Transversality (mathematics)

In mathematics, transversality is a notion that describes how spaces can intersect; transversality can be seen as the "opposite" of tangency, and plays a role in general position. It formalizes the idea of a generic intersection in differential topology. It is defined by considering the linearizations of the intersecting spaces at the points of intersection.

Definition

Two submanifolds of a given finite-dimensional smooth manifold are said to intersect transversally if at every point of intersection, their separate tangent spaces at that point together generate the tangent space of the ambient manifold at that point.[1] Manifolds that do not intersect are vacuously transverse. If the manifolds are of complementary dimension (i.e., their dimensions add up to the dimension of the ambient space), the condition means that the tangent space to the ambient manifold is the direct sum of the two smaller tangent spaces. If an intersection is transverse, then the intersection will be a submanifold whose codimension is equal to the sums of the codimensions of the two manifolds. In the absence of the transversality condition the intersection may fail to be a submanifold, having some sort of singular point.

In particular, this means that transverse submanifolds of complementary dimension intersect in isolated points (i.e., a 0-manifold). If both submanifolds and the ambient manifold are oriented, their intersection is oriented. When the intersection is zero-dimensional, the orientation is simply a plus or minus for each point.

One notation for the transverse intersection of two submanifolds and of a given manifold is . This notation can be read in two ways: either as “ and intersect transversally” or as an alternative notation for the set-theoretic intersection of and when that intersection is transverse. In this notation, the definition of transversality reads

Transversality of maps

The notion of transversality of a pair of submanifolds is easily extended to transversality of a submanifold and a map to the ambient manifold, or to a pair of maps to the ambient manifold, by asking whether the pushforwards of the tangent spaces along the preimage of points of intersection of the images generate the entire tangent space of the ambient manifold.[2] If the maps are embeddings, this is equivalent to transversality of submanifolds.

Meaning of transversality for different dimensions

Suppose we have transverse maps and where and are manifolds with dimensions and respectively.

The meaning of transversality differs a lot depending on the relative dimensions of and . The relationship between transversality and tangency is clearest when .

We can consider three separate cases:

- When , it is impossible for the image of and 's tangent spaces to span 's tangent space at any point. Thus any intersection between and cannot be transverse. However, non-intersecting manifolds vacuously satisfy the condition, so can be said to intersect transversely.

- When , the image of and 's tangent spaces must sum directly to 's tangent space at any point of intersection. Their intersection thus consists of isolated signed points, i.e. a zero-dimensional manifold.

- When this sum needn't be direct. In fact it cannot be direct if and are immersions at their point of intersection, as happens in the case of embedded submanifolds. If the maps are immersions, the intersection of their images will be a manifold of dimension

Intersection product

Given any two smooth submanifolds, it is possible to perturb either of them by an arbitrarily small amount such that the resulting submanifold intersects transversally with the fixed submanifold. Such perturbations do not affect the homology class of the manifolds or of their intersections. For example, if manifolds of complementary dimension intersect transversally, the signed sum of the number of their intersection points does not change even if we isotope the manifolds to another transverse intersection. (The intersection points can be counted modulo 2, ignoring the signs, to obtain a coarser invariant.) This descends to a bilinear intersection product on homology classes of any dimension, which is Poincaré dual to the cup product on cohomology. Like the cup product, the intersection product is graded-commutative.

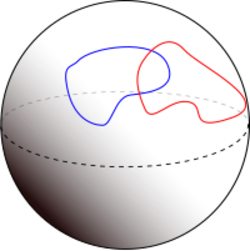

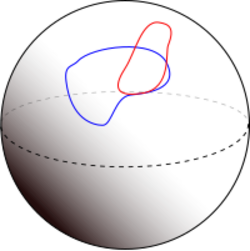

Examples of transverse intersections

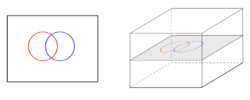

The simplest non-trivial example of transversality is of arcs in a surface. An intersection point between two arcs is transverse if and only if it is not a tangency, i.e., their tangent lines inside the tangent plane to the surface are distinct.

In a three-dimensional space, transverse curves do not intersect. Curves transverse to surfaces intersect in points, and surfaces transverse to each other intersect in curves. Curves that are tangent to a surface at a point (for instance, curves lying on a surface) do not intersect the surface transversally.

Here is a more specialised example: suppose that is a simple Lie group and is its Lie algebra. By the Jacobson–Morozov theorem every nilpotent element can be included into an -triple . The representation theory of tells us that . The space is the tangent space at to the adjoint orbit and so the affine space intersects the orbit of transversally. The space is known as the "Slodowy slice" after Peter Slodowy.

Applications

Optimal control

In fields utilizing the calculus of variations or the related Pontryagin maximum principle, the transversality condition is frequently used to control the types of solutions found in optimization problems. For example, it is a necessary condition for solution curves to problems of the form:

- Minimize where one or both of the endpoints of the curve are not fixed.

In many of these problems, the solution satisfies the condition that the solution curve should cross transversally the nullcline or some other curve describing terminal conditions.

Smoothness of solution spaces

Using Sard's theorem, whose hypothesis is a special case of the transversality of maps, it can be shown that transverse intersections between submanifolds of a space of complementary dimensions or between submanifolds and maps to a space are themselves smooth submanifolds. For instance, if a smooth section of an oriented manifold's tangent bundle—i.e. a vector field—is viewed as a map from the base to the total space, and intersects the zero-section (viewed either as a map or as a submanifold) transversely, then the zero set of the section—i.e. the singularities of the vector field—forms a smooth 0-dimensional submanifold of the base, i.e. a set of signed points. The signs agree with the indices of the vector field, and thus the sum of the signs—i.e. the fundamental class of the zero set—is equal to the Euler characteristic of the manifold. More generally, for a vector bundle over an oriented smooth closed finite-dimensional manifold, the zero set of a section transverse to the zero section will be a submanifold of the base of codimension equal to the rank of the vector bundle, and its homology class will be Poincaré dual to the Euler class of the bundle.

An extremely special case of this is the following: if a differentiable function from reals to the reals has nonzero derivative at a zero of the function, then the zero is simple, i.e. it the graph is transverse to the x-axis at that zero; a zero derivative would mean a horizontal tangent to the curve, which would agree with the tangent space to the x-axis.

For an infinite-dimensional example, the d-bar operator is a section of a certain Banach space bundle over the space of maps from a Riemann surface into an almost-complex manifold. The zero set of this section consists of holomorphic maps. If the d-bar operator can be shown to be transverse to the zero-section, this moduli space will be a smooth manifold. These considerations play a fundamental role in the theory of pseudoholomorphic curves and Gromov–Witten theory. (Note that for this example, the definition of transversality has to be refined in order to deal with Banach spaces!)

Grammar

"Transversal" is a noun; the adjective is "transverse."

quote from J.H.C. Whitehead, 1959[3]

See also

Notes

References

- Thom, René (1954). "Quelques propriétés globales des variétés differentiables". Comment. Math. Helv. 28 (1): 17–86. doi:10.1007/BF02566923.

- Guillemin, Victor; Pollack, Alan (1974). Differential Topology. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-212605-2.

- Hirsch, Morris (1976). Differential Topology. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90148-5.