Biology:Cittarium pica

| Cittarium pica | |

|---|---|

| |

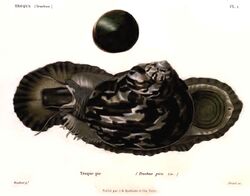

| A colored illustration of a live Cittarium pica, showing the inner surface of the operculum at the top | |

| |

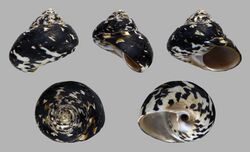

| Five views of a shell of Cittarium pica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Vetigastropoda |

| Order: | Trochida |

| Superfamily: | Trochoidea |

| Family: | Tegulidae |

| Genus: | Cittarium |

| Species: | C. pica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cittarium pica | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

Cittarium pica, common name the West Indian top shell or magpie shell, is a species of large edible sea snail, a marine gastropod mollusk in the family Tegulidae. This species has a large black and white shell.

This snail is known as "wilk" or "wilks" (or sometimes as "whelks") in the English-speaking Caribbean islands of the West Indies, where this is a popular food item. The word "will" or "wilks" can be used both as a singular form and a plural. This species is however not at all closely related to the species that are known as whelks in the U.S. and in Europe. In some Spanish-speaking parts of the Caribbean, when used as a food source Cittarium pica is known as bulgao, or simply as caracoles (snails, in Spanish). In Venezuela it is called quigua;[3] in Cuba it is called cigua.

Cittarium pica is considered the third most economically important invertebrate species in the Caribbean, after the spiny lobster (Panulirus argus) and the queen conch (Eustrombus gigas). It has gone locally extinct in some habitats due to overfishing and overexploitation.[4][5][6]

Taxonomy

Cittarium pica is within the clade Vetigastropoda. The vetigastropods are considered to be among the most primitive living neo-gastropods,[7] and are widely distributed in all oceans of the world. It is also part of the superfamily Trochoidea, presenting nacre as the inner shell layer, and its subordinated family Tegulidae. Woodring et al. (1924) recombined this species as Cittarium picum. Weisbord (1962) recombined it as Livona pica, and it was finally recombined as Cittarium pica by Philippi (1847), Rosenberg (2005) and Hendy et al. (2008).[1]

This is the only living species in the genus Cittarium. For a long time, only one species in the genus Cittarium was known, however in 2002 a fossil species Cittarium maestratii Lozouet, 2002 was discovered in the Oligocene deposits of southwestern France and named.[8][7]

Shell description

The shell of this species can be up to 137 mm in maximum dimension.[7][9] It is very thick and heavy, having an outline that is between trochiform and turbiniform in shape, with rounded shoulders[5] and a somewhat low conical form.[7]

The spire is conoidal. It contains about six convex whorls. The large body whorl is depressed-globose. The outer lip is simple. The lip is edged inside by black, or black and white. The columella is arcuate, produced above in a heavy porcellanous callous deposit, half-surrounding the umbilicus and deeply notched in the middle.

The shell of Cittarium pica presents a rather wide umbilicus, which is deep[5] and devoid of sculpture,[7] but spirally bicostate inside. The semicircular, oblique aperture is distinguishably nacreous inside[5][7] as is the case in other Trochoidea, and is circular. The parietal callus is glossy and delicate, and has a node that projects towards the umbilicus.[7] Juvenile individuals possess shells ornamented by spiral lines and strong cords, in contrast to the nearly smooth, homogeneous surface of mature specimens.[7]

The lusterless color pattern is rather distinct, overall white with black zigzag flammules on each whorl. Those spots have a tendency to become axial lines in older, larger individuals.[7] The upper surface is often entirely black. The aperture is commonly white, with an inner iridescence because of the nacre.

Young shells, or well-preserved adults, have the spire whorls sculptured by oblique folds, cut by a few spiral sulci. The periphery and the base in the half-grown shells are spirally lirate.[10]

- Unusual erosion

On some old, empty shells of large individuals, the black colored parts become slightly higher in relief, compared to the white areas surrounding it. This unusual morphology may be due to the action of blue-green algae, such as Plectonema terebrans, which continuously erode the surface of the white parts of the shell.[7]

Distribution

This species occurs rarely in the Florida Keys, and in the Caribbean coast of Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia and Venezuela. It also occurs in the Bahamas, Cuba, the Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and the Lesser Antilles as far south as Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago. The species has been reintroduced to Bermuda.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

This large snail is found on or under rocks, in exposed and moderately sheltered shores, both in intertidal and shallow subtidal zones.[7] Cittarium pica generally does not live at great depths, though this has occasionally been reported. Most individuals are found at the water's edge,[3][7] and have little tendency to disperse.[3][7] Minimum recorded depth is 0 m.[9] Maximum recorded depth is 7 m.[9]

Life cycle

Cittarium pica is dioecious, which means each individual organism belonging to this species is distinctly male or female.[7] The fertilisation in this species occurs externally.[7] During the reproductive season, which normally occurs from June to November in the field,[7] male individuals release their sperm into the water, as females simultaneously release their green colored unfertilised eggs. The encounter of those gametes produce yolky fertilised eggs, which will further develop into lecitotrophic (yolk feeding) larvae. They emerge from the egg capsules as shell-cap-bearing trochophores. These trochophore larvae do not spend much time in the plankton, because settlement occurs relatively soon, after 3.5 to 4.5 days.[7] Individuals usually reach sexual maturity at shell lengths of 32–34 mm.[7] The life span of this species is still unknown, but estimates for other top shells reach 30 years.[7]

Feeding habits

The west Indian top shell is known to be an herbivore, feeding on a large variety of algae, and sometimes also on detritus. They actively scrape the algal growths off rocks, and this tends to cause erosion over time.[7] Feeding commonly occurs during the nocturnal period, when the snails are most active.[7]

Biological interactions

A small limpet, Lottia leucopleura, often lives on the underside of the shell of this large sea snail.[3] The crab Pinnotheres barbatus is mentioned as a commensal.[7] The sessile vermetid gastropod Dendropoma corrodens (also known as ringed wormsnail) and the tube dwelling polychaete Spirorbis may live attached to the shell of Cittarium pica, as is also the case for several species of algae.[7]

In the wild, the shell of this species is used extensively by the large land hermit crab species Coenobita clypeatus.[3]

Human use

These large sea snails are boiled and eaten in a variety of different local recipes. Because of their popularity as a food item and the problem of overfishing, in the US Virgin Islands there are territorial regulations to protect these snails: no collecting is allowed during their reproductive season, and there is a minimum harvest size regulation.[3]

For a similar reason, Cittarium pica became locally extinct in Bermuda. This caused a serious impact on the land hermit crab populations, because these arthropods need empty Cittarium pica shells (or some other similarly large shell) to use as shelter. Nowadays, Cittarium pica is a legally protected species in Bermuda, where its collection is forbidden.[11]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "The Paleobiology Database". Cittarium pica Linnaeus, 1758 (Top Snail). http://paleodb.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl?action=basicTaxonInfo&taxon_no=90935. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Malacolog (Version 4.1.1)". http://www.malacolog.org/search.php?nameid=637. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Toller, W. (2003). "U.S.V.I. Animal Fact Sheet #15 Whelk". Department of Planning and Natural Resources Division of Fish and Wildlife. http://fw.dpnr.gov.vi/education/FactSheets/PDF_Docs/15Whelk.pdf. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- ↑ Cervigón, F. (1993). "Gastropods". in Carpenter, K.E.. Field guide to the commercial marine and brackish-water resources of the northern coast of South America. FAO species identification sheets for fishery purposes. Rome: FAO. pp. 513. ISBN 92-5-103129-0. http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/t0544e/t0544e00.htm.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Leal, J.H. (2002). Gastropods. p. 99-147. In: Carpenter, K.E. (ed.).The living marine resources of the Western Central Atlantic. Volume 1: Introduction, molluscs, crustaceans, hagfishes, sharks, batoid fishes, and chimaeras. FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes and American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Special Publication No. 5. 1600p.

- ↑ Sartwell, T.. "Marine Invertebrates of Bermuda". in Wood, J. B.; Valdivia, A.. West Indian Top Shell (Cittarium pica). BBSR. http://www.thecephalopodpage.org/MarineInvertebrateZoology/Cittariumpica.html. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 Robertson, R. (2003). "The edible West Indian "whelk" Cittarium pica (Gastropoda: Trochidae): Natural history with new observations". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia) 153 (1): 27–47. doi:10.1635/0097-3157(2003)153[0027:TEWIWC2.0.CO;2]. http://direct.bl.uk/bld/PlaceOrder.do?UIN=144235586&ETOC=RN&from=searchengine. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ↑ Lozouet, P. (2002). "First Record of The Caribbean Genus Cittarium (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Trochidae) From The Oligocene of Europe and its Paleobiogeographic Implications". Journal of Paleontology (Paleontological Society) 76 (4): 767–770. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2002)076<0767:frotcg>2.0.co;2. http://jpaleontol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/extract/76/4/767.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Welch, J. J. (2010). "The "Island Rule" and Deep-Sea Gastropods: Re-Examining the Evidence". PLoS ONE 5 (1): e8776. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008776. PMID 20098740.

- ↑ Tryon (1889), Manual of Conchology XI, Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia

- ↑ Ministry of Environment and Sports: Department of Conservation Services. "Bermuda Species". West Indian Topshell (Cittarium pica). Government of Bermuda. http://www.conservation.bm/west-indian-topshell/. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

Further reading

- Díaz-Ferguson, E.; Haney, R.; Wares, J.; Silliman, B. (2010). "Population Genetics of a Trochid Gastropod Broadens Picture of Caribbean Sea Connectivity". PLoS ONE 5 (9): e12675. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012675. PMID 20844767.

External links

- "Cittarium pica" (in en). Gastropods.com. http://www.gastropods.com/4/Shell_24.shtml.

- Photo of live animal and a lot of information

- More information and recipes from the Cayman Islands

Wikidata ☰ Q3171877 entry

|