History:Paleolithic Iberia

This article may require copy editing for inconsistent tense, general English usage. (April 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Paleolithic in the Iberian peninsula is the longest period of its prehistory, starting c. 1.3 million of years (Ma) ago and ending almost at the same time as Pleistocene, first epoch of Quaternary, c. 11.500 years or 11.5 ka ago. It was a period characterized by climate oscillations between ice ages and small interglacials, producing heavy changes in Iberia's orography.[1] Cultural change within the period is usually described in terms of lithic industry evolution, as described by Grahame Clark.[2]

Multiple archaeological sites containing remains from this period are scattered throughout the peninsula. Of notable importance is Atapuerca (Burgos) containing human fossils spanning the whole period and declared world heritage site by UNESCO in 2000.[3]

Lower Paleolithic

Just as Paleolithic is the longest period of Iberia prehistory, lower Paleolithic (c. 1.3 Ma – 128 ka ago) is the longest part of Paleolithic. It is mainly studied from Homo fossils and lithic tools found at archaeological sites, and spans most of Calabrian (c. 1.8 Ma – 770 ka ago) and Chibanian (c. 770 – 126 ka ago). Calabrian in the peninsula is characterized by a warmer weather and fauna similar to current African savanna, with elephants, cave lions, hyenas, etc. By contrast, Chibanian hosts a number of ice ages, changing typical fauna to big-sized mammals such as cave bears and woolly mammoths.[4]

Iberia was mostly populated by Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis during this period. The two main hypothesis for their arrival to Iberia are either from Africa, crossing through Gibraltar, or from Europe, through the Pyrenees.[5] Homo antecessor would be the last common ancestor of our species, Homo sapiens, and Homo heidelbergensis, who would have evolved into Homo neanderthalensis.[6] There is some imbalance among archaeological discoveries which may suggest two long periods of depopulation of the peninsula (between c. 1.2 Ma and 800 ka ago, and between c. 800 and 600 ka ago), unless new evidence suggests otherwise.[1]

Oldowan

Archaic lower Paleolithic (c. 1.3 Ma – 550 ka ago) corresponds to Oldowan or Mode 1 stone tools, usually called choppers.[1] Both Homo fossils and lithic instruments have been found in Iberia dating from this period. Regarding the former, the most ancient are a partial mandible of an unidentified Homo (c. 1.2 Ma ago) and a maxilla still pending identification (c. 1.4 Ma ago), both discovered in Sima del Elefante, Atapuerca.[4][7]

Atapuerca also hosts several lithic tools from this period, mainly from flint, quartzite, sandsone, quartz and limestone, with flint presenting two variations, one of Neogene origins and other from the Cretaceous, and the rest of materials transported from the fluvial terraces of Arlanzón and Vena, distancing 1 kilometer from the site.[8] The oldest lithic tool remains (c. 1.2 Ma ago) are simple lithic cores and flakes, mainly out of flint, from TE9 at Sima del Elefante. Level TD6 of Gran Dolina (c. 850 ka ago) features lithic tools of more varied materials and functionalities, such as denticulate tools and scrapers, and one limestone chopper.[8]

Level TD6 of Gran Dolina also contains several fossils of Homo antecessor, dated c. 850 ka ago, corresponding to around 11 infant and adolescent individuals, between 4 and 16 years old approximately.[9] They present similar stone tool marks to those of animal fossils, for extracting the spinal cord, thus constituting the first evidence of cannibalism among Homo genus.[6] Another significant archeological site for this period is Guadix-Baza (Andalusia), with Mode 1 stone tools, Calabrian fauna with evidence of manipulation and a human molar dated c.1.4 Ma ago.[1]

Acheulean

During classical lower Paleolithic (c. 550 – 128 ka ago), stone tool manufacturing techniques evolve to Mode 2 or Acheulean, of which the best representative is the biface. This technological mode is first found in Iberia at Barranc de la Boella (Catalonia), with an antiquity of c. 0.9 Ma ago and mostly consisting on choppers and rough bifaces, which is why sometimes these lithic tools are said to be archaic Acheulean, in contrast with those at Galería in Atapuerca.[8] Here, there was an advantageous natural trap used to obtain food, so it was used not for habitation, but to process herbivores that had fallen through it, so they consist mainly of bifaces and cleavers.[10]

Also in Atapuerca, at Sima de los Huesos, archaeologists have found several Homo fossils dated c. 430 ka ago, estimated to correspond to 30 individuals and which have been classified as Homo heidelbergensis.[6] Among them, one of the most well preserved is Miguelón or Skull 5. The site also contains thousands of bones from Ursus deningeri, ancestor of the cavern bear, among others from smaller carnivores. Neither evidence of habitation nor of a catastrophic event has been found at the site, so it has been hypothesized that the pit constitutes the first deliberate burial of bodies among Homo.[6] Mitochondrial DNA retrieved from these individuals, thanks to propitious temperature and humidity preservation conditions at the site, shows astonishing similarities to that of the enigmatic Asian Denisovans, and thus requires further research.[6] Nuclear DNA, by contrast, is more similar to that of the future Homo neanderthalensis, which suggest continuous hybridization processes among the different Homo species.[9]

Homo heidelbergensis is also found at the archaeological site of Cave of Aroeira (Santarém), dated c. 400 ka ago, constituting its most occidental remains in Europe and together with fire remnants.[1][5] The latter was also found at Torralba and Ambrona (Soria), together with lithic tools and many elephant (among other animals) fossils, with and without human manipulation.

Middle Paleolithic

Middle Paleolithic (c. 128 ka – 40 ka ago) is dominated by an extended occupation of Iberia by Homo neanderthalensis or, more popularly, Neanderthal, who had a heavier body, higher lung volume and a bigger brain than Homo sapiens. Important archaeological sites containing Neanderthal fossils are Sidrón Cave (Asturias), Pinilla del Valle (Madrid) and Sima de las Palomas (Murcia).[5] Gorham's cave (Gibraltar) contains Neanderthal rock art, suggesting they had higher symbolic thought abilities than it was previously supposed. This period, as the previous one, is mainly studied from fossils and stone tools.

Mousterian

Mode 3 or Mousterian lithic tools comprehends five different techniques: levallois, discoid, Quina, laminar and bifacial, the first three being the more frequent in Iberia. By contrast with lower Paleolithic, when habitational places were usually in open air and caves were used circumstantially (burial, tool fabrication, butchering), throughout this period caves are increasingly used for habitation, with remains of home conditioning such as archaic cobblestones (Cave of Els Ermitons) or stub walls (Cave of Morín).[1] There is no extended usage of bone or antlers for tool fabrication, and very few wood usage evidence remains because of decomposition.

Further heterogeneity among sites also starts appearing: some evidence long periods of occupation by several generations, for example, Cova Negra (Valencia); others are hunting facilities for animal butchering, similarly to lower Paleolithic; others are primitive lithic workshops, for stone tool manufacturing, such as Cantera Vieja (Madrid); and, finally, others mainly serve for seasonal logistics, taking into account animal migrations, such as Cova Gran (Lleida).

Mousterian archaeological sites can also be found at the end of lower Paleolithic, between 350 ka and 128 ka ago; however, they are scarcer, concentrated over the coast and nonexistent for most part of the southwestern quadrant. Note that, although some of them are nowadays next to the sea, during glacial marine regressions they served as decent lookouts for, then, kilometer long marshes.[1] Mousterian fossils are also found at Atapuerca, in Cueva Fantasma (c. 60 ka ago) and Galería de las Estatuas (c. 110 – 80 ka ago), although they are recent findings and require further research.[9]

Châtelperronian

The Châtelperronian culture, mostly found in southern France , is contemporaneous to the period of time when both Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens coexisted in Europe, and thus at first it was attributed to the latter, but the discovery of a full skeleton from the former changed its attribution to Homo neanderthalensis.[11] Some academics prefer to call it late Mousterian, and there is a debate on whether to consider it either a proper or a transitional industry, since chronologically it belongs to middle Paleolithic but it shows characteristics of upper Paleolithic industries.[11]

This culture extended into northern Iberia, although it is not as well represented. Escoural Cave (Évora) contains evidence of human activity c. 47 ka ago.[12] A Neanderthal skull was found in Forbes' Quarry in Gibraltar in 1848, making it the second territory after Belgium where remains of Neanderthals were found. Subsequent Neanderthal discoveries in Gibraltar have also been made (Devil's Tower Cave).[13] Evidence of their presence in this period is found in Columbeira, Figueira Brava and Salemas.[14] The Cave of Salemas and the Cave of Pego do Diabo, both located in Loures Municipality, were inhabited in the Paleolithic.[15]

Upper Paleolithic

First remains of Homo sapiens appear during upper Paleolithic (c. 40 ka – 11.5 ka ago), around 35 ka ago. For a short time, around 5 ka, both species coexisted, until Homo neanderthalensis remains stop appearing.[5] Some have suggested that the newer remains in Iberia suggest Neanderthals were driven out of Central Europe by modern man to the Iberian peninsula where they sought refuge. Archaeological industries of the Middle Paleolithic in Iberia lasted until about 28 ka or 26 ka BC. In Zafarraya (Andalusia) a Neanderthal mandible (30 ka BP) and Mousterian tools (27 ka BP) were found. Châtelperronian culture is found in Cantabria and in Catalonia. The succession of Homo sapiens cultures during this period are as follows: Aurignacian (40 – 28 ka ago), Gravettian (28 – 21 ka ago), Solutrean (21 – 17 ka ago) and Magdalenian (17 – 11.5 ka ago).[1]

Aurignacian

The first phase of Aurignacian or Mode 4, sometimes called archaic Aurignacian or proto-Aurignacian, is contemporary with late Châtelperronian findings and still shares many lithic tools with Mode 3. It is mainly found in northern Iberia (current Cantabria, Asturias, Basque Country and Catalonia).[16] Around 36 ka ago, it becomes more differentiated and can also be found scarcely in Iberia's interior, maybe because of a second wave of Homo Sapiens coming from Europe. The most common findings are antler or bone assegais, along fine flint blades and long scrapers. Mode 4 becomes finally consolidated around 31 ka ago and archaeological sites are found scattered through all of Iberia.[1]

Some examples of Aurignacian archaeological sites are: Cave of Morín (Cantabria), Cave of El Pendo (Cantabria), Cave of El Castillo (Cantabria), Santimamiñe (Basque Country), Gorham's Cave (Gibraltar), Cova de Les Mallaetes (Valencia) and Cave of Pego do Diablo (Lisbon). The remains of a child dated c. 24.5 years ago, known as the Lapedo child, were discovered in Lagar Velho (Leiria), presenting a mosaic of Homo sapiens and Neanderthal features. There is no academic consensus on whether the individual was an hybrid.[16][14] At the end of Aurignacian, Homo neanderthalensis has disappeared from Iberia.

Gravettian

The Gravettian expanded from eastern Europe to Iberia just as Aurignacian previously. However, during this period the last glacial maximum is reached and thus oriental and occidental Europe become isolated. This will imply that Gravettian will evolve later into Solutrean, whereas in easter Europe it isn't found.[1]

Its remains are not very abundant in the Cantabrian area (north), while in the southern region they are more common. In the Cantabrian area all Gravettian remains belong to late evolved phases and are found always mixed with Aurignacian technology. The main sites are found in the Basque Country (Lezetxiki, Bolinkoba), Cantabria (Morín, El Pendo, El Castillo) and Asturias (Cueto de la Mina). It is archaeologically split in two phases characterized by the amount of Gravettian elements: the phase A has a 14C date of c.20,710 BP and the phase B is of later date.

The Cantabrian Gravettian has been paralleled to the Perigordian V-VII of the French sequence. It eventually vanishes from the archaeological sequence and is replaced by an "Aurignacian renaissance", at least in El Pendo cave. It is considered "intrusive", in contrast with the Mediterranean area, where it probably means a real colonization.[17]

In the Mediterranean region, the Gravettian culture also had a late arrival. Nevertheless, the south-east has an important number of sites of this culture, especially in the Land of Valencia (Les Mallaetes, Parpaló, Barranc Blanc, Meravelles, Coba del Sol, Ratlla del Musol, Beneito). It is also found in the Land of Murcia (Palomas, Palomarico, Morote) and Andalusia (Los Borceguillos, Zájara II, Serrón, Gorham's Cave).

The first indications of modern human colonization of the interior and the west of the peninsula are found only in this cultural phase, with a few late Gravettian elements found in the Manzanares valley (Madrid) and Salemas cave (Alentejo).

Solutrean

The Solutrean culture shows its earliest appearances in Laugerie Haute (Dordogne, France) and Les Mallaetes (Land of Valencia), with radiocarbon dates of 21,710 and 20,890 BP respectively.[17] In the Iberian peninsula it shows three different facies:

The Iberian (or Mediterranean) facies is defined by the sites of Parpalló and Les Mallaetes in the province of Valencia. They are found immersed in important Gravettian perdurations that would eventually redefine the facies as "Gravettizing Solutrean."[17] The archetypical sequence, that of Parpalló and Les Mallaetes caves, is:

- Initial Solutrean.

- Full or Middle Solutrean, dated in its lower layers to 20,180 BP.

- A sterile layer with signs of intense cold that is related to the Last Glacial Maximum.

- Upper or Evolved Solutrean, including bone tools and also needles of this material.

These two caves are surrounded by many other sites (Barranc Blanc, Meravelles, Rates Penaes, etc.) that show only a limited impact of Solutrean and instead have many Gravettian perdurations, showing a convergence that has been named as "Gravetto-Solutrean".

Solutrean is also found in the Land of Murcia, Mediterranean Andalusia and the lower Tagus (Portugal). In the Portuguese case there are no signs of Gravettization.

The Cantabrian facies shows two markedly different tendencies in Asturias and the Vasco-Cantabrian area. The oldest findings are all in Asturias and lack of the initial phases, beginning with the full Solutrean in Las Caldas (Asturias) and other nearby sites, followed by evolved Solutrean, with many unique regional elements. Radiocarbon dates oscillate between 20,97 and 19 ka BP.[17]

In the Vasco-Cantabrian area instead the Gravettian influences seem persistent and the typical Solutrean foliaceous elements are minority. Some transitional elements that prelude the Magdalenian, like the monobiselated bone spear point, are already present. Most important sites are Altamira, Morín, Chufín, Salitre, Ermittia, Atxura, Lezetxiki, and Santimamiñe.

In northern Catalonia there is an early local Solutrean, followed by scarce middle elements but with a well-developed final Solutrean. It is related to the French Pyrenean sequences. Main sites are Cau le Goges, Reclau Viver and L'Arbreda.

In the region of Madrid there were some findings attributed to Solutrean that are today missing.

Magdalenian

This phase is defined by the Magdalenian culture, even if in the Mediterranean area the Gravettian influence is still persistent.

In the Cantabrian area, the early Magdalenian phases show two different facies: the "Castillo facies" evolves locally over final Solutrean layers, while the "Rascaño facies" appears in most cases directly over the natural soil (no earlier occupations of these sites).

In the second phase, the lower evolved Magdalenian, there are also two facies but now with a geographical divide: the "El Juyo facies" is found in Asturias and Cantabria, while the "Basque Country facies" is only found in this region.

The dates for this early Magdalenian period oscillate between 16,433 BP for Rascaño cave (Rascaño facies), 15,988 and 15,179 BP for the same cave (El Juyo facies) and 15 ka BP for Altamira (Castillo facies). For the Basque Country facies the cave of abauntz has given 15,800 BP.[17]

The middle Magdalenian shows less abundance of findings.

The upper Magdalenian is closely related to that of southern France (Magdalenian V and VI), being characterized by the presence of harpoons. Again there are two facies (called A and B) that appear geographically intertwined, though the facies A (dates: 15,400–13,870 BP) is absent in the Basque Country and the facies B (dates 12,869–12,282 BP) is rare in Asturias.

In Portugal there have been some findings of the upper Magdalenian north of Lisbon (Casa da Moura, Lapa do Suão). A possible intermediate site is La Dehesa (Salamanca), that is clearly associated with that of the Cantabrian area.

In the Mediterranean area, Catalonia again is directly connected with the French sequence, at least in the late phases. Instead the rest of the region shows a unique local evolution known as Parpallense.

The sometimes called Parpalló "Magdalenian" (extended by all the south-east) is actually a continuity of the local Gravetto-Solutrean. Only the late upper Magdalenian actually includes true elements of this culture, like proto-harpoons. Radicarbon dates for this phase are of c. 11,470 BP (Borran Gran). Other sites give later dates that actually approach the Epi-Paleolithic.[17]

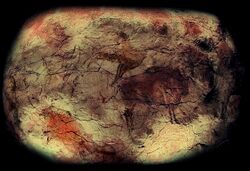

Art

Impressive Paleolithic cave and rock art has survived in Iberia until present day. Altamira cave is the most well-known example of the former, being a world heritage site since 1985.[18] The earliest manifestations, for example the Caves of Monte Castillo (Cantabria) are as old as Aurignacian times. L'Arbreda Cave in Catalonia contains Aurignacian cave paintings, as well as earlier remains from Neanderthals.

The practice of this mural art increases in frequency in the Solutrean period, when the first animals are drawn, but it is not until the Magdalenian cultural phase when it becomes truly widespread, being found in almost every cave.

Most of the representations are of animals (bison, horse, deer, bull, reindeer, goat, bear, mammoth, moose) and are painted in ochre and black colors but there are exceptions and human-like forms as well as abstract drawings also appear in some sites.

In the Mediterranean and interior areas, the presence of mural art is not so abundant but exists as well since the Solutrean.

Côa Valley, in current Portugal, and Siega Verde, in current Spain , formed around tributaries into Douro, contain the best preserved rock art, forming together another world heritage site since 1998.[19] They contain petroglyphs dating up to 22 ka years ago. These document continuous human occupation from the end of the Paleolithic Age. Hundreds of panels with thousands of animal figures were carved over several millennia, representing the most remarkable open-air ensemble of Paleolithic art on the Iberian Peninsula.[19]

Other examples include Chimachias, Los Casares or La Pasiega, or, in general, the caves principally in Cantabria.

See also

- Paleontology

- Timeline of human evolution

- Paleolithic religion

- Art of the Upper Paleolithic

- Art of the Middle Paleolithic

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Menéndez, Mario (2019). Prehistoria de la Península Ibérica : el progreso de la cognición, el mestizaje y las desigualdades durante más de un millón de años. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. ISBN 978-84-9181-602-7. OCLC 1120111673. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1120111673.

- ↑ Clark, Grahame (1977). World prehistory: In new perspective (An illustrated 3d ed.). Cambridge [Eng]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-21506-4. OCLC 2984089. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/2984089.

- ↑ "Archaeological Site of Atapuerca" (in en). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/989/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Prehistoria" (in es). National Geographic Institute (Spain). http://atlasnacional.ign.es/wane/Prehistoria.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Crespo Garay, Cristina (2021-11-27). "¿Qué homínidos han poblado España a lo largo de la historia?" (in es-es). National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.es/historia/que-hominidos-han-habitado-en-espana-a-lo-largo-de-la-historia.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Lorenzo, Carlos (2022). "Los homininos de Atapuerca. Caracterización y genética". Desperta Ferro Arqueología e Historia 45: 16–21. ISSN 2387-1237. https://despertaferro-ediciones.com/revistas/numero/arqueologia-e-historia-45-atapuerca-prehistoria/.

- ↑ "Encuentran en Atapuerca la cara del Primer Europeo" (in es-es). https://www.atapuerca.org/es/ficha/ZB0E4E1F1-AF49-B47F-68B4E90B14BC706A/encuentran-en-atapuerca-la-cara-del-primer-europeo.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 García Medrano, Paula (2022). "Tecnología y evolución de las herramientas en Atapuerca" (in European Spanish). Desperta Ferro Arqueología e Historia 45: 50–55. ISSN 2387-1237. https://www.despertaferro-ediciones.com/revistas/numero/arqueologia-e-historia-45-atapuerca-prehistoria/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Mosquera Martínez, Marina (2022). "El comportamiento social de los homininos". Desperta Ferro Arqueología e Historia 45: 30–37. ISSN 2387-1237. https://www.despertaferro-ediciones.com/revistas/numero/arqueologia-e-historia-45-atapuerca-prehistoria/.

- ↑ Carbonell i Roura, Eudald (2022). "Atapuerca. Historia y futuro". Desperta Ferro Arqueología e Historia 45: 6–15. ISSN 2387-1237. https://www.despertaferro-ediciones.com/revistas/numero/arqueologia-e-historia-45-atapuerca-prehistoria/.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Roussel, M.; Soressi, M.; Hublin, J. -J. (2016-06-01). "The Châtelperronian conundrum: Blade and bladelet lithic technologies from Quinçay, France" (in en). Journal of Human Evolution 95: 13–32. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.003. ISSN 0047-2484.

- ↑ "Gruta do Escoural". DGPC. https://arqueologia.patrimoniocultural.pt/index.php?sid=sitios&subsid=54576.

- ↑ Garrod, Dorothy A. E.; Buxton, L. H.; Smith, E. Elliot; Bate, Dorothea M. A. (1928). "Excavation of a Mousterian Rock-shelter at Devil's Tower, Gibraltar". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland) 58: 33–113.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ian Tattersall, Jeffrey H. Schwartz (22 June 1999). "Hominids and hybrids: The place of Neanderthals in human evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (National Academy of Sciences) 96 (13): 7117–7119. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7117. PMID 10377375. Bibcode: 1999PNAS...96.7117T.

- ↑ "Gruta de Salemas" (in pt). Portal do Arqueólogo. IGESPAR. http://arqueologia.igespar.pt/index.php?sid=sitios.resultados&subsid=54492&vt=120614.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Duarte, Cidália; Maurício, João; Pettitt, Paul B.; Souto, Pedro; Trinkaus, Erik; van der Plicht, Hans; Zilhão, João (1999-06-22). "The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern human emergence in Iberia" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96 (13): 7604–7609. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 10377462.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 F. Jordá Cerdá et al., Historia de España I: Prehistoria, 1986. ISBN:84-249-1015-X

- ↑ "Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain" (in en). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/310/.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Prehistoric Rock Art Sites in the Côa Valley and Siega Verde". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/866.

External links

- Lower Paleolithic map of Iberia from the National Geographic Institute of Spain (in spanish)

- Middle Paleolithic map of Iberia from the National Geographic Institute of Spain (in spanish)

- Upper Paleolithic map of Iberia from the National Geographic Institute of Spain (in spanish)

|