Physics:Hypersonic speed

In aerodynamics, hypersonic speed refers to speeds much faster than the speed of sound, usually more than approximately Mach 5.[1][2][3]

The precise Mach number at which a craft can be said to be flying at hypersonic speed varies, since individual physical changes in the airflow (like molecular dissociation and ionization) occur at different speeds; these effects collectively become important around Mach 5–10. The hypersonic regime can also be alternatively defined as speeds where specific heat capacity changes with the temperature of the flow as the kinetic energy of the moving object is converted into heat.[4]

Hypersonic weapons are typically boost-glide vehicles or cruise missiles designed for aerodynamic flight and maneuvering above Mach 5.

High hypersonic speeds are experienced during atmospheric entry. Spaceplanes are designed to be capable of flight in this regime. The North American X-15 and the Space Shuttle orbiter are the only crewed vehicles to fly above Mach 5.

Characteristics of flow

While the definition of hypersonic flow can be quite vague [1][lower-alpha 1] a hypersonic flow may be characterized by certain physical phenomena at very fast supersonic flow.[5]

- Shock layer [1]

- Shock interaction - aerothermal:[6] aerodynamic heating[1] of the fuselage [7]

- Entropy layer

- Real gas effects

- Low density effects

- Independence of aerodynamic coefficients with Mach number.

Small shock stand-off distance

As a body's Mach number increases, the density behind a bow shock generated by the body also increases, which corresponds to a decrease in volume behind the shock due to conservation of mass. Consequently, the distance between the bow shock and the body decreases at higher Mach numbers.[8]

Entropy layer

As Mach numbers increase, the entropy change across the shock also increases, which results in a strong entropy gradient and highly vortical flow that mixes with the boundary layer.

Viscous interaction

High-temperature flow

Classification of Mach regimes

Although "subsonic" and "supersonic" usually refer to speeds below and above the local speed of sound respectively, aerodynamicists often use these terms to refer to particular ranges of Mach values. When an aircraft approaches transonic speeds (around Mach 1), it enters a special regime. The usual approximations based on the Navier–Stokes equations, which work well for subsonic designs, start to break down because, even in the freestream, some parts of the flow locally exceed Mach 1. So, more sophisticated methods are needed to handle this complex behavior.[9]

| Regime | Mach No | Speed | General characteristics | Aircraft | Missiles/warheads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsonic | < 1 [1] | <614 mph (988 km/h; 274 m/s) | Most often propeller-driven and commercial turbofan aircraft with high-aspect-ratio (slender) wings, and rounded features like the nose and leading edges.

The subsonic speed range is that range of speeds within which, all of the airflow over an aircraft is less than Mach 1. The critical Mach number (Mcrit) is lowest free stream Mach number at which airflow over any part of the aircraft first reaches Mach 1. So the subsonic speed range includes all speeds that are less than Mcrit. |

All commercial aircraft | — |

| Transonic | 0.8–1.2 | 614–921 mph (988–1,482 km/h; 274–412 m/s) | Transonic aircraft nearly always have swept wings that delay drag-divergence and supercritical wings to delay the onset of wave drag and often feature designs adhering to the principles of the Whitcomb area rule. |

|

— |

| Supersonic | > 1 [1] | 921–3,836 mph (1,482–6,173 km/h; 412–1,715 m/s) | The supersonic speed range is that range of speeds within which all of the airflow over an aircraft is supersonic (more than Mach 1). But airflow meeting the leading edges is initially decelerated, so the free stream speed must be slightly greater than Mach 1 to ensure that all of the flow over the aircraft is supersonic. It is commonly accepted that the supersonic speed range starts at a free stream speed greater than Mach 1.3.

Aircraft designed to fly at supersonic speeds show large differences in their aerodynamic design because of the radical differences in the behavior of flows above Mach 1. Sharp edges, thin aerofoil-sections, and all-moving tailplane/canards are common. Modern combat aircraft must compromise in order to maintain low-speed handling; "true" supersonic designs, generally incorporating delta wings, are rarer. |

|

— |

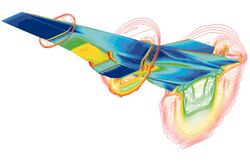

| Hypersonic | > 5 [1] | 3,836–7,673 mph (6,173–12,348 km/h; 1,715–3,430 m/s) | Cooled nickel or titanium skin; small wings. The design is highly integrated, instead of assembled from separate independently-designed components, due to the domination of interference effects, where small changes in any one component will cause large changes in air flow around all other components, which in turn affects their behavior. The result is that no one component can be designed without knowing how all other components will affect all of the air flows around the craft, and any changes to any one component may require a redesign of all other components simultaneously . |

|

| |

| High-Hypersonic | [10–25) | 7,673–19,180 mph (12,348–30,867 km/h; 3,430–8,574 m/s) | Thermal control becomes a dominant design consideration. Structure must either be designed to operate hot, or be protected by special silicate tiles or similar. Chemically reacting flow can also cause corrosion of the vehicle's skin, with free-atomic oxygen featuring in very high-speed flows. Hypersonic designs are often forced into blunt configurations because of the aerodynamic heating rising with a reduced radius of curvature. | — | |

| Re-entry speeds | ≥25 | ≥19,180 mph (30,870 km/h; 8,570 m/s) | Ablative heat shield; small or no wings; blunt shape. See reentry capsule. |

|

|

Similarity parameters

Hypersonic flows, however, require other similarity parameters. First, the analytic equations for the oblique shock angle become nearly independent of Mach number at high (~>10) Mach numbers. Second, the formation of strong shocks around aerodynamic bodies means that the freestream Reynolds number is less useful as an estimate of the behavior of the boundary layer over a body (although it is still important). Finally, the increased temperature of hypersonic flow mean that real gas effects become important. Research in hypersonics is therefore often called aerothermodynamics, rather than aerodynamics.[10]

Wallace D. Hayes developed a similarity parameter, similar to the Whitcomb area rule, which allowed similar configurations to be compared. In the study of hypersonic flow over slender bodies, the product of the freestream Mach number and the flow deflection angle , known as the hypersonic similarity parameter:is considered to be an important governing parameter.[10] The slenderness ratio of a vehicle , where is the diameter and is the length, is often substituted for .

Regimes

Perfect gas

Two-temperature ideal gas

Dissociated gas

Ionized gas

Radiation-dominated regime

- Optically thin: where the gas does not re-absorb radiation emitted from other parts of the gas

- Optically thick: where the radiation must be considered a separate source of energy.

The modeling of optically thick gases is extremely difficult, since, due to the calculation of the radiation at each point, the computation load theoretically expands exponentially as the number of points considered increases.

See also

- Hypersonic glide vehicle

- Supersonic transport

- Lifting body

- Atmospheric entry

- Hypersonic flight

- DARPA Falcon Project

- Reaction Engines Skylon (design study)

- Reaction Engines A2 (design study)

- HyperSoar (concept)

- Boeing X-51 Waverider

- X-20 Dyna-Soar (cancelled)

- Rockwell X-30 (cancelled)

- Avatar RLV (2001 Indian concept study)

- Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle (Indian project)

- Ayaks (Russian wave rider project from the 1990s)

- Avangard (Russian hypersonic glide vehicle, in service)

- DF-ZF (Chinese hypersonic glide vehicle, operational)

- Lockheed Martin SR-72 (planned)

- WZ-8 Chinese Hypersonic surveillance UAV (In Service)

- MD-22 Chinese Hypersonic Unmanned combat aerial vehicle (In development)

- Engines

- Rocket engine

- Ramjet

- Scramjet

- Reaction Engines SABRE, LAPCAT (design studies)

- Missiles

- 3M22 Zircon Anti-ship hypersonic cruise missile

(in production)

(in production) - BrahMos-II Cruise Missile –

(Under Development)

(Under Development)

- Other flow regimes

Notes

- ↑ is generally debatable (especially because of the absence of discontinuity between supersonic and hypersonic flows)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Leishman, J. Gordon (January 2023). 53 Hypersonic Flight Vehicles. Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. https://eaglepubs.erau.edu/introductiontoaerospaceflightvehicles/chapter/hypersonic-flight-vehicles/. Retrieved 28 June 2025. "Hypersonic flow is typically considered to begin around Mach 5, but this threshold is not sharply defined" - "Sonic Booms in Hypersonic Flight.".

- ↑ Galison, P., ed (2000). "The Changing Nature of Flight and Ground Test Instrumentation and Data: 1940-1969". Atmospheric Flight in the Twentieth Century. Springer. p. 90. ISBN 978-94-011-4379-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=qfrOBgAAQBAJ&q=hypersonic.

- ↑ https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/engineering/hypersonic-speed

- ↑ "Specific Heat Capacity, Calorically Imperfect Gas". NASA. https://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/BGH/realspec.html.

- ↑ GÜlçat, Ülgen (2021). "Hypersonic Flow". Fundamentals of Modern Unsteady Aerodynamics (3 ed.). Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-60777-7. ISBN 978-3-030-60777-7. Bibcode: 2021fmua.book.....G. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-60777-7_7. Retrieved 6 July 2025.

- ↑ Fengshou Xiao; Zhufei Li; Yujian Zhu; Jiming Yang (19 October 2016). "Hypersonic Type-IV Shock/Shock Interactions on a Blunt Body with Forward-Facing Cavity". Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics) 54 (2): 506–512. doi:10.2514/1.A33556. https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/full/10.2514/1.A33556. Retrieved 10 July 2025.

- ↑ J. Urzay (July 2020). "The physical characteristics of hypersonic flows". Center for Turbulence Research. p. 3. https://web.stanford.edu/~jurzay/hypersonicsCh2_Urzay.pdf.

- ↑ Shang, J. S. (2001-01-01). "Recent research in magneto-aerodynamics". Progress in Aerospace Sciences 37 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1016/S0376-0421(00)00015-4. ISSN 0376-0421. Bibcode: 2001PrAeS..37....1S. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376042100000154.

- ↑ "Hypersonics". doi:10.1007/978-3-030-60777-7_6. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-60777-7_6.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Anderson, Jr., John D. (2006). Hypersonic and High-Temperature Gas Dynamics. AIAA Education Series (2nd ed.). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. ISBN 1-56347-780-7.

External links

- NASA's Guide to Hypersonics

- Hypersonics Group at Imperial College

- University of Queensland Centre for Hypersonics

- High Speed Flow Group at University of New South Wales

- Hypersonics Group at the University of Oxford

|