Social:Akkala Sámi

Akkala Sámi, also referred to, particularly in Russia, as Babin Sámi (Russian: Бабинский саа́мский), was a Sámi language spoken in the Sámi villages of Aʼkkel (Russian: Бабинский; Finnish: Akkala), Čuʼkksuâl (Russian: Экостровский) and Sââʼrvesjäuʼrr (Russian: Гирвасозеро; Finnish: Hirvasjärvi), in the inland parts of the Kola Peninsula in Russia . Formerly erroneously[according to whom?] regarded as a dialect of Kildin Sámi, it has recently[when?] become recognized as an independent Sámi language that is most closely related to its western neighbor Skolt Sámi.[citation needed]

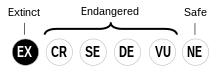

Akkala Sámi was noted as extinct in the 2010 UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. Previously, it had been considered the most endangered Eastern Sámi language. On December 29, 2003, Maria Sergina – the last fluent native speaker of Akkala Sámi – died.[4][5] However, as of 2011 there were at least two people, both aged 70, with some knowledge of Akkala Sámi. Remaining ethnic Akkala Sámi live in the village Yona.[6]

Although there exists a description of Akkala Sámi phonology and morphology, a few published texts, and archived audio recordings,[6] the Akkala Sámi language remains among the most poorly documented Sámi languages.[6] One of the few items in the language are chapters 23–28 of the Gospel of Matthew published in 1897. It was translated by A. Genetz, and printed at the expense of the British and Foreign Bible Society.[citation needed]

In the Russian 2020 census, 1 person still claimed knowledge of Akkala.[7]

Morphology

The following overview is based on Pekka (Pyotr) M. Zaykov's volume.[8] Zaykov's Uralic phonetic transcription is retained here. The middle dot ˑ denotes palatalization of the preceding consonant, analyzed by Zaykov as semisoft pronunciation.

Noun

Akkala Sámi has eight cases, singular and plural: nominative, genitive-accusative, partitive, dative-illative, locative, essive, comitative and abessive. Case and number are expressed by a combination of endings and consonant gradation:

- Nominative: no marker in the singular, weak grade in the plural.

- Genitive-accusative: weak grade in the singular, weak grade + -i in the plural.

- Partitive: this case exists only in the singular, and has the ending -tti͔.

- Dative-illative: strong grade + -a, -a͕ or -ɛ in the singular, weak grade + -i in the plural.

- Locative: weak grade + -st, -śtˑ in the singular, weak grade + -nˑ in the plural.

- Essive: this case exists only in the singular: strong grade + -nˑ.

- Comitative: weak grade + -nˑ in the singular, strong grade + -guim, -vuim or -vi̮i̭m in the plural.

- Abessive: weak grade + -ta in the singular.

Pronoun

The table below gives the declension of the personal pronouns monn ‘I’ and mij ‘we’. The pronouns tonn ‘you (sg.)’ and sonn ‘(s)he’ are declined like monn, the pronouns tij ‘you (pl.)’ and sij ‘they’ are declined like mij.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | monn | mij |

| Genitive-Accusative | mū | mii̭ji |

| Essive | munˑ | --- |

| Dative-illative | munˑnˑa͔ | mii̭ji |

| Locative | muśtˑ | miśtˑ |

| Comitative | muinˑ | mii̭jivuim |

| Abessive | muta | mii̭ta |

The interrogative pronouns mī ‘what?’ and tˑī, kī ‘who?’ are declined as follows:

| mī ‘what?’ | tˑī, kī ‘who?’ | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | mī | tˑī, kī |

| Genitive-Accusative | mi̮n | t́an, ḱan |

| Dative-illative | mi̮z | koz |

| Locative | mi̮st | kośtˑ |

| Comitative | mi̮i̭nˑ | ḱainˑ |

| Abessive | mi̮nta | ḱanta |

The proximal demonstrative tˑa͕t ‘this’ and the medial demonstrative ti̮t ‘that’ are declined as follows:

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | tˑa͕t | tˑa͕k | ti̮t | ti̮k |

| Genitive-Accusative | tˑa͕nˑ | tˑa͕i | ti̮n | ti̮i̭ |

| Essive | tˑa͕inˑ | --- | ti̮i̭nˑ | --- |

| Dative-illative | tˑa͕z | tˑai(t) | ti̮k, ti̮z | ti̮i̭(t) |

| Locative | tˑa͕śtˑ | tˑa͕in | ti̮śtˑ | ti̮i̼(n) |

| Comitative | tˑa͕inˑ | tˑa͕ivuim | ti̮i̭nˑ | ti̮i̭vuim |

| Abessive | tˑa͕ta | tˑa͕ita | ti̮ta | ti̮i̭ta |

Verb

Akkala Sámi verbs have three persons and two numbers, singular and plural. There are three moods: indicative, imperative and conditional; the potential mood has disappeared. Below, the paradigm of the verbs va͕n̄ˑće ‘to walk’ and korrɛ ‘to knit’ is given in the present and imperfect tense:

| Present | Imperfect | Present | Imperfect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1sg. | vā͕nʒam | va͕n̄ˑcim | kōram | korri͔m |

| 2sg. | va͕nʒak | vā͕nˑcik | kōrak | korri͔k |

| 3sg. | va͕n̄ˑc | vānˑʒi | korr | kōri͔ |

| 1pl. | va͕n̄ˑćepˑ | vānˑʒim | korrɛpˑ | kōri͔m |

| 2pl. | va͕nˑćepˑpˑe | vānˑʒitˑ | korrɛpˑpˑe | kōri͔tˑ |

| 3pl. | vā͕nˑʒatˑ | van̄ˑciš | kōratˑ | korri͔š |

The verb ĺiije ‘to be’ conjugates as follows:

| Present | Imperfect | |

|---|---|---|

| 1sg. | ĺam | ĺii̭jim |

| 2sg. | ĺak | ĺiijik |

| 3sg. | ĺie | ĺai |

| 1pl. | ĺepˑ | ĺījim |

| 2pl. | ĺepˑpˑe | ĺījitˑ |

| 3pl. | ĺetˑ | ĺii̭jiš |

Compound tenses such as perfect and pluperfect are formed with the verb ĺii̭je in the present or imperfect as auxiliary, and the participle of the main verb. Examples are ĺam tĭĕhtmi̮nč ‘I have known’ from tĭĕhttɛ ‘to know’, and ĺai tui̭jāma ‘(s)he had made’ from tui̭je ‘to make’.

The conditional mood has the marker -č, which is added to the weak grade of the stem: kuarčim ‘I would sew’, vizzčik ‘you (sg.) would become tired’.

As in other Sámi languages, Akkala Sámi makes use of a negative verb that conjugates according to person and number, while the main verb remains unchanged. The conjugation of the negative verb is shown here together with the verb aĺ̄ḱe ‘to begin’:

| 1sg. | jim aĺg |

| 2sg. | jik aĺg |

| 3sg. | ij aĺg |

| 1pl. | jepˑ aĺg |

| 2pl. | jepˑpˑe aĺg |

| 3pl. | jetˑ aĺg |

The third person singular and plural of the verb ĺii̭je ‘to be’ have special contracted forms ɛĺĺa and jāĺa.

References

- ↑ Akkala Sámi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Akkala Saami". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/akka1237.

- ↑ Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (Report) (3rd ed.). UNESCO. 2010. p. 7. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026.

- ↑ "Nordisk samekonvensjon" (in sv). http://www.galdu.org/govat/doc/nordisk_samekonvensjon.pdf.

- ↑ Rantala, Leif, Aleftina Sergina 2009. Áhkkila sápmelaččat. Oanehis muitalus sámejoavkku birra, man maŋimuš sámegielalaš olmmoš jámii 29.12.2003. Roavvenjárga.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 Scheller, Elizabeth (2011). "The Sámi Language Situation in Russia". in Grünthal, Riho; Kovács, Magdolna. Ethnic and Linguistic Context of Identity: Finno-Ugric Minorities. Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki, Department of Finnish, Finno-Ugrian and Scandinavian Studies. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-952-5667-28-8. OCLC 755168782. https://munin.uit.no/bitstream/handle/10037/5123/article.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- ↑ "Росстат — Всероссийская перепись населения 2020". https://rosstat.gov.ru/vpn_popul.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Зайков, П. М. Бабинский диалект саамского языка (фонолого-морфологическое исследование). Петрозаводск: «Карелия», 1987.

External links

|