Verdigris

| Verdigris | |

|---|---|

| Hex triplet | #43B3AE |

| Source | [1] |

| ISCC–NBS descriptor | Brilliant bluish green |

Verdigris /ˈvɜːrdɪɡriː(s)/[1] is a common name for any of a variety of somewhat poisonous[2][3][4][5] copper salts of acetic acid, which range in colour from green to a bluish-green depending on their chemical composition.[6]: 132 Verdigris has been used for artistic purposes from antiquity until the late 20th century, including in easel painting, polychromatic sculptures, and illumination of maps.[7] Verdigris was a common ingredient in colouring agents and pharmaceutical preparations.[7]: 414 Until the 19th century, verdigris was the most vibrant green pigment available and was frequently used in paintings.[8] However, due to its instability, its popularity declined as other green pigments became readily available.[9]: 171 The instability of its appearance stems from its hydration level and basicity, which changes as the pigment interacts with other materials over time.[10]: 637

History

Etymology

| Look up verdigris in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The name verdigris comes from the Middle English vertegrez, from the Old French verte grez. According to one view, it comes from vert d'aigre,[11] "green [made by action] of vinegar". The modern French writing of this word is vert-de-gris ("green of grey"), sounding like the older name verdet gris ("grey greenish"), itself a deformation of verte grez. It was used as a pigment in paintings and other art objects (as green color), mostly imported from Greece, and hence it is more usually given another etymology as vert-de-Grèce ("green of Greece").[12][13]

Industry

The industry was long dominated by the women of Montpelier, France, which had the ideal climate to produce pulverised verdigris.[9]: 177 It was a profitable business, and 80% of production was sold abroad through certified female brokers. At the height of its popularity, in the 1710s, the government had to enforce inspection systems to address growing fraudulent practices. By the 20th century, the production of verdigris had moved away from Montpellier and more cost-efficient methods of producing green pigments sent the industry into decline after WWI.[9]: 179–182

Production

Copper(II) acetate is prepared by treatment of copper(II) hydroxide with acetic acid.[14] The historical methods used for producing verdigris have been recorded in artistic treaties, manuscripts on alchemy, works in natural history, and texts on medicine.[7]: 414 The most common ingredients used were copper and vinegar. Throughout history, recipes changed. In the Middle Ages, copper strips were attached to a wooden block with acetic acid; the block was then buried in dung. A few weeks later, the block was to be dug up, and the verdigris scraped off.[15] Another method of production was developed in 18th-century Montpellier, where it was manufactured in household cellars using copper plates stacked in clay pots that were filled with distilled wine.[14] The acid in the grapes caused the copper to develop crystals. The crystals ripened into verdigris and were scraped off when matured.[9]: 172

Visual characteristics

Verdigris is a collective term for copper acetate, whose chemical varieties produce different hues. The technical literature is inconsistent in describing these variations. Some sources refer to "neutral verdigris" as copper(II) acetate monohydrate (Cu(CH

3CO

2)

2·(H

2O)) and to "blue verdigris" as Cu(CH

3CO

2)

2·CuO·(H

2O)

6.[16] Other sources describe the main copper salt in natural verdigris as Cu

4SO

4(OH)

6 (brochantite).[17] Still other sources describe it as basic copper carbonate (Cu

2CO

3(OH)

2),[18] or as Cu(CH

3CO

2)

2·(Cu(OH)

2)n where n varies from 0 to 3.[19] In marine environments, the main copper salt is tribasic copper chloride (Cu

2(OH)

3Cl).[17][18]

Overall, variations of verdigris can be divided into two groups: basic verdigris and neutral verdigris.[6]: 132 The difference in colour depends on the hydration level and degrees of basicity.[10]: 637

Notable occurrences

Pigment

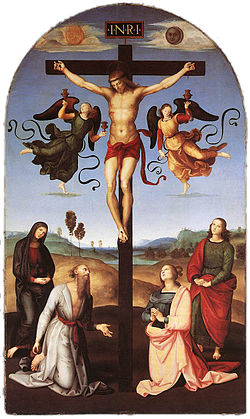

Verdigris has been used as a pigment since antiquity, including in paintings in Rome and Pompeii. The use of verdigris continued into the Middle Ages, Renaissance and Baroque paintings.[6]: 132 It has been identified in The Last Supper (1306) by Giotto.[6]: 142 During the 15th and 16th centuries, it was used in paintings for its transparency and brilliance.[10]: 637 It was difficult to create strong green colors in paintings due to the limitations of the existing green, yellow and blue pigments. In early Italian, Netherlandish, and German paintings, verdigris was widely used to create pure green tones for landscapes and drapery, such as the green coat of Saint John in the Mond Crucifixion by Raphael.[20]: 46 Verdigris was used as both glaze and opaque paint. When verdigris glaze was combined with lead white or lead-tin yellow, it created a deeply saturated green.[6]: 132-136 It was used in oil-based house paint for French and Dutch country houses. Verdigris also was used as an imitation of 'Chinese varnish' on European lacquer.[9]: 175–176 However, during the 19th century, the use of verdigris began to decrease as alternatives such as Emerald Green and viridian became more popular.[6]: 132

Medical uses

Verdigris has also been used in medicine and is identified in the Pharmacologia of John Ayrton Paris as the healing rust of the Spear of Telephus mentioned by Homer.[21][22] Verdigris solids were also used for pharmaceutical preparations in the 18th century to treat canker sores.[9]: 176

Toxicity

Verdigris is poisonous.[2][3][4][5] Symptoms of toxicity include nausea, anemia and death. Some hypothesize people can gain immunity from exposure as happened with female workers in Montpellier. However the toxicity is still severe. As a result its usage has been phased out in favor of nontoxic substitutes.[23]

Permanence

Verdigris is subject to colour change. The changes are most pronounced during the first month of exposure to air. The changes also depend on the type of binding agent and type of verdigris used. For example, changes are less pronounced with neutral verdigris in oil and egg tempera compared to basic verdigris.[6]: 135 With aging, the green pigment in these applications will show signs of browning or darkening.[10]: 637 For example, in Botticelli's The Mystical Nativity, from 1500, the blue-green costumes of the angels have darkened to a dark green colour.[24]

Verdigris is lightfast in oil paint, as numerous examples of 15th-century paintings show. However, its lightfastness and air resistance are very low in other media. Copper resinate, made from verdigris by boiling it in a resin, is not lightfast, even in oil paint. In the presence of light and air, green copper resinate becomes stable brown copper oxide.[12] The browning mechanism is attributed to the transient formation of Cu(I) in the pigment and oil system. The reduction of Cu(II) into Cu(I) due to the release of a carboxylate, causes changes in the optical properties of pigment. Furthermore, linseed oil induces the transformation of the copper acetate bimetallic structure, and forms monomeric series. Dioxygen that reacts with partially decarboxylated dimers to form a peroxy-Cu dimer complex is responsible for the darkening of the pigment.[10]: 635–638

In previous literature on painting, verdigris has been described as unstable when combined with other pigments which leads to further deterioration. Due to the fickle nature of the pigment, it required special preparation of paint, carefully layered application, and immediate sealing with varnish to avoid rapid discoloration (but not in the case of oil paint).[12] However, further scientific research suggests that the difficulties are less extreme than previously described. The pigment nonetheless has the ability to degrade cellulosic materials, such as paper.[6]: 137 In terms of identification and reproduction, modern technology and reproducible synthesis procedures have been developed to be used for museums and collections to identify distinct verdigris phases in historical artworks.[20]: 14857 Certain components of historical verdigris pigments, copper(II) acetates, are partially irreproducible based on the given historical recipes.[20]: 14847

See also

- Bronze disease

- Green pigments

- List of colors

- List of inorganic pigments

- Patina

References

- ↑ "Its pronunciation in English is still unsettled" (Fowler's Dictionary of Modern English Usage (4 ed.) edited by: Jeremy Butterfield). The pronunciation /-ɡriːs/ is the first one given by Merriam-Webster's dictionary, but /-ɡriː/ is first in the Oxford Dictionary of English (3 ed.) (2015).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Verdigris". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Verdigris.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Karmakar, Rabindra N. (2015). Forensic medicine and toxicology: theory, oral & practical. Academic Publishers.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Anant, Jagdish Kumar, S. R. Inchulkar, and Sangeeta Bhagat (2018). "An overview of copper toxicity relevance to public health." EJPMR 5, no. 11 : 236.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Poisoning by Verdigris". The Lancet 39 (1013): 663–664. January 1843. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)76992-4. ISSN 0140-6736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)76992-4.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 H. Kühn, Verdigris and Copper Resinate, in Artists' Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2: A. Roy (Ed.) Oxford University Press 1993, p. 131 – 158

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 De la Roja, José Manuel; San Andrés, Margarita; Cubino, Natalia Sancho; Santos-Gómez, Sonia (2007). "Variations in the colorimetric characteristics of verdigris pictorial films depending on the process used to produce the pigment and the type of binding agent used in applying it". Color Research & Application 32 (5): 414–423. doi:10.1002/col.20311. ISSN 0361-2317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/col.20311.

- ↑ Verdigris, ColourLex

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Benhamou, Reed (1984). "Verdigris and the Entrepreneuse". Technology and Culture 25 (2): 171–181. doi:10.2307/3104711. ISSN 0040-165X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3104711.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Santoro, Carlotta; Zarkout, Karim; Le Hô, Anne-Solenn; Mirambet, François; Gourier, Didier; Binet, Laurent; Pagès-Camagna, Sandrine; Reguer, Solenn et al. (2014-01-29). "New highlights on degradation process of verdigris from easel paintings". Applied Physics A 114 (3): 637–645. doi:10.1007/s00339-014-8253-2. ISSN 0947-8396. Bibcode: 2014ApPhA.114..637S. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00339-014-8253-2.

- ↑ Dauthenay, Henri (1905). Répertoire de couleurs pour aider à la détermination des couleurs des fleurs, des feuillages et des fruits. 2. Paris: Librairie horticole. p. 240. RC2. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k64453604/f94.image.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 215. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- ↑ The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, edited by T. F. Hoad (1996), and Merriam-Webster's dictionary give only this second etymology.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Solomon, Sally D.; Rutkowsky, Susan A.; Mahon, Megan L.; Halpern, Erica M. (2011). "Synthesis of Copper Pigments, Malachite and Verdigris: Making Tempera Paint". Journal of Chemical Education 88 (12): 1694–1697. doi:10.1021/ed200096e. Bibcode: 2011JChEd..88.1694S.

- ↑ Darnton, Robert. "A Bourgeois Puts His World in Order" in The Great Cat Massacre --and other Episodes in French Cultural History. New York: Vintage Books, 1985. p. 114.

- ↑ Richardson, H. Wayne (2000). "Copper Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_567. ISBN 3527306730.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Fitzgerald, K.P.; Nairn, J.; Atrens, A. (1998). "The chemistry of copper patination". Corrosion Science 40 (12): 2029–2050. doi:10.1016/s0010-938x(98)00093-6. ISSN 0010-938X.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Sharp, D. W. A: Penguin Dictionary of Chemistry, page 419. Penguin Books, 1990 (2nd edition)

- ↑ Kühn, Hermann (1970). "Verdigris and Copper Resinate". Studies in Conservation 15: 12–36. doi:10.1179/sic.1970.15.1.002.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Bette, Sebastian; Kremer, Reinhard K.; Eggert, Gerhard; Tang, Chiu C.; Dinnebier, Robert E. (2017). "On verdigris, part I: synthesis, crystal structure solution and characterisation of the 1–2–0 phase (Cu3(CH3COO)2(OH)4)". Dalton Transactions 46 (43): 14847–14858. doi:10.1039/c7dt03288a. ISSN 1477-9226. PMID 29043336.

- ↑ "Medical Uses of Copper in Antiquity". http://www.copper.org/publications/newsletters/innovations/2000/06/medicine-chest.html.

- ↑ Paris, John Ayrton (1831). Pharmacologia. New York: W. E. Dean. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/62958. "The rust of the spear of Telephus, mentioned in Homer as a cure for the wounds which that weapon inflicted, was probably Verdegris, and led to the discovery of its use as a surgical application"

- ↑ "What's The Deal With Verdigris?" (in en). https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/whats-the-deal-with-verdigris-a-brief-history-of-a-very-old-color-199569.

- ↑ Bomford, David; Ashok, Roy (2009). A Closer Look at Colour. London: National Gallery, London. pp. 38. ISBN 978-1-85709-442-8.

External links

- National Pollutant Inventory – Copper and compounds fact sheet

- Verdigris, ColourLex

- Making Pigments – Verdigris, Paul Grosse

|