. Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner. OCLC 85977250. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9107356n/f1.item.

- Dunand, Maurice (1939) (in fr). Fouilles de Byblos: Tome 1er, 1926–1932. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique. 24. Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner. OCLC 35255029. https://books.google.com/books?id=cYIeAAAAMAAJ.

- Dussaud, René (1924). "Les inscriptions phéniciennes du tombeau d'Ahiram, roi de Byblos" (in fr). Syria (Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient) 5 (2): 135–157. doi:10.3406/syria.1924.3038. OCLC 977806804. https://www.persee.fr/doc/syria_0039-7946_1924_num_5_2_3038.

- Dussaud, René (1930). "Les quatre campagnes de fouilles de M. Pierre Montet a Byblos" (in fr). Syria (Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient) 11 (2): 164–187. doi:10.3406/syria.1930.3470. ISSN 0039-7946. OCLC 754446601. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4237002.

- Dussaud, René (1956). "L'oeuvre scientifique syrienne de M.Charles Virolleaud" (in fr). Syria (Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient) 33 (1): 8–12. doi:10.3406/syria.1956.5186. OCLC 754457329. https://www.persee.fr/doc/syria_0039-7946_1956_num_33_1_5186.

- Fischer, Steven Roger (2003) (in en). History of Writing. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781861891679. OCLC 439272651. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ywo0M9OpbXoC.

- Harper, Douglas (2000). "Etymology of Byblos". Online Etymology Dictionary. Tupalo, Mississippi: Douglas Harper. https://www.etymonline.com/word/byblos. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- Head, Barclay Vincent; Hill, Sir George Francis; MacDonald, George; Wroth, Warwick William (1911) (in en). Historia Numorum: A Manual of Greek Numismatics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780722221877. OCLC 1083895850. https://books.google.com/books?id=QDFOAAAAYAAJ.

- Helck, Wolfgang (1971) (in de). Die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien im 3. und 2. Jahrtausend v.Chr.: 2., verbesserte Auflage. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 9783447012980. OCLC 1049030285. https://books.google.com/books?id=dtMiEAAAQBAJ.

- Huss, Werner (1985) (in de). Geschichte der Karthager. Munich: C.H. Beck. p. 561. ISBN 9783406306549. OCLC 887765515. https://books.google.com/books?id=NvEK7kc3qnQC.

- Jidejian, Nina (1986). Byblos through the ages. Beirut: Dar el-Machreq Publishers. OCLC 913477845. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ua_dzQEACAAJ.

- Kilani, Marwan (2019) (in en). Byblos in the Late Bronze Age: Interactions between the Levantine and Egyptian Worlds. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 9789004416604. OCLC 8303726422. https://books.google.com/books?id=IgT1DwAAQBAJ.

- Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2005) (in de). Die Inschrift(en) des Ahirom-Sarkophags und die Schachtinschrift des Grabes V in Jbeil (Byblos). Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern. ISBN 9783805335089. OCLC 76773474. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/76773474.

- Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2008). "Calligraphy and Craftsmanship in the Ahirom inscription. Considerations on skilled linear flat writing in early first millennium Byblos". MAARAV (Santa Monica, California: Western Academic Press) 15 (2): 119–164. doi:10.1086/MAR200815202. https://www.academia.edu/4306363.

- Lehmann, Reinhard G. (February 2015). "Wer war Aḥīrōms Sohn (KAI 1:1)? Eine kalligraphisch-prosopographische Annäherung an eine epigraphisch offene Frage". Fünftes Treffen der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Semitistik in der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, University of Basel. 425. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. pp. 163–180. OCLC 918796397. https://www.academia.edu/10086901.

- Lendering, Jona (2020). "Byblos". https://www.livius.org/articles/place/byblos/.

- Maïla Afeiche, Anne-Marie (24 September 2019). "Le sarcophage d'Ahiram roi de Byblos". Beirut. https://www.agendaculturel.com/article/le-sarcophage-dahiram-roi-de-byblos.

- Mionnet, Théodore Edme (1806) (in fr). Description de médailles antiques, grecques et romaines ; avec leur degré de rareté et leur estimation ; ouvrage servant de catalogue à une suite de plus de vingt mille empreintes en soufre, prise sur les pièces originales. Paris: Imprimerie de Testu. OCLC 632656145. http://archive.org/details/bub_gb_tN4Q3F1EEiIC.

- Montet, Pierre (1921). "Lettre à M. Clermont-Ganneau" (in fr). Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et des Belles Lettres) 65 (2): 158–168. doi:10.3406/crai.1921.74450. 4649740372. ISSN 0065-0536. https://www.persee.fr/doc/crai_0065-0536_1921_num_65_2_74450.

- Montet, Pierre (1927). "Un Egyptien, roi de Byblos, sous la XIIe dynastíe Étude sur deux scarabées de la collection de Clercq" (in Fr). Syria (Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient) 8 (2): 85–92. doi:10.3406/syria.1927.3277. ISSN 0039-7946. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4195343.

- Montet, Pierre (1928) (in fr). Byblos et l'Egypte: Quatre Campagnes de Fouilles à Gebeil 1921–1922–1923–1924 (Texte). Bibliothèque archéologique et historique. 11. Paris: Geuthner. OCLC 1071294753. http://archive.org/details/Montet1928.

- Montet, Pierre (1929) (in fr). Byblos et l'Egypte Quatre Campagnes de Fouilles à Gebeil 1921–1922–1923–1924 (Atlas). Bibliothèque archéologique et historique. 11. Paris: Geuthner. OCLC 904661212. http://archive.org/details/BAH11MontetPierreByblosEtLEgypteQuatreCampagnesDeFouillesGebeil1921192219231924Atlas1929LR.

- Moran, William L. (1992) (in en). The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801842511. OCLC 797943180. https://books.google.com/books?id=GbpiAAAAMAAJ.

- Nigro, Lorenzo (2020). "Byblos, an ancient capital of the Levant". La Revue Phénicienne (Beirut) (Spécial 100 ans): 61–74. https://www.academia.edu/49635763.

- Porada, Edith (1973). "Notes on the Sarcophagus of Ahiram" (in en). Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary) 5 (1): 355–372. OCLC 602273437. https://janes.scholasticahq.com/article/2166-notes-on-the-sarcophagus-of-ahiram.

- Pottier, Edmond (1922). "Observations sur quelques objets trouvés dans le sarcophage de Byblos. Lettre à M. René Dussaud, Directeur de la revue Syria" (in fr). Syria (Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient) 3 (4): 298–306. doi:10.3406/syria.1922.8854. ISSN 0039-7946. https://www.persee.fr/doc/syria_0039-7946_1922_num_3_4_8854.

- Redford, Donald B. (2021) (in en). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691214658. OCLC 1241099443. https://books.google.com/books?id=G9PgDwAAQBAJ.

- Renan, Ernest (1864) (in fr). Mission de Phénicie Dirigée par M. Ernest Renan. Paris: Imprimerie impériale. OCLC 763570479. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5529563s.

- Salameh, Franck (2017) (in en). The other Middle East: An anthology of modern Levantine literature. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300204445. OCLC 1065338550. https://books.google.com/books?id=jzFDDwAAQBAJ.

- Segert, Stanislav (1997). Kaye, Alan S.. ed (in en). Phonologies of Asia and Africa - including the Caucasus. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060194. OCLC 929631154. https://books.google.com/books?id=T6jmziooEk0C.

- Sparks, Rachael Thyrza (5 July 2017) (in en). Stone Vessels in the Levant. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 9781351547789. OCLC 994205911. https://books.google.com/books?id=Yj8rDwAAQBAJ.

- Strabo (1930). Geography, Volume VII: Books 15–16. Translated by Horace Leonard Jones. Loeb Classical Library 241. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 263. OCLC 899735754. https://archive.org/details/L241StraboGeographyVII1516/page/262/mode/2up. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- Teixidor, Javier (1987). "L' inscription d'Ahiram à nouveau" (in fr). Syria (Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient) 64 (1): 137–140. doi:10.3406/syria.1987.6979. OCLC 754460302. https://www.persee.fr/doc/syria_0039-7946_1987_num_64_1_6979.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2009). "Byblos" (in en). Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Center. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/295/.

- Vincent, Louis-Hugues (1925). "Les fouilles de Byblos" (in fr). Revue Biblique (Louvain: Peeters Publishers) 34 (2): 161–193. ISSN 1240-3032. OCLC 718118625. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44102762.

- Virolleaud, Charles (1922). "Découverte à Byblos d'un hypogée de la douzième dynastie égyptienne" (in Fr). Syria (Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient) 3 (4): 273–290. doi:10.3406/syria.1922.8851. ISSN 0039-7946. OCLC 1136131170. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4195157.

- Wilkinson, Toby (2011). The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. New York: A&C Black. ISBN 9780679604297. OCLC 710823381. https://books.google.com/books?id=L-mWx_EM9tEC.

|