Physics:History of aerodynamics

Aerodynamics is a branch of dynamics concerned with the study of the motion of air. It is a sub-field of fluid and gas dynamics, and the term "aerodynamics" is often used when referring to fluid dynamics

Early records of fundamental aerodynamic concepts date back to the work of Aristotle and Archimedes in the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC, but efforts to develop a quantitative theory of airflow did not begin until the 18th century. In 1726 Isaac Newton became one of the first aerodynamicists in the modern sense when he developed a theory of air resistance which was later verified for low flow speeds. Air resistance experiments were performed by investigators throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, aided by the construction of the first wind tunnel in 1871. In his 1738 publication Hydrodynamica, Daniel Bernoulli described a fundamental relationship between pressure, velocity, and density, now termed Bernoulli's principle, which provides one method of explaining lift.

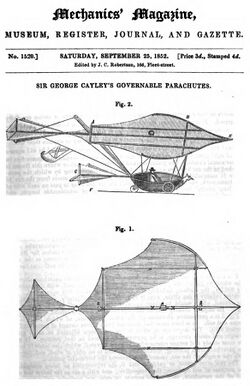

Aerodynamics work throughout the 19th century sought to achieve heavier-than-air flight. George Cayley developed the concept of the modern fixed-wing aircraft in 1799, and in doing so identified the four fundamental forces of flight - lift, thrust, drag, and weight. The development of reasonable predictions of the thrust needed to power flight in conjunction with the development of high-lift, low-drag airfoils paved the way for the first powered flight. On December 17, 1903, Wilbur and Orville Wright flew the first successful powered aircraft. The flight, and the publicity it received, led to more organized collaboration between aviators and aerodynamicists, leading the way to modern aerodynamics.

Theoretical advances in aerodynamics were made parallel to practical ones. The relationship described by Bernoulli was found to be valid only for incompressible, inviscid flow. In 1757, Leonhard Euler published the Euler equations, extending Bernoulli's principle to the compressible flow regime. In the early 19th century, the development of the Navier-Stokes equations extended the Euler equations to account for viscous effects. During the time of the first flights, several investigators developed independent theories connecting flow circulation to lift. Ludwig Prandtl became one of the first people to investigate boundary layers during this time.

Antiquity to the 19th century

Theoretical foundations

Although the modern theory of aerodynamic science did not emerge until the 18th century, its foundations began to emerge in ancient times. The fundamental aerodynamics continuity assumption has its origins in Aristotle's Treatise on the Heavens, although Archimedes, working in the 3rd century BC, was the first person to formally assert that a fluid could be treated as a continuum.[1] Archimedes also introduced the concept that fluid flow was driven by a pressure gradient within the fluid.[2][3] This idea would later prove fundamental to the understanding of fluid flow.

In 1687, Newton's Principia presented Newton's laws of motion, the first complete theoretical approach to understanding mechanical phenomena. In particular, Newton's second law, a statement of the conservation of momentum, is one of three fundamental physical principles used to obtain the Euler equations and Navier-Stokes equations.

In 1738, the Dutch-Switzerland mathematician Daniel Bernoulli published Hydrodynamica, in which he described the fundamental relationship between pressure and velocity, known today as Bernoulli's principle.[4] This states that the pressure of a flowing fluid decreases as its velocity increases and as such was a significant early advance in the theory of fluid dynamics, and was first quantified in an equation derived by Leonhard Euler.[5] This expression, often called Bernoulli's Equation, relates the pressure, density, and velocity at two points along a streamline within a flowing fluid as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {v_1^2 \over 2}+{p_1\over\rho} = {v_2^2 \over 2}+{p_2\over\rho} }[/math]

Bernoulli's Equation ignores compressibility of the fluid, as well as the effects of gravity and viscous forces on the flow. Leonhard Euler would go on to publish the Euler equations in 1757, which are valid for both compressible and incompressible flows. The Euler equations were extended to incorporate the effects of viscosity in the first half of the 1800s, resulting in the Navier-Stokes equations.

Studies of air resistance

The retarding effect of air on a moving object was among the earliest aerodynamic phenomena to be explored. Aristotle wrote about air resistance in the 4th century BC,[3] but lacked the understanding to quantify the resistance he observed. In fact, Aristotle paradoxically suggested that the movement of air around a thrown spear both resisted its motion and propelled it forward.[6] In the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci published the Codex Leicester, in which he rejected Aristotle's theory and attempted to prove that the only effect of air on a thrown object was to resist its motion,[7] and that air resistance was proportional to flow speed, a false conclusion which was supported by Galileo's 17th century observations of pendulum motion decay.[3] In addition to his work on drag, da Vinci was the first person to record a number of aerodynamic ideas including correctly describing the circulation of vortices and the continuity principle as applied to channel flow.[3]

The true quadratic dependency of drag on velocity was experimentally proven independently by Edme Mariotte and Christiaan Huygens, both members of the Paris Academy of Sciences, in the late 17th century.[8] Sir Isaac Newton later became the first person to theoretically derive this quadratic dependence of air resistance in the early 18th century,[9] making him one of the first theoretical aerodynamicists. Newton stated that drag was proportional to the dimensions of a body, the density of the fluid, and the square of the air velocity, a relationship which was demonstrated to be correct for low flow speeds, but stood in direct conflict with Galileo's earlier findings. The discrepancy between the work of Newton, Mariotte, and Huygens, and Galileo's earlier work was not resolved until advances in viscous flow theory in the 20th century.

Newton also developed a law for the drag force on a flat plate inclined towards the direction of the fluid flow. Using F for the drag force, ρ for the density, S for the area of the flat plate, V for the flow velocity, and θ for the angle of attack, his law was expressed as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ F = \rho SV^2 \sin^2 (\theta) }[/math]

This equation overestimates drag in most cases, and was often used in the 19th century to argue the impossibility of human flight.[3] At low inclination angles, drag depends linearly on the sin of the angle, not quadratically. However, Newton's flat plate drag law yields reasonable drag predictions for supersonic flows or very slender plates at large inclination angles which lead to flow separation.[10][11]

Air resistance experiments were carried out by investigators throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Drag theories were developed by Jean le Rond d'Alembert,[12] Gustav Kirchhoff,[13] and Lord Rayleigh.[14] Equations for fluid flow with friction were developed by Claude-Louis Navier[15] and George Gabriel Stokes.[16] To simulate fluid flow, many experiments involved immersing objects in streams of water or simply dropping them off the top of a tall building. Towards the end of this time period Gustave Eiffel used his Eiffel Tower to assist in the drop testing of flat plates.

A more precise way to measure resistance is to place an object within an artificial, uniform stream of air where the velocity is known. The first person to experiment in this fashion was Francis Herbert Wenham, who in doing so constructed the first wind tunnel in 1871. Wenham was also a member of the first professional organization dedicated to aeronautics, the Royal Aeronautical Society of the United Kingdom . Objects placed in wind tunnel models are almost always smaller than in practice, so a method was needed to relate small scale models to their real-life counterparts. This was achieved with the invention of the dimensionless Reynolds number by Osborne Reynolds.[17] Reynolds also experimented with laminar to turbulent flow transition in 1883.

Developments in aviation

Working from at least as early as 1796, when he constructed a model helicopter,[18] until his death in 1857, Sir George Cayley is credited as the first person to identify the four aerodynamic forces of flight—weight, lift, drag, and thrust—and the relationships between them.[19][20] Cayley is also credited as the first person to develop the modern fixed-wing aircraft concept; although da Vinci's notes contain drawings and descriptions of a fixed-wing heavier-than-air flight machine, da Vinci's notes were disorganized and scattered following his death, and his aerodynamics achievements were not rediscovered until after technology had progressed well beyond da Vinci's advances.[21]

By the late 19th century, two problems were identified before heavier-than-air flight could be realized. The first was the creation of low-drag, high-lift aerodynamic wings. The second problem was how to determine the power needed for sustained flight. During this time, the groundwork was laid down for modern day fluid dynamics and aerodynamics, with other less scientifically-inclined enthusiasts testing various flying machines with little success.

In 1884, John J. Montgomery, an American trained in physics, began experimenting with glider designs. Using a water table with circulating water and a smoke chamber he began applying the physics of fluid dynamics to describe the motions of flow over curved surfaces such as airfoils.[22] In 1889, Charles Renard, a French aeronautical engineer, became the first person to reasonably predict the power needed for sustained flight.[23] Renard and German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz explored the wing loading (weight to wing-area ratio) of birds, eventually concluding that humans could not fly under their own power by attaching wings onto their arms. Otto Lilienthal, following the work of Sir George Cayley, was the first person to become highly successful with glider flights. Lilienthal believed that thin, curved airfoils would produce high lift and low drag.

Octave Chanute's 1893 book, Progress in Flying Machines, outlined all of the known research conducted around the world up to that point.[24] Chanute's book provided a great service to those interested in aerodynamics and flying machines.

With the information contained in Chanute's book, the personal assistance of Chanute himself, and research carried out in their own wind tunnel, the Wright brothers gained enough knowledge of aerodynamics to fly the first powered aircraft on December 17, 1903. The Wright brothers' flight confirmed or disproved a number of aerodynamics theories. Newton's drag force theory was finally proved incorrect. This first widely publicised flight led to a more organized effort between aviators and scientists, leading the way to modern aerodynamics.

During the time of the first flights, John J. Montgomery,[25] Frederick W. Lanchester,[26] Martin Kutta, and Nikolai Zhukovsky independently created theories that connected circulation of a fluid flow to lift. Kutta and Zhukovsky went on to develop a two-dimensional wing theory. Expanding upon the work of Lanchester, Ludwig Prandtl is credited with developing the mathematics[27] behind thin-airfoil and lifting-line theories as well as work with boundary layers. Prandtl, a professor at the University of Göttingen, instructed many students who would play important roles in the development of aerodynamics, such as Theodore von Kármán and Max Munk.

Design issues with increasing speed

Compressibility is an important factor in aerodynamics. At low speeds, the compressibility of air is not significant in relation to aircraft design, but as the airflow nears and exceeds the speed of sound, a host of new aerodynamic effects become important in the design of aircraft. These effects, often several of them at a time, made it very difficult for World War II era aircraft to reach speeds much beyond 800 km/h (500 mph).

Some of the minor effects include changes to the airflow that lead to problems in control. For instance, the P-38 Lightning with its thick high-lift wing had a particular problem in high-speed dives that led to a nose-down condition. Pilots would enter dives, and then find that they could no longer control the plane, which continued to nose over until it crashed. The problem was remedied by adding a "dive flap" beneath the wing which altered the center of pressure distribution so that the wing would not lose its lift.[28]

A similar problem affected some models of the Supermarine Spitfire. At high speeds, the ailerons could apply more torque than the Spitfire's thin wings could handle, and the entire wing would twist in the opposite direction. This meant that the plane would roll in the direction opposite to that which the pilot intended, and led to a number of accidents. Earlier models weren't fast enough for this to be a problem, and so it wasn't noticed until later model Spitfires like the Mk.IX started to appear. This was mitigated by adding considerable torsional rigidity to the wings, and was wholly cured when the Mk.XIV was introduced.

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Mitsubishi Zero had the exact opposite problem in which the controls became ineffective. At higher speeds, the pilot simply couldn't move the controls because there was too much airflow over the control surfaces. The planes would become difficult to maneuver, and at high enough speeds aircraft without this problem could out-turn them.

These problems were eventually solved as jet aircraft reached transonic and supersonic speeds. German scientists in WWII experimented with swept wings. Their research was applied on the MiG-15 and F-86 Sabre and bombers such as the B-47 Stratojet used swept wings which delay the onset of shock waves and reduce drag.

In order to maintain control near and above the speed of sound, it is often necessary to use either power-operated all-flying tailplanes (stabilators), or delta wings fitted with power-operated elevons. Power operation prevents aerodynamic forces overriding the pilots' control inputs.

Finally, another common problem that fits into this category is flutter. At some speeds, the airflow over the control surfaces will become turbulent, and the controls will start to flutter. If the speed of the fluttering is close to a harmonic of the control's movement, the resonance could break the control off completely. This was a serious problem on the Zero and VL Myrsky. When problems with poor control at high speed were first encountered, they were addressed by designing a new style of control surface with more power. However, this introduced a new resonant mode, and a number of planes were lost before this was discovered. On design of VL Myrsky, this problem was countered by increasing the rigidity and weight of the wing, therefore increasing the dampening of the harmonic oscillation, which compromised the performance to some extent.

All of these effects are often mentioned in conjunction with the term "compressibility", but in a manner of speaking, they are incorrectly used. From a strictly aerodynamic point of view, the term should refer only to those side-effects arising as a result of the changes in airflow from an incompressible fluid (similar in effect to water) to a compressible fluid (acting as a gas) as the speed of sound is approached. There are two effects in particular, wave drag and Critical Mach number.

Wave drag is a sudden rise in drag on the aircraft, caused by air building up in front of it. At lower speeds, this air has time to "get out of the way", guided by the air in front of it that is in contact with the aircraft. But at the speed of sound, this can no longer happen, and the air which was previously following the streamline around the aircraft now hits it directly. The amount of power needed to overcome this effect is considerable. The critical Mach number is the speed at which some of the air passing over the aircraft's wing becomes supersonic.

At the speed of sound, the way that lift is generated changes dramatically, from being dominated by Bernoulli's principle to forces generated by shock waves. Since the air on the top of the wing is traveling faster than on the bottom, due to Bernoulli effect, at speeds close to the speed of sound the air on the top of the wing will be accelerated to supersonic. When this happens, the distribution of lift changes dramatically, typically causing a powerful nose-down trim. Since the aircraft normally approached these speeds only in a dive, pilots would report the aircraft attempting to nose over into the ground.

Dissociation absorbs a great deal of energy in a reversible process. This greatly reduces the thermodynamic temperature of hypersonic gas decelerated near an aerospace vehicle. In transition regions, where this pressure dependent dissociation is incomplete, both the differential, constant pressure heat capacity and beta (the volume/pressure differential ratio) will greatly increase. The latter has a pronounced effect on vehicle aerodynamics including stability.

Faster than sound – later 20th century

As aircraft began to travel faster, aerodynamicists realized that the density of air began to change as it came into contact with an object, leading to a division of fluid flow into the incompressible and compressible regimes. In compressible aerodynamics, density and pressure both change, which is the basis for calculating the speed of sound. Newton was the first to develop a mathematical model for calculating the speed of sound, but it was not correct until Pierre-Simon Laplace accounted for the molecular behavior of gases and introduced the heat capacity ratio. The ratio of the flow speed to the speed of sound was named the Mach number after Ernst Mach, who was one of the first to investigate the properties of supersonic flow which included Schlieren photography techniques to visualize the changes in density. Macquorn Rankine and Pierre Henri Hugoniot independently developed the theory for flow properties before and after a shock wave. Jakob Ackeret led the initial work on calculating the lift and drag on a supersonic airfoil.[29] Theodore von Kármán and Hugh Latimer Dryden introduced the term transonic to describe flow speeds around Mach 1 where drag increases rapidly. Because of the increase in drag approaching Mach 1, aerodynamicists and aviators disagreed on whether supersonic flight was achievable.

On September 30, 1935, an exclusive conference was held in Rome with the topic of high velocity flight and the possibility of breaking the sound barrier.[30] Participants included Theodore von Kármán, Ludwig Prandtl, Jakob Ackeret, Eastman Jacobs, Adolf Busemann, Geoffrey Ingram Taylor, Gaetano Arturo Crocco, and Enrico Pistolesi. Ackeret presented a design for a supersonic wind tunnel. Busemann gave a presentation on the need for aircraft with swept wings for high speed flight. Eastman Jacobs, working for NACA, presented his optimized airfoils for high subsonic speeds which led to some of the high performance American aircraft during World War II. Supersonic propulsion was also discussed. The sound barrier was broken using the Bell X-1 aircraft twelve years later, thanks in part to those individuals.

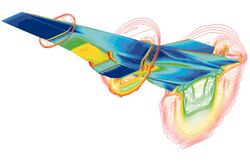

By the time the sound barrier was broken, much of the subsonic and low supersonic aerodynamics knowledge had matured. The Cold War fueled an ever-evolving line of high performance aircraft. Computational fluid dynamics was started as an effort to solve for flow properties around complex objects and has rapidly grown to the point where entire aircraft can be designed using a computer, with wind-tunnel tests followed by flight tests to confirm the computer predictions.

With some exceptions, the knowledge of hypersonic aerodynamics has matured between the 1960s and the present decade. Therefore, the goals of an aerodynamicist have shifted from understanding the behavior of fluid flow to understanding how to engineer a vehicle to interact appropriately with the fluid flow. For example, while the behavior of hypersonic flow is understood, building a scramjet aircraft to fly at hypersonic speeds has seen very limited success. Along with building a successful scramjet aircraft, the desire to improve the aerodynamic efficiency of current aircraft and propulsion systems will continue to fuel new research in aerodynamics. Nevertheless, there are still important problems in basic aerodynamic theory, such as in predicting transition to turbulence, and the existence and uniqueness of solutions to the Navier-Stokes equations.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Anderson 1997, p. 17.

- ↑ Anderson 1997, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Ackroyd, J. A. D.; Axcell, B. P.; Ruban, A. I. (2001). Early Developments of Modern Aerodynamics. Reston, Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. ISBN 1-56347-516-2.

- ↑ "Hydrodynamica". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/658890/Hydrodynamica#tab=active~checked%2Citems~checked&title=Hydrodynamica%20--%20Britannica%20Online%20Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Anderson 1997, p. 47.

- ↑ Anderson 1997, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Anderson 1997, p. 25.

- ↑ Anderson 1997, pp. 32-35.

- ↑ Newton, I. (1726). Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Book II.

- ↑ von Karman, Theodore (2004). Aerodynamics: Selected Topics in the Light of Their Historical Development. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43485-0. OCLC 53900531.

- ↑ Anderson 1997, p. 40.

- ↑ d'Alembert, J. (1752). Essai d'une nouvelle theorie de la resistance des fluides.

- ↑ Kirchhoff, G. (1869). Zur Theorie freier Flussigkeitsstrahlen. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (70), 289-298.

- ↑ Rayleigh, Lord (1876). On the Resistance of Fluids. Philosophical Magazine (5)2, 430-441.

- ↑ Navier, C. L. M. H. (1827). "Memoire sur les lois du mouvement des fluides". Mémoires de l'Académie des Sciences 6: 389–440.

- ↑ Stokes, G. (1845). On the Theories of the Internal Friction of Fluids in Motion. Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society (8), 287-305.

- ↑ Reynolds, O. (1883). An Experimental Investigation of the Circumstances which Determine whether the Motion of Water Shall Be Direct or Sinuous and of the Law of Resistance in Parallel Channels. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A-174, 935-982. https://archive.org/details/philtrans06508925.

- ↑ Wragg, D.W.; Flight before flying, Osprey, 1974, Page 57.

- ↑ "U.S Centennial of Flight Commission - Sir George Cayley.". http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Prehistory/Cayley/PH2.htm. "Sir George Cayley, born in 1773, is sometimes called the Father of Aviation. A pioneer in his field, he was the first to identify the four aerodynamic forces of flight - weight, lift, drag, and thrust and their relationship. He was also the first to build a successful human-carrying glider. Cayley described many of the concepts and elements of the modern airplane and was the first to understand and explain in engineering terms the concepts of lift and thrust."

- ↑ Anderson 1997, pp. 21, 25-26.

- ↑ Harwood, CS and Fogel, GB Quest for Flight: John J. Montgomery and the Dawn of Aviation in the West, University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

- ↑ Renard, C. (1889). Nouvelles experiences sur la resistance de l'air. L'Aeronaute (22) 73-81.

- ↑ Chanute, Octave (1997). Progress in Flying Machines. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-29981-3. OCLC 37782926.

- ↑ Harwood, CS and Fogel, GB Quest for Flight: John J. Montgomery and the Dawn of Aviation in the West University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

- ↑ Lanchester, F. W. (1907). Aerodynamics. https://archive.org/details/aerodynamicscons00lanc.

- ↑ Prandtl, L. (1919). Tragflügeltheorie. Göttinger Nachrichten, mathematischphysikalische Klasse, 451-477.

- ↑ Bodie, Warren M. (2 May 2001). The Lockheed P-38 Lightning. pp. 174–175. ISBN 0-9629359-5-6.

- ↑ Ackeret, J. (1925). Luftkrafte auf Flugel, die mit der grosserer als Schallgeschwindigkeit bewegt werden. Zeitschrift fur Flugtechnik und Motorluftschiffahrt (16), 72-74.

- ↑ Anderson, John D. (2007). Fundamentals of Aerodynamics (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-125408-3. OCLC 60589123.

References

- Anderson, John David (1997). A History of Aerodynamics and its Impact on Flying machines. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45435-2.

|