Chemistry:Melanophlogite

| Melanophlogite | |

|---|---|

1–3 mm globules of melanophlogite | |

| General | |

| Category | Silicate mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | SiO2 |

| Crystal system | cubic or tetragonal[1][2] |

| Identification | |

| Color | Brown, colorless, light yellow, dark reddish brown |

| Crystal habit | Forms crust-like aggregates on matrix |

| Cleavage | None |

| Fracture | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6.5–7 |

| |re|er}} | Vitreous |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to translucent |

| Specific gravity | 1.99–2.11, average = 2.04 |

| Optical properties | Isotropic, n=1.425–1.457 |

| Other characteristics | Fluorescent, Short UV=weak gray-white, Long UV=gray-white |

| References | [3][4] |

Melanophlogite (MEP) is a rare silicate mineral and a polymorph of silica (SiO2). It has a zeolite-like porous structure which results in relatively low and not well-defined values of its density and refractive index. Melanophlogite often overgrows crystals of sulfur or calcite and typically contains a few percent of organic and sulfur compounds. Darkening of organics in melanophlogite upon heating is a possible origin of its name, which comes from the Greek for "black" and "to be burned".[1][3]

History

Melanophlogite was identified and named by Arnold von Lasaulx in 1876 although G. Alessi had described a very similar mineral as early as in 1827. The mineral had a cubic crystal structure; chemical analysis revealed that it is mainly composed of SiO2, but also contains up to 12% of carbon and sulfur. It was suggested that the decomposition of organic matter (carbon) in the mineral was responsible for its blackening upon heating. All studied samples originated from Sicily, and thus the mineral was called Girghenti, an old name for Agrigento town in Sicily. The name was officially changed to melanophlogite in 1927.[1]

Synthesis and properties

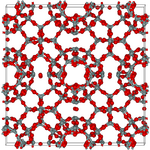

Melanophlogite can be grown synthetically at low temperatures and elevated pressures (e.g. 160 °C and 60 bar). It has a zeolite-like porous structure composed of Si5O10 and Si6O12 rings. Its crystalline symmetry depends on the content of its voids: crystals with spherical guest molecules or atoms (e.g. CH4, Xe, Kr) are cubic and the symmetry lowers to tetragonal for non-spherical guests like tetrahydrofuran or tetrahydrothiophene.[6] Since many molecules form unstable guests, the symmetry of melanophlogite can change between cubic and tetragonal upon mild heating (<100 °C).[6]

Even the cubic melanophlogite often shows anisotropic optical properties. They were attributed not to tetragonal fragments but to the organic film in the mineral which could be removed by low-temperature annealing (~400 °C). Otherwise, melanophlogite is thermally stable and its physical properties do not change upon 20-day annealing at 800 °C, but it converts to cristobalite after heating at temperatures above 900 °C.[1]

Occurrence

Melanophlogite is a rare mineral which usually forms round drops (see infobox) or complex intertwinned overgrowth structures over sulfur or calcite crystals. Rarely, it occurs as individual cubic crystallites a few millimeters in size.[1] It is found in Parma, Torino, Caltanissetta and Livorno provinces of Italy; also in several mines of California in the US, in Crimea (Ukraine) and Pardubice Region (Czech Republic).[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Skinner B.J.; Appleman D.E. (1963). "Melanophlogite, a cubic polymorph of silica". American Mineralogist 48: 854–867. http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM48/AM48_854.pdf.

- ↑ "The crystal structure of low melanophlogite". American Mineralogist 86 (11–12): 1506. 2001. doi:10.2138/am-2001-11-1219. http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/AMS/minerals/Melanophlogite.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Melanophlogite at Webmineral

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Melanophlogite at Mindat

- ↑ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine 85 (3): 291–320. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. Bibcode: 2021MinM...85..291W.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Frank H. Herbstein (2005). Crystalline molecular complexes and compounds: structures and principles, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 364–366. ISBN 0-19-856893-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=G8j3kOWG4GgC&pg=PA365.

External links

- Spectroscopic data on Melanophlogite

- Rosemarie Szostak (1998). Molecular sieves: Principles of Synthesis and Identification. Springer. ISBN 0-7514-0480-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=lteintjA2-MC. - zeolite properties of melanophlogite

|