Vert (heraldry)

| Vert | |

|---|---|

| Class | Colour |

| Non-heraldic equivalent | Green |

| Monochromatic designations | |

| Hatching pattern | |

| Tricking abbr. | v., vt. |

| Poetic designations | |

| Heavenly body | Venus |

| Jewel | Emerald |

| Virtue | Love |

In British heraldry, vert (/vɜːrt/) is the tincture equivalent to green. It is one of the five dark tinctures called colours.

Vert is commonly found in modern flags and coat of arms, and to a lesser extent also in the classical heraldry of the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period.

Green flags were historically carried by Ottokar II of Bohemia in the 13th century. In the modern period, a green ensign was flown by Irish vessels, becoming a symbol of Irish nationalism in the 19th and 20th century. The Empire of Brazil used a yellow rhombus on a green field from 1822, now seen in the flag of Brazil. In the 20th century, a green field was chosen for a number of national flag designs, especially in the Arab and Muslim world because of the symbolism of green in Islam, including the solid green flag of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977).

Vert is portrayed in heraldic hatching by lines at a 45-degree angle from upper left to lower right, or indicated by the abbreviation v. or vt. when a coat of arms is tricked.

Etymology

Vert is simply the French word for "green". It has been used in English in the sense of a heraldic tincture since the early 16th century.

Vert is not used in modern French heraldry. Instead, sinople has been used for green since at least the 16th century. Earlier in the medieval period, however, vert was used for green while sinople originally referred to a shade of red before becoming associated with green.

In Spanish heraldry, either sinople or verde can be used for green. Verde is also used in Portugal. In both the Spanish and Portuguese languages, verde literally translates as "green". In German heraldry, they use grün, which also translates as "green".

Middle Ages

The green tincture was left out of some heraldic works in the Middle Ages, but the first known English treatise, the Anglo-Norman "De Heraudie" (dated to sometime between 1230 and 1345), lists vert among the other tinctures.[1]

The French term sinople was in use prior to the 15th century, but it did not refer to green, but rather to red, being identical in origin to Cinnabar, originally the name of a red pigment also known as sinopia. Descriptions of knightly shields as painted at least partly green in Arthurian romance are found earlier, even in the late 12th century.[2] Here, the Chevalier au Vert Escu ("knight with the green shield") often marks a kind of supernatural character outside of normal chivalric society (as is still the case with the English "Green Knight" of c. 1390), perhaps[clarification needed] in connection with the Wild Man or Green Man of medieval figurative art. The Anglo-Norman prose Brut (c. 1200) has Brutus of Troy bear a green shield, Brutus Vert-Escu, Brutus Viride Scutum.

Green is occasionally found in historical coats of arms (as opposed to the fictional "green knights" of Arthurian romance) from as early as the 13th century, but it remained rare, and indeed actively avoided, well into the 15th century, but becomes more common in the classical heraldry of the 16th and 17th centuries.[3]

According to Paweł Dudziński, the chairman of the Heraldic Committee within the Polish Ministry of Interior and Administration, early heraldic green used to be bright, obtained from verdigris pigment, which allowed contrast with azure (obtained from dark ultramarine pigment) in arms that contravened the rule of tincture.[4]

An early example of a green escutcheon was that of the coat of arms of Styria,[year needed] based on the banner of Ottokar II of Bohemia (r. 1253–1278), described by chronist Ottokar aus der Gaal (c. 1315) as:

- ein banier grüene als ein gras / darin ein pantel swebte / blanc, als ob ez lebte

- "a banner green as grass, therein suspended a panther in white, [depicted] as if alive."

A curious example occurs in an early armorial of the Burgundian Order of the Knights of the Golden Fleece (Toison d'Or) where the arms of the Lannoy family are recorded as "argent, three lions rampant sinople, etc." Despite the fact that sinople signified a shade of red in early heraldry, the lions in this 15th century manuscript are clearly green, although rather faded. The fugitive nature of the green pigments of that day may have had some influence on the low use of that colour in early heraldry.

Classical heraldry

During the 16th century, green was still rare as a tincture for the field of a coat of arms, but it was used increasingly for the heraldic designs shown in the field, especially when depicting trees or other vegetation. Thus, the coat of arms of Hungary shows a "double cross on a hill" as a symbol of the Árpád kings, where the cross was shown in silver (argent) and the hill in green, from the late 14th century.[5]

The only green shown in the arms of the states of the Holy Roman Empire in the Quaternion Eagle by Hans Burgkmair (c. 1510) are the crancelin of Saxony and the Zirbelnuss of Augsburg. The three lions rampant, verts of the Marquessate of Franchimont are attested in the 16th century.

Siebmachers Wappenbuch of 1605 shows a number of green heraldic devices in the coat of arms of cities. For example, the coat of arms of the town of Waldkappel ("forest chapel") as depicting a chapel in a forest on a red field, with the ground on which the chapel is standing, and four trees behind the chapel, drawn in green. There are a number of other examples where Siebmacher as a green "mount" (the heraldic "hill" at the bottom of the shield on which the heraldic charge is "standing"). For the town of Grünberg, Siebmacher shows a yellow field on which a knight is riding, his horse running on a green "hill" and the knight flying a green banner.[6]

Poetic meanings

The different tinctures are traditionally associated with particular heavenly bodies, precious stones, virtues, and flowers, although these associations have been mostly disregarded by serious heraldists.[7] Vert is associated with:

Gallery

-

Coat of arms Hrabišín municipality, Šumperk District, Czechia

-

Coat of arms of Grüningen (Zürich, Switzerland)

-

Shield of the province of Ontario, Canada

-

Coat of Arms of Listringen, Germany

-

Coat of arms of Zabakuck, Germany

Modern flags

Historically, a Green Ensign was flown by Irish merchant vessels from the late 17th century. Green flags flown by revolutionary uprisings include the one used in the Vaudois insurrection against Bernese rule in the 1790s (which became the basis of the modern coat of arms of Vaud), the flag of the Irish Saint Patrick's Battalion (1846–1848), and the flag of the Easter Rising (1916).

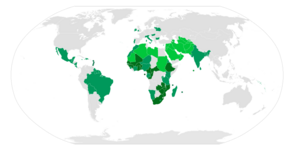

In the 20th century, a number of national flags were designed involving green, especially in the Muslim world, based on the traditional symbolism of green in Islam, and as one of the Pan-Arab colours. Green is also common among the national flags of African countries: Green is one of the Pan-African colours. Other countries have used the colour green in their flags to represent the "greenness" of their lands and abundance of their nation.

The following contemporary national flags feature a solid-green field:

- the Flag of Brazil (1889, Empire of Brazil from 1822): a yellow rhombus on a green field, in the rhombus a blue disc depicting a starry sky spanned by a curved band inscribed with the national motto,

- the flag of Pakistan (1947): a white star and crescent on a dark green field, with a vertical white stripe at the hoist,

- the flag of Mauritania (1959): green, with a golden upward-pointed crescent and star,

- the flag of Zambia (1964): green, at the fly end stripes in red, black and orange and a depiction of an eagle,

- the flag of Bangladesh (1972): a red disc on a green field

- the flag of Saudi Arabia (1973): green, with the shahada inscription and a sword in white.

- the flag of Dominica (1978): green, a cross in yellow, black and white, and a red disc with a depiction of the sisserou parrot,

- the Flag of Turkmenistan (2001): green, with a vertical red stripe near the hoist side, a white waxing crescent moon and five white five-pointed stars appear in the upper corner of the field just to the fly side of the red stripe.

Former national flags with green fields further include the solid-green flag of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977–2011).

References

- ↑ Woodcock, Thomas; Robinson, John Martin (1988). The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-19-211658-4.

- ↑ Le Chevalier de la charrette (c. 1170s) mentions an escu vert d'une part "a partly green shield" (v. 5785). Cligès (c. 1176) mentions a case of armes verts "green arms" (v. 4669). See Brault (1997:286f.)

- ↑ "There was an antipathy towards green until well into the 15th century" Terence Wise, Richard Hook, William Walker Medieval heraldry, vol. 99 of the Men-at-arms series, Osprey Publishing, 1980, ISBN 978-0-85045-348-5, p. 11

- ↑ Dudziński, Paweł. "Rozmowy o heraldyce #1: Paweł Dudziński" (Interview). Interviewed by Artur Wójcik. Sigillum Authenticum.

- ↑ the double cross was used from the 12th century, but the "hill" was added by Louis I of Hungary (r. 1342-1382), later expanded to "three hills" ("on a mount vert a crown Or, issuant therefrom a double cross argent").

- ↑ ed. Appuhn (1989), p. 224.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Woodcock, Thomas; Robinson, John Martin (1988). The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-19-211658-4.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Elvin, Charles Norton (1889). A Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Kent. p. 129. https://archive.org/details/cu31924029796426.

- Brault, Gerard J. (1997). Early Blazon: Heraldic Terminology in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, (2nd ed.). Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-711-4.

External links

|