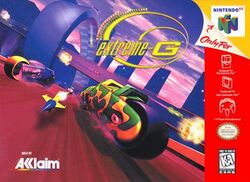

Software:Extreme-G

| Extreme-G | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Probe Entertainment |

| Publisher(s) | Acclaim Entertainment |

| Composer(s) | Simon Robertson |

| Platform(s) | Nintendo 64 |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Racing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

Extreme-G is a futuristic racing video game developed by Probe Entertainment and published by Acclaim Entertainment, featuring an original trance soundtrack. It was released for the Nintendo 64 in 1997, and was released in Japan on May 29, 1998.[2] Despite the crowded field of Nintendo 64 racing games, Extreme-G was met with moderately positive reviews and was a commercial success. A sequel, Extreme-G 2, was released in 1998, followed by two additional games: Extreme-G 3 and XGRA: Extreme G Racing Association.

Gameplay

The gameplay of Extreme-G consists mainly of fast-paced racing through an array of futuristic environments. An array of defensive and offensive weapons are available on-track.[3] These include multi-homing/reverse missiles, magnetic/laser mines, and shield-boosting power-ups. Special weapons can also be found such as invisibility, phosphorus flash and the mighty Wally-Warp which if not avoided, can instantly transport a bike right to the back of the pack.

As with all Extreme-G games, futuristic racing pilots race plasma-powered bikes in an intergalactic Grand Prix at speeds over 750 km/h. The emphasis is on speed and racetrack design, with tracks looping through like roller coasters.

At the beginning of each round, the player is given three "nitro" powerups which provide a temporary speed boost (these powerups cannot be replenished). Also, falling off cliffs or, in some cases, the track itself results in simply losing time rather than losing 'lives'; bikes are teleported back to the track and must rebuild their speed and lost time from a dead standstill.

The single player games come in three difficulty settings: Novice, Intermediate and Extreme. The main game mode (Extreme Contest) features three championships: Atomic (four tracks), Critical Mass (eight tracks) and Meltdown (full 12 standard tracks). The player must come first in each championship to progress. Winning championships on the various difficulty levels will open up the hidden bikes, levels and cheats. Once the levels have been opened they can be used for the additional single and multi-player modes.

The multi-player modes include competitive racing, flag capture, and battle mode.[4]

Plot

Extreme-G is set in the distant future where Earth is reduced into a wasteland. From their new-found planet the human colonists watch their remote controlled bikes wreak havoc through their ancient cities and fight their way to determine which racer manages to qualify.

Development

Extreme-G was developed under the working title "Ultimate Racer".[5] It was created by Probe Entertainment, an internal development team of Acclaim Entertainment.[6]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extreme-G received "favorable" reviews according to the review aggregation website Metacritic.[7] Critics particularly praised the track designs with their numerous loops, jumps, and corkscrews, and the sense of speed.[lower-alpha 1] Crispin Boyer wrote in Electronic Gaming Monthly that no other title delivers sense of speed than Extreme-G.[11] Next Generation said the game has fast, futuristic, heavily armed speedbikes with rollercoaster tracks in some hallucinogenic scenarios.[17] A few critics remarked that the intense speeds give the game a steep learning curve, but that ultimately the controls work well.[20][17] Edge criticized the handling of the bikes, but highlighted the game's emphasis on combat.[10]

The bike designs were also applauded, with several reviewers likening their look to that of the movie Tron.[lower-alpha 2] GameRevolution praised the game's replay value due to the large number of tracks, weapons and multiplayer options.[14] Critics in general complimented the selection of modes and options,[lower-alpha 3] though there were some complaints that the multiplayer modes are not as strong as the single-player. Several noted slowdown and choppiness in the otherwise strong frame rate when four players are racing,[lower-alpha 4] Shawn Smith of Electronic Gaming Monthly said the tracks in the multiplayer Battle mode are dull and unimaginative,[11] and Next Generation simply said that four-player Extreme-G bike deathmatches was a decent idea, but flawed.[17] Most critics remarked that the techno soundtrack is unoriginal but does its job of enhancing the mood of the intense races.[lower-alpha 5] Though many criticized the use of distance fog, reviews unanimously declared the game's graphics to be outstanding.[lower-alpha 6]

Most reviews concluded that while a handful of shortcomings keep Extreme-G from being a top-ranked game, it was impressive enough to recommend. GamePro, for instance, wrote that Extreme G will keep N64 racers sated until F-Zero 64 debuts.[21] Similarly, Peer Schneider of IGN opined that it can't compete with Wave Race 64 and Top Gear Rally in terms of graphics, physics and control, but ultimately recommended it for action and racing fans.[20]

According to N64 Magazine, Extreme-G was a commercial success, selling 700,000 copies by October 1998.[22]

Notes

References

- ↑ "Game Informer News". Game Informer. 1999-01-27. http://www.gameinformer.com/news/oct97/102197b.html. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ↑ "エクストリームG [NINTENDO64"] (in Japanese). Famitsu (Enterbrain). https://www.famitsu.com/cominy/?m=pc&a=page_h_title&title_id=3748&redirect=no. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ↑ "E3 Unleashed!". GamePro (IDG) (106): 38. July 1997.

- ↑ "Extreme-G: Warning: This Game Could Induce Motion Sickness". Electronic Gaming Monthly (Ziff Davis) (100): 42. November 1997.

- ↑ "Gaming Gossip". Electronic Gaming Monthly (Ziff Davis) (93): 28. April 1997.

- ↑ Major Mike (November 1997). "Extreme-G". GamePro (IDG) (110): 92.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Extreme-G for Nintendo 64 Reviews". CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on April 25, 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170425033028/http://www.metacritic.com/game/nintendo-64/extreme-g. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ Marcus C. Fugett. "Extreme-G - Review". All Media Network. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141115195041/http://www.allgame.com/game.php?id=976&tab=review. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ↑ Paul Clancey (January 1998). "Extreme-G". Computer and Video Games (Future Publishing) (194): 68–69.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Extreme-G". Edge (Future Publishing) (53): 107. Christmas 1997. http://www.nintendo64ever.com/scans/mags/Scan-Magazine-572-107.jpg. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 "Review Crew: Extreme-G". Electronic Gaming Monthly (Ziff Davis) (102): 154. January 1998.

- ↑ Andrew Reiner; Andy McNamara; Jon Storm (October 1997). "Extreme-G". Game Informer (FuncoLand) (54): 43. Archived from the original on September 9, 1999. https://web.archive.org/web/19990909145015/http://www.gameinformer.com/cgi-bin/review.cgi?sys=n64&path=oct97&doc=eg. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ↑ Dave "E. Storm" Halverson; David "Chief Hambleton" Hodgson; Guvnor (October 1997). "Extreme G". GameFan (Metropolis Media) 5 (10): 24. https://archive.org/details/Gamefan_Vol_5_Issue_10/page/n29/mode/2up. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Colin (November 1997). "Extreme-G Review". CraveOnline. Archived from the original on January 21, 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/19980121144927/http://www.game-revolution.com/games/n64/extremeg.htm. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Fielder, Joe (October 30, 1997). "Extreme-G Review". CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on November 28, 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20151128102344/https://www.gamespot.com/reviews/extreme-g-review/1900-2544386/. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ Ren Hoek (February 1998). "Extreme G". Hyper (Next Media Pty Ltd) (52): 46–47.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 "Extreme-G". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (37): 142–43. January 1998. https://archive.org/details/NEXT_Generation_37/page/n143/mode/2up. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ↑ Tim Weaver (December 1997). "Extreme G". N64 Magazine (Future Publishing) (9): 48–52.

- ↑ "Extreme-G". Nintendo Power (Nintendo of America) 101: 94. October 1997. http://www.nintendo64ever.com/scans/mags/Scan-Magazine-343-94.jpg. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedIGNr - ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Scary Larry (December 1997). "Nintendo 64 ProReview: Extreme G". GamePro (IDG) (111): 142.

- ↑ "Extreme G2". N64 Magazine (Future Publishing) (20): 10–11. October 1998.

External links

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

|