Social:History of human thought

History of human thought spans across the history of humanity. It covers the history of philosophy, history of science, history of political thought, and history of science, among others. The discipline studying it is called intellectual history.[1]

Merlin Donald has claimed that human thought has progressed through three historic stages: the episodic, the mimetic, and the mythic stages, before reaching the current stage of theoretic thinking or culture.[2] According to him the final transition occurred with the invention of science in Ancient Greece.[3]

Prehistoric human thought

Prehistory cover human intellectual history before the invention of writing.

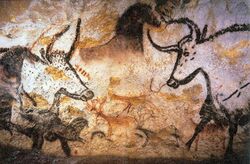

The first identified cultures are from the Upper Paleolithic era, evidenced by regional patterns in artefacts such as cave art, Venus figurines, and stone tools[4] The Aterian culture was engaged in symbolically constituted material culture, creating what are amongst the earliest African examples of personal ornamentation.[5]

Origins of religion

The Natufian culture of ancient Middle East produced zoomorphic art.[6] The Khiamian culture which followed moved into depicting human beings, which was called by Jacques Cauvin a "revolution in symbols", becoming increasingly realistic.[7] According to him, this lead to the development of religion, with the Woman and the Bull as the first sacred figures.[6] He claims that this led to a revolution in human thinking, with humans for the first time moving from animal or spirit worship to the worship of a supreme being, with humans clearly in hierarchical relation to it.[8] Another early form of religion has been identified by Marija Gimbutas as the worship of the Great Goddess, the Bird or Snake Goddess, the Vegetation Goddess, and the Male God in Old Europe.[9]

An important innovation in religious thought was the invention of the sky god.[10] The Aryans had a common god of the sky called Dyeus, and the Indian Dyaus, the Greek Zeus, and the Roman Jupiter were all further developments, with the Latin word for God being Deus.[10] Any masculine sky god is often also king of the gods, taking the position of patriarch within a pantheon. Such king gods are collectively categorized as "sky father" deities, with a polarity between sky and earth often being expressed by pairing a "sky father" god with an "earth mother" goddess (pairings of a sky mother with an earth father are less frequent). A main sky goddess is often the queen of the gods. In antiquity, several sky goddesses in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Near East were called Queen of Heaven.

Ancient thought

Axial age

The Axial Age was a period between 750 and 350 BCE during which major intellectual development happened around the world. This included the development of Chinese philosophy by Confucius, Mozi, and others; the Upanishads and Gautama Buddha in Indian philosophy; Zoroaster in Persia; the prophets Elijah, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Deutero-Isaiah in Palestine; Ancient Greek philosophy and literature, all independently of each other.[11]

Ancient Chinese thought

The Hundred Schools of Thought were philosophers and schools of thought that flourished from the 6th century to 221 BCE,[12] an era of great cultural and intellectual expansion in China. Even though this period – known in its earlier part as the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period – in its latter part was fraught with chaos and bloody battles, it is also known as the Golden Age of Chinese philosophy because a broad range of thoughts and ideas were developed and discussed freely. The thoughts and ideas discussed and refined during this period have profoundly influenced lifestyles and social consciousness up to the present day in East Asian countries. The intellectual society of this era was characterized by itinerant scholars, who were often employed by various state rulers as advisers on the methods of government, war, and diplomacy. This period ended with the rise of the Qin Dynasty and the subsequent purge of dissent. The Book of Han lists ten major schools, they are:

- Confucianism, which teaches that human beings are teachable, improvable and perfectible through personal and communal endeavour especially including self-cultivation and self-creation. A main idea of Confucianism is the cultivation of virtue and the development of moral perfection. Confucianism holds that one should give up one's life, if necessary, either passively or actively, for the sake of upholding the cardinal moral values of ren and yi.[13]

- Legalism. Often compared with Machiavelli, and foundational for the traditional Chinese bureaucratic empire, the Legalists examined administrative methods, emphasizing a realistic consolidation of the wealth and power of autocrat and state.

- Taoism, a philosophy which emphasizes the Three Jewels of the Tao: compassion, moderation, and humility, while Taoist thought generally focuses on nature, the relationship between humanity and the cosmos; health and longevity; and wu wei (action through inaction). Harmony with the Universe, or the source thereof (Tao), is the intended result of many Taoist rules and practices.

- Mohism, which advocated the idea of universal love: Mozi believed that "everyone is equal before heaven", and that people should seek to imitate heaven by engaging in the practice of collective love. His epistemology can be regarded as primitive materialist empiricism; he believed that human cognition ought to be based on one's perceptions – one's sensory experiences, such as sight and hearing – instead of imagination or internal logic, elements founded on the human capacity for abstraction. Mozi advocated frugality, condemning the Confucian emphasis on ritual and music, which he denounced as extravagant.

- Naturalism, the School of Naturalists or the Yin-yang school, which synthesized the concepts of yin and yang and the Five Elements; Zou Yan is considered the founder of this school.[14]

- Agrarianism, or the School of Agrarianism, which advocated peasant utopian communalism and egalitarianism.[15] The Agrarians believed that Chinese society should be modeled around that of the early sage king Shen Nong, a folk hero which was portrayed in Chinese literature as "working in the fields, along with everyone else, and consulting with everyone else when any decision had to be reached."[15]

- The Logicians or the School of Names, which focused on definition and logic. It is said to have parallels with that of the Ancient Greek sophists or dialecticians. The most notable Logician was Gongsun Longzi.

- The School of Diplomacy or School of Vertical and Horizontal [Alliances], which focused on practical matters instead of any moral principle, so it stressed political and diplomatic tactics, and debate and lobbying skill. Scholars from this school were good orators, debaters and tacticians.

- The Miscellaneous School, which integrated teachings from different schools; for instance, Lü Buwei found scholars from different schools to write a book called Lüshi Chunqiu cooperatively. This school tried to integrate the merits of various schools and avoid their perceived flaws.

- The School of "Minor-talks", which was not a unique school of thought, but a philosophy constructed of all the thoughts which were discussed by and originated from normal people on the street.

Other groups included:

- The School of the Military that studied strategy and the philosophy of war; Sunzi and Sun Bin were influential leaders. However, this school was not one of the "Ten Schools" defined by Hanshu.

- Yangism was a form of ethical egoism founded by Yang Zhu. It was once widespread but fell to obscurity before the Han dynasty. Due to its stress on individualism, it influenced later generations of Taoists.

- School of the Medical Skills, a school which studied Medicine and health. Bian Que and Qibo were well-known scholars. Two of the earliest and existing Chinese medical works are Huangdi Neijing and Shanghan Lun.

Ancient Greek thought

Pre-Socratics

The earliest Greek philosophers were called the pre-Socratics, as they were primarily concerned with cosmology, ontology, and mathematics. They were distinguished from "non-philosophers" insofar as they rejected mythological explanations in favor of reasoned discourse.[16] They included various schools of thought:

- The Milesian school of philosophy was founded by Thales of Miletus, regarded by Aristotle as the first philosopher,[17] who held that all things arise from a single material substance, water.[18] He was called the "first man of science," because he gave a naturalistic explanation of the cosmos and supported it with reasons.[19] He was followed by Anaximander, who argued that the substratum or arche could not be water or any of the classical elements but was instead something "unlimited" or "indefinite" (in Greek, the apeiron). Anaximenes in turn held that the arche was air, although John Burnet argues that by this he meant that it was a transparent mist, the aether.[20] Despite their varied answers, the Milesian school was united in looking for the Physis of the world.[21]

- Pythagoreanism was founded by Pythagoras and sought to reconcile religious belief and reason. He is said to have been a disciple of Anaximander and to have imbibed the cosmological concerns of the Ionians, including the idea that the cosmos is constructed of spheres, the importance of the infinite, and that air or aether is the arche of everything.[22] Pythagoreanism also incorporated ascetic ideals, emphasizing purgation, metempsychosis, and consequently a respect for all animal life; much was made of the correspondence between mathematics and the cosmos in a musical harmony.[23] Pythagoras believed that behind the appearance of things, there was the permanent principle of mathematics, and that the forms were based on a transcendental mathematical relation.[24]

- The Ephesian school was based on the thought of Heraclitus. Contrary to the Milesian school, which posits one stable element as the arche, Heraclitus taught that panta rhei ("everything flows"), the closest element to this eternal flux being fire. All things come to pass in accordance with Logos,[25] which must be considered as "plan" or "formula",[26] and "the Logos is common".[27] He also posited a unity of opposites, expressed through dialectic, which structured this flux, such as that seeming opposites in fact are manifestations of a common substrate to good and evil itself.[28]Heraclitus called the oppositional processes ἔρις (eris), "strife", and hypothesized that the apparently stable state of δίκη (dikê), or "justice", is the harmonic unity of these opposites.[29]

- The Eleatics' founder Parmenides of Elea cast his philosophy against those who held "it is and is not the same, and all things travel in opposite directions,"—presumably referring to Heraclitus and those who followed him.[30] Whereas the doctrines of the Milesian school, in suggesting that the substratum could appear in a variety of different guises, implied that everything that exists is corpuscular, Parmenides argued that the first principle of being was One, indivisible, and unchanging.[31] Being, he argued, by definition implies eternality, while only that which is can be thought; a thing which is, moreover, cannot be more or less, and so the rarefaction and condensation of the Milesians is impossible regarding Being; lastly, as movement requires that something exist apart from the thing moving (viz. the space into which it moves), the One or Being cannot move, since this would require that "space" both exist and not exist.[32] While this doctrine is at odds with ordinary sensory experience, where things do indeed change and move, the Eleatic school followed Parmenides in denying that sense phenomena revealed the world as it actually was; instead, the only thing with Being was thought, or the question of whether something exists or not is one of whether it can be thought.[33] In support of this, Parmenides' pupil Zeno of Elea attempted to prove that the concept of motion was absurd and as such motion did not exist. He also attacked the subsequent development of pluralism, arguing that it was incompatible with Being.[34] His arguments are known as Zeno's paradoxes.

- The Pluralist school came as the power of Parmenides' logic was such that some subsequent philosophers abandoned the monism of the Milesians, Xenophanes, Heraclitus, and Parmenides, where one thing was the arche, and adopted pluralism, such as Empedocles and Anaxagoras.[35] There were, they said, multiple elements which were not reducible to one another and these were set in motion by love and strife (as in Empedocles) or by Mind (as in Anaxagoras). Agreeing with Parmenides that there is no coming into being or passing away, genesis or decay, they said that things appear to come into being and pass away because the elements out of which they are composed assemble or disassemble while themselves being unchanging.[36]

- Thes pluralist thought was taken further by Leucippus also proposed an ontological pluralism with a cosmogony based on two main elements: the vacuum and atoms. These, by means of their inherent movement, are crossing the void and creating the real material bodies. His theories were not well known by the time of Plato, however, and they were ultimately incorporated into the work of his student, Democritus, who founded Atomic theory.[37]

- The Sophists tended to teach rhetoric as their primary vocation. Prodicus, Gorgias, Hippias, and Thrasymachus appear in various dialogues, sometimes explicitly teaching that while nature provides no ethical guidance, the guidance that the laws provide is worthless, or that nature favors those who act against the laws.

Classic period

The classic period included:

- The Cynics were an ascetic sect of philosophers beginning with Antisthenes in the 4th century BC and continuing until the 5th century AD. They believed that one should live a life of Virtue in agreement with Nature. This meant rejecting all conventional desires for wealth, power, health, or celebrity, and living a life free from possessions.

- The Cyrenaics were a hedonist school of philosophy founded in the fourth century BC by Aristippus, who was a student of Socrates. They held that pleasure was the supreme good, especially immediate gratifications; and that people could only know their own experiences, beyond that truth was unknowable.

- Platonism is the name given to the philosophy of Plato, which was maintained and developed by his followers. The central concept was the theory of forms: the transcendent, perfect archetypes, of which objects in the everyday world are imperfect copies. The highest form was the Form of the Good, the source of being, which could be known by reason.

- The Peripatetic school was the name given to the philosophers who maintained and developed the philosophy of Aristotle. They advocated examination of the world to understand the ultimate foundation of things. The goal of life was the happiness which originated from virtuous actions, which consisted in keeping the mean between the two extremes of the too much and the too little.

- The Megarian school, founded by Euclides of Megara, one of the pupils of Socrates. Its ethical teachings were derived from Socrates, recognizing a single good, which was apparently combined with the Eleatic doctrine of Unity. Some of Euclides' successors developed logic to such an extent that they became a separate school, known as the Dialectical school. Their work on modal logic, logical conditionals, and propositional logic played an important role in the development of logic in antiquity.

- The Eretrian school, founded by Phaedo of Elis. Like the Megarians they seem to have believed in the individuality of "the Good," the denial of the plurality of virtue, and of any real difference existing between the Good and the True. Cicero tells us that they placed all good in the mind, and in that acuteness of mind by which the truth is discerned.[38] They denied that truth could be inferred by negative categorical propositions, and would only allow positive ones, and of these only simple ones.[39]

Hellenistic schools of thought

The Hellenistic schools of thought included:

- Academic skepticism, which maintained that knowledge of things is impossible. Ideas or notions are never true; nevertheless, there are degrees of truth-likeness, and hence degrees of belief, which allow one to act. The school was characterized by its attacks on the Stoics and on the Stoic dogma that convincing impressions led to true knowledge.

- Eclecticism,a system of philosophy which adopted no single set of doctrines but selected from existing philosophical beliefs those doctrines that seemed most reasonable. Its most notable advocate was Cicero.

- Epicureanism, founded by Epicurus in the 3rd century BC. It viewed the universe as being ruled by chance, with no interference from gods. It regarded absence of pain as the greatest pleasure, and advocated a simple life. It was the main rival to Stoicism until both philosophies died out in the 3rd century AD.

- Hellenistic Christianity was the attempt to reconcile Christianity with Greek philosophy, beginning in the late 2nd century. Drawing particularly on Platonism and the newly emerging Neoplatonism, figures such as Clement of Alexandria sought to provide Christianity with a philosophical framework.

- Hellenistic Judaism was an attempt to establish the Jewish religious tradition within the culture and language of Hellenism. Its principal representative was Philo of Alexandria.

- Neoplatonism, or Plotinism, a school of religious and mystical philosophy founded by Plotinus in the 3rd century AD and based on the teachings of Plato and the other Platonists. The summit of existence was the One or the Good, the source of all things. In virtue and meditation the soul had the power to elevate itself to attain union with the One, the true function of human beings.

- Neopythagoreanism, a school of philosophy reviving Pythagorean doctrines, which was prominent in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. It was an attempt to introduce a religious element into Greek philosophy, worshipping God by living an ascetic life, ignoring bodily pleasures and all sensuous impulses, to purify the soul.

- Pyrrhonism, a school of philosophical skepticism that originated with Pyrrho in the 3rd century BC, and was further advanced by Aenesidemus in the 1st century BC. Its objective is ataraxia (being mentally unperturbed), which is achieved through epoché (i.e. suspension of judgment) about non-evident matters (i.e., matters of belief).

- Stoicism, founded by Zeno of Citium in the 3rd century BC. Based on the ethical ideas of the Cynics, it taught that the goal of life was to live in accordance with Nature. It advocated the development of self-control and fortitude as a means of overcoming destructive emotions.

Indian philosophy

Orthodox schools

Many Hindu intellectual traditions were classified during the medieval period of Brahmanic-Sanskritic scholasticism into a standard list of six orthodox (Astika) schools (darshanas), the "Six Philosophies" (ṣaḍ-darśana), all of which accept the testimony of the Vedas.[40][41][42]

- Samkhya, the rationalism school with dualism and atheistic themes[43][44]

- Yoga, a school similar to Samkhya but accepts personally defined theistic themes[45]

- Nyaya, the realism school emphasizing analytics and logic[46][47]

- Vaisheshika, the naturalism school with atomistic themes and related to the Nyaya school[48][49]

- Purva Mimamsa (or simply Mimamsa), the ritualism school with Vedic exegesis and philology emphasis,[50][51] and

- Vedanta (also called Uttara Mimamsa), the Upanishadic tradition, with many sub-schools ranging from dualism to nondualism.[52][53]

These are often coupled into three groups for both historical and conceptual reasons: Nyaya-Vaishesika, Samkhya-Yoga, and Mimamsa-Vedanta. The Vedanta school is further divided into six sub-schools: Advaita (monism/nondualism), also includes the concept of Ajativada, Visishtadvaita (monism of the qualified whole), Dvaita (dualism), Dvaitadvaita (dualism-nondualism), Suddhadvaita, and Achintya Bheda Abheda schools.

Heterodox schools

Several Śramaṇic movements have existed before the 6th century BCE, and these influenced both the āstika and nāstika traditions of Indian philosophy.[54] The Śramaṇa movement gave rise to diverse range of heterodox beliefs, ranging from accepting or denying the concept of soul, atomism, antinomian ethics, materialism, atheism, agnosticism, fatalism to free will, idealization of extreme asceticism to that of family life, strict ahimsa (non-violence) and vegetarianism to permissibility of violence and meat-eating.[55] Notable philosophies that arose from Śramaṇic movement were Jainism, early Buddhism, Charvaka, Ajñana and Ājīvika.[56]

- Ajñana was one of the nāstika or "heterodox" schools of ancient Indian philosophy, and the ancient school of radical Indian skepticism. It was a Śramaṇa movement and a major rival of early Buddhism and Jainism. They have been recorded in Buddhist and Jain texts. They held that it was impossible to obtain knowledge of metaphysical nature or ascertain the truth value of philosophical propositions; and even if knowledge was possible, it was useless and disadvantageous for final salvation. They were sophists who specialised in refutation without propagating any positive doctrine of their own.

- Jain philosophy is the oldest Indian philosophy that separates body (matter) from the soul (consciousness) completely.[57] Jainism was established by Mahavira, the last and the 24th Tirthankara. Historians date the Mahavira as about contemporaneous with the Buddha in the 5th-century BC, and accordingly the historical Parshvanatha, based on the c. 250-year gap, is placed in 8th or 7th century BC.[58] Jainism is a Śramaṇic religion and rejected the authority of the Vedas. However, like all Indian religions, it shares the core concepts such as karma, ethical living, rebirth, samsara and moksha. Jainism places strong emphasis on asceticism, ahimsa (non-violence) and anekantavada (relativity of viewpoints) as a means of spiritual liberation, ideas that influenced other Indian traditions.[59] Jainism strongly upholds the individualistic nature of soul and personal responsibility for one's decisions; and that self-reliance and individual efforts alone are responsible for one's liberation. According to the Jain philosophy, the world (Saṃsāra) is full of hiṃsā (violence). Therefore, one should direct all his efforts in attainment of Ratnatraya, that are Samyak Darshan, Samyak Gnana, and Samyak Chàritra which are the key requisites to attain liberation.

- Buddhist philosophy is a system of thought which started with the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, or "awakened one". Buddhism is founded on elements of the Śramaṇa movement, which flowered in the first half of the 1st millennium BCE, but its foundations contain novel ideas not found or accepted by other Sramana movements. Buddhism shares many philosophical views with other Indian systems, such as belief in karma – a cause-and-effect relationship, samsara – ideas about cyclic afterlife and rebirth, dharma – ideas about ethics, duties and values, impermanence of all material things and of body, and possibility of spiritual liberation (nirvana or moksha).[60][61] A major departure from Hindu and Jain philosophy is the Buddhist rejection of an eternal soul (atman) in favour of anatta (non-Self).[62]

- The philosophy of Ājīvika was founded by Makkhali Gosala, it was a Śramaṇa movement and a major rival of early Buddhism and Jainism.[63] Ājīvikas were organised renunciates who formed discrete monastic communities prone to an ascetic and simple lifestyle.[64] Original scriptures of the Ājīvika school of philosophy may once have existed, but these are currently unavailable and probably lost. The Ājīvika school is known for its Niyati doctrine of absolute determinism (fate), the premise that there is no free will, that everything that has happened, is happening and will happen is entirely preordained and a function of cosmic principles.[65][66] Ājīvika considered the karma doctrine as a fallacy.[67] Ājīvikas were atheists[68] and rejected the authority of the Vedas, but they believed that in every living being is an ātman – a central premise of Hinduism and Jainism.[69][70]

- Charvaka or Lokāyata was a philosophy of scepticism and materialism, founded in the Mauryan period. They were extremely critical of other schools of philosophy of the time. Charvaka deemed Vedas to be tainted by the three faults of untruth, self-contradiction, and tautology.[71] Likewise they faulted Buddhists and Jains, mocking the concept of liberation, reincarnation and accumulation of merit or demerit through karma.[72] They believed that, the viewpoint of relinquishing pleasure to avoid pain was the "reasoning of fools".[71]

Similarities between Greek and Indian thought

- Several scholars have recognised parallels between the philosophy of Pythagoras and Plato and that of the Upanishads, including their ideas on sources of knowledge, concept of justice and path to salvation, and Plato's allegory of the cave. Platonic psychology with its divisions of reason, spirit and appetite, also bears resemblance to the three gunas in the Indian philosophy of Samkhya.[73][74]

Various mechanisms for such a transmission of knowledge have been conjectured including Pythagoras traveling as far as India; Indian philosophers visiting Athens and meeting Socrates; Plato encountering the ideas when in exile in Syracuse; or, intermediated through Persia.[73][75]

However, other scholars, such as Arthur Berriedale Keith, J. Burnet and A. R. Wadia, believe that the two systems developed independently. They note that there is no historical evidence of the philosophers of the two schools meeting, and point out significant differences in the stage of development, orientation and goals of the two philosophical systems. Wadia writes that Plato's metaphysics were rooted in this life and his primary aim was to develop an ideal state.[74] In contrast, Upanishadic focus was the individual, the self (atman, soul), self-knowledge, and the means of an individual's moksha (freedom, liberation in this life or after-life).[76][77]

Persian philosophy

- Zoroastrianism, based on the teachings of Zarathustra (Zoroaster) appeared in Persia at some point during the period 1700-1800 BCE.[78][79] His wisdom became the basis of the religion Zoroastrianism, and generally influenced the development of the Iranian branch of Indo-Iranian philosophy. Zarathustra was the first who treated the problem of evil in philosophical terms.[79] He is also believed to be one of the oldest monotheists in the history of religion[citation needed]. He espoused an ethical philosophy based on the primacy of good thoughts (andiše-e-nik), good words (goftâr-e-nik), and good deeds (kerdâr-e-nik). The works of Zoroaster and Zoroastrianism had a significant influence on Greek philosophy and Roman philosophy. Several ancient Greek writers such as Eudoxus of Cnidus and Latin writers such as Pliny the Elder praised Zoroastrian philosophy as "the most famous and most useful"[citation needed]. Plato learnt of Zoroastrian philosophy through Eudoxus and incorporated much of it into his own Platonic realism.[80] In the 3rd century BC, however, Colotes accused Plato's The Republic of plagiarizing parts of Zoroaster's On Nature, such as the Myth of Er.[81][82]

- Manichaeism, founded by Mani, was influential from North Africa in the West, to China in the East. Its influence subtly continues in Western Christian thought via Saint Augustine of Hippo, who converted to Christianity from Manichaeism, which he passionately denounced in his writings, and whose writings continue to be influential among Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox theologians. An important principle of Manichaeism was its dualistic cosmology/theology, which it shared with Mazdakism, a philosophy founded by Mazdak. Under this dualism, there were two original principles of the universe: Light, the good one; and Darkness, the evil one. These two had been mixed by a cosmic accident, and man's role in this life was through good conduct to release the parts of himself that belonged to Light. Mani saw the mixture of good and bad as a cosmic tragedy, while Mazdak viewed this in a more neutral, even optimistic way. Mazdak (d. 524/528 CE) was a proto-socialist Persian reformer who gained influence under the reign of the Sassanian king Kavadh I. He claimed to be a prophet of God, and instituted communal possessions and social welfare programs. In many ways Mazdak's teaching can be understood as a call for social revolution, and has been referred to as early "communism"[83] or proto-socialism.[84]

- Zurvanism is characterized by the element of its First Principle which is Time, "Zurvan", as a primordial creator. According to Zaehner, Zurvanism appears to have three schools of thought all of which have classical Zurvanism as their foundation:Aesthetic Zurvanism which was apparently not as popular as the materialistic kind, viewed Zurvan as undifferentiated Time, which, under the influence of desire, divided into reason (a male principle) and concupiscence (a female principle). While Zoroaster's Ormuzd created the universe with his thought, materialist Zurvanism challenged the concept that anything could be made out of nothing. Fatalistic Zurvanism resulted from the doctrine of limited time with the implication that nothing could change this preordained course of the material universe and that the path of the astral bodies of the 'heavenly sphere' was representative of this preordained course. According to the Middle Persian work Menog-i Khrad: "Ohrmazd allotted happiness to man, but if man did not receive it, it was owing to the extortion of these planets."

Modern period

Europe

The modern intellectual history of Europe cannot be separated from various bodies of ancient thought, from the works of classical Greek and Latin authors to the writings of the fathers of the Christian Church. Such a broad survey of topics is not attempted here, however. A debatable but defensible starting point for modern European thought might instead be identified with the birth of scholasticism and humanism in the 13th and 14th centuries. Both of these intellectual currents were associated with classical revivals (in the case of scholasticism, the rediscovery of Aristotle; in the case of humanism, of Latin antiquity, especially Cicero) and with prominent founders, Aquinas and Petrarch respectively. But they were both significantly original intellectual experiences, as well as self-consciously modern, so that they make an appropriate starting point for this survey.

What follows below is a selective and far from complete listing of significant trends and individuals in the history of European thought. While movements such as the Enlightenment or Romanticism are relatively imprecise approximations, rarely taken too seriously by scholars, they are good starting points for approaching the enormous complexity of the history of Europe's intellectual heritage. It is hoped that interested readers will pursue the listed topics in greater depth by consulting the respective articles and the suggestions for further reading.

The intellectual history of western Europe and the Americas includes:

- Scholasticism: Associated especially with Aquinas and the recovery of Aristotle, a movement that was popular in universities and provided a new way of reasoning especially in law, philosophy, theology.

- Humanism: Humanists were associated with the discipline of rhetoric but they were not just orators, they also learned ancient languages, especially classical Greek and created new knowledge about the secular past. The revival of ancient literature and philosophy was of immense importance for the further development of European thought. The first humanist is considered to be Petrarch. Later exponents of note were Leonardo Bruni, Lorenzo Valla, and Erasmus of Rotterdam.

- The Renaissance: A movement in the arts and letters, it is associated particularly with humanism, but also with new trends in painting and with the efflorescence of a new courtly culture that from Italy (c.1350) spread across Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries.

- The New Philosophy: The 20th century dubbed this the Scientific Revolution, but in the 17th century, the new science was more often considered to be a new way of doing philosophy. It is associated mainly with the thought of Francis Bacon and Descartes. Other important philosophers were: Hobbes, Gassendi, Malebranche, Spinoza, Leibniz. Advances in astronomy were made by Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler and Galileo.

- The Royal Society: A secular creation of an intellectual world led by figures such as Isaac Newton, Robert Hooke, Christopher Wren, Joseph Addison, and Bishop Sprat.

- The Enlightenment: Key developments in thought included The rights of man, political representation, political economy, deism. Notable participants counted Bayle, Hume, Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, Fontenelle, the Comte de Buffon, Kant, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Moses Mendelssohn, Vico.

- The Encyclopaedists: The creation of central repositories of knowledge available to all outside of academies, including mass-market encyclopaedias and dictionaries: Diderot, Samuel Johnson, Voltaire, and Ephraim Chambers.

- Romanticism : Individual, subjective, imaginative, personal, visionary (scholarly sources Carlyle, Rousseau, Hook, and Herder).

- Post-romanticism: Reaction to naturalism, opposes external-only observations by adding internal observations (scholarly sources Comte, von Ranke).

- Modernism : Rejects Christian academic scholarly tradition (scholarly sources Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jacob Burckhardt, Charles Beard, Ferdinand de Saussure, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung).

- Pragmatism : Links the meaning of beliefs to the actions of a believer, and the truth of beliefs to success of those actions in securing a believer's goals. Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, John Dewey, F.C.S. Schiller, Richard Rorty. Originated in late nineteenth century America.

- Existentialism: Pre- and post-WW2 rejection of Western norms and cultural values. Søren Kierkegaard, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Hannah Arendt, Hans Jonas, Karl Löwith, Herbert Marcuse, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Martin Buber, Edmund Husserl. Engaged with the intellectual prominence of fascism and socialism in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s, which they saw needed both repudiation and study, as a way to re-establish the individual against the values of a hostile and destructive series of communities creating alienation, isolation, and individual meaninglessness.

- Postmodernism : Rejects Modernism, meta-narrative - multiple perspective, role of individual (scholarly sources Lyotard, Foucault, Barthes, Geertz).

- Structuralism : Many phenomena do not occur in isolation but in relation to each other (scholarly sources Geertz, Lévi-Strauss).

- Poststructuralism :Deconstruction, destabilizes the relationship between language and objects the language refers to (scholarly sources Lyotard, Derrida, Foucault).

Africa and the Middle East

The culture of the ancient Near East and eventually of much of Africa as well was modified significantly by the arrival of Islam beginning in the seventh century CE. The history of Islam has been the work of many scholars, both Muslim and non-Muslim, and including such luminaries as Ignác Goldziher, Marshall Hodgson and in more recent times Patricia Crone. Islamic culture is not a simple and unified entity. The history of Islam, like that of other religions, is a history of different interpretations and approaches to Islam. There is no a-historical Islam outside the process of historical development.

Islamic thought includes a variety of different intellectual disciplines, including theology, the study of the Qur'an, the study of Hadith, history, grammar, rhetoric and philosophy. For more information see the Islamic Golden Age.

Classical Islamic scholars and authors include:

- Ali al-Masudi

- Ibn Khaldūn

- Al-Ma'arri

- Taftazani

- Muhammad al-Bukhari

- Ibn Sina

- Ibn Rushd

- Ibn Arabi

- Ibn Hisham

- al-Tabari

Persian philosophy can be traced back as far as to Old Iranian philosophical traditions and thoughts which originated in ancient Indo-Iranian roots and were considerably influenced by Zarathustra's teachings. Throughout Iranian history and due to remarkable political and social changes such as the Macedonian, Arab and Mongol invasions of Persia a wide spectrum of schools of thoughts showed a variety of views on philosophical questions extending from Old Iranian and mainly Zoroastrianism-related traditions to schools appearing in the late pre-Islamic era such as Manicheism and Mazdakism as well as various post-Islamic schools. Iranian philosophy after Arab invasion of Persia, is characterized by different interactions with the Old Iranian philosophy, the Greek philosophy and with the development of Islamic philosophy. The Illumination School and the Transcendent Philosophy are regarded as two of the main philosophical traditions of that era in Persia.

Islam and modernity encompass the relation and compatibility between the phenomenon of modernity, its related concepts and ideas, and the religion of Islam. In order to understand the relation between Islam and modernity, one point should be made in the beginning. Similarly, modernity is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon rather than a unified and coherent phenomenon. It has historically had different schools of thoughts moving in many directions.

Intellectual movements in Iran involve the Iranian experience of modernism, through which Iranian modernity and its associated art, science, literature, poetry, and political structures have been evolving since the 19th century. Religious intellectualism in Iran develops gradually and subtly. It reached its apogee during the Persian Constitutional Revolution (1906–11). The process involved numerous philosophers, sociologists, political scientists and cultural theorists. However the associated art, cinema and poetry remained to be developed.

Modern Africa

Recent concepts about African culture include the African Renaissance and Afrocentrism. The African Renaissance is a concept popularized by South African President Thabo Mbeki who called upon the African people and nations to solve the many problems troubling the African continent. It reached its height in the late 1990s but continues to be a key part of the post-apartheid intellectual agenda in South Africa. The concept however extends well beyond intellectual life to politics and economic development.

With the rise of Afrocentrism, the push away from Eurocentrism has led to the focus on the contributions of African people and their model of world civilization and history. Afrocentrism aims to shift the focus from a perceived European-centered history to an African-centered history. More broadly, Afrocentrism is concerned with distinguishing the influence of European and Oriental peoples from African achievements.

Notable modern African intellectual include:

- Taban Lo Liyong

- Wole Soyinka

- Frantz Fanon

- Chinua Achebe

- Yusuf Bala Usman

- W. E. B. Du Bois spent his final years in Ghana

References

- ↑ "Global Intellectual History". https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?show=aimsScope&journalCode=rgih20&.

- ↑ Donald, Merlin, 1939- (1993). Origins of the Modern Mind : Three Stages in the Evolution of Culture and Cognition. Harvard U.P. pp. 215. OCLC 1035717909. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1035717909.

- ↑ Watson, Peter. (2009) [2005]. Ideas : a history : from fire to Freud. Folio Society. pp. 67. OCLC 417149155. http://worldcat.org/oclc/417149155.

- ↑ Watson, Peter. (2009) [2005]. Ideas : a history : from fire to Freud. Folio Society. pp. 68. OCLC 417149155. http://worldcat.org/oclc/417149155.

- ↑ Bouzouggar, Abdeljalil; Barton, Nick; Vanhaeren, Marian; d'Errico, Francesco; Collcutt, Simon; Higham, Tom; Hodge, Edward; Parfitt, Simon et al. (2007-06-12). "82,000-year-old shell beads from North Africa and implications for the origins of modern human behavior". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 (24): 9964–9969. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703877104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 17548808.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Watson, Peter. (2009) [2005]. Ideas : a history : from fire to Freud. Folio Society. pp. 81. OCLC 417149155. http://worldcat.org/oclc/417149155.

- ↑ Cauvin, Jacques (2008). The birth of the gods and the origins of agriculture. Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 22. ISBN 0-521-03908-8. OCLC 852497907. http://worldcat.org/oclc/852497907.

- ↑ Watson, Peter. (2009) [2005]. Ideas : a history : from fire to Freud. Folio Society. pp. 82. OCLC 417149155. http://worldcat.org/oclc/417149155.

- ↑ Watson, Peter. (2009) [2005]. Ideas : a history : from fire to Freud. Folio Society. pp. 90. OCLC 417149155. http://worldcat.org/oclc/417149155.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Watson, Peter, 1943- auteur.. Ideas : a history from fire to Freud. pp. 136. ISBN 978-0-7538-2089-6. OCLC 966150841. http://worldcat.org/oclc/966150841.

- ↑ Jaspers, Karl. (2014). The Origin and Goal of History (Routledge Revivals).. Taylor and Francis. pp. 2. ISBN 978-1-317-83261-4. OCLC 876512738. http://worldcat.org/oclc/876512738.

- ↑ "Chinese philosophy", Encyclopædia Britannica, accessed 4/6/2014

- ↑ Lo, Ping-cheung (1999), Confucian Ethic of Death with Dignity and Its Contemporary Relevance, Society of Christian Ethics, archived from the original on 16 July 2011, https://web.archive.org/web/20110716110845/http://arts.hkbu.edu.hk/~pclo/e5.pdf

- ↑ "Zou Yan". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/607826/Zou-Yan. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Deutsch, Eliot; Ronald Bontekoei (1999). A companion to world philosophies. Wiley Blackwell. p. 183.

- ↑ John Burnet, Greek Philosophy: Thales to Plato, 3rd ed. (London: A & C Black Ltd., 1920), 3–16. Scanned version from Internet Archive

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics Alpha, 983b18.

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics Alpha, 983 b6 8–11.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 3–4, 18.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 21.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 27.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 38–39.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 40–49.

- ↑ C.M. Bowra 1957 The Greek experience p. 166"

- ↑ DK B1.

- ↑ pp. 419ff., W.K.C. Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy, vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, 1962.

- ↑ DK B2.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 57–63.

- ↑ DK B80

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 64.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 66–67.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 68.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 67.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 82.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 69.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 70.

- ↑ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 94.

- ↑ Cicero, Academica, ii. 42.

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius, ii, 135.

- ↑ Flood, op. cit., p. 231–232.

- ↑ Michaels, p. 264.

- ↑ Nicholson 2010.

- ↑ Mike Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga - An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN:978-0415648875, pages 43-46

- ↑ Tom Flynn and Richard Dawkins (2007), The New Encyclopedia of Unbelief, Prometheus, ISBN:978-1591023913, pages 420-421

- ↑ Edwin Bryant (2011, Rutgers University), The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali IEP

- ↑ Nyaya Realism, in Perceptual Experience and Concepts in Classical Indian Philosophy, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2015)

- ↑ Nyaya: Indian Philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

- ↑ Dale Riepe (1996), Naturalistic Tradition in Indian Thought, ISBN:978-8120812932, pages 227-246

- ↑ Analytical philosophy in early modern India J Ganeri, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ Oliver Leaman (2006), Shruti, in Encyclopaedia of Asian Philosophy, Routledge, ISBN:978-0415862530, page 503

- ↑ Mimamsa Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

- ↑ JN Mohanty (2001), Explorations in Philosophy, Vol 1 (Editor: Bina Gupta), Oxford University Press, page 107-108

- ↑ Oliver Leaman (2000), Eastern Philosophy: Key Readings, Routledge, ISBN:978-0415173582, page 251; R Prasad (2009), A Historical-developmental Study of Classical Indian Philosophy of Morals, Concept Publishing, ISBN:978-8180695957, pages 345-347

- ↑ Reginald Ray (1999), Buddhist Saints in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN:978-0195134834, pages 237-240, 247-249

- ↑ Padmanabh S Jaini (2001), Collected papers on Buddhist Studies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN:978-8120817760, pages 57-77

- ↑ AL Basham (1951), History and Doctrines of the Ajivikas - a Vanished Indian Religion, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN:978-8120812048, pages 94-103

- ↑ "dravya – Jainism". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/topic/dravya.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Jay L. Garfield; William Edelglass (2011). The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 168. ISBN 978-0-19-532899-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=I0iMBtaSlHYC.

- ↑ Brian K. Smith (1998). Reflections on Resemblance, Ritual, and Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 14. ISBN 978-81-208-1532-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=nkruE6UCz54C.

- ↑ Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Routledge. pp. 322–323. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=ienxrTPHzzwC.

- ↑ [a] Anatta, Encyclopædia Britannica (2013), Quote: "Anatta in Buddhism, the doctrine that there is in humans no permanent, underlying soul. The concept of anatta, or anatman, is a departure from the Hindu belief in atman ("the self")."; [b] Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press, ISBN:978-0791422175, page 64; "Central to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the [Buddhist] doctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence."; [c] John C. Plott et al (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Axial Age, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN:978-8120801585, page 63, Quote: "The Buddhist schools reject any Ātman concept. As we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism"; [d] Katie Javanaud (2013), Is The Buddhist 'No-Self' Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana?, Philosophy Now; [e] David Loy (1982), Enlightenment in Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta: Are Nirvana and Moksha the Same?, International Philosophical Quarterly, Volume 23, Issue 1, pages 65-74

- ↑ Jeffrey D Long (2009), Jainism: An Introduction, Macmillan, ISBN:978-1845116255, page 199

- ↑ Basham 1951, pp. 145-146.

- ↑ Basham 1951, Chapter 1.

- ↑ James Lochtefeld, "Ajivika", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing. ISBN:978-0823931798, page 22

- ↑ Ajivikas World Religions Project, University of Cumbria, United Kingdom

- ↑ Johannes Quack (2014), The Oxford Handbook of Atheism (Editors: Stephen Bullivant, Michael Ruse), Oxford University Press, ISBN:978-0199644650, page 654

- ↑ Analayo (2004), Satipaṭṭhāna: The Direct Path to Realization, ISBN:978-1899579549, pages 207-208

- ↑ Basham 1951, pp. 240-261, 270-273.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Cowell and Gough, p. 4

- ↑ Bhattacharya, Ramkrishna. Materialism in India: A Synoptic View. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Chousalkar 1986, pp. 130-134.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Wadia 1956, p. 64-65.

- ↑ Urwick 1920.

- ↑ Keith 2007, pp. 602-603.

- ↑ RC Mishra (2013), Moksha and the Hindu Worldview, Psychology & Developing Societies, Vol. 25, No. 1, pages 21-42; Chousalkar, Ashok (1986), Social and Political Implications of Concepts Of Justice And Dharma, pages 130-134

- ↑ Jalal-e-din Ashtiyani. Zarathushtra, Mazdayasna and Governance.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Whitley, C.F. (Sep 1957). "The Date and Teaching of Zarathustra". Numen 4 (3): 219–223. doi:10.2307/3269345.

- ↑ A. D. Nock (1929), "Studien zum antiken Synkretismus aus Iran und Griechenland by R. Reitzenstein, H. H. Schaeder, Fr. Saxl", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 49 (1), p. 111-116 [111].

- ↑ David N. Livingstone (2002), The Dying God: The Hidden History of Western Civilization, p. 144-145, iUniverse, ISBN:0-595-23199-3.

- ↑ A. D. Nock (1929), "Studien zum antiken Synkretismus aus Iran und Griechenland by R. Reitzenstein, H. H. Schaeder, Fr. Saxl", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 49 (1), p. 111-116.

- ↑ Wherry, Rev. E. M. "A Comprehensive Commentary on the Quran and Preliminary Discourse", 1896. pp 66.

- ↑ Manfred, Albert Zakharovich, ed (1974). A Short History of the World. 1. (translated into English by Katherine Judelson). Moscow: Progress Publishers. p. 182. OCLC 1159025.

Further reading

- Armitage, D., 2007. The declaration of independence: A global history. Harvard University Press.

- Bayly, C.A., 2004. The birth of the modern world, 1780-1914: global connections and comparisons. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hourani, A., 1983. Arabic thought in the liberal age 1798-1939. Cambridge University Press.

- Moyn, S. and Sartori, A. eds., 2013. Global intellectual history. Columbia University Press.

- Watson, P., 2005. Ideas: a history of thought and invention, from fire to Freud (p. 36). New York: HarperCollins.

|