Engineering:Shenzhou (spacecraft)

A Shenzhou spacecraft undergoing ground testing without solar panels | |

| Manufacturer | CAST |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | |

| Operator | CMSA |

| Applications | Crewed spaceflight |

| Specifications | |

| Design life | Up to 183 days (docked at the Tiangong space station) |

| Launch mass | 8100 kg[1] |

| Crew capacity | 3 |

| Dimensions | 9.25 x 2.8 m |

| Volume | 14.8 m3[1] habitable: 7.0 m3 |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Dimensions | |

| Production | |

| Status | In service |

| Built | 17 |

| On order | 1 |

| Launched | 17 |

| Operational | 1 |

| Failed | 0 |

| Maiden launch | Shenzhou 1: 19 November 1999 (uncrewed) Shenzhou 5: 15 October 2003 (crewed) |

| Last launch | Active Shenzhou 17: 26 October 2023 (crewed) |

Shenzhou (Chinese: 神舟; pinyin: Shénzhōu, /ˈʃɛnˈdʒoʊ/;[2] see § Etymology) is a spacecraft developed and operated by China to support its crewed spaceflight program, China Manned Space Program. Its design resembles the Russian Soyuz spacecraft, but it is larger in size. The first launch was on 19 November 1999 and the first crewed launch was on 15 October 2003. In March 2005, an asteroid was named 8256 Shenzhou in honour of the spacecraft.

Etymology

The literal meaning of the native name 神舟 (p: Shénzhōu; /ˈʃɛnˈdʒoʊ/[2]) is "the Divine vessel [on the Heavenly River]", to which Heavenly River (天河) means the Milky Way in Classical Chinese.[3] 神舟 is a pun and neologism that plays on the poetic word referring to China, 神州,[3] meaning Divine realm,[4] which bears the same pronunciation. For further information, refer to Chinese theology, Chinese astronomy and names of China.

History

China's first efforts at human spaceflight started in 1968 with a projected launch date of 1973.[5] Although China successfully launched an uncrewed satellite in 1970, its crewed spacecraft program was cancelled in 1980 due to a lack of funds.[6]

The Chinese crewed spacecraft program was relaunched in 1992 with Project 921. The Phase One spacecraft followed the general layout of the Russian Soyuz spacecraft, with three modules that could separate for reentry. China signed a deal with Russia in 1995 for the transfer of Soyuz technology, including life support and docking systems. The Phase One spacecraft was then modified with the new Russian technology.[6] The general designer of Shenzhou-1 through Shenzhou-5 was Qi Faren (戚发轫, 26 April 1933), and from Shenzhou-6 on, the general design was turned over to Zhang Bainan (张柏楠, 23 June 1962).[citation needed]

The first uncrewed flight of the spacecraft was launched on 19 November 1999, after which Project 921/1 was renamed Shenzhou, a name reportedly chosen by Jiang Zemin.[citation needed] A series of three additional uncrewed flights were carried out. The first crewed launch took place on 15 October 2003 with the Shenzhou 5 mission. The spacecraft has since become the mainstay of the Chinese crewed space program, being used for both crewed and uncrewed missions.

Design

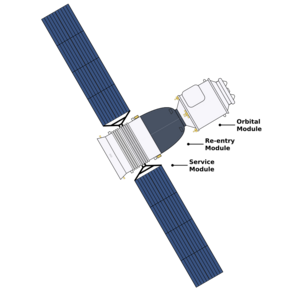

Shenzhou consists of three modules: a forward orbital module (轨道舱), a reentry module (返回舱) in the middle, and an aft service module (推进舱). This division is based on the principle of minimizing the amount of material to be returned to Earth. Anything placed in the orbital or service modules does not require heat shielding, increasing the space available in the spacecraft without increasing weight as much as it would if those modules were also able to withstand reentry.

- Complete spacecraft data

- Total mass: 7,840 kilograms (17,280 lb)

- Length: 9.25 metres (30.3 ft)

- Diameter: 2.80 metres (9.2 ft)

- Span: 17 metres (56 ft)

Orbital module

The orbital module (轨道舱) contains space for experiments, crew-serviced or crew-operated equipment, and in-orbit habitation. Without docking systems, Shenzhou 1–6 carried different kinds of payload on the top of their orbital modules for scientific experiments.

The Chinese spacecraft docking mechanism (beginning with Shenzhou 8) is based on the Androgynous Peripheral Attach System (APAS).[7]

Up until Shenzhou 8, the orbital module of the Shenzhou was equipped with its own propulsion, solar power, and control systems, allowing autonomous flight. It is possible for Shenzhou to leave an orbital module in orbit for redocking with a later spacecraft, a capability which Soyuz does not possess, since the only hatch between the orbital and reentry modules is a part of the reentry module, and orbital module is depressurized after separation. For future missions, the orbital module(s) could also be left behind on the planned Chinese project 921/2 space station as additional station modules.

In the uncrewed test flights launched, the orbital module of each Shenzhou was left functioning on orbit for several days after the reentry modules return, and the Shenzhou 5 orbital module continued to operate for six months after launch.

- Orbital module data

- Design life: 200 days

- Length: 2.80 metres (9.2 ft)

- Basic diameter: 2.25 metres (7.4 ft)

- Maximum diameter: 2.25 metres (7.4 ft)

- Span: 10.4 metres (34 ft)

- Habitable volume: 8 cubic metres (280 cu ft)

- Mass: 1,500 kilograms (3,300 lb)

- RCS Coarse No x Thrust: 16 x 5 N

- RCS Propellants: Hydrazine

- Electrical system: Solar panels, 12.24 square metres (131.8 sq ft)

- Electric system: 0.50 average kW

- Electric system: 1.20 kW

Reentry module

The reentry module (返回舱) is located in the middle section of the spacecraft and contains seating for the crew. It is the only portion of Shenzhou which returns to Earth's surface. Its shape is a compromise between maximizing living space and allowing for some aerodynamic control upon reentry.

Reentry module data

- Crew size: 3

- Design life: 20 days (original)

- Length: 2.5 metres (8.2 ft)

- Basic diameter: 2.52 metres (8.3 ft)

- Maximum diameter: 2.52 metres (8.3 ft)

- Habitable volume: 6 cubic metres (210 cu ft)

- Mass: 3,240 kilograms (7,140 lb)

- Heat shield mass: 450 kilograms (990 lb)

- Lift-to-drag-ratio (hypersonic): 0.30

- RCS Coarse No x Thrust: 8 x 150 N

- RCS Propellants: Hydrazine

Service module

The aft service module (推进舱) contains life support and other equipment required for the functioning of Shenzhou. Two pairs of solar panels, one pair on the service module and the other pair on the orbital module, have a total area of over 40 square metres (430 sq ft), indicating average electrical power over 1.5 kW (Soyuz have 1.0 kW).

Service module data

- Design life: 20 days

- Length: 2.94 metres (9.6 ft)

- Basic diameter: 2.5 metres (8.2 ft)

- Maximum diameter: 2.8 metres (9.2 ft)

- Span: 17 metres (56 ft)

- Mass: 3,000 kilograms (6,600 lb)

- RCS Coarse No x Thrust: 8 x 150 N

- RCS Fine No x Thrust: 16 x 5 N

- RCS Propellants: N2O4 / MMH, unified system with main engine

- Main engine: 4 x 2500 N

- Main engine thrust: 10.000 kN (2,248 lbf)

- Main engine propellants: N2O4 / MMH

- Main engine propellants: 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb)

- Main engine Isp: 290 seconds

- Electrical system: Solar panels, 24.48 + 12.24 m2 (263.5 + 131.8 sq ft), 36.72 m2 (395.3 sq ft) total

- Electric system: 1.50 average kW

- Electric system: 2.40 kW

Comparison with Soyuz

Although the Shenzhou spacecraft follows the same layout as the Russian Soyuz spacecraft, it is approximately 10% larger and heavier than Soyuz. It also has a bigger cylindrical orbital module and 4 propulsion engines. There is enough room to carry an inflatable raft in case of a splashdown, whereas Soyuz astronauts must jump into the water and swim. The commander sits in the center seat on both spacecraft. However, the copilot sits in the left seat on Shenzhou and the right seat on Soyuz.[8]

Launch records

The records information is all from Gunter's space page.[9] All times are in Coordinated Universal Time.

| Number | Launch time | Return time | Crew | Flight duration | Orbits | Launch location | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shenzhou 1 | 19 November 1999, 22:30 | 20 November 1999, 19:41 | None | 21 hours, 11 minutes | 14 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 2 | 9 January 2001, 17:00 | 16 January 2001, 11:22 | None | 6 days, 18 hours, 22 minutes | 108 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 3 | 25 March 2002, 14:15 | 1 April 2002, 08:51 | None | 6 days, 18 hours, 51 minutes | 108 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 4 | 29 December 2002, 16:40 | 5 January 2003, 11:16 | None | 6 days, 18 hours, 36 minutes | 108 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 5 | 15 October 2003, 01:00 | 15 October 2003, 22:22 | Yang Liwei | 21 hours, 22 minutes, | 14 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 6 | 12 October 2005, 01:00 | 16 October 2005, 20:33 | Fei Junlong, Nie Haisheng | 4 days, 19 hours, 33 minutes | 77 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 7 | 25 September 2008, 13:10 | 28 September 2008, 09:37 | Zhai Zhigang, Liu Boming, Jing Haipeng | 2 days, 20 hours, 27 minutes | 45 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 8 | 31 October 2011, 21:58 | 17 November 2011, 11:32 | None | 17 days, 13 hours, 34 minutes | 249 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 9 | 16 June 2012, 10:37 | 29 June 2012, 02:01 | Jing Haipeng, Liu Wang, Liu Yang | 12 days, 15 hours, 24 minutes | 198 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 10 | 11 June 2013, 09:38 | 26 June 2013, 00:07 | Nie Haisheng, Zhang Xiaoguang, Wang Yaping | 14 days, 14 hours, 29 minutes | 229 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 11 | 16 October 2016, 23:30 | 18 November 2016, 05:59 | Jing Haipeng, Chen Dong | 32 days, 6 hours, 29 minutes | 507 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 12 | 17 June 2021, 01:22 | 17 September 2021, 05:34 | Nie Haisheng, Liu Boming, Tang Hongbo | 92 days, 4 hours, 11 minutes | 1454 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 13 | 15 October 2021, 16:23 | 16 April 2022, 01:56 | Zhai Zhigang, Wang Yaping, Ye Guangfu | 182 days, 9 hours, 32 minutes | 2885 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 14 | 5 June 2022, 02:44 | 4 December 2022, 12:09 | Chen Dong, Liu Yang, Cai Xuzhe | 182 days, 9 hours, 25 minutes | 2885 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 15 | 29 November 2022, 15:08 | 3 June 2023, 22:33 | Fei Junlong, Deng Qingming, Zhang Lu | 186 days, 7 hours, 25 minutes | 2931 | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 16 | 30 May 2023, 09:31 | 31 October 2023, 00:12 | Jing Haipeng, Zhu Yangzhu, Gui Haichao | 153 days, 22 hours and 41 minutes | ? | Jiuquan LA-4 | Success |

| Shenzhou 17 | 26 October 2023, 03:14 | April 2024 | Tang Hongbo, Tang Shengjie, Jiang Xinlin | 180 days (planned) | Currently in orbit | Jiuquan LA-4 | Docked at Tiangong |

In popular culture

- The Shenzhou was prominently featured in the film Gravity and was used by the main character, STS-157 Mission Specialist Dr. Ryan Stone, to safely return home after the destruction of her spacecraft.[10][11]

- In Star Trek: Discovery, the Walker class starship USS Shenzhou is named after this spacecraft.[12]

See also

- 863 Program

- Beihang University

- Chinese next-generation crewed spacecraft

- Harbin Institute of Technology

- Long March (rocket family)

- Names of China

- Shuguang

- Tiangong program

- List of human spaceflights to the Tiangong space station

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 朱光辰 (2022). "我国载人航天器总体构型技术发展". 航天器工程 第31卷 (第6期): 47. http://www.htgc.cbpt.cnki.net/WKE/WebPublication/paperDigest.aspx?paperID=645e2201-f29d-4e4a-93d5-e988773274f0#.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Shenzhou pronunciation". http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/shenzhou.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 樊永强 (23 September 2008). "中国载人航天飞船为何命名"神舟"号?". Xinhua News. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080927221409/http://news.xinhuanet.com/newscenter/2008-09/23/content_10099263.htm.

- ↑ Hughes, April D. (2021). Worldly Saviors and Imperial Authority in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. p. 103. "Attesting Illumination states that two saviors will manifest in the Divine Realm (shenzhou 神州; i.e. China) 799 years after Śākyamuni Buddha's nirvāṇa."

- ↑ Mark Wade (2009). "Shuguang 1". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/shuuang1.htm.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Futron Corp. (2003). "China and the Second Space Age". Futron Corporation. http://www.futron.com/upload/wysiwyg/Resources/Whitepapers/China_n_%20Second_Space_Age_1003.pdf.

- ↑ "ISS Interface Mechanisms and their Heritage". Houston, Texas: Boeing. 1 January 2011. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20110010964.pdf. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ Hollingham, Richard (27 June 2018). "Why Europe's astronauts are learning Chinese" (in en). BBC Future. http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20180626-why-europes-astronauts-are-learning-chinese.

- ↑ "Shenzhou Flight History". https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sat/shenzhou_hist.htm.

- ↑ Kramer, Miriam (6 October 2013). "The Spaceships of 'Gravity': A Spacecraft Movie Guide for Astronauts". Yahoo. https://news.yahoo.com/spaceships-gravity-spacecraft-movie-guide-astronauts-133510136.html.

- ↑ Lyons, Lauren (19 October 2013). ""Gravity", China and the end of American Exceptionalism in outer space". Spaceflight Insider. http://spaceflightinsider.com/space-flight-news/astronauts/gravity-china-and-the-end-of-american-excepionalism-in-outer-space/.

- ↑ "Shenzhou NCC-1227, U.S.S.". CBS Entertainment. https://intl.startrek.com/database_article/shenzhou-ncc-1227-u-s-s.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shenzhou. |

- "China's first astronaut revealed". BBC. 7 March 2003. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/2829349.stm.

- "China's Manned Space Program: Trajectory and Motivations". http://www.cns.miis.edu/pubs/week/031006.htm.

- "Details on purchase of Soyuz descent capsule by China". http://www.space.com/news/china_russia_991122.html.

External links

- Flickr: Photos tagged with shenzhou, photos likely relating to Shenzhou spacecraft

- Subsystems and Project management of Shenzhou 7

|