Physics:Density of air

The density of air or atmospheric density, denoted ρ, is the mass per unit volume of Earth's atmosphere. Air density, like air pressure, decreases with increasing altitude. It also changes with variations in atmospheric pressure, temperature and humidity. At 101.325 kPa (abs) and 20 °C (68 °F), air has a density of approximately 1.204 kg/m3 (0.0752 lb/cu ft), according to the International Standard Atmosphere (ISA). At 101.325 kPa (abs) and 15 °C (59 °F), air has a density of approximately 1.225 kg/m3 (0.0765 lb/cu ft), which is about 1⁄800 that of water, according to the International Standard Atmosphere (ISA).[citation needed] Pure liquid water is 1,000 kg/m3 (62 lb/cu ft).

Air density is a property used in many branches of science, engineering, and industry, including aeronautics;[1][2][3] gravimetric analysis;[4] the air-conditioning[5] industry; atmospheric research and meteorology;[6][7][8] agricultural engineering (modeling and tracking of Soil-Vegetation-Atmosphere-Transfer (SVAT) models);[9][10][11] and the engineering community that deals with compressed air.[12]

Depending on the measuring instruments used, different sets of equations for the calculation of the density of air can be applied. Air is a mixture of gases and the calculations always simplify, to a greater or lesser extent, the properties of the mixture.

Temperature

Other things being equal, hotter air is less dense than cooler air and will thus rise through cooler air. This can be seen by using the ideal gas law as an approximation.

Dry air

The density of dry air can be calculated using the ideal gas law, expressed as a function of temperature and pressure:[citation needed] [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \rho &= \frac{p}{R_\text{specific} T}\\ R_\text{specific} &= \frac{R}{M} = \frac{k_{\rm B}}{m}\\ \rho &= \frac{pM}{RT} = \frac{pm}{k_{\rm B}T}\\ \end{align} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math], air density (kg/m3)[note 1]

- [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], absolute pressure (Pa)[note 1]

- [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math], absolute temperature (K)[note 1]

- [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] is the gas constant, 8.31446261815324 in J⋅K−1⋅mol−1 [note 1]

- [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is the molar mass of dry air, approximately 0.0289652 in kg⋅mol−1.[note 1]

- [math]\displaystyle{ k_{\rm B} }[/math] is the Boltzmann constant, 1.380649×10−23 in J⋅K−1[note 1]

- [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is the molecular mass of dry air, approximately 4.81×10−26 in kg.[note 1]

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_\text{specific} }[/math], the specific gas constant for dry air, which using the values presented above would be approximately 287.0500676 in J⋅kg−1⋅K−1[note 1].

Therefore:

- At IUPAC standard temperature and pressure (0 °C and 100 kPa), dry air has a density of approximately 1.2754 kg/m3.[citation needed]

The following table illustrates the air density–temperature relationship at 1 atm or 101.325 kPa:[citation needed]

| Temperature T (°C) |

Speed of sound c (m/s) |

Density of air ρ (kg/m3) |

Characteristic specific acoustic impedance z0 (Pa·s/m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 351.88 | 1.1455 | 403.2 |

| 30 | 349.02 | 1.1644 | 406.5 |

| 25 | 346.13 | 1.1839 | 409.4 |

| 20 | 343.21 | 1.2041 | 413.3 |

| 15 | 340.27 | 1.2250 | 416.9 |

| 10 | 337.31 | 1.2466 | 420.5 |

| 5 | 334.32 | 1.2690 | 424.3 |

| 0 | 331.30 | 1.2922 | 428.0 |

| −5 | 328.25 | 1.3163 | 432.1 |

| −10 | 325.18 | 1.3413 | 436.1 |

| −15 | 322.07 | 1.3673 | 440.3 |

| −20 | 318.94 | 1.3943 | 444.6 |

| −25 | 315.77 | 1.4224 | 449.1 |

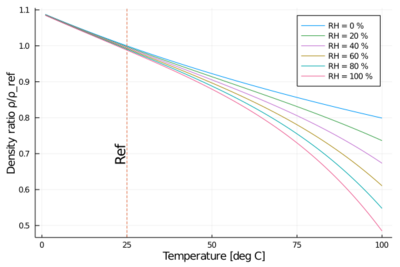

Humid air

The addition of water vapor to air (making the air humid) reduces the density of the air, which may at first appear counter-intuitive. This occurs because the molar mass of water vapor (18 g/mol) is less than the molar mass of dry air[note 2] (around 29 g/mol). For any ideal gas, at a given temperature and pressure, the number of molecules is constant for a particular volume (see Avogadro's Law). So when water molecules (water vapor) are added to a given volume of air, the dry air molecules must decrease by the same number, to keep the pressure or temperature from increasing. Hence the mass per unit volume of the gas (its density) decreases.

The density of humid air may be calculated by treating it as a mixture of ideal gases. In this case, the partial pressure of water vapor is known as the vapor pressure. Using this method, error in the density calculation is less than 0.2% in the range of −10 °C to 50 °C. The density of humid air is found by:[13] [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_\text{humid air} = \frac{p_\text{d}}{R_\text{d} T} + \frac{p_\text{v}}{R_\text{v} T} = \frac{p_\text{d}M_\text{d} + p_\text{v}M_\text{v}}{R T} }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_\text{humid air} }[/math], density of the humid air (kg/m3)

- [math]\displaystyle{ p_\text{d} }[/math], partial pressure of dry air (Pa)

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_\text{d} }[/math], specific gas constant for dry air, 287.058 J/(kg·K)

- [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math], temperature (K)

- [math]\displaystyle{ p_\text{v} }[/math], pressure of water vapor (Pa)

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_\text{v} }[/math], specific gas constant for water vapor, 461.495 J/(kg·K)

- [math]\displaystyle{ M_\text{d} }[/math], molar mass of dry air, 0.0289652 kg/mol

- [math]\displaystyle{ M_\text{v} }[/math], molar mass of water vapor, 0.018016 kg/mol

- [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math], universal gas constant, 8.31446 J/(K·mol)

The vapor pressure of water may be calculated from the saturation vapor pressure and relative humidity. It is found by: [math]\displaystyle{ p_\text{v} = \phi p_\text{sat} }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ p_\text{v} }[/math], vapor pressure of water

- [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math], relative humidity (0.0–1.0)

- [math]\displaystyle{ p_\text{sat} }[/math], saturation vapor pressure

The saturation vapor pressure of water at any given temperature is the vapor pressure when relative humidity is 100%. One formula is Tetens' equation from[14] used to find the saturation vapor pressure is: [math]\displaystyle{ p_\text{sat} = 6.1078 \times 10^{\frac{7.5 T}{T + 237.3}} }[/math] where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ p_\text{sat} }[/math], saturation vapor pressure (hPa)

- [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math], temperature (°C)

See vapor pressure of water for other equations.

The partial pressure of dry air [math]\displaystyle{ p_\text{d} }[/math] is found considering partial pressure, resulting in: [math]\displaystyle{ p_\text{d} = p - p_\text{v} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] simply denotes the observed absolute pressure.

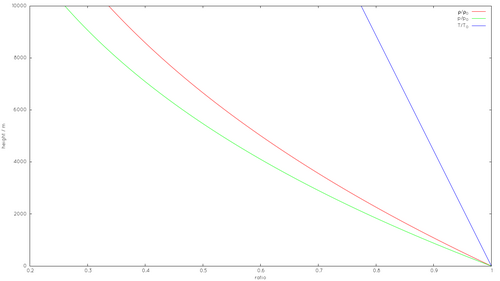

Variation with altitude

Troposphere

To calculate the density of air as a function of altitude, one requires additional parameters. For the troposphere, the lowest part (~10 km) of the atmosphere, they are listed below, along with their values according to the International Standard Atmosphere, using for calculation the universal gas constant instead of the air specific constant:

- [math]\displaystyle{ p_0 }[/math], sea level standard atmospheric pressure, 101325 Pa

- [math]\displaystyle{ T_0 }[/math], sea level standard temperature, 288.15 K

- [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math], earth-surface gravitational acceleration, 9.80665 m/s2

- [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math], temperature lapse rate, 0.0065 K/m

- [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math], ideal (universal) gas constant, 8.31446 J/(mol·K)

- [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math], molar mass of dry air, 0.0289652 kg/mol

Temperature at altitude [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math] meters above sea level is approximated by the following formula (only valid inside the troposphere, no more than ~18 km above Earth's surface (and lower away from Equator)): [math]\displaystyle{ T = T_0 - L h }[/math]

The pressure at altitude [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math] is given by: [math]\displaystyle{ p = p_0 \left(1 - \frac{L h}{T_0}\right)^\frac{g M}{R L} }[/math]

Density can then be calculated according to a molar form of the ideal gas law: [math]\displaystyle{ \rho = \frac{p M}{R T} = \frac{p M}{R T_0 \left(1 - \frac{Lh}{T_0}\right)} = \frac{p_0 M}{R T_0} \left(1 - \frac{L h}{T_0} \right)^{\frac{g M}{R L} - 1} }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math], molar mass

- [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math], ideal gas constant

- [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math], absolute temperature

- [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], absolute pressure

Note that the density close to the ground is [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_0 = \frac{p_0 M}{R T_0} }[/math]

It can be easily verified that the hydrostatic equation holds: [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dp}{dh} = -g\rho . }[/math]

Exponential approximation

As the temperature varies with height inside the troposphere by less than 25%, [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{Lh}{T_0} \lt 0.25 }[/math] and one may approximate: [math]\displaystyle{ \rho = \rho_0 e^{\left(\frac{g M}{R L} - 1\right) \ln \left(1 - \frac{L h}{T_0}\right)} \approx \rho_0 e^{-\left(\frac{g M}{R L} - 1\right)\frac{L h}{T_0}} = \rho_0 e^{-\left(\frac{g M h}{R T_0} - \frac{L h}{T_0}\right)} }[/math]

Thus: [math]\displaystyle{ \rho \approx \rho_0 e^{-h/H_n} }[/math]

Which is identical to the isothermal solution, except that Hn, the height scale of the exponential fall for density (as well as for number density n), is not equal to RT0/gM as one would expect for an isothermal atmosphere, but rather: [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{H_n} = \frac{g M}{R T_0} - \frac{L}{T_0} }[/math]

Which gives Hn = 10.4 km.

Note that for different gasses, the value of Hn differs, according to the molar mass M: It is 10.9 for nitrogen, 9.2 for oxygen and 6.3 for carbon dioxide. The theoretical value for water vapor is 19.6, but due to vapor condensation the water vapor density dependence is highly variable and is not well approximated by this formula.

The pressure can be approximated by another exponent: [math]\displaystyle{ p = p_0 e^{\frac{g M}{R L} \ln \left(1 - \frac{L h}{T_0}\right)} \approx p_0 e^{-\frac{g M}{R L}\frac{L h}{T_0}} = p_0 e^{-\frac{g M h}{R T_0}} }[/math]

Which is identical to the isothermal solution, with the same height scale Hp = RT0/gM. Note that the hydrostatic equation no longer holds for the exponential approximation (unless L is neglected).

Hp is 8.4 km, but for different gasses (measuring their partial pressure), it is again different and depends upon molar mass, giving 8.7 for nitrogen, 7.6 for oxygen and 5.6 for carbon dioxide.

Total content

Further note that since g, Earth's gravitational acceleration, is approximately constant with altitude in the atmosphere, the pressure at height h is proportional to the integral of the density in the column above h, and therefore to the mass in the atmosphere above height h. Therefore the mass fraction of the troposphere out of all the atmosphere is given using the approximated formula for p: [math]\displaystyle{ 1 - \frac{p(h = 11\text{ km})}{p_0} = 1 - \left(\frac{T(11\text{ km})}{T_0} \right)^\frac{g M}{R L} \approx 76\% }[/math]

For nitrogen, it is 75%, while for oxygen this is 79%, and for carbon dioxide, 88%.

Tropopause

Higher than the troposphere, at the tropopause, the temperature is approximately constant with altitude (up to ~20 km) and is 220 K. This means that at this layer L = 0 and T = 220 K, so that the exponential drop is faster, with HTP = 6.3 km for air (6.5 for nitrogen, 5.7 for oxygen and 4.2 for carbon dioxide). Both the pressure and density obey this law, so, denoting the height of the border between the troposphere and the tropopause as U:

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} p &= p(U) e^{-\frac{h - U}{H_\text{TP}}} = p_0 \left(1 - \frac{L U}{T_0}\right)^\frac{g M}{R L} e^{-\frac{h - U}{H_\text{TP}}} \\ \rho &= \rho(U) e^{-\frac{h - U}{H_\text{TP}}} = \rho_0 \left(1 - \frac{L U}{T_0}\right)^{\frac{g M}{R L} - 1} e^{-\frac{h - U}{H_\text{TP}}} \end{align} }[/math]

Composition

See also

- Air

- Atmospheric drag

- Lighter than air

- Density

- Atmosphere of Earth

- International Standard Atmosphere

- U.S. Standard Atmosphere

- NRLMSISE-00

Notes

References

- ↑ Olson, Wayne M. (2000) AFFTC-TIH-99-01, Aircraft Performance Flight

- ↑ ICAO, Manual of the ICAO Standard Atmosphere (extended to 80 kilometres (262 500 feet)), Doc 7488-CD, Third Edition, 1993, ISBN:92-9194-004-6.

- ↑ Grigorie, T.L., Dinca, L., Corcau J-I. and Grigorie, O. (2010) Aircrafts' [sic] Altitude Measurement Using Pressure Information:Barometric Altitude and Density Altitude

- ↑ A., Picard, R.S., Davis, M., Gläser and K., Fujii (CIPM-2007) Revised formula for the density of moist air

- ↑ S. Herrmann, H.-J. Kretzschmar, and D.P. Gatley (2009), ASHRAE RP-1485 Final Report

- ↑ F.R. Martins, R.A. Guarnieri e E.B. Pereira, (2007) O aproveitamento da energia eólica (The wind energy resource).

- ↑ Andrade, R.G., Sediyama, G.C., Batistella, M., Victoria, D.C., da Paz, A.R., Lima, E.P., Nogueira, S.F. (2009) Mapeamento de parâmetros biofísicos e da evapotranspiração no Pantanal usando técnicas de sensoriamento remoto

- ↑ Marshall, John and Plumb, R. Alan (2008), Atmosphere, ocean, and climate dynamics: an introductory text ISBN:978-0-12-558691-7.

- ↑ Pollacco, J. A., and B. P. Mohanty (2012), Uncertainties of Water Fluxes in Soil-Vegetation-Atmosphere Transfer Models: Inverting Surface Soil Moisture and Evapotranspiration Retrieved from Remote Sensing, Vadose Zone Journal, 11(3), doi:10.2136/vzj2011.0167.

- ↑ Shin, Y., B. P. Mohanty, and A.V.M. Ines (2013), Estimating Effective Soil Hydraulic Properties Using Spatially Distributed Soil Moisture and Evapotranspiration, Vadose Zone Journal, 12(3), doi:10.2136/vzj2012.0094.

- ↑ Saito, H., J. Simunek, and B. P. Mohanty (2006), Numerical Analysis of Coupled Water, Vapor, and Heat Transport in the Vadose Zone, Vadose Zone J. 5: 784-800.

- ↑ Perry, R.H. and Chilton, C.H., eds., Chemical Engineers' Handbook, 5th ed., McGraw-Hill, 1973.

- ↑ Shelquist, R (2009) Equations - Air Density and Density Altitude

- ↑ Shelquist, R (2009) Algorithms - Schlatter and Baker

External links

- Conversions of density units ρ by Sengpielaudio

- Air density and density altitude calculations and by Richard Shelquist

- Air density calculations by Sengpielaudio (section under Speed of sound in humid air)

- Air density calculator by Engineering design encyclopedia

- Atmospheric pressure calculator by wolfdynamics

- Air iTools - Air density calculator for mobile by JSyA

- Revised formula for the density of moist air (CIPM-2007) by NIST