Tangential and normal components

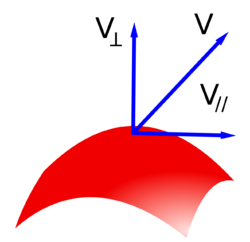

In mathematics, given a vector at a point on a curve, that vector can be decomposed uniquely as a sum of two vectors, one tangent to the curve, called the tangential component of the vector, and another one perpendicular to the curve, called the normal component of the vector. Similarly, a vector at a point on a surface can be broken down the same way.

More generally, given a submanifold N of a manifold M, and a vector in the tangent space to M at a point of N, it can be decomposed into the component tangent to N and the component normal to N.

Formal definition

Surface

More formally, let [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] be a surface, and [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] be a point on the surface. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} }[/math] be a vector at [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. Then one can write uniquely [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} }[/math] as a sum [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} = \mathbf{v}_\parallel + \mathbf{v}_\perp }[/math] where the first vector in the sum is the tangential component and the second one is the normal component. It follows immediately that these two vectors are perpendicular to each other.

To calculate the tangential and normal components, consider a unit normal to the surface, that is, a unit vector [math]\displaystyle{ \hat\mathbf{n} }[/math] perpendicular to [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] at [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. Then, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v}_\perp = \left(\mathbf{v} \cdot \hat\mathbf{n}\right) \hat\mathbf{n} }[/math] and thus [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v}_\parallel = \mathbf{v} - \mathbf{v}_\perp }[/math] where "[math]\displaystyle{ \cdot }[/math]" denotes the dot product. Another formula for the tangential component is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v}_\parallel = -\hat\mathbf{n} \times (\hat\mathbf{n}\times\mathbf{v}), }[/math]

where "[math]\displaystyle{ \times }[/math]" denotes the cross product.

These formulas do not depend on the particular unit normal [math]\displaystyle{ \hat\mathbf{n} }[/math] used (there exist two unit normals to any surface at a given point, pointing in opposite directions, so one of the unit normals is the negative of the other one).

Submanifold

More generally, given a submanifold N of a manifold M and a point [math]\displaystyle{ p \in N }[/math], we get a short exact sequence involving the tangent spaces: [math]\displaystyle{ T_p N \to T_p M \to T_p M / T_p N }[/math] The quotient space [math]\displaystyle{ T_p M / T_p N }[/math] is a generalized space of normal vectors.

If M is a Riemannian manifold, the above sequence splits, and the tangent space of M at p decomposes as a direct sum of the component tangent to N and the component normal to N: [math]\displaystyle{ T_p M = T_p N \oplus N_p N := (T_p N)^\perp }[/math] Thus every tangent vector [math]\displaystyle{ v \in T_p M }[/math] splits as [math]\displaystyle{ v = v_\parallel + v_\perp }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ v_\parallel \in T_p N }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v_\perp \in N_p N := (T_p N)^\perp }[/math].

Computations

Suppose N is given by non-degenerate equations.

If N is given explicitly, via parametric equations (such as a parametric curve), then the derivative gives a spanning set for the tangent bundle (it is a basis if and only if the parametrization is an immersion).

If N is given implicitly (as in the above description of a surface, (or more generally as) a hypersurface) as a level set or intersection of level surfaces for [math]\displaystyle{ g_i }[/math], then the gradients of [math]\displaystyle{ g_i }[/math] span the normal space.

In both cases, we can again compute using the dot product; the cross product is special to 3 dimensions however.

Applications

- Lagrange multipliers: constrained critical points are where the tangential component of the total derivative vanish.

- Surface normal

- Frenet–Serret formulas

- Differential geometry of surfaces § Tangent vectors and normal vectors

References

- Rojansky, Vladimir (1979). Electromagnetic fields and waves. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-63834-0.

- Crowell, Benjamin (2003). Light and Matter. https://www.lightandmatter.com/lm.

|