Religion:Hypostasis (philosophy and religion)

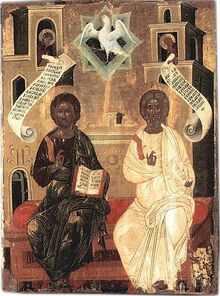

Hypostasis (plural: hypostases), from the Greek ὑπόστασις (hypóstasis), is the underlying state or underlying substance and is the fundamental reality that supports all else. In Neoplatonism the hypostasis of the soul, the intellect (nous) and "the one" was addressed by Plotinus.[1] In Christian theology, the Holy Trinity consists of three hypostases: Hypostasis of the Father, Hypostasis of the Son, and Hypostasis of the Holy Spirit.[2]

Ancient Greek philosophy

Pseudo-Aristotle used hypostasis in the sense of material substance.[3]

Neoplatonists argue that beneath the surface phenomena that present themselves to our senses are three higher spiritual principles, or hypostases, each one more sublime than the preceding. For Plotinus, these are the Soul, the Intellect, and the One.[1][4]

Christian theology

The term hypostasis has a particular significance in Christian theology, particularly in Christian triadology (study of the Holy Trinity), and also in Christology (study of Christ).[5][6]

In Christian triadology

In Christian triadology three specific theological concepts have emerged throughout history,[7] in reference to number and mutual relations of divine hypostases:

- the Monohypostatic (or miahypostatic) concept advocates that God has only one hypostasis;[8][9]

- the Dyohypostatic concept advocates that God has two hypostases (Father and Son);[10]

- the Trihypostatic concept advocates that God has three hypostases (Father, Son and the Holy Spirit).[11]

Origen "taught that there were three hypostases within the Godhead."[12]:185 "Arius ... spoke readily of the hypostases of Father, Son and Holy Spirit."[12]:187 Asterius, a leading Arian, "said that there were three hypostases".[12]:187

Eustathius and Marcellus promoted a monohypostatic interpretation of the Nicene Creed;[13]:235 They were Sabellians: "It seems most likely that Eustathius was primarily deposed for the heresy of Sabellianism."[13]:211 Marcellus of Ancyra "cannot be acquitted of Sabellianism".[14]

The "clear inference from [Athanasius'] usage" is that "there is only one hypostasis in God."[15]:48 The Western Church also preferred a one hypostasis theology: "[Athanasius] had attended the Council of Serdica among the Western bishops in 343, and a formal letter of that Council had emphatically opted for the belief in one, and only one, hypostasis as orthodoxy. Athanasius certainly accepted this doctrine at least up to 359, even though he tried later to suppress this fact."[12]:444

Both traditional Trinity doctrine and the Arians taught three distinct hypostases in the Godhead. The difference is that, in the Trinity doctrine, they are one ousia ('substance').

Hypostasis and ousia

Nicene Creed

"One of the most striking aspects of Nicaea in comparison to surviving baptismal creeds from the period, and even in comparison to the creed which survives from the council of Antioch in early 325, is its use of the technical terminology of ousia and hypostasis."[15]:92

"Considerable confusion existed about the use of the terms hypostasis and ousia at the period when the Arian Controversy broke out."[12]:181 "The ambiguous anathema in N (the Nicene Creed) against those who believe that the Son is 'from another hypostasis or ousia than the Father' ... (is one example) of this unfortunate semantic misunderstanding."[12]:181 R. P. C. Hanson says that the Nicene Creed "apparently (but not quite certainly) identifies hypostasis and ousia."[12]:188

Trinitarian doctrine

Hanson described Trinitarian doctrine, as developed through the fourth-century Arian controversy, as follows:

"The champions of the Nicene faith ... developed a doctrine of God as a Trinity, as one substance or ousia who existed as three hypostases, three distinct realities or entities (I refrain from using the misleading word 'Person'), three ways of being or modes of existing as God." Hanson Lecture

Hanson explains hypostases as 'realities', 'entities', 'ways of being', and 'modes of existing' but says that the term person is misleading. Person, as used in English, where each person is a distinct entity with his or her own mind and will, is not equivalent to the concept of hypostasis in the "doctrine of God as a Trinity."

But the main point of the definition is that God is one "ousia who existed as three hypostases." The purpose here is to show that the Nicene Creed probably uses these terms as synonyms but that their meanings were changed to enable the formulation of the central doctrine of the Trinity.

Greek philosophy

These terms originate from Greek philosophy, where they had essentially the same meaning and meant the fundamental reality that supports all else. In a Christian context, this concept may refer to God or the Ultimate Reality.

The Bible

According to Hanson, "the only strictly theological use (of the word hypostasis) is that of Hebrews 1:3, where the Son is described as 'the impression of the nature' [hypostasis] of God."[12]:182 "The word also occurs twenty times in the LXX (the ancient Greek translation of the Old Testament), but only one of them can be regarded as theologically significant. ... At Wisdom 16:21 the writer speaks of God's hypostasis, meaning his nature; and no doubt this is why Hebrews uses the term 'impression of his nature'."[12]:182

The Bible never refers to God's ousia.

Early Church Fathers

In early Christian writings, hypostasis was used to denote 'being' or 'substantive reality' and was not always distinguished in meaning from terms like ousia ('essence'), substantia ('substance') or qnoma (specific term in Syriac Christianity).[16] It was used in this way by Tatian and Origen.[7]

"Tertullian at the turn of the second to the third centuries had already used the Latin word substantia (substance) of God ... God therefore had a body and indeed was located at the outer boundaries of space. ... It was possible for Tertullian to think of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit sharing this substance, so that the relationship of the Three is, in a highly refined sense, corporeal. ... He can use the expression Unius substantiae ('of one substance'). This has led some scholars to see Tertullian as an exponent of Nicene orthodoxy before Nicaea ... But this is a far from plausible theory. Tertullian's materialism is ... a totally different thing from any ideas of ousia or homoousios canvassed during the fourth century."[12]:184

During Arian controversy

When the Arian controversy began, hypostasis and ousia were synonyms:

"For many people at the beginning of the fourth century the word hypostasis and the word ousia had pretty well the same meaning."[12]:181 "For at least the first half of the period 318–381, and in some cases considerably later, ousia and hypostasis are used as virtual synonyms."[12]:183

Therefore, when dealing with documents from or before the beginning of the Arian controversy:

[The two terms] did not mean, and should not be translated, 'person' and 'substance', as they were used when at last the confusion was cleared up and these two distinct meanings were permanently attached to these words.[12]:181

Even for Athanasius, some decades after the controversy began, "hypostasis and ousia were still synonymous."[12]:440

Alternative views

Among those who regarded them as synonyms, two groups may be identified:

Three hypostases

One group said that the Father, Son, and Spirit are three hypostases (three distinct realities), each with his own ousia:

Among the pre-Nicene church fathers, Origen "used hypostasis and ousia freely as interchangeable terms to describe the Son's distinct reality within the Godhead. ... He taught that there were three hypostases within the Godhead.".[12]:185 As examples from the fourth century, Hanson includes Eusebius of Caesarea and Eusebius of Nicomedia, two of the main anti-Nicenes.

One hypostasis

The other group said that the Father, Son, and Spirit are one single hypostasis and one ousia, meaning that they are one single reality or being:

Among the pre-Nicene church fathers, "Dionysius of Rome ... said that it is wrong to divide the divine monarchy 'into three ... separated hypostases ... people who hold this in effect produce three gods'."[12]:185 In the fourth century, the Sabellians Eustathian and Marcellus] were famous for this teaching.[17] It is argued that Athanasius also fell into this category.[18] The "clear inference from [Athanasius'] usage" is that "there is only one hypostasis in God." (LA, 48)

Distinction by Arians

It is often said that the first person to propose a difference in the meanings of hypostasis and ousia, and for using hypostasis as synonym of person, was Basil of Caesarea,[19] namely in his letters 214 (375 A.D.)[20] and 236 (376 A.D.)[21] However Hanson, in his discussion of the two terms, stated that some Arians had already made this distinction decades before Basil:

With respect to Arius, Hanson wrote: "It seems likely that he was one of the few during this period who did not confuse the two." "Arius ... spoke readily of the hypostases of Father, Son and Holy Spirit" but "no doubt he believed that the Father and the Son were of unlike substance."[12]:187 Speaking of another prominent Arian, Hanson says: "Asterius certainly taught that the Father and the Son were distinct and different in their hypostases. ... But he also described the Son as 'the exact image of the ousia and counsel and glory and power' of the Father. Once again we find a writer who clearly did not confuse ousia and hypostasis."[12]:187

Asterius is called an Arian but, as indicated by the quote above, "he thought that the resemblance of the Son to the Father was closer than Arius conceived."[12]:187

Cappadocian Fathers

The three Cappadocian Fathers are Basil of Caesarea (330 to 379), Gregory of Nazianzus (329 to 389), and Gregory of Nyssa (335 to about 395) who was one of Basil's younger brothers.[12]:676

"Basil's most distinguished contribution towards the resolving of the dispute about the Christian doctrine of God was in his clarification of the vocabulary."[12]:690

"Basil uses hypostasis to mean 'Person of the Trinity' as distinguished from 'substance' which is usually expressed as either ousia or 'nature' (physis) or 'substratum'."[12]:690–691

Not one undivided substance

However, the Cappadocians did not yet understand God as one undivided ousia (substance), as in the Trinity doctrine. They said that the Father, Son, and Spirit have exactly the same type of substance, but each has his own substance. This can be shown as follows:

Unalterably like in respect of ousia

Basil began his career as theologian as a Homoiousian. He therefore believed similar to other Homoiousians, that the Son's substance is similar to the Father's:

"[Basil] came from what might be called an 'Homoiousian' background." (RH, 699) Therefore, "the doctrine of 'like in respect of ousia' was one which they could accept, or at least take as a starting point, and which caused them no uneasiness."[12]:678

This means that Basil believed in two distinct hypostases with similar substances. Later, he replaced the concept of 'similar substance' with 'exactly the same substance' but retained the idea of two distinct hypostases:

He says that in his own view 'like in respect of ousia' (the slogan of the party of Basil of Ancyra) was an acceptable formula, provided that the word 'unalterably' was added to it, for then it would be equivalent to homoousios." "Basil himself prefers homoousios." "Basil has moved away from but has not completely repudiated his origins.[12]:694

This also meant that Basil understood homoousios in a generic sense of two beings with the same type of substance, rather than two beings sharing one single substance.

The general and the particular

Basil of Caesarea explains that the distinction between ousia and hypostases is the same as that between the general and the particular; as, for instance, between the animal and the particular man:

He wrote: "That relation which the general has to the particular, such a relation has the ousia to the hypostasis."[12]:692

"In the DSS [Basil] discusses the idea that the distinction between the Godhead and the Persons is that between an abstract essence, such as humanity, and its concrete manifestations, such as man."[12]:698

"Elsewhere he can compare the relation of ousia to hypostasis to that of 'living being' to a particular man and apply this distinction directly to the three Persons of the Trinity." This suggests "that the three are each particular examples of a 'generic' Godhead."[12]:692

Basil "argued that [homoousios] was preferable because it actually excluded identity of hypostases. This, with the instances which we have already seen in which Basil compared the relation of hypostasis to ousia in the Godhead to that of particular to general, or of a man to 'living beings', forms the strongest argument for Harnack's hypothesis."[12]:697 "Harnack ... argued that Basil and all the Cappadocians interpreted homoousios only in a 'generic' sense ... that unity of substance was turned into equality of substance."[12]:696

Later developments

Consensus was not achieved without some confusion at first in the minds of Western theologians since in the West the vocabulary was different.[22] Many Latin-speaking theologians understood hypo-stasis as 'sub-stantia' (substance); thus when speaking of three hypostases in the Godhead, they may have suspected three substances or tritheism. However, after the mid-fifth-century Council of Chalcedon, the word came to be contrasted with ousia and was used to mean 'individual reality', especially in the trinitarian and Christological contexts. The Christian concept of the Trinity is often described as being one God existing in three distinct hypostases/personae/persons.[23]

In Christology

Within Christology, two specific theological concepts have emerged throughout history, in reference to the Hypostasis of Christ:

- monohypostatic concept (in Christology) advocates that Christ has only one hypostasis;[24]

- dyohypostatic concept (in Christology) advocates that Christ has two hypostases (divine and human).[25]

John Calvin's views

John Calvin wrote: "The word ὑπόστασις which, by following others, I have rendered substance, denotes not, as I think, the being or essence of the Father, but his person; for it would be strange to say that the essence of God is impressed on Christ, as the essence of both is simply the same. But it may truly and fitly be said that whatever peculiarly belongs to the Father is exhibited in Christ, so that he who knows him knows what is in the Father. And in this sense do the orthodox fathers take this term, hypostasis, considering it to be threefold in God, while the essence (οὐσία) is simply one. Hilary everywhere takes the Latin word substance for person. But though it be not the Apostle's object in this place to speak of what Christ is in himself, but of what he is really to us, yet he sufficiently confutes the Asians and Sabellians; for he claims for Christ what belongs to God alone, and also refers to two distinct persons, as to the Father and the Son. For we hence learn that the Son is one God with the Father, and that he is yet in a sense distinct from him, so that a subsistence or person belongs to both."[26]

See also

- Aspect

- Haecceity – a term used by the followers of Duns Scotus to refer to that which formally distinguishes one thing from another with a common nature

- Hypokeimenon

- Hypostatic union

- Hypostatic abstraction

- Instantiation principle

- Kalyptos in Gnosticism

- Noema – a similar term used by Edmund Husserl

- Prakṛti – a similar term found in Hinduism

- Principle of individuation

- Prosopon or persona

- Reification (fallacy)

- Substance theory

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Anton 1977, pp. 258–271.

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Christianity. 5. Fahlbusch, Erwin, Lochman, Jan Milič, Mbiti, John S., Pelikan, Jaroslav, 1923–2006, Vischer, Lukas, Bromiley, G. W. (Geoffrey William). Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdman. 2008. p. 543. ISBN 978-0802824134. OCLC 39914033. https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofch0001unse_t6f2/page/543.

- ↑ Pseudo-Aristotle, De mundo, 4.19.

- ↑ Neoplatonism (Ancient Philosophies) by Pauliina Remes (2008), University of California Press ISBN:0520258347, pp. 48–52.

- ↑ Meyendorff 1989, pp. 190–192, 198, 257, 362.

- ↑ Daley 2009, pp. 342–345.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ramelli 2012, pp. 302–350.

- ↑ Lienhard 1993, pp. 97–99.

- ↑ Bulgakov 2009, pp. 82, 143–144.

- ↑ Lienhard 1993, pp. 94–97.

- ↑ Bulgakov 2009, pp. 15, 143, 147.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 12.22 12.23 12.24 12.25 12.26 12.27 12.28 Hanson, Richard P. C (1987). The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God – The Arian Controversy 318–381.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hanson, Richard P. C (1988). The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God – The Arian Controversy 318–381. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. p. 235. https://archive.org/details/searchforchristi0000hans/page/235/mode/1up. Retrieved 2023-12-01. "If we are to take the Nicene Creed at its face value, the theology of Eustathius and Marcellus was the theology which triumphed at Nicaea. That creed admits the possibility of only one ousia and one hypostasis. This was the hallmark of the theology of these two men."

- ↑ Hanson Lecture

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ayres, Lewis (2004). Nicaea and its legacy.

- ↑ Meyendorff 1989, p. 173.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Johannes (2018-03-31). "Ousía and hypostasis from the philosophers to the councils". http://ousiakaihypostasis.blogspot.com/.

- ↑ "St Basil the Great, Letters – Third Part – Full text, in English – 1". https://www.elpenor.org/basil/letters-3.asp.

- ↑ "St Basil the Great, Letters – Third Part – Full text, in English – 39". https://www.elpenor.org/basil/letters-3.asp?pg=39.

- ↑ Weedman 2007, pp. 95–97.

- ↑ González, Justo L (2005), "Hypostasis", Essential Theological Terms, Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, pp. 80–81, ISBN 978-0664228101, https://books.google.com/books?id=DU6RNDrfd-0C

- ↑ McGuckin 2011, p. 57.

- ↑ Kuhn 2019.

- ↑ John Calvin, Commentary on Hebrews, 35 (CCEL PDF ed.); https://ccel.org/ccel/c/calvin/calcom44/cache/calcom44.pdf; plain text version: https://www.studylight.org/commentaries/eng/cal/hebrews-1.html

Sources

- Anton, John P. (1977). "Some Logical Aspects of the Concept of Hypostasis in Plotinus". The Review of Metaphysics 31 (2): 258–271. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20127050.

- Bulgakov, Sergius (2009). The Burning Bush: On the Orthodox Veneration of the Mother of God. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0802845740. https://books.google.com/books?id=1ixfwIjq4n8C.

- Daley, Brian E. (2009). "The Persons in God and the Person of Christ in Patristic Theology: An Argument for Parallel Development". God in Early Christian Thought. Leiden & Boston: Brill. pp. 323–350. ISBN 978-9004174122. https://books.google.com/books?id=9bAyYn_QkbkC.

- Kuhn, Michael F. (2019). God is One: A Christian Defence of Divine Unity in the Muslim Golden Age. Carlisle: Langham Publishing. ISBN 978-1783685776. https://books.google.com/books?id=mXPnDwAAQBAJ.

- Lienhard, Joseph T. (1993). "The Arian Controversy: Some Categories Reconsidered". Doctrines of God and Christ in the Early Church. New York and London: Garland Publishing. pp. 87–109. ISBN 978-0815310693. https://books.google.com/books?id=1JQ-1IZL9DcC.

- Loon, Hans van (2009). The Dyophysite Christology of Cyril of Alexandria. Leiden & Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004173224. https://books.google.com/books?id=BVDsO6IbdOYC.

- McGuckin, John Anthony, ed (2011). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. 1. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405185394. https://books.google.com/books?id=N3y2wwEACAAJ.

- McLeod, Frederick G. (2010). "Theodore of Mopsuestia's Understanding of Two Hypostaseis and Two Prosopa Coinciding in One Common Prosopon". Journal of Early Christian Studies 18 (3): 393–424. doi:10.1353/earl.2010.0011. https://doi.org/10.1353/earl.2010.0011.

- Meyendorff, John (1983). Byzantine Theology: Historical Trends and Doctrinal Themes (2nd revised ed.). New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0823209675. https://books.google.com/books?id=GoVeDXMvY-8C.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D.. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0881410563. https://books.google.com/books?id=6J_YAAAAMAAJ.

- Owens, Joseph (1951). The Doctrine of Being in the Aristotelian Metaphysics: A Study in the Greek Background of Mediaeval Thought. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. https://books.google.com/books?id=xl-zAAAAMAAJ.

- Pásztori-Kupán, István (2006). Theodoret of Cyrus. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1134391769. https://books.google.com/books?id=9LVdGlohtkAC.

- Ramelli, Ilaria (2012). "Origen, Greek Philosophy, and the Birth of the Trinitarian Meaning of Hypostasis". The Harvard Theological Review 105 (3): 302–350. doi:10.1017/S0017816012000120. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23327679.

- Toepel, Alexander (2014). "Zur Bedeutung der Begriffe Hypostase und Prosopon bei Babai dem Großen". Georgian Christian Thought and Its Cultural Context. Leiden & Boston: Brill. pp. 151–171. ISBN 978-9004264274. https://books.google.com/books?id=XpMXAwAAQBAJ.

- Turcescu, Lucian (1997). "Prosopon and Hypostasis in Basil of Caesarea's "Against Eunomius" and the Epistles". Vigiliae Christianae 51 (4): 374–395. doi:10.2307/1583868. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1583868.

- Weedman, Mark (2007). The Trinitarian Theology of Hilary of Poitiers. Leiden & Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004162242. https://books.google.com/books?id=9Z8GhJl6BG8C.

|