The Quadrature of the Parabola

The Quadrature of the Parabola (Greek: Τετραγωνισμὸς παραβολῆς) is a treatise on geometry, written by Archimedes in the 3rd century BC. Written as a letter to his friend Dositheus, the work presents 24 propositions regarding parabolas, culminating in a proof that the area of a parabolic segment (the region enclosed by a parabola and a line) is 4/3 that of a certain inscribed triangle.

The statement of the problem used the method of exhaustion. Archimedes may have dissected the area into infinitely many triangles whose areas form a geometric progression. He computes the sum of the resulting geometric series, and proves that this is the area of the parabolic segment. This represents the most sophisticated use of the method of exhaustion in ancient mathematics, and remained unsurpassed until the development of integral calculus in the 17th century, being succeeded by Cavalieri's quadrature formula.

Main theorem

A parabolic segment is the region bounded by a parabola and line. To find the area of a parabolic segment, Archimedes considers a certain inscribed triangle. The base of this triangle is the given chord of the parabola, and the third vertex is the point on the parabola such that the tangent to the parabola at that point is parallel to the chord. By Proposition 1 (Quadrature of the Parabola), a line from the third vertex drawn parallel to the axis divides the chord into equal segments. The main theorem claims that the area of the parabolic segment is 4/3 that of the inscribed triangle.

Structure of the text

Archimedes gives two proofs of the main theorem. The first uses abstract mechanics, with Archimedes arguing that the weight of the segment will balance the weight of the triangle when placed on an appropriate lever. The second, more famous proof uses pure geometry, specifically the method of exhaustion.

Of the twenty-four propositions, the first three are quoted without proof from Euclid's Elements of Conics (a lost work by Euclid on conic sections). Propositions four and five establish elementary properties of the parabola; propositions six through seventeen give the mechanical proof of the main theorem; and propositions eighteen through twenty-four present the geometric proof.

Geometric proof

Dissection of the parabolic segment

The main idea of the proof is the dissection of the parabolic segment into infinitely many triangles, as shown in the figure to the right. Each of these triangles is inscribed in its own parabolic segment in the same way that the blue triangle is inscribed in the large segment.

Areas of the triangles

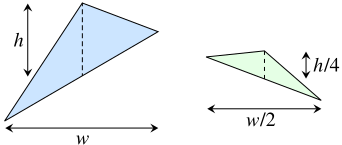

In propositions eighteen through twenty-one, Archimedes proves that the area of each green triangle is one eighth of the area of the blue triangle. From a modern point of view, this is because the green triangle has half the width and a fourth of the height:[1]

By extension, each of the yellow triangles has one eighth the area of a green triangle, each of the red triangles has one eighth the area of a yellow triangle, and so on. Using the method of exhaustion, it follows that the total area of the parabolic segment is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Area}\;=\;T \,+\, 2\left(\frac{T}{8}\right) \,+\, 4\left(\frac{T}{8^2}\right) \,+\, 8 \left(\frac{T}{8^3}\right) \,+\, \cdots. }[/math]

Here T represents the area of the large blue triangle, the second term represents the total area of the two green triangles, the third term represents the total area of the four yellow triangles, and so forth. This simplifies to give

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Area}\;=\;\left(1 \,+\, \frac{1}{4} \,+\, \frac{1}{16} \,+\, \frac{1}{64} \,+\, \cdots\right)T. }[/math]

Sum of the series

To complete the proof, Archimedes shows that

- [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \,+\, \frac{1}{4} \,+\, \frac{1}{16} \,+\, \frac{1}{64} \,+\, \cdots\;=\; \frac{4}{3}. }[/math]

The formula above is a geometric series—each successive term is one fourth of the previous term. In modern mathematics, that formula is a special case of the sum formula for a geometric series.

Archimedes evaluates the sum using an entirely geometric method,[2] illustrated in the adjacent picture. This picture shows a unit square which has been dissected into an infinity of smaller squares. Each successive purple square has one fourth the area of the previous square, with the total purple area being the sum

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{4} \,+\, \frac{1}{16} \,+\, \frac{1}{64} \,+\, \cdots. }[/math]

However, the purple squares are congruent to either set of yellow squares, and so cover 1/3 of the area of the unit square. It follows that the series above sums to 4/3 (since 1+1/3 = 4/3).

See also

- History of calculus

Notes

- ↑ The green triangle has half of the width of blue triangle by construction. The statement about the height follows from the geometric properties of a parabola, and is easy to prove using modern analytic geometry.

- ↑ Strictly speaking, Archimedes evaluates the partial sums of this series, and uses the Archimedean property to argue that the partial sums become arbitrarily close to 4/3. This is logically equivalent to the modern idea of summing an infinite series.

Further reading

- Ajose, Sunday and Roger Nelsen (June 1994). "Proof without Words: Geometric Series". Mathematics Magazine 67 (3): 230. doi:10.2307/2690617.

- Ancora, Luciano (2014). "Quadrature of the parabola with the square pyramidal number". Archimede 66 (3). https://www.zentralblatt-math.org/matheduc/en/?q=an%3A2016f.01058.

- Bressoud, David M. (2006). A Radical Approach to Real Analysis (2nd ed.). Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 0-88385-747-2..

- Dijksterhuis, E.J. (1987) "Archimedes", Princeton U. Press ISBN 0-691-08421-1

- Edwards Jr., C. H. (1994). The Historical Development of the Calculus (3rd ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-387-94313-7..

- Heath, Thomas L. (2011). The Works of Archimedes (2nd ed.). CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-4637-4473-1.

- Simmons, George F. (2007). Calculus Gems. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-561-4. https://archive.org/details/calculusgemsbrie0000simm..

- Stein, Sherman K. (1999). Archimedes: What Did He Do Besides Cry Eureka?. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 0-88385-718-9. https://archive.org/details/archimedeswhatdi00stei.

- Stillwell, John (2004). Mathematics and its History (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-387-95336-1..

- Swain, Gordon and Thomas Dence (April 1998). "Archimedes' Quadrature of the Parabola Revisited". Mathematics Magazine 71 (2): 123–30. doi:10.2307/2691014.

- Wilson, Alistair Macintosh (1995). The Infinite in the Finite. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-853950-9..

External links

- Casselman, Bill. "Archimedes' quadrature of the parabola". https://web.archive.org/web/20120204050048/http://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/archimedes/parabola.html. Full text, as translated by T.L. Heath.

- Xavier University Department of Mathematics and Computer Science. "Archimedes of Syracuse". http://www.cs.xu.edu/math/math147/02f/archimedes/archpartext.html. Text of propositions 1–3 and 20–24, with commentary.

- http://planetmath.org/ArchimedesCalculus