Engineering:Dragon 2

Crew Dragon C201 approaching the ISS in March 2019, during SpaceX Demo-1 | |

| Manufacturer | SpaceX |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Operator | SpaceX |

| Applications | ISS crew and cargo transport |

| Specifications | |

| Design life | |

| Dry mass | 9,525 kg (20,999 lb)[3] |

| Payload capacity | |

| Crew capacity | 7 / 4 (NASA seat usage) |

| Dimensions | |

| Volume |

|

| Production | |

| Status | Testing |

| Built | 3 (2 test article, 1 production) |

| Launched | 2 |

| Maiden launch | 2 March 2019[6] |

| Last launch | 19 January 2020 |

| Related spacecraft | |

| Derived from | SpaceX Dragon |

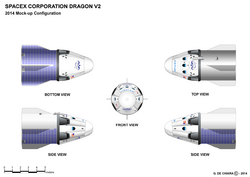

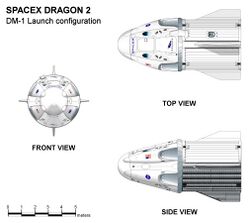

Dragon 2 is a class of reusable spacecraft developed and manufactured by U.S. aerospace manufacturer SpaceX, intended as the successor to the Dragon cargo spacecraft. The spacecraft launches atop a Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket and returns via ocean splashdown. When compared to Dragon, Crew Dragon has larger windows, new flight computers and avionics, redesigned solar arrays, and a modified outer mold line.

The spacecraft has two planned variants – Crew Dragon, a human-rated capsule capable of carrying up to seven astronauts, and Cargo Dragon, an updated replacement for the original Dragon. Crew Dragon is equipped with an integrated launch escape system in a set of four side-mounted thruster pods with two SuperDraco engines each. Crew Dragon has been contracted to supply the International Space Station (ISS) with crew under the Commercial Crew Program, with the initial award occurring in October 2014 alongside Boeing CST-100 Starliner. Crew Dragon's first non-piloted test flight to the ISS launched in March 2019.

Cargo Dragon will supply the ISS with cargo under the Commercial Resupply Services-2 (CRS-2) after a January 2016 selection alongside Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems' Cygnus and Sierra Nevada Corporation's Dream Chaser. SpaceX's first CRS-2 mission with the Cargo Dragon is slated to occur in August 2020 after SpaceX's final CRS-20 mission with the original Dragon spacecraft.[7]

The Crew Dragon capsule that flew in the first test flight was scheduled to be used in a flight abort test before it unexpectedly exploded during a test of its SuperDraco engines on 20 April 2019. An investigation into the explosion was completed on 15 July 2019 and resulted in changes to vehicle plumbing.[8]

The in-flight abort test was conducted on 19 January 2020 at 15:30 UTC. The first crewed launch is scheduled for April 2020.[9]

Development and variants

There are two variants: Crew Dragon and Cargo Dragon.[5] Crew Dragon was initially called DragonRider[10][11] and it was intended from the beginning to support a crew of seven or a combination of crew and cargo.[12][13] It is able to perform fully autonomous rendezvous and docking with manual override ability using the NASA Docking System (NDS).[14][15] For typical missions, Crew Dragon will remain docked to the ISS for a period of 180 days, but is designed to remain on the station for up to 210 days, matching the Russian Soyuz spacecraft.[16][17][18] From the beginning of the development process, SpaceX planned to use an integrated pusher launch escape system for the Dragon spacecraft.[19][20][21]

SpaceX originally intended to land Crew Dragon on land using the LES engines, with parachutes and an ocean splashdown available in the case of an aborted launch. Precision water landing under parachutes was proposed to NASA as "the baseline return and recovery approach for the first few flights" of Crew Dragon.[22] Propulsive landing was later cancelled, leaving ocean splashdown under parachutes as the only option.[23] As of 2011[update], the Paragon Space Development Corporation was assisting in developing Crew Dragon's life support system.[24]

In 2012, SpaceX was in talks with Orbital Outfitters about developing space suits to wear during launch and re-entry.[25] Each crew member wears a custom space suit fitted for them. The suit is primarily designed for use inside the Dragon (IVA type suit), however in the case of a rapid cabin depressurization the suit can protect the crew members. The suit can also provide cooling for astronauts during normal flight. [26][27] For the SpX-DM1 test, a test dummy nicknamed Ripley was fitted with the spacesuit and sensors. The spacesuit "is made from Nomex" a fire retardant fabric similar to Kevlar.

At a NASA news conference on 18 May 2012, SpaceX confirmed their target launch price for crewed Dragon flights of $160 million, or about $20 million per seat if the maximum crew of 7 is aboard and NASA orders at least four Crew Dragon flights per year.[28] This contrasts with the 2014 Soyuz launch price of $76 million per seat for NASA astronauts.[29] The spacecraft's design was unveiled on 29 May 2014, during a press event at SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California.[30][31][32] In October 2014, NASA selected the Dragon spacecraft as one of the candidates to fly American astronauts to the International Space Station under the Commercial Crew Program.[33][34][35] SpaceX plans to use the Falcon 9 Block 5 launch vehicle for launching Dragon 2.[4]

Technical specifications

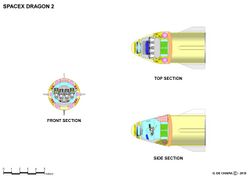

Dragon 2 includes the following features:[30][31][36] Dragon 2 is partially reusable, potentially resulting in a significant cost reduction. SpaceX plans to use new capsules for every crewed flight for NASA.[37] Cargo Dragon can carry 3,307 kilograms (7,291 lb) to the ISS; Crew Dragon has a capacity of seven astronauts (only four seats are used for NASA missions). Above the seats, there is a three-screen control panel, a toilet (with privacy curtain) and the docking hatch. Ocean landings are accomplished with four main parachutes in both variants. The parachute system was fully redesigned from the one used in the prior Dragon capsule, due to the need to deploy the parachutes under a variety of launch abort scenarios.[38]

Crew Dragon has eight side-mounted SuperDraco engines, clustered in redundant pairs in four engine pods, with each engine able to produce 71 kilonewtons (16,000 lbf) of thrust to be used for launch aborts.[30] Each pod also contains four Draco thrusters that can be used for attitude control and orbital maneuvers. The SuperDraco engine combustion chamber is printed of Inconel, an alloy of nickel and iron, using a process of direct metal laser sintering. Engines are contained in a protective nacelle to prevent fault propagation if an engine fails.

Once on orbit, Dragon 2 is able to autonomously dock to the ISS. Dragon used berthing, a non-autonomous means to attach to the ISS that was completed by use of the Canadarm2 robotic arm. Pilots of Crew Dragon retain the ability to dock the spacecraft using manual controls interfaced with a static tablet-like computer. The spacecraft can be operated in full vacuum, and "the crew will wear SpaceX-designed space suits to protect them from a rapid cabin depressurization emergency event". Also, the spacecraft will be able to return safely if a leak occurs "of up to an equivalent orifice of 0.25 inches [6.35 mm] in diameter."[22]

Propellant and helium pressurant for both launch aborts and on-orbit maneuvering is contained in composite-carbon-overwrap titanium spherical tanks. A PICA-X heat shield protects the capsule during reentry, while a movable ballast sled allows more precise attitude control of the spacecraft during the atmospheric entry phase of the return to Earth and more accurate control of the landing ellipse location.[22] A reusable nose cone "protects the vessel and the docking adaptor during ascent and reentry",[22] pivoting on a hinge to enable in-space docking and returning to the covered position for reentry and future launches[32]

The trunk is the third structural element of the spacecraft, containing solar panels, heat-removal radiators, and fins to provide aerodynamic stability during emergency aborts.[22]

The previous Cargo Dragon’s deployable solar arrays have been eliminated and are now built into the trunk itself. This increases volume space, reduces the number of mechanisms on the vehicle and further increases reliability.

Planned crewed flights

Dragon is intended to fulfill a set of requirements that will make the capsule useful to both commercial and government customers. SpaceX and Bigelow Aerospace are working together to support round-trip transport of commercial passengers to low Earth orbit (LEO) destinations, using the full capacity of seven passengers. NASA flights to the ISS will only have four astronauts, with the added payload mass and volume used to carry pressurized cargo.[38]

On 16 September 2014, NASA announced that SpaceX and Boeing had been selected to provide crew transportation to the ISS. SpaceX will receive $2.6 billion under this contract.[39] Dragon was the least expensive proposal,[34] but NASA's William H. Gerstenmaier considers the CST-100 proposal the stronger of the two.

In a departure from the prior NASA practice, where construction contracts with commercial firms led to direct NASA operation of the spacecraft, NASA is purchasing space transport services from SpaceX, including construction, launch, and operation of the Dragon 2.[40]

In August 2018, NASA and SpaceX agreed on the loading procedures for propellants, vehicle fluids and crew. High-pressure helium will be loaded first, followed by the passengers approximately two hours prior to scheduled launch; the ground crew will then depart the launch pad and move to a safe distance. The launch escape system will be activated approximately 40 minutes prior to launch, with propellant loading commencing several minutes later.[41] The first automated test mission launched to the International Space Station (ISS) on 2 March 2019.[42]

In early 2019, crewed flights were expected to begin no earlier than July 2019,[43] which are now planned to begin no earlier than April 2020[44] with the launch of the Demo-2 mission.

In June 2019, Bigelow Space Operations announced it had reserved with SpaceX up to 4 missions of 4 passengers each to ISS as early as 2020 and plans to sell them for around $52 million per seat.[45] These plans were canceled by September 2019.

Testing

SpaceX planned a series of four flight tests for the Crew Dragon - a "pad abort" test, an uncrewed orbital flight to the ISS, an in-flight abort test, and finally a 14-day crewed demonstration mission to the ISS,[46] which was initially planned for July 2019,[43] but after a Dragon capsule explosion, was delayed to January 2020 at the earliest[47].

Pad abort and hover tests

The pad abort test was conducted successfully on 6 May 2015 at SpaceX's leased SLC-40.[38] Dragon landed safely in the ocean to the east of the launchpad 99 seconds after ignition of the SuperDraco engines.[48] While a flight-like Dragon 2 and trunk were used for the pad abort test, they rested atop a truss structure for the test rather than a full Falcon 9 rocket. A crash test dummy embedded with a suite of sensors was placed inside the test vehicle to record acceleration loads and forces at the crew seat, while the remaining six seats were loaded with weights to simulate full-passenger-load weight.[40][49] The test objective was to demonstrate sufficient total impulse, thrust and controllability to conduct a safe pad abort. A fuel mixture ratio issue was detected after the flight in one of the eight SuperDraco engines, but did not materially affect the flight.[50][51]

On 24 November 2015, SpaceX conducted a test of Dragon 2's hovering abilities at the firm's rocket development facility in McGregor, Texas. In a video, the spacecraft is shown suspended by a hoisting cable and igniting its SuperDraco engines to hover for about 5 seconds, balancing on its 8 engines firing at reduced thrust to compensate exactly for gravity.[52] The test vehicle was the same capsule that performed the pad abort test earlier in 2015; it was nicknamed DragonFly.[53]

Demo-1: orbital flight test

In 2015, NASA named its first Commercial Crew astronaut cadre of four veteran astronauts to work with SpaceX and Boeing – Robert Behnken, Eric Boe, Sunita Williams, and Douglas Hurley.[54] The Crew Dragon Demo-1 mission will complete the last milestone of the Commercial Crew Development program, paving the way to starting commercial services under an upcoming ISS Crew Transportation Services contract.[40][55] On 3 August 2018, NASA announced the crew for the DM-2 mission.[56] The crew of two will be formed by NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley. Behnken previously flew as mission specialist on the STS-123 and the STS-130 missions. Hurley previously flew as a pilot on the STS-127 mission and on the final Space Shuttle mission, the STS-135 mission.

The first orbital test of Crew Dragon was an uncrewed mission, designated Crew Dragon Demo-1[40] and launched on 2 March 2019.[6][57] The spacecraft tested the approach and automated docking procedures with the ISS,[58] remained docked until 8 March 2019, then conducted the full re-entry, splashdown and recovery steps to qualify for a crewed mission.[59][60] Life-support systems were monitored all along the test flight. The same capsule was planned to be re-used in June for an in-flight abort test before it exploded on 20 April 2019.[6][61]

Explosion during testing

On 20 April 2019, the Crew Dragon capsule used in the Crew Dragon Demo-1 mission was destroyed in an explosion during static fire testing at the Landing Zone 1 facility.[62][63] On the day of the explosion, the initial testing of the Crew Dragon's Draco thrusters was successful, with the accident occurring during the test of the SuperDraco abort system.[64]

Telemetry, high-speed camera footage, and analysis of recovered debris indicate the problem occurred when a small amount of nitrogen tetroxide leaked into a helium line used to pressurize the propellant tanks. The leakage apparently occurred during pre-test processing. As a result, the pressurization of the system 100 ms before firing damaged a check valve and resulted in the explosion.[65][64]

Since the destroyed capsule had been slated for use in the upcoming in-flight abort test, the explosion and investigation delayed that test and the subsequent crewed orbital test.[66]

The SuperDraco engine test that failed on 20 April 2019, was repeated successfully on 13 November 2019. The full duration static fire test of Crew Dragon’s launch escape system took place at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station at SpaceX's Landing zone 1 at 20:08 UTC. The test was successful, showing that the modifications made to the vehicle to prevent a failure like the one that happened 20 April were successful. The vehicle used for this ground test will also be used for the following in-flight abort test.[67]

Some of the modifications are :

- Replacement of the valves with burst disks: Unlike valves, burst disks are designed for single use.

- Adding of flaps on each SuperDracos in order to reseal those thrusters prior to splashdown in the Ocean, preventing water intrusion and make Crew Dragon far easier to refurbish and reuse, also preventing Dragon from sinking.[68]

In-Flight Abort Test (IFAT)

SpaceX conducted an in-flight abort test from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A in Florida on 19 January 2020 at 15:30 UTC. The Crew Dragon test capsule was launched in an atmospheric flight to conduct a separation and abort scenario in the troposphere at transonic velocities, at max Q, where the vehicle experiences maximum aerodynamic pressure.[69] The test objective was to demonstrate the ability to safely move away from the ascending rocket under the most challenging atmospheric conditions of the flight trajectory, imposing the worst structural stress of a real flight on the rocket and spacecraft.[38] The abort test was performed using a regular Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket.[70]

Earlier, this test had been scheduled before the uncrewed orbital test,[71] however, SpaceX and NASA considered it safer to use a flight representative capsule rather than the test article from the pad abort test.[72]

Demo-2: Crew orbital flight test

Currently targeting April 2020[73], Demo-2 will be the first launch carrying crew.

List of spacecraft

Crew Dragon units and mission assignments after the 20 April 2019 explosion that destroyed C201.[74]

| Serial Number[75] | Assignment |

|---|---|

| C201 | Crew Dragon Demo-1 and, destroyed during preliminary testing for IFAT |

| C202, C203, C204 | Test articles |

| C205 | used in in-flight abort test |

| C206 | Crew Dragon Demo-2 |

| C207 | CCtCap-1 |

| C208-212 (?) | CCtCap-2 - CCtCap-6 (?) |

List of flights

List includes only completed or currently manifested missions. Launch dates are listed in UTC.

| Mission | Capsule №[76] | Launch date (UTC) | Remarks | Time at ISS (dd:hh:mm) |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dragon 2 pad abort test | DragonFly | 6 May 2015 | Pad abort test, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida | N/A | Success[77] |

| Crew Dragon Demo-1 | C204 | 2 March 2019[6] | Uncrewed test flight of the Crew Dragon capsule; docked 3 March 2019, 08:51 UTC; departed 8 March 2019, 05:32 UTC | 04:21:17 | Success |

| Crew Dragon in-flight abort test | C205 | 19 January 2020[78] | Used the capsule originally planned for Crew Dragon Demo-2.[79] | N/A | Success |

| Crew Dragon Demo-2 | C206 | April 2020 [80] | Crewed test flight with two astronauts for two weeks. Will use the capsule planned for the first operational crew mission.[79] | TBA | Planned |

| USCV-1 | C207 | July 2020 | Pending success of Demo-2, NASA has contracted six operational crewed flights.[81] First one will deliver ISS Expedition 64/65 crew consisting of Mike Hopkins, Victor Glover, and Japanese Soichi Noguchi. |

~6 months | Planned |

| CCtCap missions 2–6 | After 2020 | NASA has contracted six operational flights to carry up to four astronauts and 220 pounds of cargo to the ISS.[81] | Planned | ||

| CRS-2 missions 1–6 | 2020–2024[82] | Six more Cargo Dragon launches under the CRS-2 contract.[82] | Planned |

See also

Other crewed orbital spacecraft

| Name | Country | Current status |

|---|---|---|

| CST-100 Starliner | United States | Being built by Boeing for the Commercial Crew Development program in competition with Crew Dragon and is scheduled for launch in 2020.[83] |

| Dream Chaser | United States | A cargo spaceplane being developed by Sierra Nevada Corporation for CRS-2 with a proposed crew variant. |

| Orel/Federatsiya | Russia | A reusable next-generation crewed spacecraft proposed in Russia in the late 2000s. The company building it is "striving to launch" it prior to 2024.[84] |

| Soyuz (spacecraft) | Russia | Crewed spacecraft currently in use by Russia. |

| Gaganyaan | India | Crewed orbital spacecraft scheduled for 2021.[85] |

| Orion | United States | Crewed spacecraft being built for NASA by Lockheed Martin. Its first launch is scheduled for 2022. |

| Shenzhou | China | Crewed spacecraft currently in use by China. |

| Starship | United States | Crewed spacecraft being built by SpaceX company for orbital, Moon and Mars colonization missions. |

References

- ↑ "DragonLab datasheet" (PDF). Hawthorne, California: SpaceX. 8 September 2009. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110104010401/http://www.spacex.com/downloads/dragonlab-datasheet.pdf. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ↑ ""Commercial Crew Program American Rockets American Spacecraft American Soil" (page 15)". NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/commercialcrew_press_kit.pdf. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ↑ SpaceX, NASA Discuss Forthcoming Dragon Pad Abort Test

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 SpaceX (2019-03-01). "Dragon". https://www.spacex.com/dragon.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Audit of Commercial Resupply Services to the International Space Station. NASA. April 26, 2018. Report No. IG-18-016. Quote: "For SpaceX, certification of the company’s unproven cargo version of its Dragon 2 spacecraft for CRS-2 missions carries risk while the company works to resolve ongoing concerns related to software traceability and systems engineering processes."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "NASA, Partners Update Commercial Crew Launch Dates". NASA Commercial Crew Program Blog. February 6, 2019. https://blogs.nasa.gov/commercialcrew/2019/02/06/.

- ↑ https://spaceflightnow.com/launch-schedule/

- ↑ Shanklin, Emily (2019-07-15). "UPDATE: IN-FLIGHT ABORT STATIC FIRE TEST ANOMALY INVESTIGATION" (in en). https://www.spacex.com/news/2019/07/15/update-flight-abort-static-fire-anomaly-investigation.

- ↑ https://spaceflightnow.com/2020/01/17/falcon-9-crew-dragon-in-flight-abort-test-mission-status-center/

- ↑ "Final Environmental Assessment for Issuing an Experimental Permit to SpaceX for Operation of the DragonFly Vehicle at the McGregor Test Site, McGregor, Texas". Federal Aviation Administration. pp. 2–3. http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ast/media/DragonFly_Final_EA_sm.pdf. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ Gwynne Shotwell (March 21, 2014). Broadcast 2212: Special Edition, interview with Gwynne Shotwell (audio file). The Space Show. Event occurs at 24:05–24:45 and 28:15–28:35. 2212. Archived from the original (mp3) on March 22, 2014. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

we call it v2 for Dragon. That is the primary vehicle for crew, and we will retrofit it back to cargo.

- ↑ "Q+A: SpaceX Engineer Garrett Reisman on Building the World's Safest Spacecraft". PopSci. 13 April 2012. http://www.popsci.com/technology/article/2012-04/qa-former-astronaut-and-spacex-engineer-garrett-reisman-building-worlds-safest-spacecraft. Retrieved April 15, 2012. "DragonRider, SpaceX's crew-capable variant of its Dragon capsule"

- ↑ "SpaceX Completes Key Milestone to Fly Astronauts to International Space Station". SpaceX. October 20, 2011. http://www.spacex.com/press.php?page=20111020. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Dragon Overview". SpaceX. http://www.spacex.com/dragon.php. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ↑ Parma, George (20 March 2011). "Overview of the NASA Docking System and the International Docking System Standard" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111015075220/http://dockingstandard.nasa.gov/Documents/AIAA_ATS_NDS-IDSS_Overview_Draft1.pdf. Retrieved March 30, 2012. "iLIDS was later renamed the NASA Docking System (NDS), and will be NASA’s implementation of an IDSS compatible docking system for all future US vehicles"

- ↑ Bayt, Rob (July 16, 2011). "Commercial Crew Program: Key Driving Requirements Walkthrough". NASA. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120328055242/http://commercialcrew.nasa.gov/document_file_get.cfm?docid=107. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ Oberg, Jim (March 28, 2007). "Space station trip will push the envelope". NBC News. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/17815821. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ↑ Bolden, Charles (May 9, 2012). "2012-05-09_NASA_Response" (PDF). NASA. http://oiir.hq.nasa.gov/asap/documents/responses/nasa/2012-05-09_NASA_Response.pdf. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ With the exception of the Project Gemini spacecraft, which used twin ejection seats: "Encyclopedia Astronautica: Gemini Ejection" . Astronautix.com. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ↑ Chow, Denise (April 18, 2011). "Private Spaceship Builders Split Nearly $270 Million in NASA Funds". New York: Space.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2011. https://www.webcitation.org/6415KG6df?url=http://www.space.com/11421-nasa-private-spaceship-funding-astronauts.html. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Spaceship teams seek more funding" . MSNBC Cosmic Log. December 10, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Reisman, Garrett (February 27, 2015). "Statement of Garrett Reisman, Director of Crew Operations, Space Explorations Technologies Corp. (SpaceX) before the Subcommittee on Space, Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, U.S. House Of Representatives" (pdf). US House of Representatives, Committee on Science, Space, and Technology. http://science.house.gov/sites/republicans.science.house.gov/files/documents/HHRG-114-SY16-WState-GReisman-20150227.pdf. Retrieved February 28, 2015. (document source: SpaceX)

- ↑ "SpaceX Updates – Taking the next step: Commercial Crew Development Round 2". SpaceX. January 17, 2010. http://www.spacex.com/updates.php. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ↑ "In the news Paragon Space Development Corporation Joins SpaceX Commercial Crew Development Team". Paragon Space Development Corporation. June 16, 2011. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120107054003/http://www.paragonsdc.com/press_paragon-joins-spacex.php. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- ↑ Sofge, Eric (19 November 2012). "The Deep-Space Suit". PopSci. http://www.popsci.com/technology/article/2012-10/deep-space-suit. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ↑ "Dragon". https://www.spacex.com/dragon. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ↑ Gibbens, Sarah. "A First Look at the Spacesuits of the Future". National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com.au/space/a-first-look-at-the-spacesuits-of-the-future.aspx. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ↑ Star Wars: The Battle to Build the Next Shuttle: Boeing, SpaceX and Sierra Nevada. Bloomberg News. May 2014. Event occurs at 2:05. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ↑ "SpaceX scrubs launch to ISS over rocket engine problem". Deccan Chronicle. May 19, 2012. Archived from the original on May 23, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120523003837/http://www.deccanchronicle.com/channels/sci-tech/space/spacex-scrubs-launch-iss-over-rocket-engine-problem-933. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Norris, Guy (May 30, 2014). "SpaceX Unveils ‘Step Change’ Dragon ‘V2’". Aviation Week. http://aviationweek.com/space/spacex-unveils-step-change-dragon-v2. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Kramer, Miriam (May 30, 2014). "SpaceX Unveils Dragon V2 Spaceship, a Manned Space Taxi for Astronauts — Meet Dragon V2: SpaceX's Manned Space Taxi for Astronaut Trips". space.com. http://www.space.com/26063-spacex-unveils-dragon-v2-manned-spaceship.html. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Bergin, Chris (May 30, 2014). "SpaceX lifts the lid on the Dragon V2 crew spacecraft". NASAspaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2014/05/spacex-lifts-the-lid-dragon-v2-crew-spacecraft/. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Post, Hannah (2014-09-16). "NASA Selects SpaceX to be Part of America's Human Spaceflight Program". https://www.spacex.com/news/2014/09/16/nasa-selects-spacex-be-part-americas-human-spaceflight-program.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Oct 11; First, 2014 Guy Norris | AWIN. "Why NASA Rejected Sierra Nevada's Commercial Crew Vehicle" (in en). https://aviationweek.com/space/why-nasa-rejected-sierra-nevadas-commercial-crew-vehicle.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (June 9, 2017). "So SpaceX is having quite a year". Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/06/so-spacex-is-having-quite-a-year/. Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (2014-10-09). "NASA clears commercial crew contractors to resume work". Spaceflight Now. http://spaceflightnow.com/news/n1410/09cctcap/#.VDgLfBaum5d. Retrieved 2014-10-10. "a highly-modified second-generation Dragon capsule fitted with myriad upgrades and changes – including new rocket thrusters, computers, a different outer mold line, and redesigned solar arrays – from the company's Dragon cargo delivery vehicle already flying to the space station."

- ↑ Ralph, Eric (2018-08-28). "SpaceX has no plans to reuse Crew Dragon spaceships on NASA astronaut launches" (in en-US). https://www.teslarati.com/spacex-no-crew-dragon-spaceship-reuse-nasa-astronaut-launches/.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Bergin, Chris (2014-08-28). "Dragon V2 will initially rely on parachute landings". NASAspaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2014/08/dragon-v2-rely-parachutes-landing/. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ↑ "NASA Chooses American Companies to Transport U.S. Astronauts to International Space Station". http://www.nasa.gov/press/2014/september/nasa-chooses-american-companies-to-transport-us-astronauts-to-international/. Retrieved 2014-09-16.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Bergin, Chris (March 5, 2015). "Commercial crew demo missions manifested for Dragon 2 and CST-100". NASASpaceFlight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2015/03/commercial-crew-demo-missions-dragon-cst-100/. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ Garcia, Mark (2018-08-17). "NASA, SpaceX Agree on Plans for Crew Launch Day Operations" (in en). NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-spacex-agree-on-plans-for-crew-launch-day-operations/.

- ↑ "NASA's Commercial Crew Program Target Test Flight Dates". November 21, 2018. https://blogs.nasa.gov/commercialcrew/2018/11/21/nasas-commercial-crew-program-target-test-flight-dates-5/.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "NASA, Partners Update Commercial Crew Launch Dates". NASA Commercial Crew Program Blog. 6 February 2019. https://blogs.nasa.gov/commercialcrew/2019/02/06/.

- ↑ Chan, Athena (2020-01-02). "Elon Musk Shares Simulation Video, Schedule Of Crew Dragon’s First Crewed Flight". https://www.ibtimes.com/elon-musk-shares-simulation-video-schedule-crew-dragons-first-crewed-flight-2894125.

- ↑ "So, You Want to Be a Space Tourist?" (in en). 2019-06-11. https://observer.com/2019/06/international-space-station-commercial-business-tourism/.

- ↑ SpaceX's first crewed launch moved back to 2018

- ↑ "NASA sets tentative date for launching astronauts in SpaceX ship" (in en). https://futurism.com/the-byte/nasa-tentative-spacex-launch-date.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (May 6, 2015). "SpaceX crew capsule completes dramatic abort test". http://spaceflightnow.com/2015/05/06/spacex-crew-capsule-completes-dramatic-abort-test/. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (April 3, 2015). "SpaceX preparing for a busy season of missions and test milestones". NASASpaceFlight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2015/04/spacex-preparing-busy-season-missions-test-milestones/. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ↑ "SpaceX Crew Dragon pad abort: Test flight demos launch escape system". May 6, 2015. http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-050615a-spacex-dragon-pad-abort.html. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (May 6, 2015). "Dragon 2 conducts Pad Abort leap in key SpaceX test". NASASpaceFlight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2015/05/dragon-2-pad-abort-leap-key-spacex-test/. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ↑ Dragon 2 Propulsive Hover Test. SpaceX. January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (2015-10-21). "SpaceX DragonFly arrives at McGregor for testing". NASASpaceFlight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2015/10/spacex-dragonfly-arrives-mcgregor-testing/. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ↑ "NASA assigns 4 astronauts to commercial Boeing, SpaceX test flights | collectSPACE". http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-070915a-commercial-crew-astronauts.html.

- ↑ Kramer, Miriam (January 27, 2015). "Private Space Taxis on Track to Fly in 2017". Scientific American. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/private-space-taxis-on-track-to-fly-in-2017/. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ "NASA Assigns Crews to First Test Flights, Missions on Commercial Spacecraft". August 3, 2018. https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-assigns-crews-to-first-test-flights-missions-on-commercial-spacecraft.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ZL0tbOZYhE

- ↑ "SpaceX Crew Dragon Hatch Open". NASA Blog. March 3, 2019. https://blogs.nasa.gov/spacestation/2019/03/03/spacex-crew-dragon-hatch-open/.

- ↑ "Crew Demo 1 Mission Overview". March 2019. https://www.spacex.com/sites/spacex/files/crew_demo-1_press_kit.pdf.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aAe0GWIWGI

- ↑ "SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft suffers an anomaly during static fire testing at Cape Canaveral – NASASpaceFlight.com" (in en-US). https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2019/04/spacexs-crew-dragon-spacecraft-anomaly-static-fire-testing/.

- ↑ Bridenstine, Jim. "NASA has been notified about the results of the @SpaceX Static Fire Test and the anomaly that occurred during the final test. We will work closely to ensure we safely move forward with our Commercial Crew Program.". https://twitter.com/JimBridenstine/status/1119754804258062337. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ↑ Mosher, Dave. "SpaceX confirmed that its Crew Dragon spaceship for NASA was 'destroyed' by a recent test. Here's what we learned about the explosive failure.". https://www.businessinsider.com/spacex-crew-dragon-spaceship-test-explosion-2019-5.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Shanklin, Emily (2019-07-15). "UPDATE: IN-FLIGHT ABORT STATIC FIRE TEST ANOMALY INVESTIGATION" (in en). https://www.spacex.com/news/2019/07/15/update-flight-abort-static-fire-anomaly-investigation.

- ↑ "Explosion that destroyed SpaceX Crew Dragon is blamed on leaking valve" (in en-US). https://www.cbsnews.com/news/spacex-explosion-destroyed-crew-dragon-spacecraft-blamed-on-leaking-valve/.

- ↑ "NASA boss says no doubt SpaceX explosion delays flight program". June 18, 2019. https://www.journalpioneer.com/news/world/nasa-boss-says-no-doubt-spacex-explosion-delays-flight-program-323465/.

- ↑ https://spaceflightnow.com/2019/11/13/spacex-fires-up-crew-dragon-thrusters-in-key-test-after-april-explosion/

- ↑ https://www.teslarati.com/spacex-fires-redesigned-crew-dragon-superdraco-flaps/

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (April 10, 2015). "SpaceX conducts tanking test on In-Flight Abort Falcon 9". NASASpaceFlight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2015/04/spacex-tanking-tests-in-flight-abort-falcon-9/. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ↑ Richardson, Derek (30 July 2016). "Second SpaceX Crew Flight Ordered by NASA". Spaceflight Insider. http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/organizations/space-exploration-technologies/second-spacex-crew-flight-ordered-nasa/. "Currently, the first uncrewed test of the spacecraft is expected to launch in May 2017. Sometime after that, SpaceX plans to conduct an in-flight abort to test the SuperDraco thrusters while the rocket is traveling through the area of maximum dynamic pressure – Max Q."

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (February 4, 2016). "SpaceX seeks to accelerate Falcon 9 production and launch rates this year". SpaceNews. http://spacenews.com/spacex-seeks-to-accelerate-falcon-9-production-and-launch-rates-this-year/. Retrieved March 21, 2016. "Shotwell said the company is planning an in-flight abort test of the Crew Dragon spacecraft before the end of this year, where the vehicle uses its thrusters to separate from a Falcon 9 rocket during ascent. That will be followed in 2017 by two demonstration flights to the International Space Station, the first without a crew and the second with astronauts on board, and then the first operational mission."

- ↑ Siceloff, Steven (July 1, 2015). "More Fidelity for SpaceX In-Flight Abort Reduces Risk". http://www.nasa.gov/feature/more-fidelity-for-spacex-in-flight-abort-reduces-risk/. "In the updated plan, SpaceX would launch its uncrewed flight test (DM-1), refurbish the flight test vehicle, then conduct the in-flight abort test prior to the crew flight test. Using the same vehicle for the in-flight abort test will improve the realism of the ascent abort test and reduce risk."

- ↑ https://spaceflightnow.com/2020/01/17/falcon-9-crew-dragon-in-flight-abort-test-mission-status-center/

- ↑ Gebhardt, Chris. "NASA briefly updates status of Crew Dragon anomaly, SpaceX test schedule". https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2019/05/nasa-briefly-crew-dragon-anomaly-spacex-schedule/. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ↑ https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/dragon-v2.htm

- ↑ https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/dragon-v2.htm

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (6 May 2015). "SpaceX crew capsule completes dramatic abort test". http://spaceflightnow.com/2015/05/06/spacex-crew-capsule-completes-dramatic-abort-test/. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ Cooper, Ben (November 2, 2019). "Rocket Launch Viewing Guide for Cape Canaveral". http://www.launchphotography.com/Delta_4_Atlas_5_Falcon_9_Launch_Viewing.html.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "NASA Provides Update on SpaceX Crew Dragon Static Fire Investigation – Commercial Crew Program" (in en-US). https://blogs.nasa.gov/commercialcrew/2019/05/28/nasa-provides-update-on-spacex-crew-dragon-static-fire-investigation/.

- ↑ https://spaceflightnow.com/2020/01/17/falcon-9-crew-dragon-in-flight-abort-test-mission-status-center/

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 "Boeing, SpaceX Secure Additional Crewed Missions Under NASA’s Commercial Space Transport Program – GovCon Wire". https://www.govconwire.com/2017/01/boeing-spacex-secure-additional-crewed-missions-under-nasas-commercial-space-transport-program/.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 "NASA Awards International Space Station Cargo Transport Contracts" (Press release). NASA. January 14, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ↑ Ralph, Eric. "SpaceX’s Crew Dragon gets tentative NASA target for first astronaut launch". https://www.teslarati.com/spacex-crew-dragon-new-astronaut-launch-target/. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ↑ https://www.urdupoint.com/en/technology/russian-space-vehicle-builder-striving-to-lau-482802.html

- ↑ "Rs 10,000 crore plan to send 3 Indians to space by 2022 - Times of India". https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/union-cabinet-clears-rs-10000cr-for-indias-gaganyaan-project/articleshow/67288124.cms.

External links