Biography:Gustav Kirchhoff

Gustav Kirchhoff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Gustav Robert Kirchhoff 12 March 1824 Königsberg, East Prussia, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died | 17 October 1887 (aged 63) |

| Resting place | Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof, Berlin |

| Alma mater | University of Königsberg (Dr. phil.) |

| Known for | |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 5 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Thermodynamics, electromagnetism, graph theory, optics, spectroscopy |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Ueber den Durchgang eines elektrischen Stromes durch eine Ebene, insbesondere durch eine kreisförmige (1847) |

| Doctoral advisor | Franz Ernst Neumann |

| Notable students | See list

|

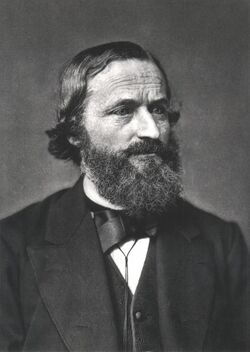

Gustav Robert Kirchhoff (de; 12 March 1824 – 17 October 1887) was a German physicist and mathematician who contributed to the fundamental understanding of electrical circuits, spectroscopy, and the emission of black-body radiation by heated objects.[3][4] He coined the term black body in 1860.[5]

Several different sets of concepts are named "Kirchhoff's laws" after him, which include Kirchhoff's circuit laws, Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation, Kirchhoff's diffraction formula, and Kirchhoff's law of thermochemistry.

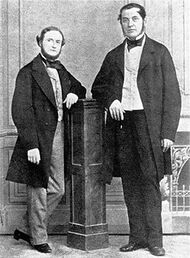

The Bunsen–Kirchhoff Award for spectroscopy is named after Kirchhoff and his colleague, Robert Bunsen.

Biography

Gustav Robert Kirchhoff was born on 12 March 1824 in Königsberg, Prussia, the son of Friedrich Kirchhoff, a lawyer, and Johanna Henriette Wittke.[6] His family were Lutherans in the Evangelical Church of Prussia.

Kirchhoff studied at the University of Königsberg, where he attended the mathematico-physical seminar directed by C. G. J. Jacobi,[7] Franz Ernst Neumann, and Friedrich Julius Richelot. In 1845, while a student, Kirchhoff formulated two circuit laws—which are now ubiquitous in electrical engineering. He completed this study as a seminar exercise; it later became his doctoral thesis, supervised by Neumann.

In 1847, Kirchhoff graduated from the University of Königsberg and became a Privatdozent (unsalaried lecturer) at the University of Berlin, where he stayed until 1850 when he was offered a professorship at the University of Breslau. In 1854, he was called to the University of Heidelberg, where he collaborated with Robert Bunsen in spectroscopic work. In 1875, Kirchhoff returned to Berlin, where he remained until his death in 1887.

In 1857, Kirchhoff married Clara Richelot, the daughter of his mathematics professor Richelot; the couple had five children. In 1872, after Clara's death in 1869, he married Luise Brömmel.[8]

In 1864, Kirchhoff was elected a Member of the American Philosophical Society.[9] In 1884, he became a Foreign Member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[10]

Kirchhoff died on 17 October 1887 in Berlin at the age of 63. He is buried at Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof (Old St. Matthew's Cemetery) in Schöneberg, Berlin (just a few meters from the graves of the Brothers Grimm).

Research

In 1857, Kirchhoff calculated that an electric signal in a resistanceless wire travels along the wire at the speed of light.[11][12]

In 1859, Kirchhoff proposed a law of thermal radiation, and gave a proof in 1861.

Together, Kirchhoff and Bunsen improved on Joseph von Fraunhofer's 1814 spectroscope, which Kirchhoff used to pioneer the identification of the elements in the Sun, showing in 1859 that the Sun contains sodium. Kirchhoff and Bunsen discovered caesium and rubidium in 1861.[13]

Kirchhoff contributed greatly to the field of spectroscopy by formalizing three laws that describe the spectral composition of light emitted by incandescent objects, building substantially on the discoveries of David Alter and Anders Jonas Ångström. In 1862, he was awarded the Rumford Medal "for his researches on the fixed lines of the solar spectrum, and on the inversion of the bright lines in the spectra of artificial light".[lower-alpha 1]

Kirchhoff also contributed to optics, carefully solving the wave equation to provide a solid foundation for Huygens' principle (and correct it in the process).[15][16]

Kirchhoff's circuit laws

Kirchhoff's first law At any node in an electrical circuit where current can branch, the sum of the currents leaving the node is equal to the sum of the currents entering the node. The second law is that the algebraic sum of the potential drops along a closed circuit, taken in any direction of flow, is equal to zero.[17]

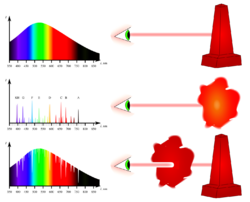

Kirchhoff's three laws of spectroscopy

- A solid, liquid, or dense gas excited to emit light will radiate at all wavelengths and thus produce a continuous spectrum.

- A low-density gas excited to emit light will do so at specific wavelengths, and this produces an emission spectrum.

- If light composing a continuous spectrum passes through a cool, low-density gas, the result will be an absorption spectrum.

Kirchhoff did not know about the existence of energy levels in atoms. The existence of discrete spectral lines had been known since Fraunhofer discovered them in 1814. That the lines formed a discrete mathematical pattern was described by Johann Balmer in 1885. Joseph Larmor explained the splitting of the spectral lines in a magnetic field known as the Zeeman Effect by the oscillation of electrons.[18][19] These discrete spectral lines were not explained as electron transitions until the Bohr model of the atom in 1913, which helped lead to quantum mechanics.

Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation

It was Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation in which he proposed an unknown universal law for radiation that led Max Planck to the discovery of the quantum of action leading to quantum mechanics.

Kirchhoff's law of thermochemistry

Kirchhoff showed in 1858 that, in thermochemistry, the variation of the heat of a chemical reaction is given by the difference in heat capacity between products and reactants:

- .

Integration of this equation permits the evaluation of the heat of reaction at one temperature from measurements at another temperature.[20][21]

Kirchhoff's theorem in graph theory

Kirchhoff also worked in the mathematical field of graph theory, in which he proved Kirchhoff's matrix tree theorem.

Works

- (in de) Gesammelte Abhandlungen. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth. 1882. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=11943571.

- (in de) Vorlesungen über Electricität und Magnetismus. Leipzig: Benedictus Gotthelf Teubner. 1891. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=11946679.

- Vorlesungen über mathematische Physik. 4 vols., B. G. Teubner, Leipzig 1876–1894.

- Vol. 1: Mechanik. 1. Auflage, B. G. Teubner, Leipzig 1876 (online).

- Vol. 2: Mathematische Optik. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig 1891 (Herausgegeben von Kurt Hensel, online).

- Vol. 3: Electricität und Magnetismus. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig 1891 (Herausgegeben von Max Planck, online).

- Vol. 4: Theorie der Wärme. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig 1894, Herausgegeben von Max Planck[22]

See also

- Circuit rank

- Computational aeroacoustics

- Flame emission spectroscopy

- Spectroscope

- Kirchhoff Institute of Physics

- List of German inventors and discoverers

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 "Gustav Kirchhoff - The Mathematics Genealogy Project". https://www.genealogy.math.ndsu.nodak.edu/id.php?id=46968.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 "Gustav Robert Kirchhoff - Physics Tree". https://academictree.org/physics/peopleinfo.php?pid=25612.

- ↑ Marshall, James L.; Marshall, Virginia R. (2008). "Rediscovery of the Elements: Mineral Waters and Spectroscopy". The Hexagon: 42–48. http://www.chem.unt.edu/~jimm/REDISCOVERY%207-09-2018/Hexagon%20Articles/bunsen%20and%20spectroscopy.pdf. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ↑ Waygood, Adrian (19 June 2013) (in en). An Introduction to Electrical Science. Routledge. ISBN 9781135071134. https://books.google.com/books?id=8qHGRTC7h-MC&pg=PT79.

- ↑ Schmitz, Kenneth S. (2018). Physical Chemistry. Elsevier. pp. 278. ISBN 9780128005996.

- ↑ Kondepudi, Dilip; Prigogine, Ilya (5 November 2014) (in en). Modern Thermodynamics: From Heat Engines to Dissipative Structures. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 288. ISBN 9781118698709. https://books.google.com/books?id=SPU8BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA288.

- ↑ Hockey, Thomas (2009). "Kirchhoff, Gustav Robert". The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. http://www.springerreference.com/docs/html/chapterdbid/58778.html. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "Gustav Robert Kirchhoff – Dauerausstellung". Kirchhoff-Institute for Physics. http://www.kip.uni-heidelberg.de/oeffwiss/kirchhoff. "Am 16. August 1857 heiratete er Clara Richelot, die Tochter des Königsberger Mathematikers ... Frau Clara starb schon 1869. Im Dezember 1872 heiratete Kirchhoff Luise Brömmel."

- ↑ "APS Member History". https://search.amphilsoc.org/memhist/search?creator=&title=&subject=&subdiv=&mem=&year=1864&year-max=1864&dead=&keyword=&smode=advanced.

- ↑ "G. R. Kirchhoff (1824–1887)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. http://www.dwc.knaw.nl/biografie/pmknaw/?pagetype=authorDetail&aId=PE00001261.

- ↑ Kirchhoff, Gustav (1857). "On the motion of electricity in wires". Philosophical Magazine 13: 393–412.

- ↑ Graneau, Peter; Assis, André Koch Torres (1994). "Kirchhoff on the motion of electricity in conductors". Apeiron 1 (19): 19–25. http://www.ifi.unicamp.br/~assis/Apeiron-V19-p19-25%281994%29.pdf.

- ↑ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1956). The discovery of the elements (6th ed.). Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education. https://archive.org/details/discoveryoftheel002045mbp.

- ↑ Asimov, Isaac, The Secret of the Universe, Oxford University Press, 1992, p. 109

- ↑ Baker, Bevan B.; and Copson, Edward T.; The Mathematical Theory of Huygens' Principle, Oxford University Press, 1939, pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Miller, David A. B.; "Huygens's wave propagation principle corrected", Optics Letters 16, 1370–1372, 1991

- ↑ Corso di Fisicia 2 author Paul A .Tipler

- ↑ Buchwald, Jed Z.; and Warwick, Andrew; editors; Histories of the Electron: The Birth of Microphysics

- ↑ Larmor, Joseph (1897), "On a Dynamical Theory of the Electric and Luminiferous Medium, Part 3, Relations with material media", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 190: 205–300, doi:10.1098/rsta.1897.0020, Bibcode: 1897RSPTA.190..205L

- ↑ Laidler, Keith J.; and Meiser, J. H.; "Physical Chemistry", Benjamin/Cummings 1982, p. 62

- ↑ Atkins, Peter; and de Paula, J.; "Atkins' Physical Chemistry", W. H. Freeman, 2006 (8th edition), p. 56

- ↑ Merritt, Ernest (1895). "Review of Vorlesungen über mathematische Physik. Vol. IV. Theorie der Wärme by Gustav Kirchhoff, edited by Max Planck". Physical Review (American Physical Society): 73–75. https://books.google.com/books?id=wx7OAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA73.

Bibliography

- Warburg, E. (1925). "Zur Erinnerung an Gustav Kirchhoff". Die Naturwissenschaften 13 (11): 205. doi:10.1007/BF01558883. Bibcode: 1925NW.....13..205W.

- Stepanov, B. I. (1977). "Gustav Robert Kirchhoff (on the ninetieth anniversary of his death)". Journal of Applied Spectroscopy 27 (3): 1099. doi:10.1007/BF00625887. Bibcode: 1977JApSp..27.1099S.

- Everest, A. S. (1969). "Kirchhoff-Gustav Robert 1824–1887". Physics Education 4 (6): 341. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/4/6/304. Bibcode: 1969PhyEd...4..341E.

- Kirchhoff, Gustav (1860). "Ueber die Fraunhoferschen Linien". Monatsberichte der Königliche Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin: 662–665. ISBN 978-1-113-39933-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=XDIXZiXWIuEC&pg=PA3. HathiTrust full text. Partial English translation available in Magie, William Francis, A Source Book in Physics (1963). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 354-360.

- Kirchhoff, Gustav (1860). “IV. Ueber das Verhältniß zwischen dem Emissionsvermögen und dem Absorptionsvermögen der Körper für Wärme und Licht,” Annalen der Physik 185(2), 275–301. (coinage of term “blackbody”) [On the relationship between the emissivity and the absorptivity of bodies for heat and light]

Further reading

- Gustav Kirchhoff at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Gustav Kirchhoff", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Kirchhoff.html.

- Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang, ed. "Kirchhoff, Gustav (1824–1887)". http://scienceworld.wolfram.com/biography/Kirchhoff.html.

- Klaus Hentschel: Gustav Robert Kirchhoff und seine Zusammenarbeit mit Robert Wilhelm Bunsen, in: Karl von Meyenn (Hrsg.) Die Grossen Physiker, Munich: Beck, vol. 1 (1997), pp. 416–430, 475–477, 532–534.

- Klaus Hentschel: Mapping the Spectrum. Techniques of Visual Representation in Research and Teaching, Oxford: OUP, 2002.

- Kirchhoff's 1857 paper on the speed of electrical signals in a wire

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Kirchhoff, Gustav Robert". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Kirchhoff, Gustav Robert". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Kirchhoff, Gustav Robert". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Sketch of Gustav Robert Kirchhoff". Popular Science Monthly 33. May 1888.

- "Kirchhoff, Gustav Robert". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

External links

|