Flow (mathematics)

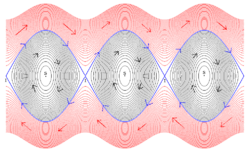

In mathematics, a flow formalizes the idea of the motion of particles in a fluid. Flows are ubiquitous in science, including engineering and physics. The notion of flow is basic to the study of ordinary differential equations. Informally, a flow may be viewed as a continuous motion of points over time. More formally, a flow is a group action of the real numbers on a set.

The idea of a vector flow, that is, the flow determined by a vector field, occurs in the areas of differential topology, Riemannian geometry and Lie groups. Specific examples of vector flows include the geodesic flow, the Hamiltonian flow, the Ricci flow, the mean curvature flow, and Anosov flows. Flows may also be defined for systems of random variables and stochastic processes, and occur in the study of ergodic dynamical systems. The most celebrated of these is perhaps the Bernoulli flow.

Formal definition

A flow on a set X is a group action of the additive group of real numbers on X. More explicitly, a flow is a mapping

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi : X \times \R \to X }[/math]

such that, for all x ∈ X and all real numbers s and t,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \varphi(x,0) = x; \\ & \varphi(\varphi(x,t),s) = \varphi(x,s+t). \end{align} }[/math]

It is customary to write φt(x) instead of φ(x, t), so that the equations above can be expressed as [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi^0 = \text{Id} }[/math] (the identity function) and [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi^s \circ \varphi^t = \varphi^{s+t} }[/math] (group law). Then, for all [math]\displaystyle{ t \isin \R, }[/math] the mapping [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi^t: X \to X }[/math] is a bijection with inverse [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi^{-t}: X \to X. }[/math] This follows from the above definition, and the real parameter t may be taken as a generalized functional power, as in function iteration.

Flows are usually required to be compatible with structures furnished on the set X. In particular, if X is equipped with a topology, then φ is usually required to be continuous. If X is equipped with a differentiable structure, then φ is usually required to be differentiable. In these cases the flow forms a one-parameter group of homeomorphisms and diffeomorphisms, respectively.

In certain situations one might also consider local flows, which are defined only in some subset

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{dom}(\varphi) = \{ (x,t) \ | \ t\in[a_x,b_x], \ a_x\lt 0\lt b_x, \ x\in X \} \subset X\times\mathbb R }[/math]

called the flow domain of φ. This is often the case with the flows of vector fields.

Alternative notations

It is very common in many fields, including engineering, physics and the study of differential equations, to use a notation that makes the flow implicit. Thus, x(t) is written for [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi^t(x_0), }[/math] and one might say that the variable x depends on the time t and the initial condition x = x0. Examples are given below.

In the case of a flow of a vector field V on a smooth manifold X, the flow is often denoted in such a way that its generator is made explicit. For example,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi_V\colon X\times\R\to X; \qquad (x,t)\mapsto\Phi_V^t(x). }[/math]

Orbits

Given x in X, the set [math]\displaystyle{ \{ \varphi(x,t): t \in \R \} }[/math] is called the orbit of x under φ. Informally, it may be regarded as the trajectory of a particle that was initially positioned at x. If the flow is generated by a vector field, then its orbits are the images of its integral curves.

Examples

Algebraic equation

Let [math]\displaystyle{ f: \R \to X }[/math] be a time-dependent trajectory which is a bijective function. Then a flow can be defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi(x,t) = f(t + f^{-1}(x)). }[/math]

Autonomous systems of ordinary differential equations

Let [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol F: \R^n \to \R^n }[/math] be a (time-independent) vector field and [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol x: \R \to \R^n }[/math] the solution of the initial value problem

- [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{\boldsymbol{x}}(t) = \boldsymbol{F}(\boldsymbol{x}(t)), \qquad \boldsymbol{x}(0)=\boldsymbol{x}_0. }[/math]

Then [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi(\boldsymbol x_0,t) = \boldsymbol x(t) }[/math] is the flow of the vector field F. It is a well-defined local flow provided that the vector field [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol F: \R^n \to \R^n }[/math] is Lipschitz-continuous. Then [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi: \R^n \times \R \to \R^n }[/math] is also Lipschitz-continuous wherever defined. In general it may be hard to show that the flow φ is globally defined, but one simple criterion is that the vector field F is compactly supported.

Time-dependent ordinary differential equations

In the case of time-dependent vector fields [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol F: \R^n \times \R \to \R^n }[/math], one denotes [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi^{t,t_0}(\boldsymbol x_0) = \boldsymbol{x}(t+t_0), }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol x: \R \to \R^n }[/math] is the solution of

- [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{\boldsymbol{x}}(t) = \boldsymbol{F}(\boldsymbol{x}(t),t), \qquad \boldsymbol{x}(t_0)=\boldsymbol{x}_0. }[/math]

Then [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi^{t,t_0}(\boldsymbol x_0) }[/math] is the time-dependent flow of F. It is not a "flow" by the definition above, but it can easily be seen as one by rearranging its arguments. Namely, the mapping

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi\colon(\R^n\times\R)\times\R \to \R^n\times\R; \qquad \varphi((\boldsymbol{x}_0, t_0), t)=(\varphi^{t,t_0}(\boldsymbol{x}_0),t+t_0) }[/math]

indeed satisfies the group law for the last variable:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \varphi(\varphi((\boldsymbol{x}_0,t_0),t),s) &= \varphi((\varphi^{t,t_0}(\boldsymbol{x}_0),t+t_0),s) \\ &= (\varphi^{s,t+t_0}(\varphi^{t,t_0}(\boldsymbol{x}_0)),s+t+t_0) \\ &= (\varphi^{s,t+t_0}(\boldsymbol{x}(t+t_0)),s+t+t_0) \\ &= (\boldsymbol{x}(s+t+t_0),s+t+t_0) \\ &= (\varphi^{s+t,t_0}(\boldsymbol{x}_0),s+t+t_0) \\ &= \varphi((\boldsymbol{x}_0,t_0),s+t). \end{align} }[/math]

One can see time-dependent flows of vector fields as special cases of time-independent ones by the following trick. Define

- [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{G}(\boldsymbol{x},t):=(\boldsymbol{F}(\boldsymbol{x},t),1), \qquad \boldsymbol{y}(t) :=(\boldsymbol{x}(t+t_0),t+t_0). }[/math]

Then y(t) is the solution of the "time-independent" initial value problem

- [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{\boldsymbol{y}}(s) = \boldsymbol{G}(\boldsymbol{y}(s)), \qquad \boldsymbol{y}(0)=(\boldsymbol{x}_0,t_0) }[/math]

if and only if x(t) is the solution of the original time-dependent initial value problem. Furthermore, then the mapping φ is exactly the flow of the "time-independent" vector field G.

Flows of vector fields on manifolds

The flows of time-independent and time-dependent vector fields are defined on smooth manifolds exactly as they are defined on the Euclidean space [math]\displaystyle{ \R^n }[/math] and their local behavior is the same. However, the global topological structure of a smooth manifold is strongly manifest in what kind of global vector fields it can support, and flows of vector fields on smooth manifolds are indeed an important tool in differential topology. The bulk of studies in dynamical systems are conducted on smooth manifolds, which are thought of as "parameter spaces" in applications.

Formally: Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M} }[/math] be a differentiable manifold. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{T}_p \mathcal{M} }[/math] denote the tangent space of a point [math]\displaystyle{ p \in \mathcal{M}. }[/math] Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{T}\mathcal{M} }[/math] be the complete tangent manifold; that is, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{T}\mathcal{M} = \cup_{p\in\mathcal{M}}\mathrm{T}_p\mathcal{M}. }[/math] Let [math]\displaystyle{ f : \R\times\mathcal{M} \to \mathrm{T}\mathcal{M} }[/math] be a time-dependent vector field on [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M} }[/math]; that is, f is a smooth map such that for each [math]\displaystyle{ t\in\R }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ p\in\mathcal{M} }[/math], one has [math]\displaystyle{ f(t,p)\in \mathrm{T}_p\mathcal{M}; }[/math] that is, the map [math]\displaystyle{ x\mapsto f(t,x) }[/math] maps each point to an element of its own tangent space. For a suitable interval [math]\displaystyle{ I\subseteq\R }[/math] containing 0, the flow of f is a function [math]\displaystyle{ \phi: I\times\mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M} }[/math] that satisfies [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \phi(0, x_0) &= x_0&\forall x_0\in\mathcal{M} \\ \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t}\Big|_{t=t_0}\phi(t,x_0) &= f(t_0,\phi(t_0,x_0))&\forall x_0\in\mathcal{M},t_0\in I \end{align} }[/math]

Solutions of heat equation

Let Ω be a subdomain (bounded or not) of [math]\displaystyle{ \R^n }[/math] (with n an integer). Denote by Γ its boundary (assumed smooth). Consider the following heat equation on Ω × (0, T), for T > 0,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{rcll} u_t - \Delta u & = & 0 & \mbox{ in } \Omega \times (0,T), \\ u & = & 0 & \mbox{ on } \Gamma \times (0,T), \end{array} }[/math]

with the following initial value condition u(0) = u0 in Ω .

The equation u = 0 on Γ × (0, T) corresponds to the Homogeneous Dirichlet boundary condition. The mathematical setting for this problem can be the semigroup approach. To use this tool, we introduce the unbounded operator ΔD defined on [math]\displaystyle{ L^2(\Omega) }[/math] by its domain

- [math]\displaystyle{ D(\Delta_D) = H^2(\Omega) \cap H_0^1(\Omega) }[/math]

(see the classical Sobolev spaces with [math]\displaystyle{ H^k(\Omega) = W^{k,2}(\Omega) }[/math] and

- [math]\displaystyle{ H_0^1(\Omega) = {\overline{C_0^\infty (\Omega)} } ^{H^1(\Omega)} }[/math]

is the closure of the infinitely differentiable functions with compact support in Ω for the [math]\displaystyle{ H^1(\Omega)- }[/math]norm).

For any [math]\displaystyle{ v \in D(\Delta_D) }[/math], we have

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta_D v = \Delta v = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\partial^2 }{\partial x_i^2} v ~. }[/math]

With this operator, the heat equation becomes [math]\displaystyle{ u'(t) = \Delta_Du(t) }[/math] and u(0) = u0. Thus, the flow corresponding to this equation is (see notations above)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi(u^0,t) = \mbox{e}^{t\Delta_D}u^0 , }[/math]

where exp(tΔD) is the (analytic) semigroup generated by ΔD.

Solutions of wave equation

Again, let Ω be a subdomain (bounded or not) of [math]\displaystyle{ \R^n }[/math] (with n an integer). We denote by Γ its boundary (assumed smooth). Consider the following wave equation on [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega \times (0,T) }[/math] (for T > 0),

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{rcll} u_{tt} - \Delta u & = & 0 & \mbox{ in } \Omega \times (0,T), \\ u & = & 0 & \mbox{ on } \Gamma \times (0,T), \end{array} }[/math]

with the following initial condition u(0) = u1,0 in Ω and [math]\displaystyle{ u_t(0) = u^{2,0} \mbox{ in } \Omega. }[/math]

Using the same semigroup approach as in the case of the Heat Equation above. We write the wave equation as a first order in time partial differential equation by introducing the following unbounded operator,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{A} = \left(\begin{array}{cc} 0 & Id \\ \Delta_D & 0 \end{array}\right) }[/math]

with domain [math]\displaystyle{ D(\mathcal{A}) = H^2(\Omega) \cap H_0^1(\Omega) \times H_0^1(\Omega) }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ H = H^1_0(\Omega) \times L^2(\Omega) }[/math] (the operator ΔD is defined in the previous example).

We introduce the column vectors

- [math]\displaystyle{ U = \left(\begin{array}{c} u^1 \\ u^2 \end{array}\right) }[/math]

(where [math]\displaystyle{ u^1 = u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ u^2 = u_t }[/math]) and

- [math]\displaystyle{ U^0 = \left(\begin{array}{c} u^{1,0} \\ u^{2,0} \end{array} \right). }[/math]

With these notions, the Wave Equation becomes [math]\displaystyle{ U'(t) = \mathcal{A}U(t) }[/math] and U(0) = U0.

Thus, the flow corresponding to this equation is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi(U^0,t) = \mbox{e}^{t\mathcal{A}}U^0 }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \mbox{e}^{t\mathcal{A}} }[/math] is the (unitary) semigroup generated by [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{A}. }[/math]

Bernoulli flow

Ergodic dynamical systems, that is, systems exhibiting randomness, exhibit flows as well. The most celebrated of these is perhaps the Bernoulli flow. The Ornstein isomorphism theorem states that, for any given entropy H, there exists a flow φ(x, t), called the Bernoulli flow, such that the flow at time t = 1, i.e. φ(x, 1), is a Bernoulli shift.

Furthermore, this flow is unique, up to a constant rescaling of time. That is, if ψ(x, t), is another flow with the same entropy, then ψ(x, t) = φ(x, t), for some constant c. The notion of uniqueness and isomorphism here is that of the isomorphism of dynamical systems. Many dynamical systems, including Sinai's billiards and Anosov flows are isomorphic to Bernoulli shifts.

See also

References

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Continuous flow", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=c/c025630

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Measureable flow", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=m/m063190

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Special flow", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=S/s086270

|