Physics:Heat sink

A heat sink (also commonly spelled heatsink[1]) is a passive heat exchanger that transfers the heat generated by an electronic or a mechanical device to a fluid medium, often air or a liquid coolant, where it is dissipated away from the device, thereby allowing regulation of the device's temperature. In computers, heat sinks are used to cool CPUs, GPUs, and some chipsets and RAM modules. Heat sinks are used with high-power semiconductor devices such as power transistors and optoelectronics such as lasers and light-emitting diodes (LEDs), where the heat dissipation ability of the component itself is insufficient to moderate its temperature.

A heat sink is designed to maximize its surface area in contact with the cooling medium surrounding it, such as the air. Air velocity, choice of material, protrusion design and surface treatment are factors that affect the performance of a heat sink. Heat sink attachment methods and thermal interface materials also affect the die temperature of the integrated circuit. Thermal adhesive or thermal paste improve the heat sink's performance by filling air gaps between the heat sink and the heat spreader on the device. A heat sink is usually made out of aluminium or copper.

Heat transfer principle

A heat sink transfers thermal energy from a higher-temperature device to a lower-temperature fluid medium. The fluid medium is frequently air, but can also be water, refrigerants or oil. If the fluid medium is water, the heat sink is frequently called a cold plate. In thermodynamics a heat sink is a heat reservoir that can absorb an arbitrary amount of heat without significantly changing temperature. Practical heat sinks for electronic devices must have a temperature higher than the surroundings to transfer heat by convection, radiation, and conduction. The power supplies of electronics are not absolutely efficient, so extra heat is produced that may be detrimental to the function of the device. As such, a heat sink is included in the design to disperse heat.

Fourier's law of heat conduction shows that when there is a temperature gradient in a body, heat will be transferred from the higher-temperature region to the lower-temperature region. The rate at which heat is transferred by conduction, [math]\displaystyle{ q_k }[/math], is proportional to the product of the temperature gradient and the cross-sectional area through which heat is transferred. When it is simplified to a one-dimensional form in the x direction, it can be expressed as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ q_k = -k A \frac{dT}{dx}. }[/math]

For a heat sink in a duct, where air flows through the duct, the heat-sink base will usually be hotter than the air flowing through the duct. Applying the conservation of energy, for steady-state conditions, and Newton's law of cooling to the temperature nodes shown in the diagram gives the following set of equations:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{Q} = \dot{m} c_{p,\text{in}}(T_\text{air,out} - T_\text{air,in}), }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{Q} = \frac{T_\text{hs} - T_\text{air,av}}{R_\text{hs}}, }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ T_\text{air,av} = \frac{T_\text{air,in} + T_\text{air,out}}{2}. }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{m} }[/math] is the air mass flow rate in kg/s

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_{p,\text{in}} }[/math] is the specific heat capacity of the incoming air, in J/(kg °C)

- [math]\displaystyle{ {R_\text{hs}} }[/math] is the thermal resistance of the heatsink

Using the mean air temperature is an assumption that is valid for relatively short heat sinks. When compact heat exchangers are calculated, the logarithmic mean air temperature is used.

The above equations show that:

- When the air flow through the heat sink decreases, this results in an increase in the average air temperature. This in turn increases the heat-sink base temperature. And additionally, the thermal resistance of the heat sink will also increase. The net result is a higher heat-sink base temperature.

- The increase in heat-sink thermal resistance with decrease in flow rate will be shown later in this article.

- The inlet air temperature relates strongly with the heat-sink base temperature. For example, if there is recirculation of air in a product, the inlet air temperature is not the ambient air temperature. The inlet air temperature of the heat sink is therefore higher, which also results in a higher heat-sink base temperature.

- If there is no air flow around the heat sink, energy cannot be transferred.

- A heat sink is not a device with the "magical ability to absorb heat like a sponge and send it off to a parallel universe".[2]

Natural convection requires free flow of air over the heat sink. If fins are not aligned vertically, or if fins are too close together to allow sufficient air flow between them, the efficiency of the heat sink will decline.

Design factors

Thermal resistance

For semiconductor devices used in a variety of consumer and industrial electronics, the idea of thermal resistance simplifies the selection of heat sinks. The heat flow between the semiconductor die and ambient air is modeled as a series of resistances to heat flow; there is a resistance from the die to the device case, from the case to the heat sink, and from the heat sink to the ambient air. The sum of these resistances is the total thermal resistance from the die to the ambient air. Thermal resistance is defined as temperature rise per unit of power, analogous to electrical resistance, and is expressed in units of degrees Celsius per watt (°C/W). If the device dissipation in watts is known, and the total thermal resistance is calculated, the temperature rise of the die over the ambient air can be calculated.

The idea of thermal resistance of a semiconductor heat sink is an approximation. It does not take into account non-uniform distribution of heat over a device or heat sink. It only models a system in thermal equilibrium and does not take into account the change in temperatures with time. Nor does it reflect the non-linearity of radiation and convection with respect to temperature rise. However, manufacturers tabulate typical values of thermal resistance for heat sinks and semiconductor devices, which allows selection of commercially manufactured heat sinks to be simplified.[3]

Commercial extruded aluminium heat sinks have a thermal resistance (heat sink to ambient air) ranging from 0.4 °C/W for a large sink meant for TO-3 devices, up to as high as 85 °C/W for a clip-on heat sink for a TO-92 small plastic case.[3] The popular 2N3055 power transistor in a TO-3 case has an internal thermal resistance from junction to case of 1.52 °C/W.[4] The contact between the device case and heat sink may have a thermal resistance between 0.5 and 1.7 °C/W, depending on the case size and use of grease or insulating mica washer.[3]

Material

The materials for heat sink applications should have high heat capacity and thermal conductivity in order to absorb more heat energy without shifting towards a very high temperature and transmit it to the environment for efficient cooling.[5] The most common heat sink materials are aluminium alloys.[6] Aluminium alloy 1050 has one of the higher thermal conductivity values at 229 W/(m·K) and heat capacity of 922 J/(kg·K),[7] but is mechanically soft. Aluminium alloys 6060 (low-stress), 6061, and 6063 are commonly used, with thermal conductivity values of 166 and 201 W/(m·K) respectively. The values depend on the temper of the alloy. One-piece aluminium heat sinks can be made by extrusion, casting, skiving or milling.

Copper has excellent heat-sink properties in terms of its thermal conductivity, corrosion resistance, biofouling resistance, and antimicrobial resistance (see also Copper in heat exchangers). Copper has around twice the thermal conductivity of aluminium, around 400 W/(m·K) for pure copper. Its main applications are in industrial facilities, power plants, solar thermal water systems, HVAC systems, gas water heaters, forced air heating and cooling systems, geothermal heating and cooling, and electronic systems.

Copper is three times as dense[6] and more expensive than aluminium, and copper is less ductile than aluminum.[6] One-piece copper heat sinks can be made by skiving or milling. Sheet-metal fins can be soldered onto a rectangular copper body.[8][9]

Fin efficiency

Fin efficiency is one of the parameters that makes a higher-thermal-conductivity material important. A fin of a heat sink may be considered to be a flat plate with heat flowing in one end and being dissipated into the surrounding fluid as it travels to the other.[10] As heat flows through the fin, the combination of the thermal resistance of the heat sink impeding the flow and the heat lost due to convection, the temperature of the fin and, therefore, the heat transfer to the fluid, will decrease from the base to the end of the fin. Fin efficiency is defined as the actual heat transferred by the fin, divided by the heat transfer were the fin to be isothermal (hypothetically the fin having infinite thermal conductivity). These equations are applicable for straight fins:[11]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \eta_\text{f} = \frac{\tanh(mL_c)}{mL_c}, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ mL_c = \sqrt{\frac{2h_\text{f}}{kt_\text{f}}} L_\text{f}, }[/math]

where

- hf is the convection coefficient of the fin:

- 10 to 100 W/(m2·K) in air,

- 500 to 10,000 W/(m2·K) in water,

- k is the thermal conductivity of the fin material:

- Lf is the fin height (m),

- tf is the fin thickness (m).

Fin efficiency is increased by decreasing the fin aspect ratio (making them thicker or shorter), or by using a more conductive material (copper instead of aluminium, for example).

Spreading resistance

Another parameter that concerns the thermal conductivity of the heat-sink material is spreading resistance. Spreading resistance occurs when thermal energy is transferred from a small area to a larger area in a substance with finite thermal conductivity. In a heat sink, this means that heat does not distribute uniformly through the heat-sink base. The spreading resistance phenomenon is shown by how the heat travels from the heat source location and causes a large temperature gradient between the heat source and the edges of the heat sink. This means that some fins are at a lower temperature than if the heat source were uniform across the base of the heat sink. This nonuniformity increases the heat sink's effective thermal resistance.

To decrease the spreading resistance in the base of a heat sink:

- increase the base thickness,

- choose a different material with higher thermal conductivity,

- use a vapor chamber or heat pipe in the heat sink base.

Fin arrangements

A pin fin heat sink is a heat sink that has pins that extend from its base. The pins can be cylindrical, elliptical, or square. A second type of heat sink fin arrangement is the straight fin. A variation on the straight fin heat sink is a cross-cut heat sink. A third type of heat sink is the flared fin heat sink, where the fins are not parallel to one another. Flaring the fins decreases flow resistance and makes more air go through the heat-sink fin channel; otherwise, more air would bypass the fins. Slanting them keeps the overall dimensions the same, but offers longer fins. Examples of the three types are shown in the image on the right.

Forghan, et al.[12] have published data on tests conducted on pin fin, straight fin, and flared fin heat sinks. They found that for low air approach velocity, typically around 1 m/s, the thermal performance is at least 20% better than straight fin heat sinks. Lasance and Eggink[13] also found that for the bypass configurations that they tested, the flared heat sink performed better than the other heat sinks tested.

Generally, the more surface area a heat sink has, the better its performance.[2] Real-world performance depends on the design and application. The concept of a pin fin heat sink is to pack as much surface area into a given volume as possible, while working in any orientation of fluid flow.[2] Kordyban[2] has compared the performance of a pin-fin and a straight-fin heat sink of similar dimensions. Although the pin-fin has 194 cm2 surface area while the straight-fin has 58 cm2, the temperature difference between the heat-sink base and the ambient air for the pin fin is 50 °C, but for the straight-fin it was 44 °C, or 6 °C better than the pin fin. Pin fin heat sink performance is significantly better than straight fins when used in their optimal application where the fluid flows axially along the pins rather than only tangentially across the pins.

| Heat-sink fin type | Width [cm] | Length [cm] | Height [cm] | Surface area [cm2] | Volume [cm3] | Temperature difference, Tcase − Tair [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Straight | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 58 | 20 | 44 |

| Pin | 3.8 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 194 | 24 | 51 |

Cavities (inverted fins)

Cavities (inverted fins) embedded in a heat source are the regions formed between adjacent fins that stand for the essential promoters of nucleate boiling or condensation. These cavities are usually utilized to extract heat from a variety of heat-generating bodies to a heat sink.[14][15]

Conductive thick plate between the heat source and the heat sink

Placing a conductive thick plate as a heat-transfer interface between a heat source and a cold flowing fluid (or any other heat sink) may improve the cooling performance. In such arrangement, the heat source is cooled under the thick plate instead of being cooled in direct contact with the cooling fluid. It is shown[citation needed] that the thick plate can significantly improve the heat transfer between the heat source and the cooling fluid by conducting the heat current in an optimal manner. The two most attractive advantages of this method are that no additional pumping power and no extra heat-transfer surface area, that is quite different from fins (extended surfaces).

Surface color

The heat transfer from the heat sink occurs by convection of the surrounding air, conduction through the air, and radiation.

Heat transfer by radiation is a function of both the heat-sink temperature and the temperature of the surroundings that the heat sink is optically coupled with. When both of these temperatures are on the order of 0 °C to 100 °C, the contribution of radiation compared to convection is generally small, and this factor is often neglected. In this case, finned heat sinks operating in either natural-convection or forced-flow will not be affected significantly by surface emissivity.

In situations where convection is low, such as a flat non-finned panel with low airflow, radiative cooling can be a significant factor. Here the surface properties may be an important design factor. Matte-black surfaces radiate much more efficiently than shiny bare metal.[16][17] A shiny metal surface has low emissivity. The emissivity of a material is tremendously frequency-dependent and is related to absorptivity (of which shiny metal surfaces have very little). For most materials, the emissivity in the visible spectrum is similar to the emissivity in the infrared spectrum;[citation needed] however, there are exceptions – notably, certain metal oxides that are used as "selective surfaces".

In vacuum or outer space, there is no convective heat transfer, thus in these environments, radiation is the only factor governing heat flow between the heat sink and the environment. For a satellite in space, a 100 °C (373 K) surface facing the Sun will absorb a lot of radiant heat, because the Sun's surface temperature is nearly 6000 K, whereas the same surface facing deep space will radiate a lot of heat, since deep space has an effective temperature of only several Kelvin.

Engineering applications

Microprocessor cooling

Heat dissipation is an unavoidable by-product of electronic devices and circuits.[10] In general, the temperature of the device or component will depend on the thermal resistance from the component to the environment, and the heat dissipated by the component. To ensure that the component does not overheat, a thermal engineer seeks to find an efficient heat transfer path from the device to the environment. The heat transfer path may be from the component to a printed circuit board (PCB), to a heat sink, to air flow provided by a fan, but in all instances, eventually to the environment.

Two additional design factors also influence the thermal/mechanical performance of the thermal design:

- The method by which the heat sink is mounted on a component or processor. This will be discussed under the section attachment methods.

- For each interface between two objects in contact with each other, there will be a temperature drop across the interface. For such composite systems, the temperature drop across the interface may be appreciable.[11] This temperature change may be attributed to what is known as the thermal contact resistance.[11] Thermal interface materials (TIM) decrease the thermal contact resistance.

Attachment methods

As power dissipation of components increases and component package size decreases, thermal engineers must innovate to ensure components won't overheat. Devices that run cooler last longer. A heat sink design must fulfill both its thermal as well as its mechanical requirements. Concerning the latter, the component must remain in thermal contact with its heat sink with reasonable shock and vibration. The heat sink could be the copper foil of a circuit board, or a separate heat sink mounted onto the component or circuit board. Attachment methods include thermally conductive tape or epoxy, wire-form z clips, flat spring clips, standoff spacers, and push pins with ends that expand after installing.

- Thermally conductive tape

Thermally conductive tape is one of the most cost-effective heat sink attachment materials.[18] It is suitable for low-mass heat sinks and for components with low power dissipation. It consists of a thermally conductive carrier material with a pressure-sensitive adhesive on each side.

This tape is applied to the base of the heat sink, which is then attached to the component. Following are factors that influence the performance of thermal tape:[18]

- Surfaces of both the component and heat sink must be clean, with no residue such as a film of silicone grease.

- Preload pressure is essential to ensure good contact. Insufficient pressure results in areas of non-contact with trapped air, and results in higher-than-expected interface thermal resistance.

- Thicker tapes tend to provide better "wettability" with uneven component surfaces. "Wettability" is the percentage area of contact of a tape on a component. Thicker tapes, however, have a higher thermal resistance than thinner tapes. From a design standpoint, it is best to strike a balance by selecting a tape thickness that provides maximum "wettability" with minimum thermal resistance.

- Epoxy

Epoxy is more expensive than tape, but provides a greater mechanical bond between the heat sink and component, as well as improved thermal conductivity.[18] The epoxy chosen must be formulated for this purpose. Most epoxies are two-part liquid formulations that must be thoroughly mixed before being applied to the heat sink, and before the heat sink is placed on the component. The epoxy is then cured for a specified time, which can vary from 2 hours to 48 hours. Faster cure time can be achieved at higher temperatures. The surfaces to which the epoxy is applied must be clean and free of any residue.

The epoxy bond between the heat sink and component is semi-permanent/permanent.[18] This makes re-work very difficult and at times impossible. The most typical damage caused by rework is the separation of the component die heat spreader from its package.

- Wire form Z-clips

More expensive than tape and epoxy, wire form z-clips attach heat sinks mechanically. To use the z-clips, the printed circuit board must have anchors. Anchors can be either soldered onto the board, or pushed through. Either type requires holes to be designed into the board. The use of RoHS solder must be allowed for because such solder is mechanically weaker than traditional Pb/Sn solder.

To assemble with a z-clip, attach one side of it to one of the anchors. Deflect the spring until the other side of the clip can be placed in the other anchor. The deflection develops a spring load on the component, which maintains very good contact. In addition to the mechanical attachment that the z-clip provides, it also permits using higher-performance thermal interface materials, such as phase change types.[18]

- Clips

Available for processors and ball grid array (BGA) components, clips allow the attachment of a BGA heat sink directly to the component. The clips make use of the gap created by the ball grid array (BGA) between the component underside and PCB top surface. The clips therefore require no holes in the PCB. They also allow for easy rework of components.

- Push pins with compression springs

For larger heat sinks and higher preloads, push pins with compression springs are very effective.[18] The push pins, typically made of brass or plastic, have a flexible barb at the end that engages with a hole in the PCB; once installed, the barb retains the pin. The compression spring holds the assembly together and maintains contact between the heat sink and component. Care is needed in selection of push pin size. Too great an insertion force can result in the die cracking and consequent component failure.

- Threaded standoffs with compression springs

For very large heat sinks, there is no substitute for the threaded standoff and compression spring attachment method.[18] A threaded standoff is essentially a hollow metal tube with internal threads. One end is secured with a screw through a hole in the PCB. The other end accepts a screw which compresses the spring, completing the assembly. A typical heat sink assembly uses two to four standoffs, which tends to make this the most costly heat sink attachment design. Another disadvantage is the need for holes in the PCB.

| Method | Pros | Cons | Cost |

| Thermal tape | Easy to attach. Inexpensive. | Cannot provide mechanical attachment for heavier heat sinks or for high vibration environments. Surface must be cleaned for optimal adhesion. Moderate to low thermal conductivity. | Very low |

| Epoxy | Strong mechanical adhesion. Relatively inexpensive. | Makes board rework difficult since it can damage component. Surface must be cleaned for optimal adhesion. | Very low |

| Wire form Z-clips | Strong mechanical attachment. Easy removal/rework. Applies a preload to the thermal interface material, improving thermal performance. | Requires holes in the board or solder anchors. More expensive than tape or epoxy. Custom designs. | Low |

| Clip-on | Applies a preload to the thermal interface material, improving thermal performance. Requires no holes or anchors. Easy removal/rework. | Must have "keep out" zone around the BGA for the clip. Extra assembly steps. | Low |

| Push pin with compression springs | Strong mechanical attachment. Highest thermal interface material preload. Easy removal and installation. | Requires holes in the board which increases complexity of traces in PCB. | Moderate |

| Stand-offs with compression springs | Strongest mechanical attachment. Highest preload for the thermal interface material. Ideal for large heat sinks. | Requires holes in the board which increases complexity of trace layout. Complicated assembly. | High |

Thermal interface materials

Thermal contact resistance occurs due to the voids created by surface roughness effects, defects and misalignment of the interface. The voids present in the interface are filled with air. Heat transfer is therefore due to conduction across the actual contact area and to conduction (or natural convection) and radiation across the gaps.[11] If the contact area is small, as it is for rough surfaces, the major contribution to the resistance is made by the gaps.[11] To decrease the thermal contact resistance, the surface roughness can be decreased while the interface pressure is increased. However, these improving methods are not always practical or possible for electronic equipment. Thermal interface materials (TIM) are a common way to overcome these limitations.

Properly applied thermal interface materials displace the air that is present in the gaps between the two objects with a material that has a much-higher thermal conductivity. Air has a thermal conductivity of 0.022 W/(m·K)[19] while TIMs have conductivities of 0.3 W/(m·K)[20] and higher.

When selecting a TIM, care must be taken with the values supplied by the manufacturer. Most manufacturers give a value for the thermal conductivity of a material. However, the thermal conductivity does not take into account the interface resistances. Therefore, if a TIM has a high thermal conductivity, it does not necessarily mean that the interface resistance will be low.

Selection of a TIM is based on three parameters: the interface gap which the TIM must fill, the contact pressure, and the electrical resistivity of the TIM. The contact pressure is the pressure applied to the interface between the two materials. The selection does not include the cost of the material. Electrical resistivity may be important depending upon electrical design details.

| Interface gap values | Products types available | |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.05 mm | < 2 mil | Thermal grease, epoxy, phase change materials |

| 0.05–0.1 mm | 2–5 mil | Phase change materials, polyimide, graphite or aluminium tapes |

| 0.1–0,5 mm | 5–18 mil | Silicone-coated fabrics |

| > 0.5 mm | > 18 mil | Gap fillers |

| Contact pressure scale | Typical pressure ranges | Product types available |

|---|---|---|

| Very low | < 70 kPa | Gap fillers |

| Low | < 140 kPa | Thermal grease, epoxy, polyimide, graphite or aluminium tapes |

| High | 2 MPa | Silicone-coated fabrics |

| Electrical insulation | Dielectric strength | Typical values | Product types available | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not required | N/A | N/A | N/A | Thermal grease, epoxy, phase-change materials, graphite, or aluminium tapes. |

| Required | Low | 10 kV/mm | < 300 V/mil | Silicone coated fabrics, gap fillers |

| Required | High | 60 kV/mm | > 1500 V/mil | Polyimide tape |

| Product type | Application notes | Thermal performance |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal paste | Messy. Labor-intensive. Relatively long assembly time. | ++++ |

| Epoxy | Creates "permanent" interface bond. | ++++ |

| Phase change | Allows for pre-attachment. Softens and conforms to interface defects at operational temperatures. Can be repositioned in field. | ++++ |

| Thermal tapes, including graphite, polyimide, and aluminium tapes | Easy to apply. Some mechanical strength. | +++ |

| Silicone coated fabrics | Provide cushioning and sealing while still allowing heat transfer. | + |

| Gap filler | Can be used to thermally couple differing-height components to a heat spreader or heat sink. Naturally tacky. | ++ |

Light-emitting diode lamps

Light-emitting diode (LED) performance and lifetime are strong functions of their temperature.[21] Effective cooling is therefore essential. A case study of a LED based downlighter shows an example of the calculations done in order to calculate the required heat sink necessary for the effective cooling of lighting system.[22] The article also shows that in order to get confidence in the results, multiple independent solutions are required that give similar results. Specifically, results of the experimental, numerical and theoretical methods should all be within 10% of each other to give high confidence in the results.

In soldering

Temporary heat sinks are sometimes used while soldering circuit boards, preventing excessive heat from damaging sensitive nearby electronics. In the simplest case, this means partially gripping a component using a heavy metal crocodile clip, hemostat, or similar clamp. Modern semiconductor devices, which are designed to be assembled by reflow soldering, can usually tolerate soldering temperatures without damage. On the other hand, electrical components such as magnetic reed switches can malfunction if exposed to hotter soldering irons, so this practice is still very much in use.[23]

Methods to determine performance

In general, a heat sink performance is a function of material thermal conductivity, dimensions, fin type, heat transfer coefficient, air flow rate, and duct size. To determine the thermal performance of a heat sink, a theoretical model can be made. Alternatively, the thermal performance can be measured experimentally. Due to the complex nature of the highly 3D flow in present applications, numerical methods or computational fluid dynamics (CFD) can also be used. This section will discuss the aforementioned methods for the determination of the heat sink thermal performance.

A heat transfer theoretical model

One of the methods to determine the performance of a heat sink is to use heat transfer and fluid dynamics theory. One such method has been published by Jeggels, et al.,[24] though this work is limited to ducted flow. Ducted flow is where the air is forced to flow through a channel which fits tightly over the heat sink. This makes sure that all the air goes through the channels formed by the fins of the heat sink. When the air flow is not ducted, a certain percentage of air flow will bypass the heat sink. Flow bypass was found to increase with increasing fin density and clearance, while remaining relatively insensitive to inlet duct velocity.[25]

The heat sink thermal resistance model consists of two resistances, namely the resistance in the heat sink base, [math]\displaystyle{ R_{b} }[/math], and the resistance in the fins, [math]\displaystyle{ R_{f} }[/math]. The heat sink base thermal resistance, [math]\displaystyle{ R_{b} }[/math], can be written as follows if the source is a uniformly applied the heat sink base. If it is not, then the base resistance is primarily spreading resistance:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_b = \frac{t_b}{kA_b} }[/math] (4)

where [math]\displaystyle{ t_b }[/math] is the heat sink base thickness, [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] is the heat sink material thermal conductivity and [math]\displaystyle{ A_b }[/math] is the area of the heat sink base.

The thermal resistance from the base of the fins to the air, [math]\displaystyle{ R_{f} }[/math], can be calculated by the following formulas:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_f = \frac{1}{n h_f W_f \left ( t_f + 2\eta_f L_f \right)} }[/math] (5)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \eta_f = \frac{\tanh{mL_c}}{mL_c} }[/math][11] (6)

- [math]\displaystyle{ mL_c = \sqrt{\frac{2h_f}{k t_f}}L_f }[/math][11] (7)

- [math]\displaystyle{ D_h = \frac{4A_{ch}}{P_{ch}} }[/math] (8)

- [math]\displaystyle{ Re = \frac{4 \dot{G} \rho}{n \pi D_h \mu} }[/math] (9)

- [math]\displaystyle{ f = (0.79 \ln Re - 1.64)^{-2} }[/math][26] (10)

- [math]\displaystyle{ Nu = \frac{(f/8)(Re - 1000)Pr}{1+12.7(f/8)^{0.5}(Pr^{\frac{2}{3}}-1)} }[/math][26] (11)

- [math]\displaystyle{ h_f = \frac{Nu k_{air}}{D_h} }[/math] (12)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho = \frac{P_{atm}}{R_aT_{in}} }[/math] (13)

The flow rate can be determined by the intersection of the heat sink system curve and the fan curve. The heat sink system curve can be calculated by the flow resistance of the channels and inlet and outlet losses as done in standard fluid mechanics text books, such as Potter, et al.[27] and White.[28]

Once the heat sink base and fin resistances are known, then the heat sink thermal resistance, [math]\displaystyle{ R_{hs} }[/math] can be calculated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_{hs}=R_{b} + R_{f} }[/math] (14).

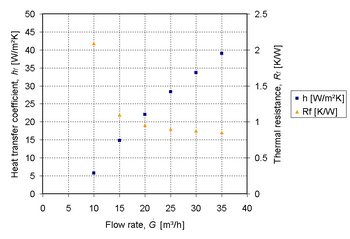

Using the equations 5 to 13 and the dimensional data in,[24] the thermal resistance for the fins was calculated for various air flow rates. The data for the thermal resistance and heat transfer coefficient are shown in the diagram, which shows that for an increasing air flow rate, the thermal resistance of the heat sink decreases.

Experimental methods

Experimental tests are one of the more popular ways to determine the heat sink thermal performance. In order to determine the heat sink thermal resistance, the flow rate, input power, inlet air temperature and heat sink base temperature need to be known. Vendor-supplied data is commonly provided for ducted test results.[29] However, the results are optimistic and can give misleading data when heat sinks are used in an unducted application. More details on heat sink testing methods and common oversights can be found in Azar, et al.[29]

Numerical methods

In industry, thermal analyses are often ignored in the design process or performed too late — when design changes are limited and become too costly.[10] Of the three methods mentioned in this article, theoretical and numerical methods can be used to determine an estimate of the heat sink or component temperatures of products before a physical model has been made. A theoretical model is normally used as a first order estimate. Online heat sink calculators[30] can provide a reasonable estimate of forced and natural convection heat sink performance based on a combination of theoretical and empirically derived correlations. Numerical methods or computational fluid dynamics (CFD) provide a qualitative (and sometimes even quantitative) prediction of fluid flows.[31][32] What this means is that it will give a visual or post-processed result of a simulation, like the images in figures 16 and 17, and the CFD animations in figure 18 and 19, but the quantitative or absolute accuracy of the result is sensitive to the inclusion and accuracy of the appropriate parameters.

CFD can give an insight into flow patterns that are difficult, expensive or impossible to study using experimental methods.[31] Experiments can give a quantitative description of flow phenomena using measurements for one quantity at a time, at a limited number of points and time instances. If a full-scale model is not available or not practical, scale models or dummy models can be used. The experiments can have a limited range of problems and operating conditions. Simulations can give a prediction of flow phenomena using CFD software for all desired quantities, with high resolution in space and time and virtually any problem and realistic operating conditions. However, if critical, the results may need to be validated.[2]

Pin fin heat sink with thermal profile and free convection flow trajectories predicted using a CFD analysis package |

|

See also

- Computer cooling

- Heat spreader

- Heat pipe

- Heat pump

- Thermal conductivity of diamond

- Radiator

- Thermal interface material

- Thermal management (electronics)

- Thermal resistance

- Thermoelectric cooling

References

- ↑ "Heatsink". 3 November 2020. https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/heatsink.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Kordyban, T. (1998). Hot Air Rises and Heat Sinks: Everything you know about cooling electronics is wrong. ASME Press. ISBN 978-0-7918-0074-4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Nello Sevastopoulos et al., National Semiconductor Voltage Regulator Handbook, National Semiconductor Corp., 1975, chapters 4, 5, 6.

- ↑ Type 2N3055 N-P-N Single Diffused Mesa Silicon Power Transistor data sheet, Texas Instruments, bulletin number DL-S-719659, August 1967, revised December 1971.

- ↑ Khan, Junaid; Momin, Syed Abdul; Mariatti, M. (30 October 2020). "A review on advanced carbon-based thermal interface materials for electronic devices". Carbon 168: 65–112. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2020.06.012.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Anon, Unknown, "Heat sink selection". , Mechanical engineering department, San Jose State University [27 January 2010].

- ↑ "Aluminium Matter Organization UK". http://aluminium.matter.org.uk/aluselect/default.asp.

- ↑ "Copper heatsinks". http://www.cooliance.com/resources/copper-heatsinks.html.

- ↑ "Heatsink Design and Selection: Material". http://www.abl-heatsinks.co.uk/heatsink/heatsink-selection-material.htm.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Sergent, J.; Krum, A. (1998). Thermal management handbook for electronic assemblies (First ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Incropera, F.P. and DeWitt, D.P., 1985, Introduction to heat transfer, John Wiley and sons, NY.

- ↑ Forghan, F., Goldthwaite, D., Ulinski, M., Metghalchi, M., 2001, Experimental and Theoretical Investigation of Thermal Performance of Heat Sinks, ISME May.

- ↑ Lasance, C. J. M. and Eggink, H. J., 2001, A Method to Rank Heat Sinks in Practice: The Heat Sink Performance Tester, 21st IEEE SEMI-THERM Symposium.

- ↑ Biserni, C.; Rocha, L. A. O.; Bejan, A. (2004). "Inverted fins: Geometric optimization of the intrusion into a conducting wall". International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 47 (12–13): 2577–2586. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2003.12.018.

- ↑ Lorenzini, G.; Biserni, C.; Rocha, L. A. O. (2011). "Geometric optimization of isothermal cavities according to Bejan's theory". International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 54 (17–18): 3868–3873. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2011.04.042.

- ↑ Mornhinweg, Manfred. "Thermal design". http://ludens.cl/Electron/Thermal.html.

- ↑ "Effects of Anodization on Radiational Heat Transfer – heat sinks". http://www.aavid.com/product-group/extrusions-na/anodize.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Azar, K, et al., 2008, "Thermally Conductive Tapes", can-dotape.com, accessed on 3/21/2013

- ↑ Lienard, J. H. IV & V (2004). A Heat Transfer Textbook (Third ed.). MIT.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Saint-Gobain (2004). Thermal management solutions for electronic equipment. http://www.fff.saint-gobain.com/Media/Documents/S0000000000000001036/ThermaCool%20Brochure.pdf. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ↑ Bider, C. (2009). "Effect of thermal environment on LED light emission and lifetime". LED Professional Review May/June 2009. http://www.led-professional.com/downloads/LpR_13_468932.pdf.

- ↑ Azar, K. (September 2009). "LED lighting: A case study in thermal management". Qpedia Thermal E-Magazine. http://www.qats.com/cpanel/UploadedPdf/Qpedia_0909_web.pdf.

- ↑ James Johnston, "Reed Switches", Electronics in Meccano, Issue 6, January 2000.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Jeggels, Y. U.; Dobson, R. T.; Jeggels, D. H. (2007). Comparison of the cooling performance between heat pipe and aluminium conductors for electronic equipment enclosures.

- ↑ Prstic, S.; Iyengar, M.; Bar-Cohen, A. (2000). "Bypass effect in high performance heat sinks". Proceedings of the International Thermal Science Seminar Bled, Slovenia, June 11 – 14.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Mills, A.F., 1999, Heat transfer, Second edition, Prentice Hall.

- ↑ Potter, C. M.; Wiggert, D. C. (2002). Mechanics of fluid (Third ed.). Brooks/Cole.

- ↑ White, F. M. (1999). Fluid mechanics (Fourth ed.). McGraw-Hill International.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Azar, A. (January 2009). "Heat sink testing methods and common oversights". Qpedia Thermal E-Magazine. http://www.qats.com/cpanel/UploadedPdf/January20092.pdf.

- ↑ "Heat Sink Calculator: Online Heat Sink Analysis and Design". http://heatsinkcalculator.com.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Kuzmin, D., Unknown, "Course: Introduction to CFD", Dortmund University of Technology.

- ↑ Kim, Seo Young; Koo, Jae-Mo; Kuznetsov, Andrey V. (2001). "Effect of anisotropy in permeability and effective thermal conductivity on thermal performance of an aluminum foam heat sink". Numerical Heat Transfer Part A: Applications 40 (1): 21–36. doi:10.1080/104077801300348851. Bibcode: 2001NHTA...40...21K.

External links

pt:Dissipador

|