Selection principle

In mathematics, a selection principle is a rule asserting the possibility of obtaining mathematically significant objects by selecting elements from given sequences of sets. The theory of selection principles studies these principles and their relations to other mathematical properties. Selection principles mainly describe covering properties, measure- and category-theoretic properties, and local properties in topological spaces, especially function spaces. Often, the characterization of a mathematical property using a selection principle is a nontrivial task leading to new insights on the characterized property.

The main selection principles

In 1924, Karl Menger [1] introduced the following basis property for metric spaces: Every basis of the topology contains a sequence of sets with vanishing diameters that covers the space. Soon thereafter, Witold Hurewicz[2] observed that Menger's basis property is equivalent to the following selective property: for every sequence of open covers of the space, one can select finitely many open sets from each cover in the sequence, such that the family of all selected sets covers the space. Topological spaces having this covering property are called Menger spaces.

Hurewicz's reformulation of Menger's property was the first important topological property described by a selection principle. Let and be classes of mathematical objects. In 1996, Marion Scheepers[3] introduced the following selection hypotheses, capturing a large number of classic mathematical properties:

- : For every sequence of elements from the class , there are elements such that .

- : For every sequence of elements from the class , there are finite subsets such that .

In the case where the classes and consist of covers of some ambient space, Scheepers also introduced the following selection principle.

- : For every sequence of elements from the class , none containing a finite subcover, there are finite subsets such that .

Later, Boaz Tsaban identified the prevalence of the following related principle:

- : Every member of the class includes a member of the class .

The notions thus defined are selection principles. An instantiation of a selection principle, by considering specific classes and , gives a selection (or: selective) property. However, these terminologies are used interchangeably in the literature.

Variations

For a set and a family of subsets of , the star of in is the set .

In 1999, Ljubisa D.R. Kocinac introduced the following star selection principles:[4]

- : For every sequence of elements from the class , there are elements such that .

- : For every sequence of elements from the class , there are finite subsets such that .

The star selection principles are special cases of the general selection principles. This can be seen by modifying the definition of the family accordingly.

Covering properties

Covering properties form the kernel of the theory of selection principles. Selection properties that are not covering properties are often studied by using implications to and from selective covering properties of related spaces.

Let be a topological space. An open cover of is a family of open sets whose union is the entire space For technical reasons, we also request that the entire space is not a member of the cover. The class of open covers of the space is denoted by . (Formally, , but usually the space is fixed in the background.) The above-mentioned property of Menger is, thus, . In 1942, Fritz Rothberger considered Borel's strong measure zero sets, and introduced a topological variation later called Rothberger space (also known as C space). In the notation of selections, Rothberger's property is the property .

An open cover of is point-cofinite if it has infinitely many elements, and every point belongs to all but finitely many sets . (This type of cover was considered by Gerlits and Nagy, in the third item of a certain list in their paper. The list was enumerated by Greek letters, and thus these covers are often called -covers.) The class of point-cofinite open covers of is denoted by . A topological space is a Hurewicz space if it satisfies .

An open cover of is an -cover if every finite subset of is contained in some member of . The class of -covers of is denoted by . A topological space is a γ-space if it satisfies .

By using star selection hypotheses one obtains properties such as star-Menger (), star-Rothberger () and star-Hurewicz ().

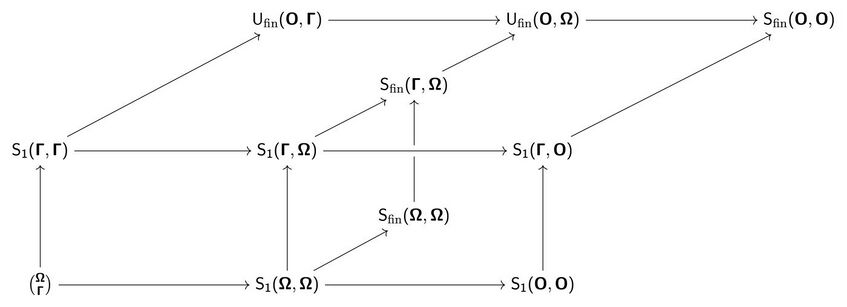

The Scheepers diagram

There are 36 selection properties of the form , for and . Some of them are trivial (hold for all spaces, or fail for all spaces). Restricting attention to Lindelöf spaces, the diagram below, known as the Scheepers diagram,[3][5] presents nontrivial selection properties of the above form, and every nontrivial selection property is equivalent to one in the diagram. Arrows denote implications.

|

Local properties

Selection principles also capture important local properties.

Let be a topological space, and . The class of sets in the space that have the point in their closure is denoted by . The class consists of the countable elements of the class . The class of sequences in that converge to is denoted by .

- A space is Fréchet–Urysohn if and only if it satisfies for all points .

- A space is strongly Fréchet–Urysohn if and only if it satisfies for all points .

- A space has countable tightness if and only if it satisfies for all points .

- A space has countable fan tightness if and only if it satisfies for all points .

- A space has countable strong fan tightness if and only if it satisfies for all points .

Topological games

There are close connections between selection principles and topological games.

The Menger game

Let be a topological space. The Menger game played on is a game for two players, Alice and Bob. It has an inning per each natural number . At the inning, Alice chooses an open cover of , and Bob chooses a finite subset of . If the family is a cover of the space , then Bob wins the game. Otherwise, Alice wins.

A strategy for a player is a function determining the move of the player, given the earlier moves of both players. A strategy for a player is a winning strategy if each play where this player sticks to this strategy is won by this player.

- A topological space is if and only if Alice has no winning strategy in the game played on this space.[2][3]

- Let be a metric space. Bob has a winning strategy in the game played on the space if and only if the space is -compact.[6][7]

Note that among Lindelöf spaces, metrizable is equivalent to regular and second-countable, and so the previous result may alternatively be obtained by considering limited information strategies.[8] A Markov strategy is one that only uses the most recent move of the opponent and the current round number.

- Let be a regular space. Bob has a winning Markov strategy in the game played on the space if and only if the space is -compact.

- Let be a second-countable space. Bob has a winning Markov strategy in the game played on the space if and only if he has a winning perfect-information strategy.

In a similar way, we define games for other selection principles from the given Scheepers Diagram. In all these cases a topological space has a property from the Scheepers Diagram if and only if Alice has no winning strategy in the corresponding game.[9] But this does not hold in general: Let be the family of k-covers of a space. That is, such that every compact set in the space is covered by some member of the cover. Francis Jordan demonstrated a space where the selection principle holds, but Alice has a winning strategy for the game [10]

Examples and properties

- Every space is a Lindelöf space.

- Every σ-compact space (a countable union of compact spaces) is .

- .

- .

- Assuming the Continuum Hypothesis, there are sets of real numbers witnessing that the above implications cannot be reversed.[5]

- Every Luzin set is but no .[11][12]

- Every Sierpiński set is Hurewicz.[13]

Subsets of the real line (with the induced subspace topology) holding selection principle properties, most notably Menger and Hurewicz spaces, can be characterized by their continuous images in the Baire space . For functions , write if for all but finitely many natural numbers . Let be a subset of . The set is bounded if there is a function such that for all functions . The set is dominating if for each function there is a function such that .

- A subset of the real line is if and only if every continuous image of that space into the Baire space is not dominating.[14]

- A subset of the real line is if and only if every continuous image of that space into the Baire space is bounded.[14]

Connections with other fields

General topology

Let P be a property of spaces. A space is productively P if, for each space with property P, the product space has property P.

- Every separable productively paracompact space is .

- Assuming the Continuum Hypothesis, every productively Lindelöf space is productively [16]

- Let be a subset of the real line, and be a meager subset of the real line. Then the set is meager.[17]

Measure theory

- Every subset of the real line is a strong measure zero set.[11]

Function spaces

Let be a Tychonoff space, and be the space of continuous functions with pointwise convergence topology.

- satisfies if and only if is Fréchet–Urysohn if and only if is strong Fréchet–Urysohn.[18]

- satisfies if and only if has countable strong fan tightness.[19]

- satisfies if and only if has countable fan tightness.[20][5]

See also

- Compact space

- Sigma-compact

- Menger space

- Hurewicz space

- Rothberger space

References

- ↑ Menger, Karl (1924). "Einige Überdeckungssätze der Punktmengenlehre". Sitzungsberichte der Wiener Akademie 133: 421–444. Reprinted in Selecta Mathematica I (2002), doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-6110-4_14, ISBN 978-3-7091-7282-7, pp. 155-178.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hurewicz, Witold (1926). "Über eine verallgemeinerung des Borelschen Theorems". Mathematische Zeitschrift 24 (1): 401–421. doi:10.1007/bf01216792.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Scheepers, Marion (1996). "Combinatorics of open covers I: Ramsey theory". Topology and Its Applications 69: 31–62. doi:10.1016/0166-8641(95)00067-4.

- ↑ Kocinac, Ljubisa D. R. (2015). "Star selection principles: a survey". Khayyam Journal of Mathematics 1: 82–106. http://emis.de/journals/KJM/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Just, Winfried; Miller, Arnold; Scheepers, Marion; Szeptycki, Paul (1996). "Combinatorics of open covers II". Topology and Its Applications 73 (3): 241–266. doi:10.1016/S0166-8641(96)00075-2.

- ↑ Scheepers, Marion (1995-01-01). "A direct proof of a theorem of Telgársky". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 123 (11): 3483–3485. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1995-1273523-1. ISSN 0002-9939.

- ↑ Telgársky, Rastislav (1984-06-01). "On games of Topsoe.". Mathematica Scandinavica 54: 170–176. doi:10.7146/math.scand.a-12050. ISSN 1903-1807.

- ↑ Steven, Clontz (2017-07-31). "Applications of limited information strategies in Menger's game". Commentationes Mathematicae Universitatis Carolinae (Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press) 58 (2): 225–239. doi:10.14712/1213-7243.2015.201. ISSN 0010-2628.

- ↑ Pawlikowski, Janusz (1994). "Undetermined sets of point-open games". Fundamenta Mathematicae 144 (3): 279–285. doi:10.4064/fm-144-3-279-285. ISSN 0016-2736. https://eudml.org/doc/212029.

- ↑ Jordan, Francis (2020). "On the instability of a topological game related to consonance". Topology and Its Applications (Elsevier BV) 271. doi:10.1016/j.topol.2019.106990. ISSN 0166-8641.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Rothberger, Fritz (1938). "Eine Verschärfung der Eigenschaft C". Fundamenta Mathematicae 30: 50–55. doi:10.4064/fm-30-1-50-55. http://pldml.icm.edu.pl/pldml/element/bwmeta1.element.bwnjournal-article-fmv30i1p8bwm?q=bwmeta1.element.bwnjournal-number-fm-1938-30-1;7&qt=CHILDREN-STATELESS.

- ↑ Hurewicz, Witold (1927). "Über Folgen stetiger Funktionen". Fundamenta Mathematicae 9: 193–210. doi:10.4064/fm-9-1-193-210. http://pldml.icm.edu.pl/pldml/element/bwmeta1.element.bwnjournal-article-fmv9i1p17bwm?q=bwmeta1.element.bwnjournal-number-fm-1927-9-1;16&qt=CHILDREN-STATELESS.

- ↑ Fremlin, David; Miller, Arnold (1988). "On some properties of Hurewicz, Menger and Rothberger". Fundamenta Mathematicae 129: 17–33. doi:10.4064/fm-129-1-17-33. http://matwbn.icm.edu.pl/ksiazki/fm/fm129/fm12913.pdf.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Recław, Ireneusz (1994). "Every Lusin set is undetermined in the point-open game". Fundamenta Mathematicae 144: 43–54. doi:10.4064/fm-144-1-43-54. http://pldml.icm.edu.pl/pldml/element/bwmeta1.element.bwnjournal-article-fmv144i1p43bwm?q=bwmeta1.element.bwnjournal-number-fm-1994-144-1;3&qt=CHILDREN-STATELESS.

- ↑ Aurichi, Leandro (2010). "D-Spaces, Topological Games, and Selection Principles". Topology Proceedings 36: 107–122. http://topology.auburn.edu/tp/reprints/v36/tp36009.pdf.

- ↑ Szewczak, Piotr; Tsaban, Boaz (2016). "Product of Menger spaces, II: general spaces". arXiv:1607.01687 [math.GN].

- ↑ Galvin, Fred; Miller, Arnold (1984). "-sets and other singular sets of real numbers". Topology and Its Applications 17 (2): 145–155. doi:10.1016/0166-8641(84)90038-5.

- ↑ Gerlits, J.; Nagy, Zs. (1982). "Some properties of , I". Topology and Its Applications 14 (2): 151–161. doi:10.1016/0166-8641(82)90065-7.

- ↑ Sakai, Masami (1988). "Property and function spaces". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 104 (9): 917–919. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-97-03897-5.

- ↑ Arhangel'skii, Alexander (1986). "Hurewicz spaces, analytic sets and fan-tightness of spaces of functions". Soviet Math. Dokl. 2: 396–399.

|